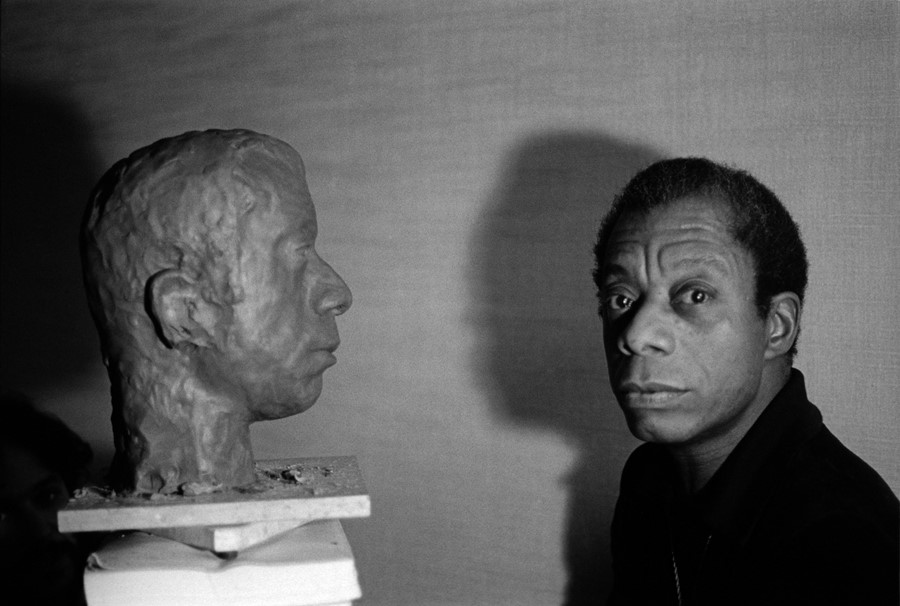

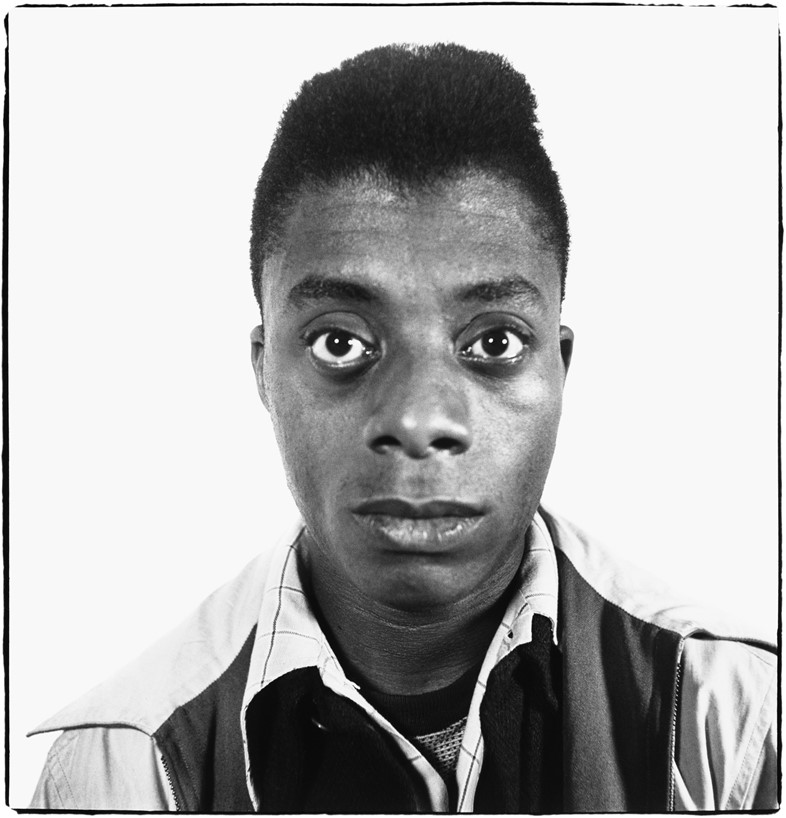

As an exhibition opens in New York focusing on James Baldwin, its curator Hilton Als remembers his encounters with the author’s writing

The work of James Baldwin (1924–1987) speaks not only to his time, but that of our own – calling out abuses of power while painting a heartfelt portrait of those they harm. Yet in becoming a public figure, Baldwin’s fame became a double-edged sword, amplifying the impact of his ideas while simultaneously draining him of his creative resources.

In a new exhibition God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, writer, and curator Hilton Als explores Baldwin’s life as both inspiration and cautionary tale. Featuring the work of Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Richard Avedon, Beauford Delaney, Marlene Dumas, Glenn Ligon, Anthony Barboza, Kara Walker, and James Welling, the exhibition also includes a wealth of archival materials including a vinyl recording of Baldwin singing, Precious Lord, Take My Hand – which Als first heard inside the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine during Baldwin’s funeral.

Here, speaking to AnOther, Als reflects on his relationship with Baldwin, one that came about as Als began his journey just as Baldwin was concluding his.

“My mother worked for a woman named Ruth Gibbs, who was friends with a man named Owen Dodson. Dodson was deacquisitioning some books and I went over there with a shopping cart. We became friends because I think I amused him. I was very anxious to start life as a New York writer. I was only 14, or something like that.

“Owen would tell me stories about writers he had known and he told me all these wonderful stories about James Baldwin. While Owen was directing The Amen Corner, Baldwin and a boyfriend of some sort stayed with him in Washington. Owen, who had a very modest salary as a teacher, said that they ate him out of house and home – so he had to throw them out.

“Owen was deeply funny, and also humanised people, so that when you read a book by Langston Hughes or Countee Cullen, he had a real story about them. I loved how Owen’s stories made the books, the language, and the authors real for me. It was a wonderful moment in my life where all hierarchy was stripped down. The author wasn’t over there but over here sitting next to you, having a cigarette.

“I was attracted to Baldwin’s voice as an essayist and in his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. When I started to read the later novels like Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone or Just Above My Head, I could see something had that gone astray – not only in his voice but he was using fiction as a kind of polemic. There was not any life to the characters, but there was a life to his mind.

“The novels that had gotten tired after The Fire Next Time might have done so because he didn’t preserve any space for himself to think creatively. Baldwin was on the road and public life doesn’t really help the writing life. I felt that he had sacrificed a lot of the integrity, grit, and solitude to be of service to the movement. He is a good example of why it’s important to step away and have those private moments to one’s self. Easy for me to say because he was living at a time when his voice was absolutely crucial to the struggle but it didn’t serve him as a writer.

“The essay, Notes of a Native Son, and the essays on Richard Wright and Ingmar Bergman really resonated with me in terms of the very complicated feelings we have toward fathers and brothers. He was writing about looking for a kind of fraternity or brotherhood. That really struck me as a gay man of colour coming up in the 1980s, when you were losing friends all the time. Those essays really helped me steer the course of my being and helped me understand how I needed to honour him with something that would be as truthful as he had been.”

God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin is at David Zwirner, New York, until February 16, 2019.