Art historian, curator and writer Alayo Akinkugbe is behind the popular Instagram page A Black History of Art, which highlights overlooked Black artists, sitters, curators and thinkers, past and present. In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Black Gazes, Akinkugbe examines a spectrum of Black perspectives from across artistic disciplines and throughout art history, asking: how do Black artists see and respond to the world around them?

Frida Orupabo is the Oslo-based artist known for her distinctive, multilayered collages that combine images from a broad range of digital sources, such as 1980s cinema, colonial archives and eBay. For Orupabo, who is of dual Nigerian and Norwegian heritage, collaging grants the freedom to invent the images that she sought while growing up, which did not exist. She explains that “the only alternative was to make [the images], by cutting away, adding and manipulating”.

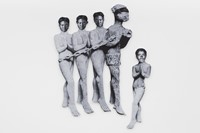

Her current exhibition, Things I saw at night at Modern Art in London features a new series of large-scale, black-and-white collages composed of several layers. Influenced by the happenings of nighttime, each work has a bold, phantom-like presence and they altogether elicit the impression that we – like them – are being looked at. Orupabo often combines the limbs of the animate and inanimate, such as the body of a medieval sculpture from Notre-Dame Cathedral with the face of a Black woman. In doing so, she brings together these subjects, often not associated with each other in reality, to form a new cohesive image in the style of a cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse).

Below, Orupabo speaks to AnOther about the gaze as a symbol of resistance, her artistic process, which involves being “everywhere, collecting everything”, the wondrous archive of her cult Instagram page @nemiepeba, and the inspirations behind her latest show.

Alayo Akinkugbe: Let’s begin with the title of your current exhibition at Modern Art, Things I saw at night. What was the inspiration behind the title?

Frida Orupabo: The collages led me to the title. I started out with one collage Car Ride which in a way influenced the whole show. The car is from the movie Halloween (1988). The original photo is great: it has dark-blue tones, and the shape of the car with Michael Myers’ face in the front seat is amazing.

The atmosphere is nightly and cold. I both love and fear the night; I’m an indoor person. At night I’m in the window peeping out. There are so many things going on at night in the streets: lovers make out or fight, drunk people fall to the ground, newspapers get delivered, scooters get picked up.

For many years I worked as a social worker where we, among other things, did outreach work in the evenings and at night. Working on the show made me remember a lot of things, the stories I was told and the things I saw.

AA: The gaze seems to be a strong presence in this exhibition. What is the significance of looking and being watched in your work?

FO: I guess the gaze has a strong presence in all of my works but I thought of it in a broader sense for Things I saw at night. I am, for the most part, working with images where the subject stares directly back at the spectator. There’s something about working with colonial archives which is so objectifying and so violent; by the use of collage, I am trying to break those images up, to create new and more complex ways of seeing and imagining. A reversed gaze is important because, for me, it represents resistance and power. To look back is to refuse objectification.

AA: What is it about collaging – a process of synthesising images from different bodies, time periods and geographies – that appeals to you?

FO: Collage is the medium that resembles my mind the most: bits and pieces from everywhere, put together to make up a new whole. I think the choice of making collages came very naturally because of the absence I felt growing up and even today. The images I was looking for didn’t – and often still don’t – exist, so the only alternative was to make them by cutting away, adding, and manipulating. It is the best medium for what I want to do.

It’s also an effective way of questioning and recreating narratives and identities; combining images that originally were not meant to stand together. To take apart, leave out and bring together. I think of it as something liberating, something very closely linked to creating and sustaining one’s own self. The layering [of the collages] speaks to complexities and contradictions, the things that make us human.

“There’s something about working with colonial archives which is so objectifying and so violent; by the use of collage I am trying to break those images up, to create new and more complex ways of seeing and imagining” – Frida Orupabo

AA: You start by working with archival images on a screen and then you move to the physical. Can you tell me about the process of moving from the digital archive to producing a physical collage?

FO: I mostly work with digital images. I am online looking at things, anything really, and I download them and put them into folders on my computer.

Often, I encounter problems with resolution when enlarging and printing out different parts of the digital collage. If digital manipulation doesn’t work, I have to find a replacement. I then usually go to eBay where I can search for very specific things, like a shoe, a hand etc.

AA: Your work often draws on images that convey the brutality of colonialism and slavery. What is the motivation behind highlighting these histories of Black suffering?

FO: It’s important. It’s our history and that history still affects and informs our lives, our experiences, the way we think and speak. To work with old archives, particularly the colonial archives, is a way of connecting the past with the here and now. There are no clean breaks, history repeats, and real changes are quite rare.

I am interested in white fantasies about Blackness; how they affect us and our lives but my work is also about other things. I believe, or at least hope, that one finds joy and pleasure in it too. I don’t think much while I work. The thinking often comes after the work is done. I select images based on what moves me. It can be a certain shape I find beautiful, a colour combination, an object, or just something that strikes me.

AA: There is also an almost whimsical quality to certain works in Things I saw at night; do you take influence from the surreal and fantastical?

FO: I am influenced by many things, the images I’ve used come from all over. For instance, for this exhibition there are snaps from vintage horror movies, erotic vintage photos and screenshots from films, photos from colonial archives, stuff from eBay; clothes, miscellaneous objects and more. I’m everywhere, collecting everything.

AA: @nemiepeba, your Instagram page is a wonderfully curated archive in itself, which has garnered a wide audience. I have enjoyed following it closely for three years. What were the origins of this archive?

FO: I started it out of a need to find a space where I could post stuff: found images, films, text and my own digital collages anonymously. Most of the followers, very few at the beginning, were strangers. It made the platform safe and I didn’t feel too watched.

Instagram used to be a platform where you also could see what other accounts liked and commented on, so it was – more then, than now – a resource to find material for my collages. It was also a place where I could play around with images. The grids made it possible to make narratives that were changing with every new image that I put out. It became a diary, an archive storing films, text and images that I wanted to remember and come back to, but yes, at the same time it became a carefully curated entity in itself. It is still all of those things.

Things I saw at night by Frida Orupabo is on show at Modern Art in London until May 20, 2023.