As A Hard Man is Good to Find! opens at The Photographers’ Gallery, curator Alistair O’Neill talks about the covert visual culture of making and sharing erotic images among gay men from the 1930s until the 1990s

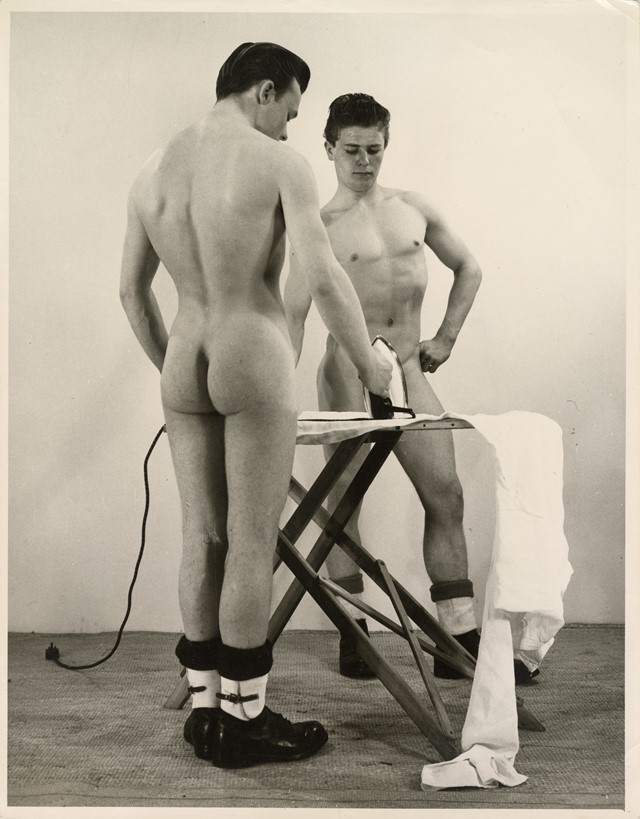

It’s widely accepted that the jockstrap became a symbol of queer culture in 1950s America – popularised by Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial magazine, which was first published in 1951. However in Keith Vaughan’s early photographs, shot at Highgate Men’s Pond in 1933, a counter-narrative emerges, as at least one of his group models a similarly revealing-yet-concealing piece of underwear. “This challenges that history in a really interesting way,” asserts the curator and Central Saint Martins professor Alistair O’Neill, whose new show, A Hard Man is Good to Find! at The Photographers’ Gallery, will exhibit Vaughan’s album of swimmers and sunbathers for the first time.

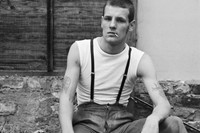

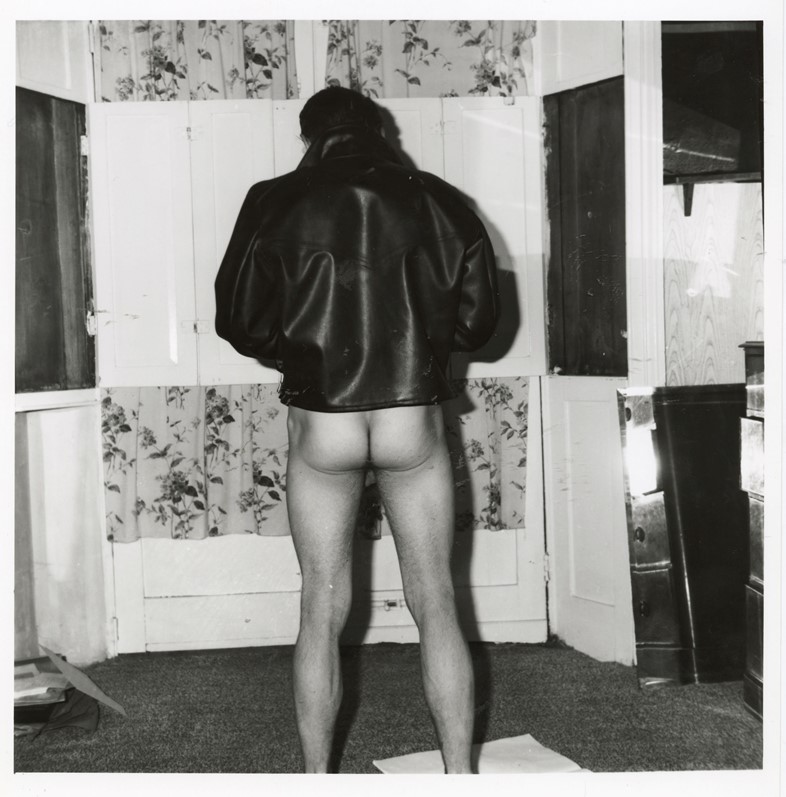

“He was 21, printing the photographs in his bedroom,” continues O’Neill. “They could have been used as incriminating evidence against him – he could have been imprisoned for taking those images – so it’s amazing this body of work survived.” Comprised of over 100 images made between the 1930s and 1990s, much of the work that features in the show was informed by similarly obstructive legalities, made after the 1955 Wolfenden Report and the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, which partially decriminalised gay sexual activity, but against the backdrop of the 1857 Obscene Publications Act, which made the making and sharing of images depicting homosexuality a criminal offence. Effectively initiating a covert visual culture among gay men, the respective laws shaped a community that married invisible practices with striking body types.

O’Neill’s research began in 2002, when he curated an anniversary show for the Queer Nation club night, celebrating gay clubbing since the Second World War (launched in the early 90s, the night borrowed its moniker from a splinter group of ACT UP). “It made me realise that there were pockets [of surviving history], but a lot of it had not survived through forms of queer erasure – subjects concerned about things being turned into evidence, or cultural institutions misinterpreting that kind of material,” he says. Subsequently, around 80 per cent of the work on show has been loaned from private collectors. “Which is quite unusual and really important – without them a lot of this material would not have survived. Even when collecting, they went to museums, which all said no. Thankfully the tide has turned, and exhibitions like Queer British Art at Tate Britain have shown the importance of these practitioners and their work.”

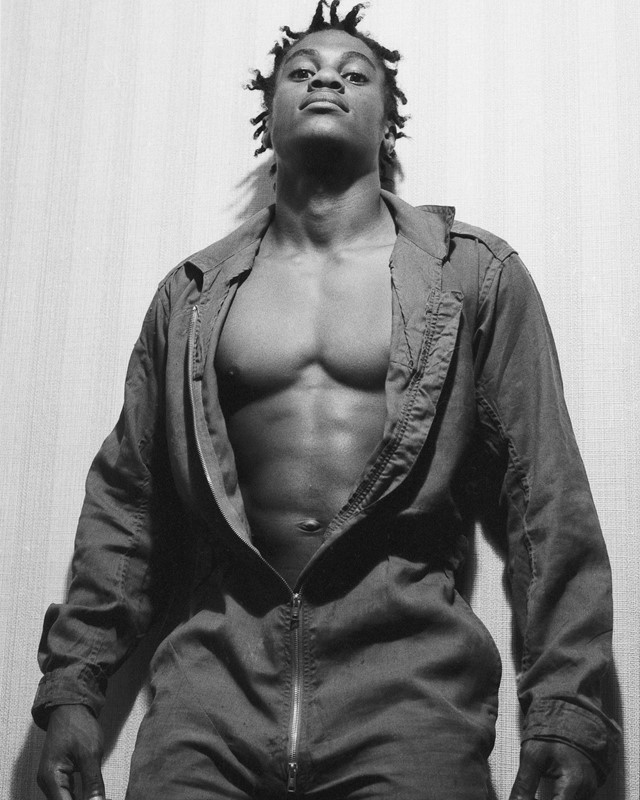

Riffing on the beefcake aesthetics of Mizer’s Athletic Model Guild, the show foregrounds work by Cecil Beaton, Guy Burch and Ajamu X, featuring anonymous pictures of the Portobello Boys from the 50s, a portrait of Monotosh Roy, the first Asian man to win Mr Universe (in 1951), and street portraits made around Euston in the 80s. While sourced from across the UK, London is very much the nucleus, with key areas for men seeking men to photograph mapped across the boroughs. “London was really the centre of production for this kind of imagery,” observes O’Neill. “There’s something about large-scale, metropolitan cities facilitating those same-sex encounters – it’s an important part of how queer culture manifests, in large cities as opposed to more remote, smaller areas.”

“The project is trying to develop a framework for looking at this kind of imagery that doesn’t position artists on one side of the room and physique photographers on the other,” he continues, alluding to traditional artistic groupings. “It’s putting them all together, so different characters rub up against each other in ways that you might not have expected.” Despite echoing a quote attributed to Mae West, the show’s title was actually lifted from a catalogue sheet list of photographer John S Barrington. “I just thought it was funny; it’s provocative, risqué. I was also trying to galvanise this idea that physique photography represents this ideal of masculinity – that is a hard body,” notes the curator.

Culminating in the last decade before social media and online dating, A Hard Man is Good to Find! presents a marker of specific visual trends in gay spaces. “By the end of the 20th century, physique photography was replaced by pornography, so it’s about that, but also the legacy of Aids and how it decimated those communities,” says O’Neill. “It’s both really, and the British story is not well known at all – there are compendiums of Physique Pictorial – but this deserves the time and space.” Spread across the capital over 60 years, what O’Neill hadn’t anticipated was the organic thread that runs through the show. “Everything is amazingly interconnected in ways I never had anticipated. There’s a photograph of the artist Patrick Procktor taken by Cecil Beaton in 1967. In the background there are two life models, then two men on the other side of Patrick’s shoulder – one of the men is actually Vaughan. I didn’t know he bore any relationship to Procktor, so that was amazing.”

A Hard Man is Good to Find! is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London until 11 June 2023.