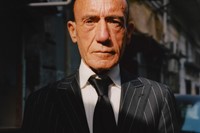

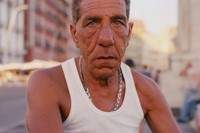

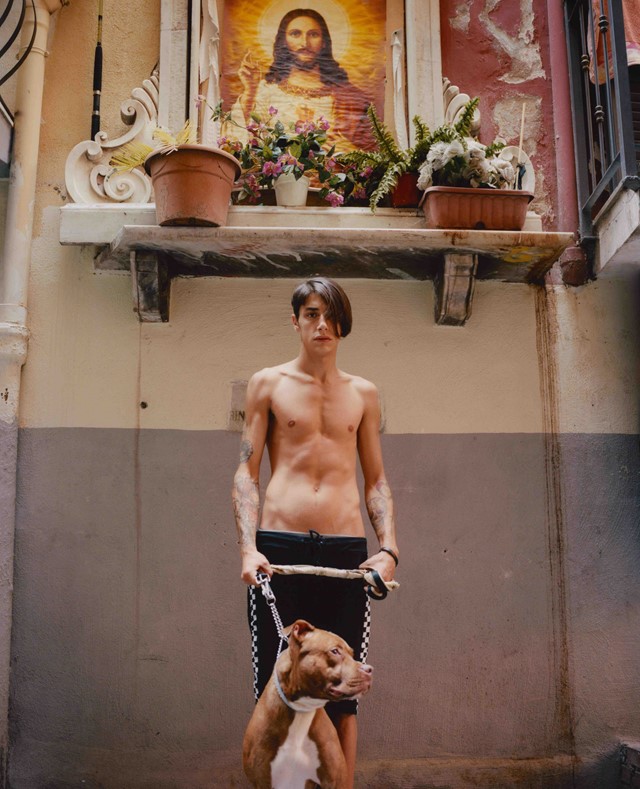

“The people are so welcoming, friendly, theatrical, and everything about them is unique – the way they talk, the way they dress,” says Sam Gregg of his Neapolitan subjects

In Paolo Sorrentino’s autobiographical feature, The Hand of God, Naples is the supporting character to adolescent grief. On Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations (season seven, episode 11), the city serves as a remedy to the chef’s nostalgia-induced red sauce trail. For British photographer Sam Gregg, it is a source of rich inspiration, charged with scenes that run the gamut from the warmly striking to the wonderfully tender.

Gregg’s initial connection to Italy was born out of childhood trips to the North, but when he visited Naples for the first time in 2014, it was as if something clicked. “I’ve always had this fascination,” he explains over Zoom, “and when I went I fell in love with it immediately.” In 2015 he moved there full time, teaching English in the mornings and evenings and shooting in the in-between hours. Since returning to London as a consequence of Brexit, he’s continued shooting in the city, last visiting in the summer of 2020: these pictures are the most recent iteration of a project that reflects the “tunnel vision” he describes having for the past nine years.

“I started photography relatively late,” says Gregg, “not really late – Letizia Battaglia, one of my idols, started taking photographs when she was 36 – I was 23 or 24 and tired of my dead-end job in TV. I remember being surrounded by deeply uncreative people that happened to be in positions of power, and I thought if they can do it, I can. So I picked up a camera.” In an earlier project, he photographed residents of the Klong Toey slum in Bangkok, where he was then based for work, and his subsequent pictures have been informed by a similar preoccupation with outliers and correcting narratives.

With See Naples and Die – a riff on Goethe’s Italian Journey (1786) and a tongue-in-cheek reference to Naples’s rough reputation – Gregg moved around the city, building relationships with the community and shooting portraits, predominantly in the historical centre. “The way I work is very relaxed, I don’t have specific thematics in mind. I wander and follow my instincts, it’s very loose,” he tells AnOther. “I’m just showing the humanity of Naples. Not trying to sugarcoat things, I’m showing things how they are.”

“Neapolitans are somewhat ostracised by the rest of Italy,” he continues. “Many don’t consider themselves Italians, it’s like a breakaway state – they speak their own dialect. You see it in the news, the way they’re portrayed, it’s totally false. Obviously, there are very real socio-economic issues, but it’s not the place it is portrayed to be.” Over the years Gregg has observed an economic and cultural shift in the city, as it moves away from tired stereotypes, and by extension, its image. “Locals have finally harnessed the idea of tourism, but with it you’re losing something intangible,” he notes.

Despite the changes, living in Naples fills him with absolute joy, he says. “It’s the small things. You walk down the street and someone’s grandma will just start talking to you. You feel part of this big, dysfunctional family; that’s what I love about it, the community. The people are so welcoming, friendly, theatrical, and everything about them is unique – the way they talk, the way they dress. That’s why photographing there is such a joy – I take photographs because I enjoy the experience of interacting with people.” He’s quick to point out, however, that the relationship does have complications, and while shooting is fun, genuine intentions matter.

“It’s hard to talk about Naples as a foreigner. I have the chance to escape, so I’m in a position of privilege compared to those born into the system,” acknowledges Gregg, recognising that his unique position as a photographer is a point of potential contention. “I understand. Neapolitans feel as if their culture is being exploited – I can’t tell you how many photographers are shooting there now, compared to ten years ago – but I’m happy the city is prospering. It’s irrelevant that I don’t get the same photographs now.” With this in mind, the response from Neapolitans to his work has been largely positive. “Overwhelmingly, and that’s all I care about. I’ve done everything I can to understand the culture, appreciate it and learn, and I believe that they can see that in the images.”