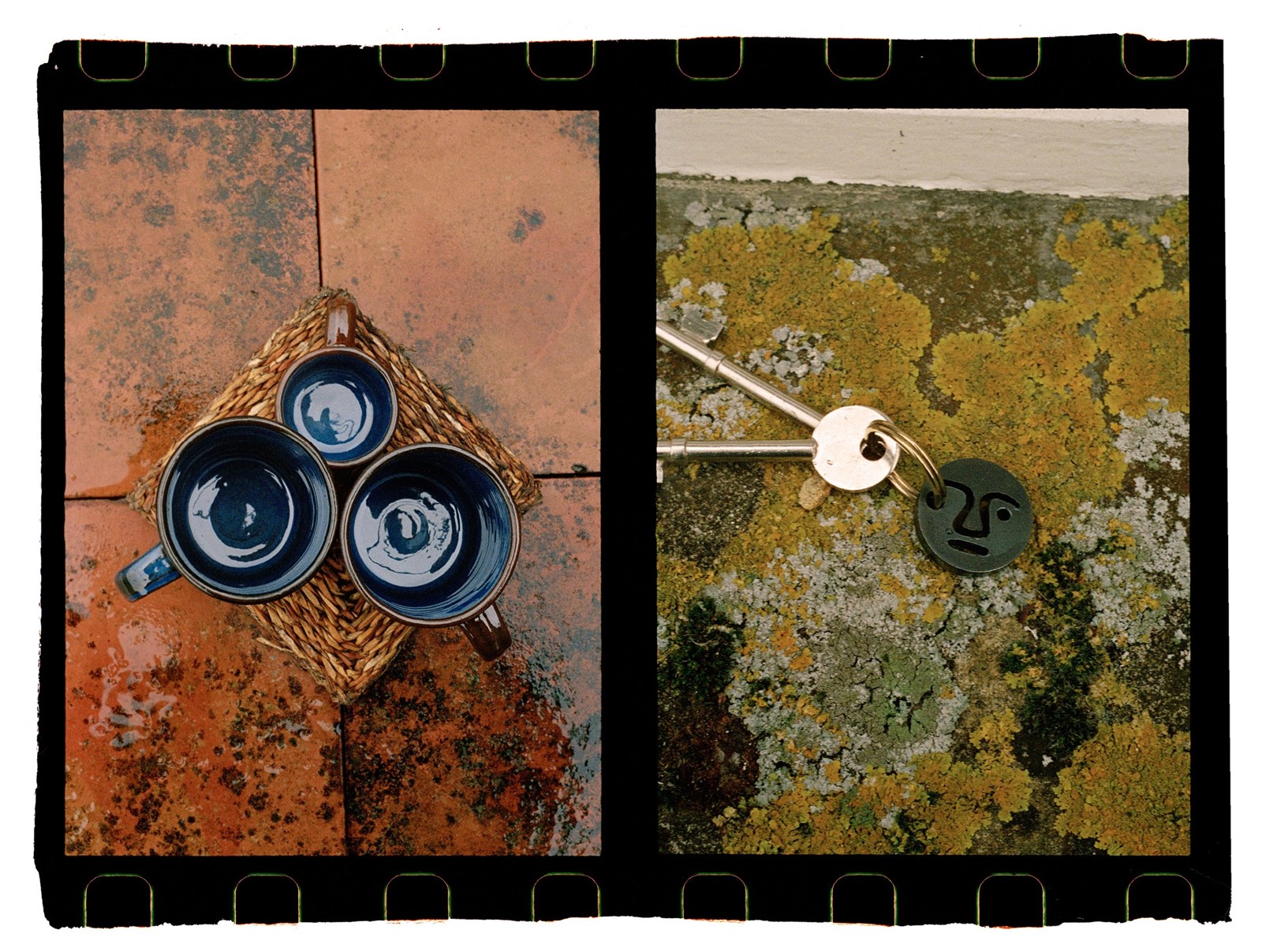

While Tender denim is named after the coal truck on a steam train, thanks to founder William Kroll’s enthusiasm for Victorian engineering, it’s an apt epithet for his business too. After driving through torrential rain to Stroud for the interview (the global business has no London base), I arrive expecting a studio or a workshop, but instead pull up to a green front door on a quiet residential street. A bespectacled man wearing wide, unbleached cotton trousers and a dark blanket-cloth shirt opens the door and beams, before ushering me into a long open-plan space with bright orange Formica kitchen, cosy sitting room and dining room. Salt dough cut into festive shapes for making Christmas tree decorations covers the table and Deborah, Kroll’s wife (a dancer by profession) comes downstairs with their young baby to say hi. Kroll has brewed coffee in anticipation of my arrival, in a jug he designed with a potter his granny introduced him to and sold via Tender's eccentric online Trestle Shop. He attentively refills my cup as we chat and I have to remind myself that I’m here to work, not to spend time with old friends.

Before the interview, Kroll leads me through the grizzly weather in their back garden to a tiny pattern cutting studio-cum-stockroom, which just about fits the cutting table. A selvedge denim curtain protects shelves from dust, and Kroll guides me through his products and brands: from the core Tender denim label launched in 2009, now with 70 stockists worldwide and two seasonal releases a year, to 1970s-style workwear denim brand Whopper (launching in Spring 2017) and a secretive, mid-century fabric project in development. There are boxes of petite yet chunky watches under the name GS/TP (General Service/Trade Pattern) developed from military issue designs; brightly coloured socks, ceramics and garments from Sleeper, Kroll’s simpler collection based on British rail uniforms and produced in Japan. When it comes to design and manufacture, Kroll is an irrepressible polymath. Astonishingly, given the number of stockists and the fact that Tender’s sales are ten times what they were in 2009, Kroll is a one-man band, not counting his manufacturing partners.

After graduating from Central St Martins where he studied menswear, Kroll worked for Japanese denim brand Evisu as a designer. He was often in Japan, and he made the most of his time there, enrolling in night school to learn the language so that a master indigo dyer could teach him his craft. He reached a point where he needed to launch on his own to realise his denim ambitions. “I started to imagine what a pair of jeans would be if they were mine. I like steam trains and I like a Victorian approach to engineering – as with Isambard Kingdom Brunel's idea of invention and a new technology that is still understandable and transparent – so that you feel if given enough time and long bits of steel you could build a suspension bridge or a steam engine or an early bicycle." He continues, “I’m not reactionary, but I just like that simple approach to things. Finally, after saving up a little and painstakingly developing the pair of homemade jeans that would become the Tender prototype in dialogue with the contributors to Superfuture’s ‘suptertalk’ denim forum, Kroll set out on his own, with no investors.

The aesthetics of Tender have been shaped through Kroll’s deconstructive approach to design and manufacture. He is fascinated by how workwear evolved in response to the emerging forms of physical labour in Britain and American in the 19th century: “I'm really interested in the way British rail workers wore versions of tailored suits that then became rough over time, with reinforced panels under pockets; because that’s where they got worn in the most. And then you had American gold diggers who wore suit trousers made out of canvas cloth, because that would last better than other fabrics. There are definite parallel evolutions between these two forms of dress."

But Kroll does not make collections of nostalgic pastiche that appropriates old for old’s sake: “It’s nice to conduct research and dig up old details; but rather than just saying ‘oh, here is a pocket in a certain shape that we haven’t seen in a hundred years – let’s put it somewhere!’, it’s interesting to consider why that particular pocket has been formed in such a way; what people were actually using it for.” As he explains, “today, we tend to walk around with hands in pockets, rather than using them to carry tools, so, my thought processes are focused on how we can apply the same functional attitude to modern day useage. I usually don’t think of things in visual terms; but, ‘how will it look if I make it like that?’ If you get the sweet spot, it’s interesting on all levels.”

Tender denim is made in Leicester by a couple who were on the verge of winding down their old-fashioned factory before Kroll asked if they would make clothes for him. A few seasons ago, sales grew to the extent that Tender became the factory’s sole customer. It’s a relationship that works well for both sides: “I thought about manufacturing in Japan, but was very lucky to be introduced to the factory through a friend of a friend. It’s lovely working with them; at the moment we’re halfway through Spring/Summer 2017 production, but I took patterns in on Wednesday and they just dropped everything to make samples up for Autumn/Winter 2017 instead. They're very accommodating.” He continues, “It’s nice to be working with people who aren’t making for other brands, because there are no preconceptions about how to craft garments. Often my clothes are made on the wrong machine: typically shirts should be made on fine gauge machines, but mine are made on machines that should make canvas bags!”

Kroll posts every order out to stores or individual customers himself, and often enters into personal correspondence with faithful followers who buy from his unconventional, labyrinthine online stores, that defy all rules of contemporary web design: “I write a little note that gets sent out with each piece and it says ‘you are its Tender and how it turns out is up to you’. It’s following the idea that while the product is the end of the manufacturing process, it’s just the beginning of the wearing process; that the point at which you buy something is the middle of its life and it will get much more special over time. The point at which it becomes perfect is when it’s furthest away from the moment I sell it.”

Paradoxically then, despite the fact that Tender is the epitome of a slow denim brand – with indigo dying, British handwoven fabrics, two people working in the factory and Kroll in charge of everything else – his hands-on model is dynamic and responsive, and has scaled smoothly upwards as his company has grown, with no lack of commercial success. After his first few seasons when owner of British brand Folk, Cathal McAteer, let Kroll use his showroom and introduced him to shops, Tender has accrued dozens more stockists (now, around 70 including the ones he has retained throughout the life of the brand), undoubtedly an incredible achievement. Yet, Kroll has also guarded himself against one-season wonders; refusing requests from several major department stores to feature his denim on their shop floors.

Kroll often gets asked by students at Central St. Martins, where he teaches for advice on how to run a successful business, and rather like the design and make of his jeans, his formula for commercial longevity is old-fashioned: “I’ve always delivered early or on time and I’ve never cancelled anything; also, I’ve never had investors. I’m a left wing-liberal person and this sounds like a hardnosed, freemarket thing to say, but I think it’s important being able to run a business by being able to sell things that people want to buy, to pay suppliers on time, also expecting and hoping that you will be paid on time too. I am very lucky that I work on my own and I have no one to answer to. I am designing for people who are actually going to wear my clothes.”

After the interview is over, William and Deborah insist I stay to eat before driving back to London. While he cooks (delicious Singapore-style noodles of which I had three helpings) their daughter sits on my lap and asks that I read her a story. It’s the first time I’ve read Dr. Seuss out loud during an interview, and probably the last, but it seemed to epitomise the way that Kroll conducts his business: tenderly.