We remember the indomitable Paris-based poet and publisher, whose fierce support of the Harlem Renaissance saw her become one of the most vocal anti-fascists of her time

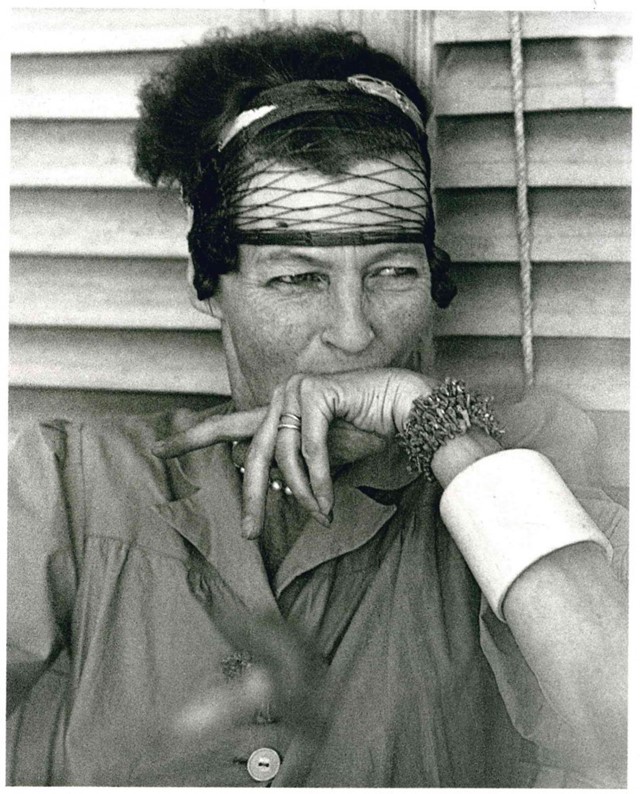

“Never in her life, I believe, was she frightened of anything,” said the critic Raymond Mortimer – and indeed, the life of Nancy Cunard, socialite-cum-activist, poet, journalist, and intellectual, was defined by a profound disregard for fear. Which is to say, the kind of fear that typified the social landscape around her: that of breaking convention, or of the irregular and the unfamiliar. If Cunard was frightened of anything, it was mediocrity.

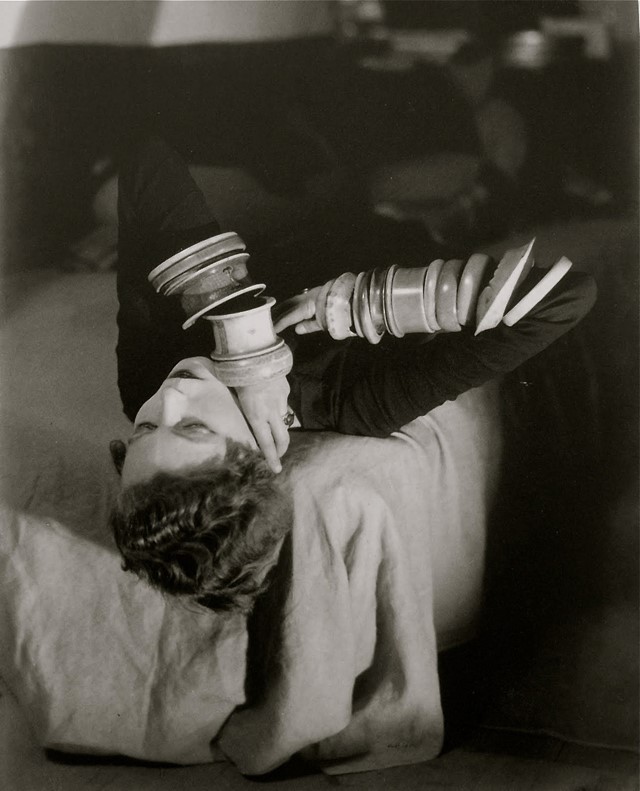

Fictionalised and mythologised by the avant-garde, she outdid them in their very avant-gardeness. She was known to party with a certain zeal, yet she protested and campaigned with even greater vigour. She dressed as strikingly as she wrote, and her condemnation of a society which seemed hellbent on condemning her first was her lifetime’s work.

Defining Features

Nancy was born in 1896 to the titled Cunard Line shipping magnate, her father, and famed American hostess Maud Cunard, her mother. Well-connected and wealthy, the young Cunard was set to make a splash in polite society; it was clear the role of the innocuous debutante was not for her, nor even that of the rebellious heiress. The poet started out as the archetype of the wayward jazz-age socialite, but she quickly went on to break the mould, transcending all of the attached clichés.

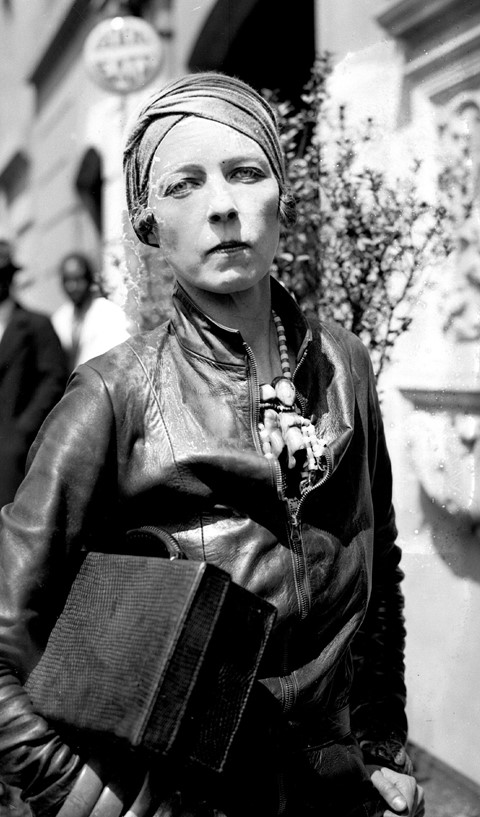

Cunard's style alone provoked outrage. The sight of theatrical kohl-ringed eyes, cropped hair, leather jackets and hitherto unseen jewellery issued shudders of confusion and genuine shock into the hearts of the upper-class. Journalists and critics lambasted her appearance, but she simultaneously served as beacon to a large cast of photographers, painters and sculptors, all drawn in by the irresistible pull of something unknown.

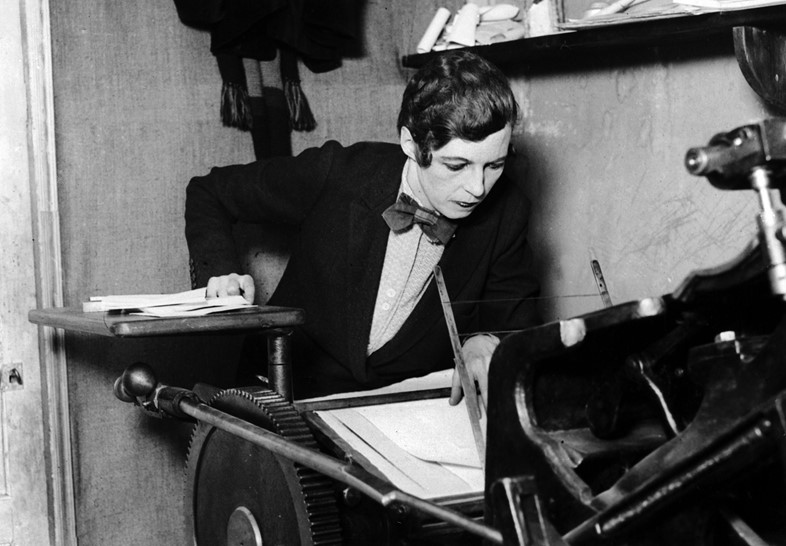

Cunard was to break new intellectual ground in Paris, where she set up The Hours Press, publishing and facilitating a glittering round of modernist writing, championing the likes of Samuel Beckett. She became the basis of several characters for writers, including Aldous Huxley and Evelyn Waugh. Michael Arlen notoriously fictionalised her as Iris Storm in The Green Hat, where he describes her as “the first Englishwoman I ever saw, with shingled hair”.

One aspect of Cunard's character that is often overlooked, however, is her talent for poetry. Where other modernist poets shared experimental techniques, styles and ideas, as a woman, Cunard was accused of imitating the likes of T.S. Eliot, in spite of the fact that, as history proves, he was so directly influenced by her.

Seminal Moments

Perhaps one of the most controversial relationships of Cunard’s life (and of the era) was her involvement with the black American musician Henry Crowder – a relationship which left the tabloids, and her mother, scandalised. The viscous reaction, both from family and the media, resulted in The Black Man and The White Ladyship, an essay by Cunard which passionately condemned both her mother’s racism and racism at large.

Cunard also famously published the brilliant but much-neglected writers of the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Thurston, culminating in Negro, described by Cunard as “an anthology for the recording of the struggles and achievements, the persecutions and the revolts against them, of the Negro peoples”.

She is an AnOther Woman Because...

Undermined and misportrayed throughout her life until after death in 1965, Cunard still remains a relatively marginal figure, but she went on to become one of the most vocal anti-fascists of her time. Undoubtedly gender comes into play in this underrepresentation: lesser talented men, whether poets, activists, journalists or intellectuals, have made it into the canon.

“To be in the presence of Nancy was more like coming to grips with a force of nature...” said the writer Solita Solano. “It was impossible for her to work quietly for the rights of man; Nancy functioned best in a state of fury in which, in order to defend, she attacked every windmill in a landscape of windmills.”