We remember the dancing pioneer whose poetic vision left a permanent mark on the worlds of dance and costume alike

The late Pina Bausch’s light is one that will never go out: even now, seven years after her death in 2009, the German choreographer’s legacy continues to illuminate audiences from Great Britain to Brooklyn, comprising her emotionally raw, humanistic approach to movement, her ability to seamlessly meld theatre and multimedia, and her commitment to turning gender conventions on their head. From her days as a student at the Folkwang School under the tutelage of Expressionistic modern dancer Kurt Jooss, to the height of her career as head of the Tanztheater Wuppertal, which catalysed an international choreographic revolution, Bausch retained her sense of perpetual wonder when it came to harnessing movement’s power to tell stories and challenge preconceptions. Today, AnOther honors the memory of a woman who committed her life to respecting her singular vision – and sharing it with the world.

Defining Features

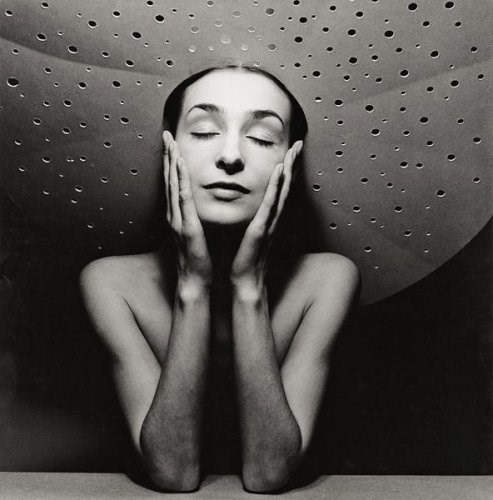

Stare into Pina Bausch’s eyes for a moment, if only in a photograph, and you will immediately find yourself struck by their knowing power. Whether leading a rehearsal or taking center stage, Bausch exuded a pared down simplicity through what she wore, which lay in striking contrast to her colorful imagination. Most of the images that remain of Bausch show her in motion, donning her signature monochrome ensembles: sheer cream slip dresses, elegant black leotards, or on occasion, an oversized trench coat. She typically wore her hair pulled back into a neat ponytail, all the better to transition from rehearsal studio to stage. When not teaching or performing, a cigarette often burned between her fingers.

When it came to her on-stage sartorial aesthetic, Bausch drew inspiration from the street; as AnOther’s Daisy Woodward noted a few years back in a piece about Bausch’s costumes, “Tanztheater costumes are interesting in that they present the dancers primarily as normal people – in dresses, suits, high heels and everyday shoes – as opposed to performers in traditional leotards and ballet shoes.” At the helm of her distinctively quotidian costume designs was Marion Cito, who assumed the role in 1980. Over the course of their longtime collaboration, Cito and Bausch began to speak the same aesthetic language. The costumes that accompanied Bausch’s approach to dance theatre required flexibility, both in terms of ease of movement and breadth of interpretation. For Bausch, the clothes her dancers wore served a far more symbolic role than simply fabric on bodies: they spoke to and embodied human desire, deeply embedded gender norms, and the mysteries of our subconscious minds.

Seminal Moments

As a child in 1940s Germany, Philippine Bausch (nicknamed Pina), often helped out her parents in the restaurant they ran. So began her earliest character studies and her keen interest in the art of observation. When she turned 14, Bausch began her training at the Folkwang School in Essen, where her teacher, Kurt Jooss, encouraged her to move beyond the strict rules of classical ballet and seek creative expression from a wide range of art forms and styles; the seeds were thus planted for Bausch’s open-minded approach to dance making.

Upon receiving a prestigious grant from the German Academic Exchange Service, or DAAD, Bausch packed her bags and headed for Manhattan, where she spent a year at the Julliard School of Music as a pupil under some of the era’s dance legends, including Antony Tudor, José Limón, and Martha Graham company dancers Alfredo Corvino and Margret Craske. Bausch soaked up the city’s vast cultural offerings and, over time, any boundary that once existed in her mind between high and low art or ‘serious’ and ‘popular’ music utterly dissipated – a development which would significantly shape her choreography to come.

Upon moving back to Essen at the urgings of Jooss, Bausch at last began to choreograph independently, and in 1973, Director of the Wuppertal theatres Arno Wüstenhöfer appointed her head of the Tanztheater Wuppertal. From that point forward, it became difficult to keep count of her contributions: she created the first dance operas (including 1975’s striking Orpheus and Eurydice), infused her works with popular music (1974’s I’ll Do You In”) and old German folk songs alike (1977’s Come Dance with Me), and, in 1975, staged what has since become her milestone production: her choreography for Igor Stravinsky's electric Le Sacre du Printemps.

Bausch’s works served up a potent cocktail of drama and humour. In the worlds she established on stage, realism and surrealism did not exist in contradiction but rather as essential foils to one another. Along with challenging gender-role conventions, whether through costuming or mannerisms, her sense of playfulness never took away from her politically relevant statements. Not surprisingly, Bausch’s emotionally honest approach to choreography has inspired countless works by younger dance makers, from William Forsythe to Lloyd Newson of DV8, and even film directors like Pedro Almodóvar. Bausch received innumerable accolades, including the New York Bessie Award in 1984, Japan's Praemium Imperiale in 1999, and the Golden Mask in Moscow in 2005. In 1997, 12 years before her death in June 2009, the German government honoured her with the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

She’s AnOther Woman Because…

Today, the Tanztheater Wuppertal carries on in their beloved leader’s absence. In 2014, they returned to New York’s Brooklyn Academy of Music to mark the 30th anniversary of the New York debut of Kontakthof. In all its deliciously awkward, delightfully relatable scenes of love, lust, and loss between the sexes, it felt as fresh and relevant as ever – and in 2015, took part in AnOther Magazine's seminal MOVEment project in collaboration with Miuccia Prada. Given Bausch’s fluidity between theatrical and pedestrian movement styles, her work speaks to the ways in which we might all exist in a perpetual state of preparation – waiting for our individual and collective performances under the spotlight of the world’s stage. In Pina Bausch's own words, dance theatre was not about mere “provocation,” but rather about establishing “a space where we can encounter each other.” For inspiring all those who encountered her work to dream, to dissent from societal norms, and of course, to dance with abandon, Bausch has undoubtedly earned her spot as an AnOther Woman.