It's been 25 years since Nirvana's 'Nevermind' changed the face of music, fashion and pop culture as we know it – to celebrate, we consider the impact of Cobain's gender-subversive style

“Nirvana’s influence on fashion and style might be even more enduring than its sonic output,” suggested The Hollywood Reporter on the eve of the band’s induction into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame. “Singer Kurt Cobain’s holey grandpa cardigans, ripped jeans, striped ’70s T-shirts and bleached ravaged locks – along with Jackie O-style sunglasses, feather boas and cheetah-print coats – were appropriated by every disaffected youth in existence in the early 1990s.” Never having been a particular fan of their albums, it’s true that my first encounter of note was sartorial: viewed from the suburbs, their FLOWER SNIFFIN’ KITTY PETTIN’ BABY KISSIN’ CORPORATE ROCK WHORE T-shirt looked, to a preteen girl, like subversion. However, later I learned that the group’s real subversiveness came from their leftist political stances and liberal, pro-feminist thinking as much as their slogans.

During an age where rape culture and misogyny is still disarmingly prevalent – if you need proof, see Brock Turner’s father calling the rape his son committed earlier this year “twenty minutes of action” — it’s galling to note that it’s been a full twenty-five years since Kurt Cobain was advocating teaching young men not to rape and dissembling gender binaries; as he once explained, “The problem with groups who deal with rape is that they try to educate women about how to defend themselves. What really needs to be done is teaching men not to rape. Go to the source and start there”. But Cobain’s influence on equality extended beyond the explicitly political, and well into the domain of fashion.

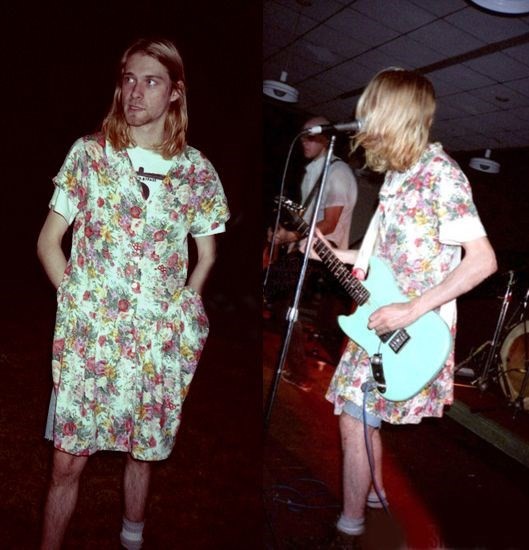

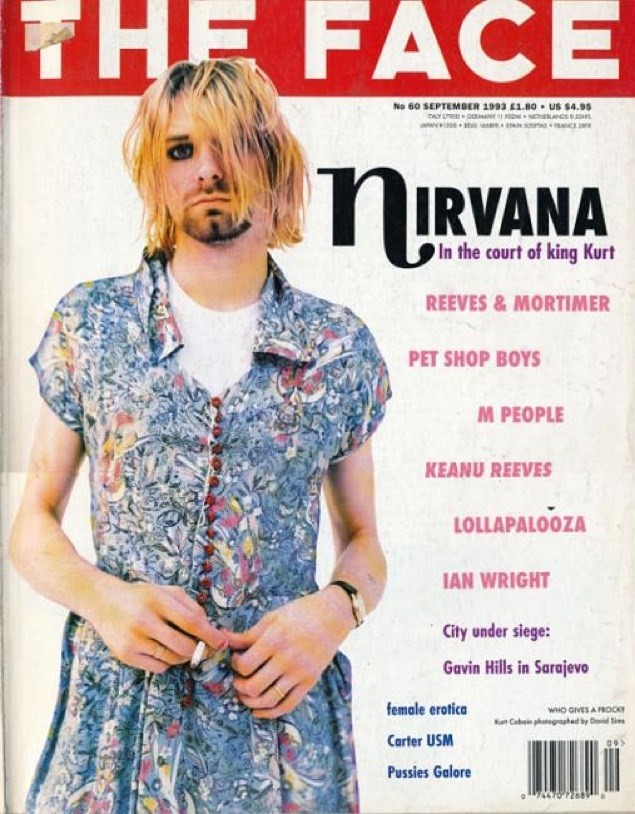

Like Iggy Pop, who once argued that “dressing like a woman” could never be shameful because, put simply, he saw no shame in the actual fact of being a woman, Cobain was man enough to sometimes be feminine. Men, he told a journalist, should wear make-up “only if it’s applied in a real gaudy fashion and makes you look like a TV evangelist’s wife” — on the cover of 1993’s September issue of The Face, he wore a buttoned-up tea dress and chipped red nail polish; after all, as he once told Melody Maker, “there’s nothing more comfortable than a cosy flower pattern.” Decades before the media went wild over Ryan Gosling for saying that women were better than men, Cobain called them the future — “the only future” — of rock and roll; which, in my view, is cooler by half than just “better.” Topping the list: he married Courtney Love.

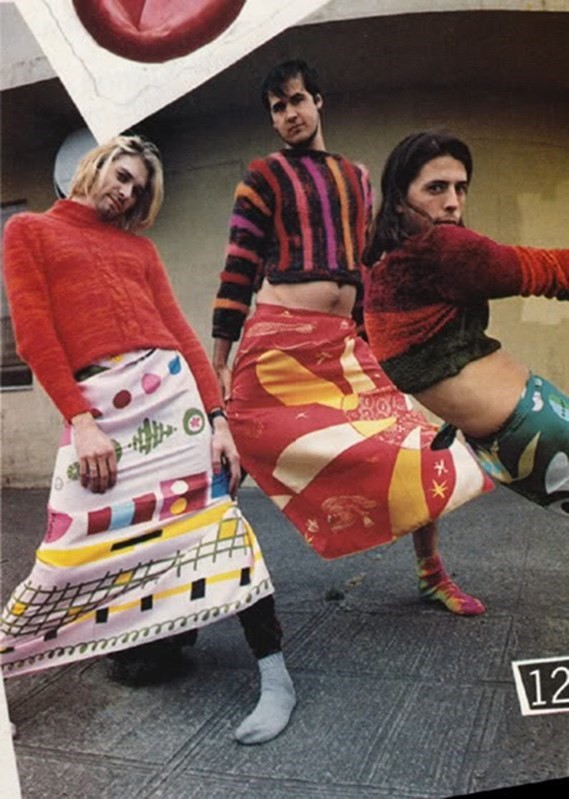

There is a newish joke which goes: “a male feminist walks into a bar — it’s been set too low.” In the cosmophagic, social-media-driven realm of the internet, influence is easy. In the 90s, being “woke” was a little more complex, so it also meant being divisive. Appearing in girly Dries Van Noten parachute pants in a magazine shoot with his bandmates, Cobain took a risk — even more so by saying he wished he were gay just to piss off the homophobes.

“Kurt Cobain was the antithesis of the macho American man,” The Fader editor Alex Frank told Vogue in 2014. “At a time when a body-conscious silhouette was the defining look, he made it cooler to look slouchy and loose, no matter if you were a boy or a girl” (a year later, the magazine put it more wistfully: “grunge celebrates the unkempt charm of youth, that brilliant and fleeting time when all imperfections are beautiful”).

Cathy Horyn, in the New York Times, disagreed. “Grunge is anathema to fashion,” she hissed, in a write-up of the Perry Ellis show for which Marc Jacobs, aged 29, was unceremoniously fired in 1992. “Rarely has slovenliness looked so self-conscious, or commanded so high a price.” The boundaries blurred here, too, between “boy,” “girl” and “other,” so that supermodels like Kate and Naomi — in Kurt Cobain cardigans — were now the sexiest slobs on the planet (Jacobs, scarcely by coincidence, still sells a murky-khaki nail polish shade called “Nirvana”). Posing for Stephen Meisel in the same year’s December edition of Vogue, Campbell, Nadja Auermann and Kristen McMenamy all looked both like and unlike the sullen gig patrons at grunge clubs, their flannel shirts recut in silk and their haircuts, done messily, worth several hundred in sterling.

By his own admission, Jacobs had never once visited grunge’s true birthplace, Seattle; this hardly mattered, however, this visual style being more about semaphore, sign, than the music — about a commitment to being expensively, outwardly uncommitted to anything other than, say, thick black eyeliner. Incidentally, when he sent Kurt and Courtney gifts of the show looks they had inspired, they set them on fire – as Love later recounted, “We burned it. We were punkers – we didn’t like that kind of thing.” But, in spite of this rejection of mainstream industry proclivities, by slipping on dresses Cobain had seemingly changed the fashion landscape forever.

“The thing about grunge,” the Editor-in-Chief of Details magazine assured the NYT, in a ’92 feature called Grunge — A Success Story, “is [that] it’s not anti-fashion, it’s un fashion. Punk was anti-fashion. It made a statement. Grunge is about not making a statement.” Twenty years after the look first broke, even Horyn had revised her opinion. “I find myself questioning my own reaction to the show,” she admitted for The Cut. “The violet-scented peevishness of my tone…I ignored, if I even considered, the charm and sweetness of the attitude — an attitude, by the way, which I happily embraced in my own brand of slob appeal.”

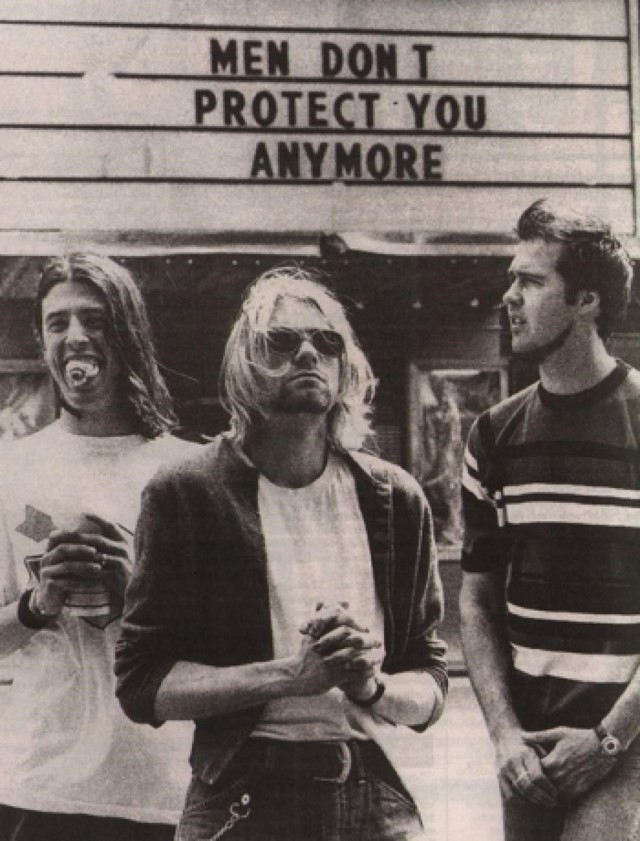

Photographed in front of a Jenny Holzer artwork reading: MEN DON’T PROTECT YOU ANYMORE, beaming and wearing a light, shrunken cardigan, it isn’t hard to see Kurt Cobain’s slob appeal, either; the whole band a group of unlikely, raw poster boys for a new kind of male thinking — one perhaps best defined by another loud Holzer text: RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY.