Gareth Pugh’s spectacular S/S16 collection was an ode to Soho, and the libertine nightlife the London district has played host to since the 1700s. Mini dresses with plunging necklines were covered from top to bottom with coin paillettes, a symbol of hedonism, refracting light and creating surface embellishment akin to the disco ball – and Pugh's decision to use them in this way draws on a long and rich tradition.

The origins of the word sequin can be found, in fact, in both the Arabic word sikka and the Italian zecchino, both of which mean ‘coin’ or ‘the mint’. The history of using coins to decorate garments has long been linked to the wearer's wealth; in the 13th century they were often sewn onto garments as a precautionary measure to keep them close to the body. By the 17th century, however, this tradition had taken on a purely decorative function with coins replaced by metallic discs known as 'spangles'. Since then, the sequin has manifested itself in a number of different ways, spanning myriad fashion genres. Here we chart its journey from practical to decorative, considering the 1920s flappers inspired by King Tutankhamun, and finishing up with the 1970s disco era so resonant in Pugh's paean to embellishments.

This 17th-century jacket is embroidered with floral motifs of rose, columbine honeysuckle, irises, daisies and pansies, strongly denoting the fashion for flora-adorned dress for women at this time. Among the lavish silk and metal thread embroidery lie a scattering of spangles, which in candlelight would have glimmered to spectacular effect. This is an early example of the metallic disc's use within the design of surface textiles. Over time, the word 'spangle' was replaced with 'sequin' in popular usage, which is believed to have begun in the 19th century.

In 1922, King Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, unveiling multiple splendours, from jewellery, chariots and thrones to perfume, wine and board games. Among the artefacts unearthed were robes embellished with circular discs, which, although tarnished, still retained their intended metallic surface. These relics proved the Egyptians had used an early form of the sequin to enliven the clothing of their monarch. The sensation caused by the tomb's discovery sent the world's media into a spin, and Egyptomania consequently took hold. Egyptian motifs appeared everywhere, penetrating the worlds of interior design, film and fashion, and sequins made a major comeback as a result – as evidenced by this sparkling Coco Chanel gown, worn by actress Alden Gay and captured by Edward Steichen.

Gay’s delicate back is exposed by the gown's plunging cut, and its sequin embellishments catch the light, adding movement to the image. Her poise and gesture evoke a pause between dances, the sash tied around her hips elegantly flowing into the forefront of the photograph.

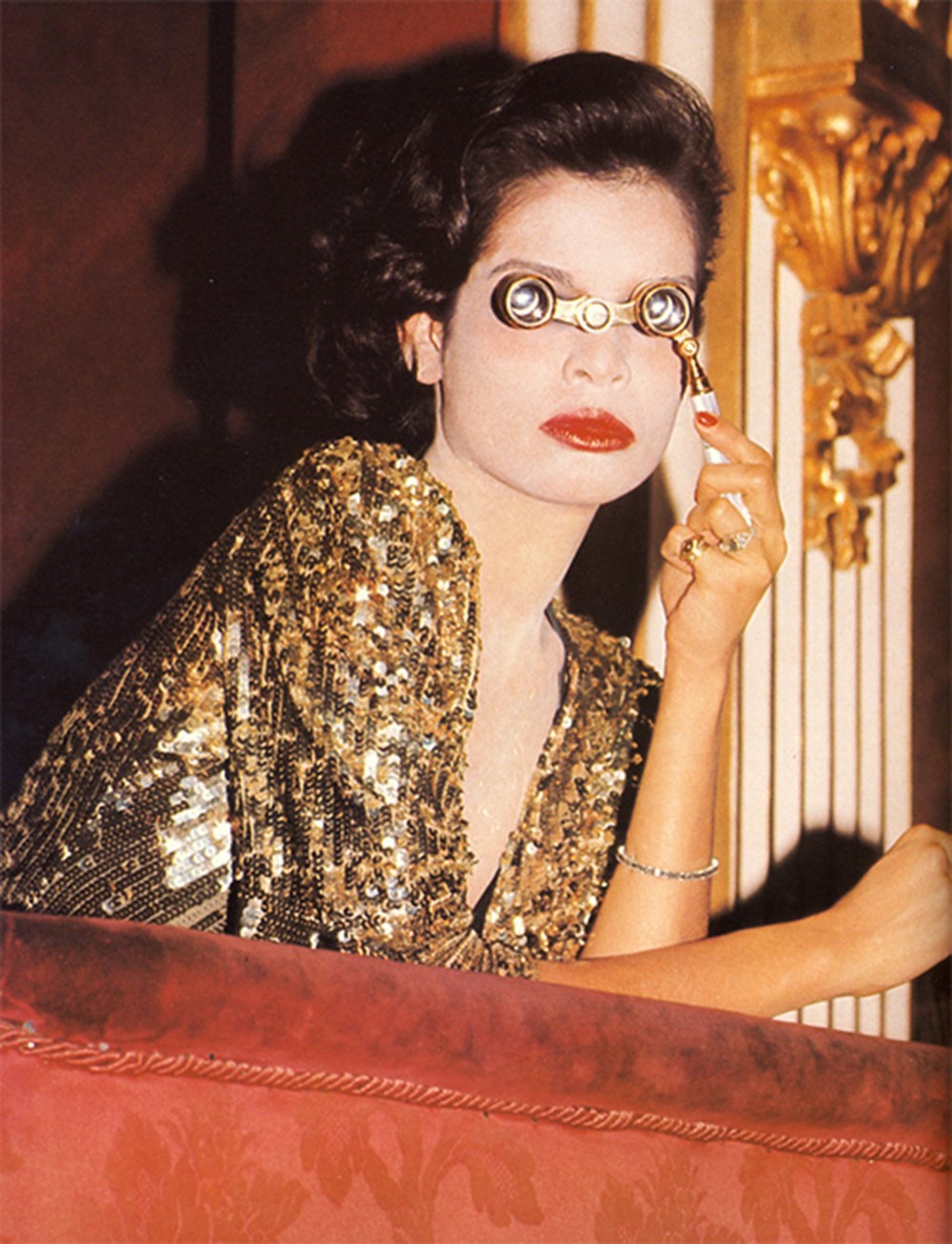

An article about disco was published in Rolling Stone magazine in 1973, and within a few months a burgoening disco fever had swept the globe. Bold colours, big hair and platform shoes formed the uniform of the new musical movement, while the sequin – its metallic surface catching the light on the dance floor just like a disco ball – soon became the motif of the moment. At the time, Vogue was hailed as a document of contemporary culture, and it duly embraced the changing tides: here it presents Bianca Jagger in the mode du jour, photographed by Eric Boman for its March '74 issue.

The shot sees the style icon gazing through a pair of opera glasses; the old world gilded stucco in the background seeming discreet in comparison with the glitter of her dress, which is heavily piled with gold sequins. The gown's deep neckline and ostentatious spangles, which would have been considered risqué in polite opera society, suggest that this image is a meeting of two worlds.