As a new play about Boulton opens in London, we spotlight the trailblazing life and legacy of the cross-dressing thespian

On the 28 April 1870, two middle-class men, dressed in full drag, were arrested outside the Royal Strand Theatre in London, where they had attended a show and (cue: gasps) used the ladies’ bathroom. They were thrust into jail, crudely examined – although no longer punishable by death, sodomy was a very serious crime – and soon became the subjects of a lengthy court case that held the capital enthralled. Dubbed the “he-she ladies” by the newspapers whose front covers they graced, they were, in fact, Frederick ‘Fanny’ Park and Ernest ‘Stella’ Boulton. Both were important early advocators of gay rights, but it is Stella who has earned the title of AnOther Woman for her sheer strength and determination to be who she wanted to be, and for achieving this with remarkable aplomb. Here, as Stella – a bold new play by British playwright Neil Bartlett – opens in London, as part of LIFT Festival, we take a look at her life and legacy in closer detail.

Defining Features

Ernest Boulton was born in Tottenham in 1848 into a family of stockbrokers. From as early as six years old, he enjoyed assuming the role of a female. He was a talented pianist and singer with a flair for performance – he is said to have frequently dressed as a maid and daintily served tea for the amusement of his family and their friends. By the age of 20, he was still living at home but, in Bartlett’s words, “making frequent forays into the West End dressed as an effeminate and fully slapped up queen”.

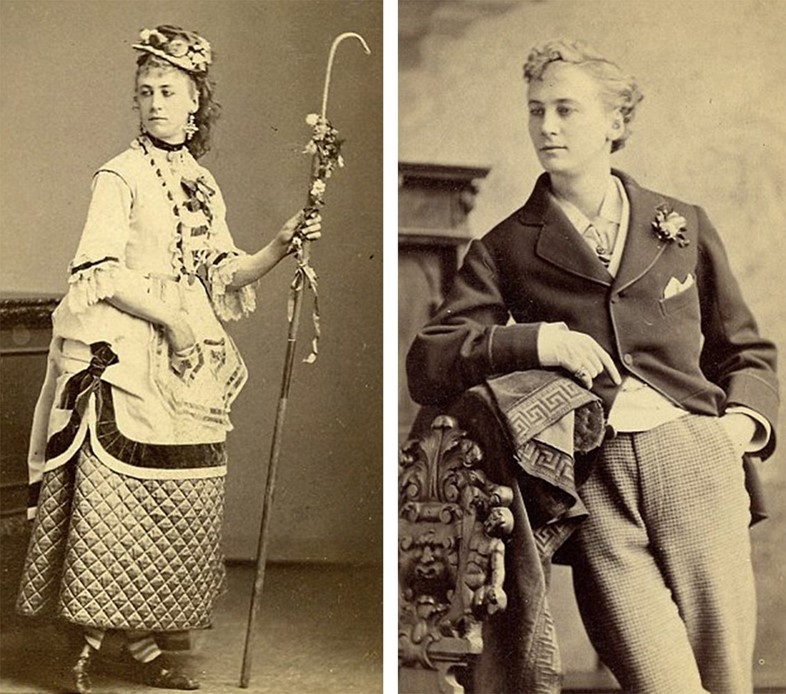

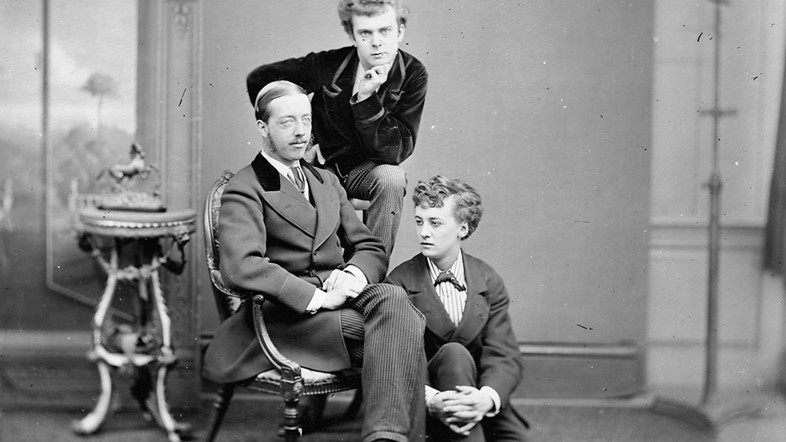

Sometimes this involved nighttime adventures as a flamboyantly dressed sex-worker, but it was as Stella – “a glamorous yet respectable young lady who appeared in female roles in touring melodramas [alongside Fanny],” as Bartlett describes her – that Boulton truly flourished. Stella was extremely popular, reportedly receiving as many as fourteen bouquets after her shows. She and Fanny were frequently invited to supper at country houses following their performances, wearing their stage clothes when requested, and local photographers would take their pictures for fast-selling postcards. By 1869, Stella had begun a relationship with Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton, a very wealthy young aristocrat, who made up for whatever he lacked in good looks with excessive generosity. He bought Stella a diamond ring and rented flat where they could sleep together as husband and wife. Prior to her arrest, it is fair to say that Stella was living the life of Riley; a true pioneer of the new glamour drag.

“I learned about Stella, while I was writing my first book – a queer history book, called Who Was That Man? – back in the 1980s,” Bartlett tells us. “And then it was the young Stella who I was very much drawn to. We’re always told that the 19th-century was all doom and gloom and shame for queer people, with Oscar Wilde and all that, and yet it turns out that there was this amazing young queen who was running around the West End in drag with an aristocratic lover and a wedding ring and this extraordinary alter ego, and who seems to have been utterly unafraid.”

Seminal Moments

It was in the wake of the 1870 trial, however, when this effervescent lifestyle was brought to an abrupt end, that Stella really went on to show what she could do. It took a year for the verdict of whether or not sodomy had been committed to come through: remarkably, the duo were found ‘Not Guilty,’ thanks to a shrewd lawyer who managed to persude the jury that no physical evidence could prove this to be true. Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton died before the case was through, rumoured to have committed suicide in a hotel room after being publically linked to Stella (although exile has also been suggested). But in spite of her newfound notoriety, and likely heartbreak, Stella was undeterred. “Conventional wisdom dictates that anybody exposed as a homosexual in Victorian London must have been shamed into obscurity,” writes Bartlett in the show notes. “Ernest, however, went immediately back on tour; he then dyed his hair blond, left the country and promptly reappeared in New York working as a singing glamour-drag act just off Broadway.”

After a few years of dazzling success, age began to catch up with Ernest so he changed his name to Ernest Blair and returned to Britain, where he would go on to tour for another 25 years. His final hit was the aptly named “Fading Away” which he performed in “a succession of increasingly down-market venues” (a moving rendition of the song is performed in the play by a mesmerising Richard Cant as the Older Stella). Stella died with very little money to her name at the age of 56 – the same age as Bartlett was when he wrote Stella. Her final breath was taken in National Hospital in Holborn, where she must, it is assumed, have been forced to dress in male clothes. It was this thought in particular, that encouraged Bartlett to revisit Stella for his poignant, beautifully realised play: a consideration of the final hour and fifteen minutes spent in her London flat before the arrival of the cab which would carry her to her fate.

She’s AnOther Woman Because…

In a time when gender fluidity is finally being confronted, and increasingly accepted, Stella’s story is of particular relevance. She has gone down in history as a daring transvestite of the Victorian age but her legacy and bravery in the quest for self-realisation is timeless. As Bartlett reflects, “Every baby comes out of hospital with a whole lot of invisible labels tied to its ankle saying, ‘You’re this gender, you’re this colour, you’re this class et cetera.’ And one of the great gifts that the Stellas of the world give us is saying, ‘Take all these labels off, look at yourself in the mirror and say, who are you?’ And it’s not just about living your own life, it’s about realising that everyone has the right to be themselves and then getting on and doing something about that. Right at the end of the play, Stella says, ‘This word happiness that we hear all the time – I want it. And I want us to talk about how I’m gonna get it, and I want us to talk right now’. That’s where the piece ends, you know... Let’s talk about that.”

Stella runs until June 18, 2016, at Hoxton Hall, as part of London's LIFT Festival.

Read more about Stella's story in Fanny and Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England by Neil McKenna, published by Faber & Faber.