On the eve of its centenary, the house of Balenciaga has staged yet another defining moment in its long history. The much-anticipated debut of Demna Gvasalia as Balenciaga’s artistic director has prompted enthusiastic reviews that foresee a new era for the historic Maison, as well as a renewed interest in the work and vision of its founder, Cristóbal Balenciaga.

Indeed, in his first collection for Balenciaga, Gvasalia has drawn on The Master’s aesthetic and formal vocabulary in an audacious yet respectful manner. The architectonic quality of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s tailoring was revisited in body-sculpting suits, while the founder’s lesser-known fondness for bold florals was reinterpreted in powerfully feminine dresses. But most strikingly, in Gvasalia’s contemporary vision, Balenciaga’s rigorously constructed cocoon-shaped jackets and coats were transformed into voluminous puffas, bombers and trenches, pulled back to reveal the nape of the neck, falling over the back in a somehow graceful arched curve. Surely, an intriguing interpretation of the so-called cocoon, the cut that lies at the heart of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s unique contribution to fashion history.

“Haute couture is like an orchestra, for which only Balenciaga is the conductor. The rest of us are just musicians, following the directions that he gives us” Christian Dior

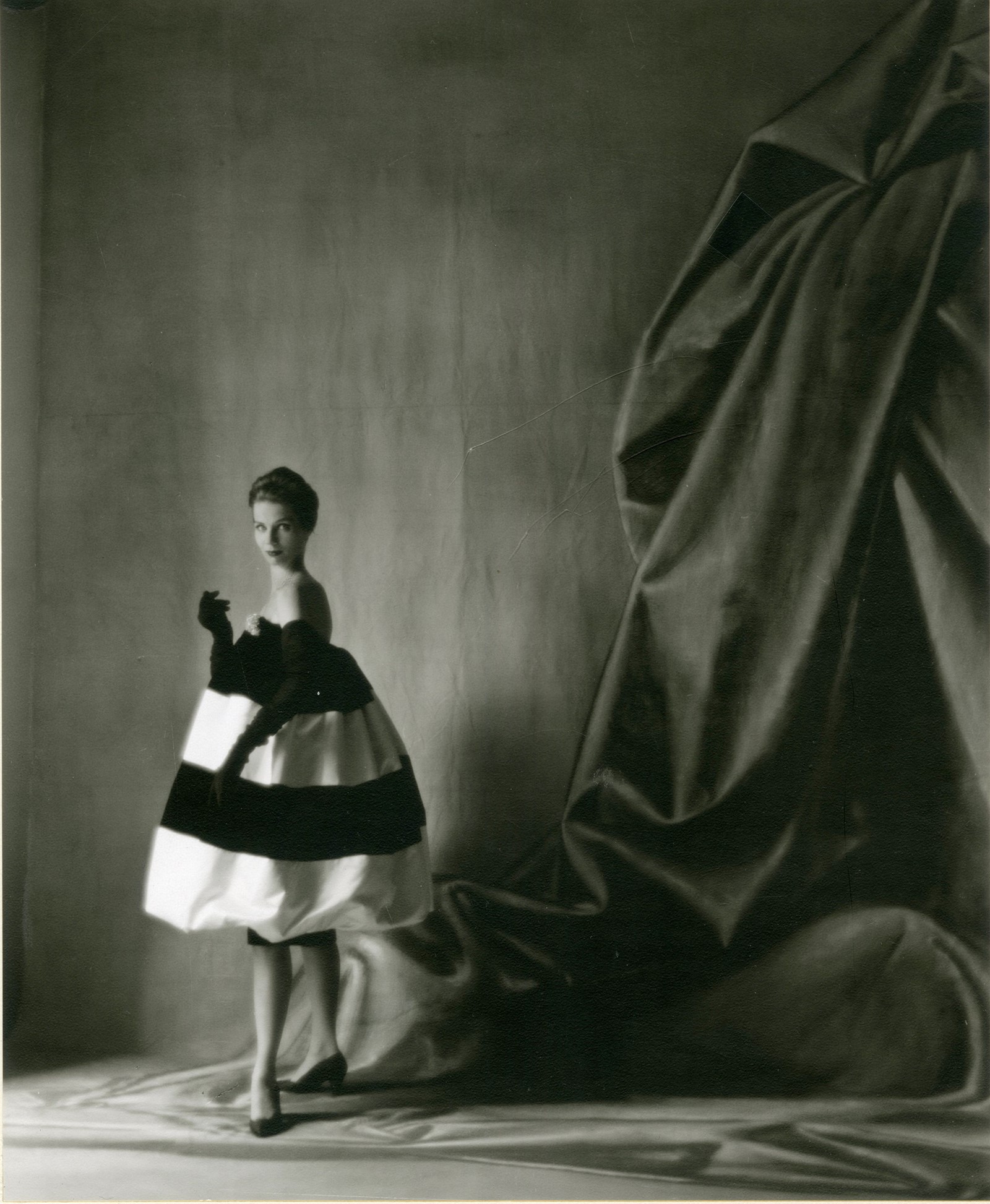

These words famously pronounced by Christian Dior in 1955, at the height of his own career, perfectly summarise Cristóbal Balenciaga’s undisputed leading role in fashion during the 1950s and 1960s. However, this didn’t always seem such an obvious development. When Dior himself captivated women around the world with the presentation of his first collection in February 1947, he was also launching the dominant silhouette of the 1950s, soon to be known as the New Look. Featuring rounded shoulders, a cinched waist, and very full skirt, the New Look celebrated opulence and a certain branch of voluptuous femininity. After years of military inspired fashions and sartorial restrictions resulting from war, Dior seemed to offer women exactly what they were aspiring to, even if this entailed reintroducing the corset in their wardrobes and in their lives.

In the early 1940s, Cristóbal Balenciaga had already initiated a creative path of his own, marked by a progressive experimentation with form and construction which aimed to establish a new relationship between body and garment. Balenciaga’s introduction of the cocoon silhouette played a vital role in this process.

This was closely related to the Japonism that influenced fashion at the beginning of the 20th century. Couturiers such as Paul Poiret, Callot Soeurs or Madeleine Vionnet incorporated the Japanese kimono into women’s dress, bringing with it an unfamiliar proportion that would revolutionise fashion over the next few decades. The characteristic arch over the back, the collar falling back to reveal the nape, the asymmetrical long hem, shorter at the front and longer at the back: these are the most definitive characteristics of this first Japonist cut.

Profoundly influenced by the work of these early innovators, Balenciaga used his own interpretation of the shape to depart from established notions of beauty and femininity in the middle of the 20th century. It was precisely in February 1947 when Balenciaga presented the so-called “barrel line”, a liberating, cocoon-shaped silhouette which obliterated the waist and offered women an alternative way of moving and experiencing dress.

Balenciaga’s commitment to rethinking the silhouette and searching for alternative volumes had not always been apparent in his work. In August 1939, driven by a marked historicism that pervaded all Paris couture collections of the season, he introduced his famous ‘Infanta’ dresses, which closely replicated the cut of seventeenth-century Spanish court dress, with its rigid bust and a tight waist, descending with stark contrast into a voluminous skirt with full hips. Balenciaga, ever the perfectionist, did not hesitate to use the most effective methods for reproducing the desired shape.

Thus, Rosette Hargrove, a correspondent for the Newspaper Enterprise Association, reported with significant astonishment from Paris: “Wasp waists are in again – despite the scoffers. Hips are also to be cultivated, if you want to wear some of the new styles convincingly. Rounded hips, in fact, are fast showing promise of becoming one of the canons of 1939 beauty, rather than the defect women have striven so hard to eliminate these past years. Balenciaga, the most recent and very successful addition to the ranks of the top-flight couturiers, had at least three of his mannequins wearing boned corsets. These simply took inches off their waists and made their hips bulge somewhat disconcertingly to the eyes of the unprepared onlookers.”

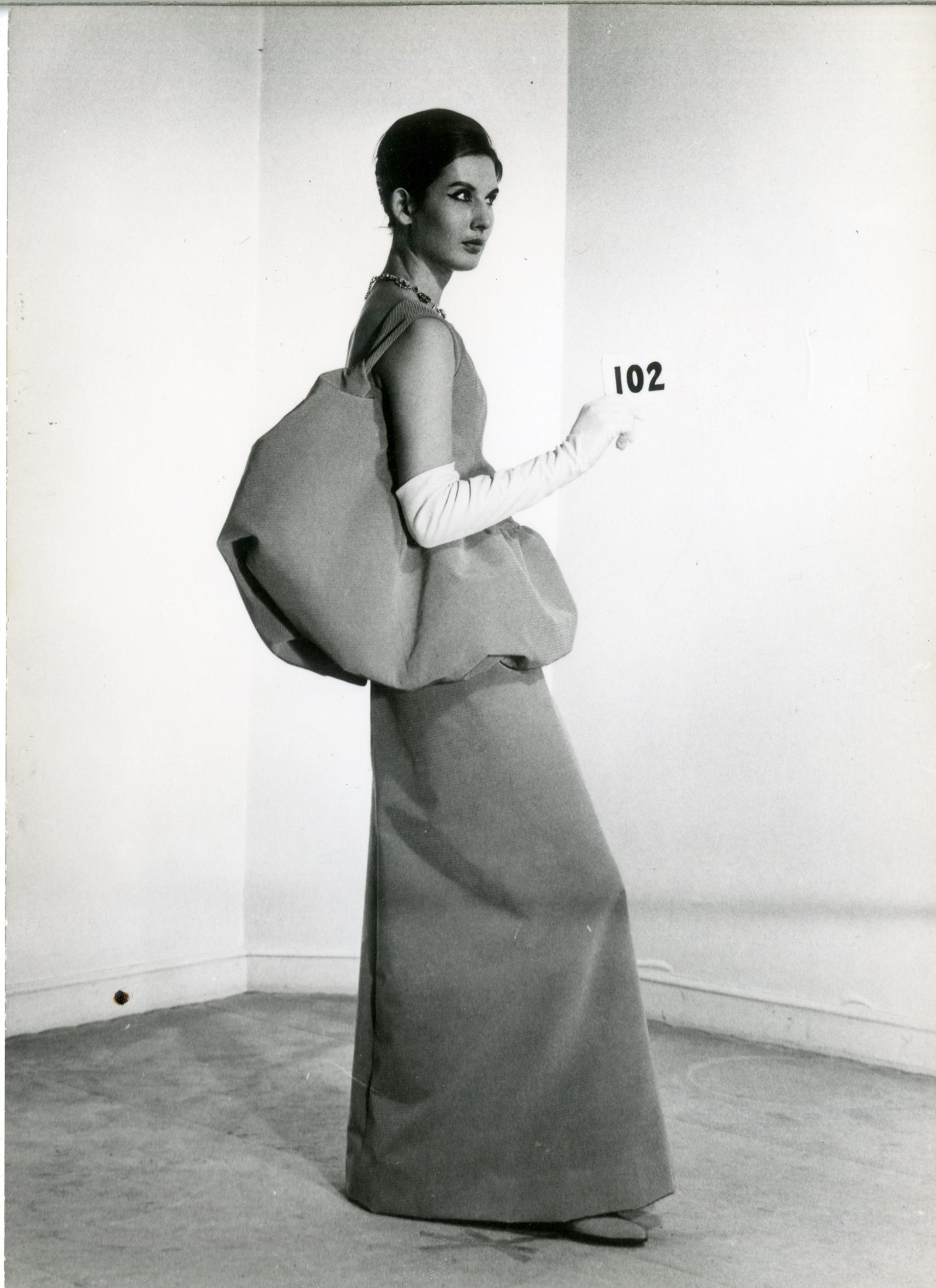

The outbreak of the Second World War and the occupation of Paris in June 1940 imposed a drastic change of rhythm upon Parisian fashion in general, and Balenciaga’s work in particular. In the summer of 1942, he presented a three-quarter-length jacket arching around the shoulders and broadening at waist-level before gradually narrowing out to below the hips. The piece in question, its curved shape reminiscent of an enveloping cocoon, stood in stark contrast to the almost military straightness of designs typical not only of that season, but of the war years in general.

Balenciaga was to perfect his hero cut in the summer of 1947, where three-quarter-length jackets and coats of identical profile were indisputably the stars of his collection. The cocoon became a classic on its own time and soon established itself as a solid alternative that most couturiers endorsed in subsequent seasons, including, of course, Dior himself.

In a similar vein to the way Poiret or Vionnet’s interpretation of the kimono liberated women from the constricting hourglass silhouette in the early 20th century, Cristóbal Balenciaga’s cocoon-shaped designs came to represent a liberating alternative to Christian Dior’s New Look. Beyond his masterfully tailored coats and jackets, he introduced a graceful version of the flowing silhouette into his day and evening ensembles, subjecting his own work to a progressive aesthetic and technical refinement until his retirement in 1968.

The cocoon has continued to inspire the fashion industry well into the 21st century. Its characteristic profile has been interpreted and revisited by the iconoclastic designers of the late 20th century, from Issey Miyake to Iris Van Herpen, as a powerful tool for reimagining and experimenting with the female silhouette. Demna Gvasalia’s most recent interpretation might stem as much from his desire to explore and reinterpret the heritage of the house he has come to lead, as from his uncompromising commitment to challenging conventional notions of form and beauty. A powerful combination indeed.

Game Changers: Reinventing the 20th Century Silhouette is at MoMu - Fashion Museum Antwerp until August 14, 2016 and an accompanying book edited by Karen Van Godtsenhoven, Miren Arzalluz and Kaat Debo is available to buy at Bloomsbury.