Quiet but resolutely powerful, AnOther traces the style culture of 'less is more'

It is one of fashion’s great ironies that, beyond the spectacle of the runway show, and away from the peacocking gestures captured by street-style snappers, many people working in fashion (those actually there to graft; applying make-up, frantically penning show reports in the back of taxis) are often dressed head-to-toe in black. American Vogue’s Grace Coddington, for example, might have art directed some of the most visually arresting, colour-drenched shoots the publication has ever seen, but she rarely strays from her signature all-black wardrobe.

This minimal approach to fashion could owe itself to the defiant nature of the industry’s creatives – after all, isn’t the punkest thing you could do when constantly presented with new fashions to reject it altogether and just wear one colour? It may also have something to do with professionalism, wanting to take a considered back seat, allowing the work itself to grab attention as opposed to claiming it for yourself. Interestingly, this approach bears similarity to the core principles of the minimalist artistic movement, which appeared in New York in the 1950s and 60s and railed against the overcomplication of bright, expressive colours and patterns, instead preferring to employ monochrome black or white as a palette cleanser, to refocus the mind and open up a new discussion around aesthetics. Here, we explore how some of the key components of the minimalist movement have manifested in the fashion industry...

Anonymity

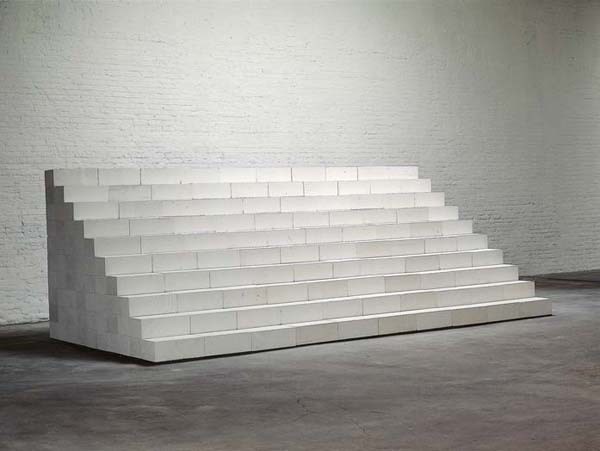

Although minimalist works are now famous in their own right, the actual construction of minimalist sculptures afforded them an anonymous feel, free of ego stamped all over like the works of action painters of the time, each who seemingly marked their canvases territorially. Works like Carl Andre’s sculptures, which were neither carved, built or modelled, but simply constructed by positioning raw materials like bricks and blocks with no fixatives to hold them in place, were a swerve away from the instantly recognisable works of characterful American painters like Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still and Hans Hofmann. As Minimalist art pioneer Sol Le Witt said, “Every generation renews itself in its own way; there's always a reaction against whatever is standard.”

A kindred spirit, both in terms of its minimalist aesthetic and the ‘invisible’ presence of the designer in the work, is the original incarnation of Maison Martin Margiela, founded by designer Martin Margiela, who upheld a sense of anonymity at the house until John Galliano was appointed creative director in 2014. The Margiela aesthetic not only feels in synergy with the minimalist approach – painting everyday items white, and repurposing ordinary household objects like crystal doorknobs – but equally in the way the designer(s) shied away from the limelight, instead letting the work stand for itself, even his models anonymised.

Monochrome as luxury

The minimalist colour palette is pretty strictly limited to monochrome black or white but, rather than simplifying its themes, taking colour and pattern out of the equation allows the work to explore bigger concerns as form takes centre stage. In fashion, Issey Miyake’s famous Bao Bao bags many have occasional, seasonal incarnations of colour variation, but are traditionally white or black, thus the geometric form of interconnected cubes becomes the focal point. Fellow Japanese avant-garde designer Yohji Yamamoto also tends to work only in monochrome, his reasoning, too seeming to be its low-key quality – as he once explained, “Black is modest and arrogant at the same time. Black is lazy and easy – but mysterious. But above all black says this: "I don’t bother you - don’t bother me’.”

The same can be said of plain white. Speaking in Afterzine in 2010, Peter Saville (the designer of Joy Division’s iconic Unknown Pleasures sleeve art and New Order’s Blue Money amongst myriad other iconic images) mused totally white minimalism design: “These are all responses to the overcrowded visual environment that we exist in. One response to that is to make things bolder and brasher. The other approach is towards the nothing. White space, white furniture – which is technical and laboratory-like – has an academic intelligence to it. It’s the suggestion of negative space as a modern luxury. It’s negative space as thinking space. It is a luxury. Time and space are modern luxuries.” His words echo almost the exact sentiment of painter Frank Stella, who produced a series of totally black works: “After all, the aim of art is to create space - space that is not compromised by decoration or illustration, space within which the subjects of painting can live.”

Minimal Music

A move towards minimalism wasn’t just a shift in visual culture in 1950s and 60s America; musicians also sought to create new, pared-down sonic spaces. Terry Riley’s ambient 1964 composition In C is often cited as the first minimalist work in music. The next year, New York musician Steve Reich composed It’s Gonna Rain, based around recordings of a sermon on the end of the world given by a black Pentecostal street-preacher, created using the favoured minimalist method of deconstructing and resequencing snippets using multiple tape loops. It’s a technique that would later be adopted by other experimental artists, one of the first being Brian Eno for My Life In The Bush of Ghosts. Fast forward to the present day with artists like Japanese artist/musician Ei Wada of the Open Reel Ensemble – who soundtracked the Issey Miyake S/S16 fashion show – are using similar techniques. Ei Wada’s trademark experimental sounds are made with a remodelled tape recorder.

Avant-garde fashion’s interest in experimental sounds doesn’t end with leftfield noise producers, other designers have played with silence and the ability of their designs to sonically punctuate their live presentations. “For A/W12 womenswear, Comme des Garçons' Rei Kawakubo carpeted her catwalk with velvet and added no sound, the models parading the collection only to the muffled clomps of their shoes, before a swell of electronica announced the finale,” wrote Harriet Baker in her report for AnOther. “And at the recent round of S/S15 shows, playing with the traditional MO has become more prominent, with houses tempering their musical soundtracks with noise or silence. Rick Owens turned down the volume on his classical soundtrack to draw attention to the serrated wooden clogs cracking down the marble runway.”