"The American cinema is a classical art, but why not then admire in it what is most admirable, i.e., not only the talent of this or that filmmaker, but the genius of the system."

André Bazin, 1957

"Studio filmmaking was less a process of collaboration than of negotiation and struggle – occasionally approaching armed conflict. But somehow it worked, and it worked well. There was a special genius to the studio system, and perhaps when we understand that we will learn, at long last, what Hollywood had been."

Thomas Schatz, The Genius of the System, 1998

People complained about the studio system. Stars, directors, cameramen, writers, art directors, composers, costume designers, even producers… many of them had an axe to grind about this system that churned out a manufactured product of dreams, belted it out in fact, making them work and work and work. Many yearned for freedom, free from the shackles of their studio contracts; some got it and tremendous, independent personal success and wealth followed. For others, there resulted a kind of oblivion. But in the end, they all seemed to miss what had gone before, this Golden Age, so bound up in and essentially part of a relentless commercial mechanism… Does any of this sound familiar?

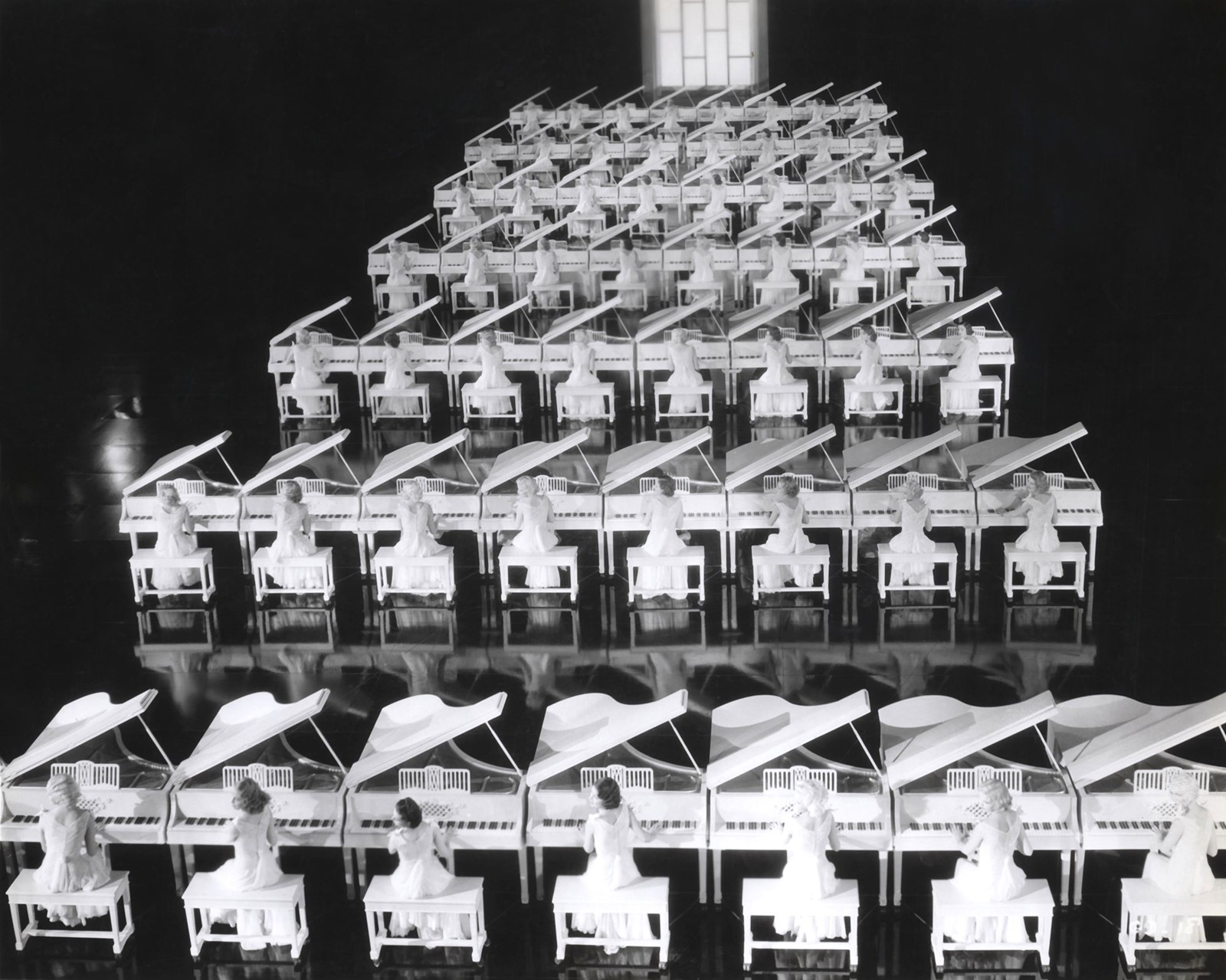

At the moment in the fashion industry, there is much talk of an unrelenting system, even a broken mechanism. The pace of fashion has quickened to such an extent that individuals involved are finding it hard both to keep up and to think up anything new. The demand for product, the instantaneous feed of imagery, the realisation that fashion is entertainment as well as physical things, with the public made more knowledgeable about the fashion system than ever before, has led to a constant cycle of want that the fashion companies and the media feel needs to be continuously fed. And yet, is it such a bad thing? These are the conditions in which Old Hollywood thrived in the Golden Age. That strange mixture of fast-paced creativity and quick-smart commerce somehow resulted in some of the greatest films ever made, some of the biggest and brightest stars and some of the best directors, cameramen, writers, art directors, composers, costume designers, even producers. And that’s the thing, neither the film studio system in the past, nor the fashion studio system in the present necessarily function as an individual pursuit with an all-knowing omniscient author: this is teamwork.

(Above image: The Gang's All Here, Busby Berkeley, 1943. 20th Century Fox / The Kobal Collection)

Is there a myth of 'the auteur' in fashion?

"There is this delusion that a designer or somebody’s name that is on a label is this great and powerful Oz. Everybody I know and is creative in some way influences me. I love the idea of a creative society, that notion of Paris in the past as a place for this kind of creative exchange between writers, artists and designers, for people who are just interested in culture. It is so normal that creative people are just drawn together. It is another reason for it to make perfect sense to credit people whom I work with, and be open and honest about it."

Marc Jacobs interviewed in 2007

"'We look like an anarchic company, because it’s so personal. But the soul of the company is very organised and good. There is a romance at its heart …’ Between you and your husband? I proffer. I often think of the legendary set-up between Miuccia Prada and CEO Patrizio Bertelli as being like a screwball comedy from the thirties. ‘Can we talk about it another time? It’s so personal. Let’s just say respect, love, passion and idealism are always there. And he is worse than me.'"

Miuccia Prada interviewed in 2006

Is the designer the great and powerful all-knowing "auteur"? That term, made famous in French film criticism, which puts the onus on the director as the primary author of a film, is almost equally accepted in fashion. But does it fit with what is actually going on today? In some ways, both Miuccia Prada and Marc Jacobs could be seen as both great and powerful auteurs of their brands – and this season, it could be argued they produced the defining collections of Spring/Summer 2016 that were both absolutely idiosyncratic and personal, autobiographical even. From the razzle dazzle of the Golden Ages of Hollywood and New York for Jacobs, to a more insular yet still celebratory collection about memories of a life for Prada, there was no denying the presence of these two authors. And yet the Prada mechanism, with the directed process involving many other people was more exposed than ever before, while Marc Jacobs has always been incredibly forthcoming about his debt to others in what he does.

There has also been a business partnership at the heart of these brands that has profoundly shaped the individual outputs. Until recently, Robert Duffy was the President of Marc Jacobs, jointly founding the brand with the designer, and equally credited with a personal and idiosyncratic business style. While the CEO of Prada, Patrizio Bertelli, who also happens to be Miuccia Prada’s husband, has an equally off-kilter business approach. Neither of them are merely ‘money men’; both could be seen to have contributed vastly to the creative risks and global profile of these brands. Unconventional and instinct driven, both the creative and commercial systems of these high fashion companies have worked in tandem together – that is not to say without a few blazing rows along the way. And it is both parts of the fashion studio system that need to be prized and protected from the slow and slowing encroachment of normality, conventionality and, dare it be said, the dreaded anti-instinct, ‘marketing.’

Fashion people are successful business people

"'When I took over Chanel it was not trendy at all. The owner told me ‘If it works you can do what you want. And if it doesn’t, I’ll sell the company.’ It worked and Karl Lagerfeld still does whatever he wants. ‘I love that. I like freedom – that is the most important thing to me. I am totally independent. My Chanel contract has no exclusivity whatsoever. My name over the door? I don’t need it – I cannot even cross the street.’ Of course Mr Lagerfeld is also the most famous and recognisable fashion designer in the world."

Karl Lagerfeld interviewed in 2012

Karl Lagerfeld refuses to speak to marketing people; he thinks it is a waste of his time. For somebody so instinct driven, who works at a lightening fast pace, together with an absolutely proven track record in making the right decisions for a business, it certainly is. And this could also be said for the majority of fashion designers who are the creative directors of brands. People do not enter the fashion industry without thinking of business, the communication of ideas and the hope for as large an audience as possible. While Chanel is the model of the dream fashion house that has made this fully materialise, much of the credit has to be given to Karl Lagerfeld. As he says himself, "I am totally enchanted by my organisation." And although enjoying his freedom as a ‘hired gun,’ he is very much in charge of it.

The Wertheimer family who privately own Chanel – made up of the two brothers Gerard and Alain Wertheimer – are the most fascinatingly discreet of any of the big business people in fashion. The family have historical business ties to Coco Chanel herself and have preserved the integrity of the brand, and nurtured its huge profitability since her death, largely by letting Lagerfeld and the rest of the creative people get on with it. "We’re a very discreet family, we never talk," Gerard was quoted as saying in an article in The New York Times in February 2002. "It’s about Coco Chanel. It’s about Karl. It’s about everyone who works and creates at Chanel. It’s not about the Wertheimers."

...But they're not necessarily cheap

"People who make a revolution are often called courageous and fearless. They are not afraid of changing the system when the system no longer works. I personally don’t like the word ‘revolution.’ I like the word ‘evolution.’ I always did. Evolution and not revolution. Evolution lives longer and looks better in history books. Revolution looks great, but only on TV. Revolution photographs look really well on the screen – drama, screaming, crying. Revolution is actually very photogenic. We live in a time that is very photogenic."

Alber Elbaz, International Night of Stars speech, October 2015

"Some producers find an unusual personality. They use up thousands of dollars to exploit it. They put the personality into a picture and the picture goes over and makes millions. Then, instead of letting the actor who does fine work go on doing it, they give him cheap material, cheap sets, cheap casts, cheap everything. The idea then is to make as much money from that personality with the least outlay."

Natacha Rambova, Photoplay, December 1922

Alber Elbaz, who, as its creative director, revived and made Lanvin into an enormously profitable fashion company has, of course, left the building after 14 years. His is an example of what happens when the equilibrium of the system falls out of balance. The whisperings have been about a lack of investment, penny pinching and continuous battles that had to be waged over these things by the creative director with the company’s majority shareholder Shaw-Lan Wang. In the end, it was some of these same arguments that contributed to the downfall of the Hollywood studio system, although they were made from the beginning – witness Rambova, the actor Valentino’s wife, stating these complaints in 1922. Nevertheless, without an understanding of or appreciation for the process of fashion by business people, or even a liking for those involved in the fashion world – Mrs Wang once told the Financial Times, "I don’t like those kind of people or those kind of parties" – then there’s going to be a problem.

The outsiders are the insiders in fashion

"If the Jews were proscribed from entering the real corridors of gentility and status in America, the movies offered an ingenious option. Within the studios and on the screen, the Jews could simply create a new country – an empire of their own, so to speak – one where they would not only be admitted, but govern as well. They would fabricate themselves in the image of prosperous Americans. They would create its values and its myths, its traditions and archetypes. It would be an America where fathers were strong, families stable, people attractive, resilient, resourceful, and decent. This was their America, and its invention might be their most enduring legacy."

Neal Gabler, An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood 1998

"They love him in every demographic: colored people, broads, fairies, commies... Gosh, we've gotta update these forms."

Jack Donaghy, 30 Rock, 2007

As Neal Gabler points out in his fantastic history of Old Hollywood, An Empire of Their Own, most of the ‘founding fathers’ of the studio system were Jewish people from a fashion and retail background. They were quintessential outsiders who invented their own kingdoms, revelled in their inventions and, as business people, were every bit as unconventional, charismatic, brilliant and inventive as any star or director they had under contract. They were impresarios that could find many of their counterparts in the fashion world today – in charge of fashion houses. Despite the slowly creeping normality and the blandly complacent element filtering through fashion, it’s still an island of misfit toys – and all the better for it. This is the magic element of the fashion studio system, where all sorts of disparate people from different backgrounds are brought together to create something special for the outside world, including, as Jack Donaghy might say, people of colour, broads, fairies and commies. That’s because the fashion industry is also the audience for fashion – they are never far from removed from the public’s tastes.

I want to be alone

"I am fed up with stuff that isn’t perfect. Affecting casualness is every bit as precious as being precious and I am going to be as refined and elegant as I can. I am going to make my interiors as perfect as they can possibly be. At the factory I need it to be exactly the way I want it to be, so why should I compromise elsewhere? It is very A Rebours, [J K Huysmans' Against Nature] very Jean des Esseintes, its hero and my hero. I plan to shut myself away more and more and more… And you know when people talk about designers’ losing touch with reality, like that’s a bad thing – I plan to lose touch with reality. And the more I lose touch with reality, the better I’ll get… I think."

Rick Owens interviewed in 2015

"I am very interested in the idea of the fragment, these fragments of the past that form the future. I want a soft, soft, soft futurism."

Raf Simons interviewed in 2015

Raf Simons and Rick Owens were once seen as the quintessential outsiders/insiders of the fashion world, but does this still hold true? They have both made a resolute crossover – one through the fashion studio system and the other by his very refusal to enter it, although now neither are part of it. As Raf Simons has left Dior, simply because he wanted to – there really are no conspiracy theories here – he still has an appreciation for the fashion studio system and Bernard Arnaud as a visionary business person. After all, LVMH is the equivalent of Old Hollywood’s MGM: More stars than there are in the heavens. Simons is, at present, sampling a fragment of that calm, soft, soft, soft future that was the inspiration for his final show for Spring/Summer 2016 at Dior. Rick Owens is more of a flagrant example of free will in the face of the fashion system. While other, far more conventional independent designers are struggling, Owens is getting ever stronger and expanding his operation. His is a multi-hundred-million dollar independent company to be reckoned with – and he has refused offers to buy his company on more than one occasion. Instead, he reigns supreme, remarkably designing all the products himself – "It would freak me out to put my name on something somebody else had done." – he is the author of his own brand and life, and in many ways, he is his own best creation. He also may be more of the shape of things to come.

A version of this essay appears in AnOther Magazine S/S16