Alexandre Singh is one of the most acclaimed voices in the contemporary art scene. In all aspects of his work, he continuously addresses the dialogue and disconnections between art, culture and the world...

Alexandre Singh is one of the most acclaimed voices in the contemporary art scene. In all aspects of his work, he continuously addresses the dialogue and disconnections between art, culture and the world and his work has been exhibited in numerous venues, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; PS1/MoMA; the New Museum, New York. Represented internationally by art: concept, Paris; Metro Pictures, New York; Monitor, Rome; Sprüth Magers, Berlin/London, he has had solo shows at institutions including Palais de Tokyo, Paris, in 2011, and The Drawing Center, New York, in 2013, where he was the youngest artist to have work shown in the main galleries. He is currently working on a play entitled The Humans.

How would you connect fashion to elegance?

Does elegance exist solely in the eye of the beholder or does it have an essential substance? Obviously, there are people and things quite outside of the purview of the fashion industry that are elegant. Sometimes it feels like elegance could be ‘the thing in itself’ to which the fashion world is forever addressing itself – trying to grab hold of and reproduce its mysterious essence. Fashion is thought of as being about the buying and selling of clothes, yet whenever one reads a fashion magazine it appears to be as much to do with the cultivation of an aesthetic sensitivity in every part of one’s life: the furniture, the house, the make-up, the satchel, even the cat. And elegance is probably the word that summarises best, what this heightened sensitivity aims to inculcate.

What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

In my life they’re surprisingly detached. I have a fascination for and love of historical clothing: in paintings such as Rembrandt’s; or in the case of theatrical costumes; for example in Kabuki theatre, Greek theatre, Elizabethan theatre. I would love if I had the time and energy to dress myself as an Edwardian gentleman, the whole aesthetic of that era particularly appeals to me. But I can’t really relate that personal interest in historical clothing to contemporary fashion: perhaps I’m too dazzled by the spectacle of the catwalks to be able to connect these traditions together…

"Sometimes it feels like elegance could be ‘the thing in itself’ to which the fashion world is forever addressing itself – trying to grab hold of and reproduce its mysterious essence"

Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did?

Undoubtedly. Everything is a discourse; clothing especially. As to what that discourse might be specifically, it’s hard for me to say. I wonder if there’s an – pun intended – emperor’s new clothing quality to fashion’s own internal discussions? Let’s be honest: fashion has a reputation for being at times shallow. If not all the participants clearly understand or agree on the criteria by which clothes are being discussed and evaluated, then there’s an strong potential for people to end up talking at, rather than to each other.

That said, the actual nitty gritty of the formal and historical aspects of clothing is fascinating; extremely rich, and, to a great extent – unappreciated by the many lay people who flip through these magazines, the very ones who end up buying the clothes. You’d need to talk to a real maker of clothes in order to get a sense of the immense complexity of these things. Couture has a great tradition of formal and technical language, that is perhaps lost to its casual consumer. In that respect it greatly resembles poetry.

The word "intellectual" was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

Well you have your sans-cullotes for one...

How would you relate the concept of "fashion" to the one of "style"?

Some people adhere to a single brand: for example dressing exclusively in Comme des Garçons. However to be fashionable and interested in fashion implies that you’re able to judiciously select from a variety of these pre-made universes, assemble components from each, and thus create your own look. This is a huge ask of the consumer. And also a somewhat false ideal. You can’t truly love for example Vivienne Westwood, and Yohji Yamamoto, and Hugo Boss. Each of these houses espouses such different aesthetic sensibilities – especially those with such an idiosyncratic quality as Vivienne Westwood’s. At the same time Vivienne Westwood is itself a contradiction in terms: you can’t be punk and spend £600 on a jacket…

What does fashion have to do with intellectuality?

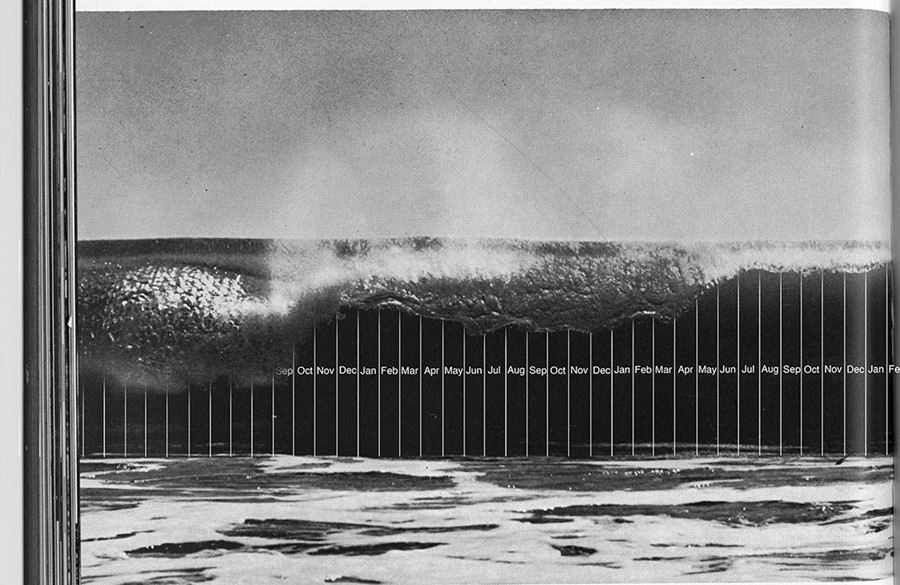

They have something in common, in the way that fashion incarnates the continual passage of time. A monstrous engine of never-ending change forever surfing the wave of the present. Fashion not only articulates but embodies this sense of time slipping through our fingers. Which is a subject that tends to preoccupy intellectuals.

"Fashion not only articulates but embodies this sense of time slipping through our fingers."

Your work as an artist continuously questions the category of fiction. Do you see fashion as a fiction as well ? And what kind of fiction would it be?

So much of fashion originates in a fetishisation of youth, and beauty. The same late adolescence and early adulthood so beloved by the Ancient Greeks: the age of beautiful ephebes. Fashion seeks to eternally evoke and preserve this fleeting point in every human being’s life. This can make fashion seem at times incredibly melancholic, even touchingly sad. Once one leaves this youthful period of one’s life, the remaining years are spent looking forlornly back to that idealised state. The body decays. And a little later crumbles to dust.

Ironically, this same decay of the body is inversely correlated to the acquisition of wealth. Hence the fetishised youths that populate fashion shoots dressed head to toe in designer rags could never afford those clothes. And it’s really decrepit older people – able to throw down a small fortune on the right outfit – who are the real clientele. It’s one of those ironies of life that, whenever you see a Ferrari flying by, it’s more often than not the arthritic fingers of some OAP curled round the steering wheel, rather than those of the dashing 20 year old Italian Viscount of popular imagination.

One of the things that’s fascinating about fashion houses are the campaigns they put together. Each brand presents its own signature fictive universe: Burberry’s for example, is one populated by raincoats, aquiline British people, rain, trees, country houses; aristocrats – everything seen through black and white. The American counterpart might be the WASPy worlds of Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger. Youths on boats; playing polo. Each designer’s clothes are seen as existing in a parallel world: a fictive cosmology that’s usually quite consistent throughout their entire career.

You use references from every time period, and bring them together in your works. What relation does fashion have to time passing?

Fashion, like sports and farming, is a perennial activity. It relates not only to the passage of time but evokes cycles of death and rebirth. I often wonder if the fashion world is aware of this ritualistic, Druidic quality to their work. A whole enterprise devoted solely to the declaration of the passage of the seasons: Summer into Fall, then dying in Winter, only to be reborn each year in Spring.

Grim faced mannequins stride up and down the catwalks whilst elder priests cackle gleefully. Their beady little eyes fixed on the youthful flesh, here for a moment, to be soon replaced by the next sacrificial offering. Hands over mouths whisper, and make notes, and together they haruspicate: the editors divining what shape the next season might take.

In two weeks Donatien will be interviewing Harold Koda.