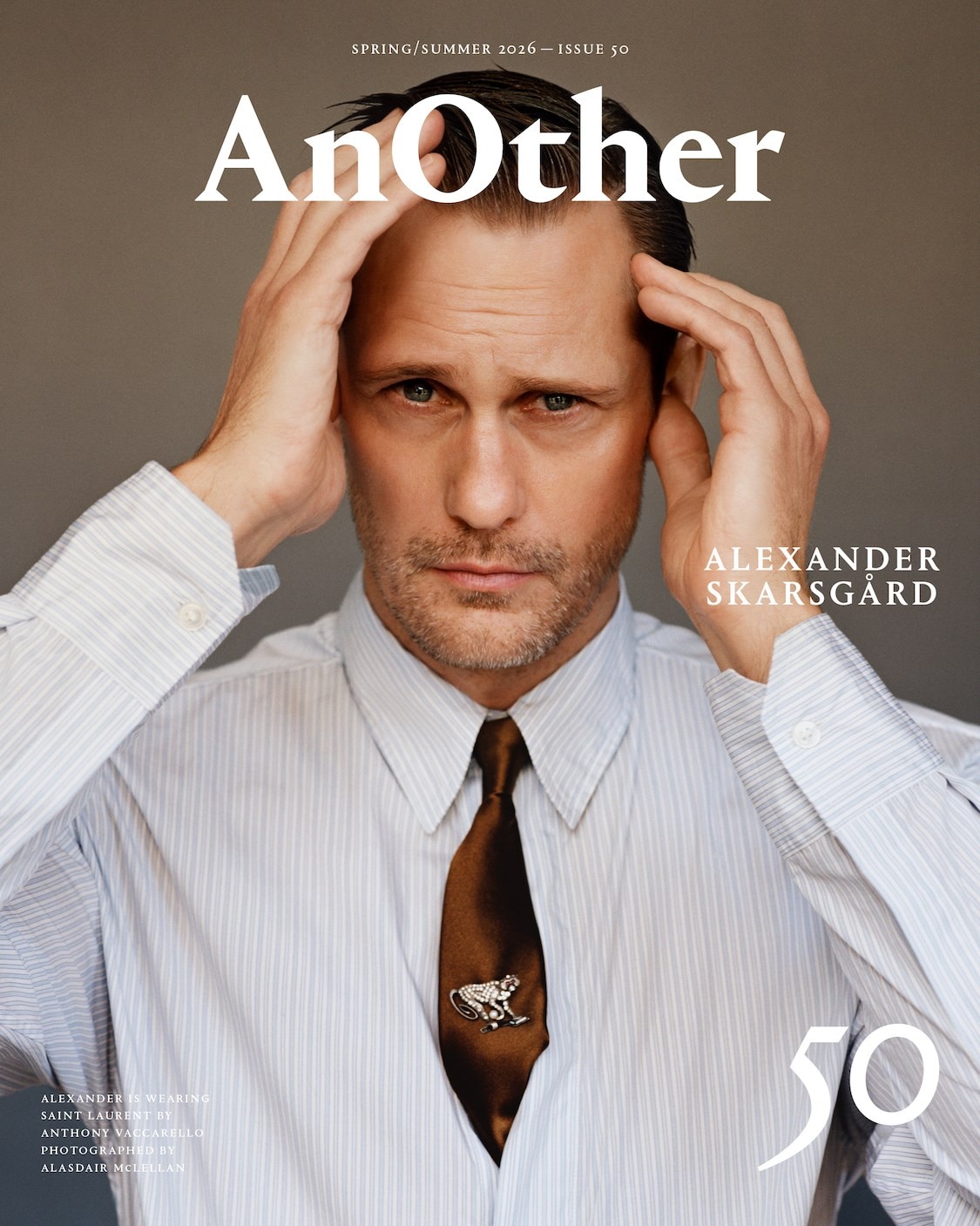

This story is taken from the Spring/Summer 2026 issue of AnOther Magazine:

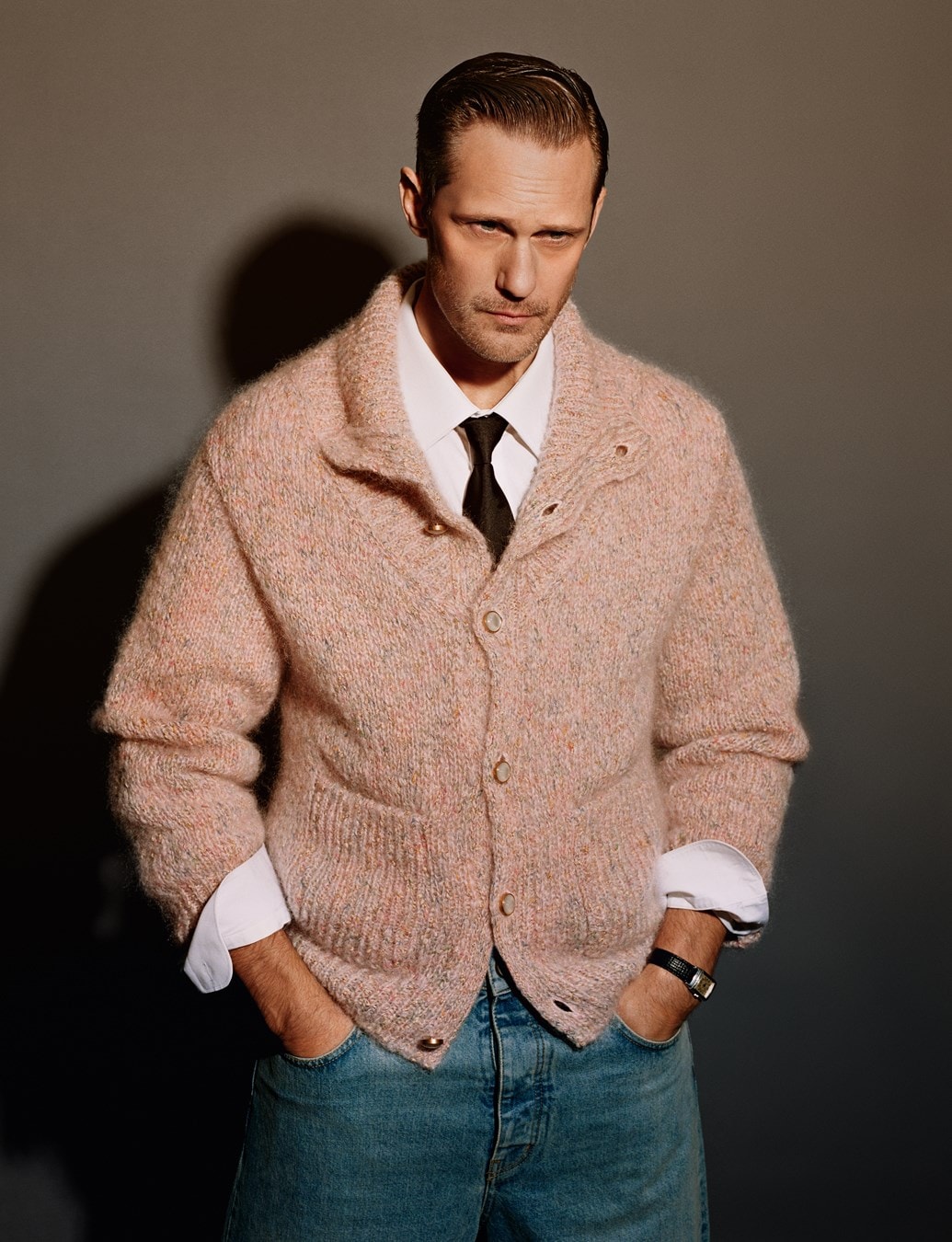

I am waiting for Alexander Skarsgård in the tearoom of a London hotel. Under normal circumstances and given his celebrity, the Swedish actor and I would be in a hushed corner or private room.

Instead we are sitting in the middle of a glittering lounge, beside a golden Christmas tree surrounded by a miniature train. Our armchairs are also gold, and very small. As is the tiny British finger food that the management insists we order. Skarsgård, who is not small in stature or fame, is grinning wolfishly at me as I try to fend off the attentive waiters, who for some reason, perhaps because of the Hollywood actor in their midst, want to bring us specially brewed herbal tea in, once again, miniature cups. Just when it has been agreed that we can have two black coffees rather than five courses of picnic food, bite-size sausage rolls appear. Skarsgård takes one in his elegant hand and eats it whole. We’ll have the sandwich flight, he tells the waiter. It’ll be a competition to see who can get to the middle first. As the mise en scène in which I find myself becomes more improbable I become redder than I have ever been, the colour pulsing hotly up my neck. And thus we settle in to discuss Pillion, the film in which he plays a brooding, gay, leather-clad biker in a relationship with an eager submissive.

Brooding is an apt word for the roles that have made Skarsgård famous over the course of his four-decade career. With the exception of 2001’s Zoolander, in which he plays a dim-witted model, he brings a subtle intensity and sense of unspoken threat to his work. He caught the popular imagination as Eric Northman in the TV series True Blood, which brought vampires, gore and graphic sex to the small screen. In Lars von Trier’s Melancholia he is jilted on his wedding day almost immediately before the end of the world. The Legend of Tarzan, which starred Margot Robbie alongside his newly bulked-up physique, and Godzilla vs Kong, which rejuvenated the cryptid genre, made him a rare action star outside the various superhero universes. It was HBO’s Big Little Lies, however, that took his stardom to the level reserved for those both very good at acting and very good at being an actor (a complicated combination). Playing Nicole Kidman’s abusive husband, he expressed both vulnerability and an ever-present menace to millions. Since then his status has been cemented with work including Robert Eggers’s The Northman (naked Norse menace, once again with Kidman) and Succession (menacing tech lord).

Pillion is Skarsgård at his very best. In the opening moments of the film, shy Colin, played by Harry Melling, locks eyes with Skarsgård’s Ray in a pub. Colin is in an a cappella group and being set up on dates by his dying mum — Ray is in full leather, lives alone and is in a bike gang. He promptly lures the Bromley naif down an alley for oral sex before they enter a sub-dom relationship in which Colin cooks him dinner and cleans in exchange for sessions spent wrestling in singlets and some light penetration.

In the context of kink, Skarsgård’s ominous undercurrent is subdued — everything happens within the rules of the sub-dom relationship and the only actual pain caused, some titty twisting aside, is to Colin’s heart, as he longs for something beyond role play. The film is at times heartbreaking, moving beyond the sexually charged source material to something transcendental. Why do we love? Why do we die? Why can’t we settle down with the nice gay man in a Kylie T-shirt that our mum set us up with on her deathbed instead of getting pissed on in a dingley dell surrounded by mohawked bikers? Somehow the director Harry Lighton’s film makes the highly specific feel universal.

When we meet, Skarsgård has been promoting the film worldwide in a selection of leather get-ups on the red carpet. Also on a press tour, for Joachim Trier’s new film, Sentimental Value, is his father, Stellan, who has credited his children, six of whom act (the other two are a doctor and casting agent), with turning him into a “nepo daddy”. In Stockholm, where Alexander and Stellan both now live, they usually miss each other, so Skarsgård the younger has been enjoying some family time with his father. Just as we finally make our way through the last tiny cake, none other than Nicholas Galitzine, in heroic shape to play the new He-Man, bounds up, claps me manfully on the shoulder to apologise for interrupting and announces he’s been filming in Western Australia with Skarsgård’s younger brother Bill. The pianist strikes up Adele at one point. It’s very romantic and Skarsgård is highly amused by my awkwardness at the situation, going so far as to mime a proposal. We converse and I work up the courage to ask about Pillion’s big pierced-penis moment, among other things ...

JACK SUNNUCKS: We’re in this beautiful setting.

ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD: The perfect contrast.

JS: Often when I see gay films, they’re really, really sad. This was heartbreaking but outside the genre of “gay man knows love for two days and then spends the rest of his life lonely and sexless looking out of a window in Maine”. This was very different, in that, for me, it had a happy ending. What did you like about the script when you first got it?

AS: Tonally, it really stood out. It felt unique and I agree with what you just said. [More food arrives.] We need an extra table. It’s going to be a lot of food.

Often the sub-dom or kink subcultures are depicted in a very dark, scary way. Cruising [William Friedkin’s 1980 crime thriller, starring Al Pacino as an undercover cop tracking down a serial killer] is a good example, where it’s like this dangerous underbelly of society. Like you’re supposed to be intimidated. What I loved about this film was that it wasn’t that, but it also didn’t dip into the sentimentality of the violins playing, a new love for a second and now I’m sad, staring out the window. It felt irreverent and fun and charming and I really cared about these guys, this couple. It’s so rare to read something wholly original where I’m like, “I haven’t seen this depiction of any subculture before.” I thought Harry [Lighton] had beautifully approached this subject matter with curiosity and respect, but not too much respect, because if you do it with too much respect it’s a veneer, it’s a Disneyfied version – “Look how great they are.” I love that he wanted to show this world, let it be awkward and stumbly and weird and funny at times.

“Often the sub-dom or kink subcultures are depicted in a very dark, scary way” – Alexander Skarsgård

JS: It’s also so graphic that it’s not sexy. Cruising is a sexy movie, and Pillion, for me, had its moments but it reminded me of the real-life leather people that I’ve seen, and biker people, and it’s usually quite normal-shaped people. They just happened to be wearing a dog collar and be crawling around on all fours.

WAITER ONE: Sorry to interrupt. This is a little welcome drink from us. It’s a very Christmassy blend, berries and cinnamon spice.

AS: Thank you. Harry was interested in the contrast between the outlandish aspects of it compared to mainstream society and how extreme it would be in other people’s eyes and letting these scenes be intense and sexy, but also contrasting them with mundane activities. He tells this story of how, the first time he was out with GBMCC guys [the bikers in the film were cast from the Gay Bikers Motorcycle Club, Europe’s largest LGBT+ motorcycling club], he was struck by how, quote-unquote, normal they were.

JS: The camping [Colin and Ray go camping in the film].

AS: Yeah, the camping. And they stopped at a pub for an orange juice as they were driving to this meet, and they were talking about how foxes were encroaching on the suburbs of London – it was such a mundane conversation. I think he wanted to, if not capture that specific conversation, get the essence of that into the movie, where it doesn’t have to be extreme. You can go from an orgy in the woods to Sunday roast with the parents.

WAITER TWO: Hello. I’ve spoken to my manager. If you want to just have something isolated, we can do à la carte for you.

JS: That’s really kind. Often there’s so much threat in the eyes of your characters. And a placid exterior. I’m thinking of Big Little Lies. The Northman is generally quite out-there violent. Was there any backstory prepared for Ray or was it, “I’m coming in and I’m just not going to say anything”?

AS: Well, I knew that I didn’t want the character to be …

WAITER TWO: Do you want champagne as well?

AS: I’m good, thank you so much. It was important that I didn’t want him to be chatty, obviously. I wanted the communication between him and Colin to be the bare minimum, at least initially. It’s basically giving orders and then you can soften it a bit. In the beginning, it’s also a reading of Colin, because he’s a novice. This is his first submissive endeavour. I’m giving an order and seeing if he is down to play this game. And then trying to shape Colin, in a way. In terms of backstory, I love that Ray is very enigmatic and that he maintains those enigmatic qualities throughout the movie. Colin never finds out anything revelatory about Ray in a big climactic moment. I think there are screenwriting tropes you could easily fall into.

JS: I was waiting for a violent act, a revelation.

AS: In a way, I was too. The first time I read it, I had no idea who Harry [Lighton] was. I didn’t know who had written the screenplay. I was just reading and feeling so invested in this relationship and these characters, and slightly nervous because many versions of this script would have had that big climax – “We need a big clash between the two.” I was so relieved that didn’t happen, that [Lighton] maintained that enigmatic quality throughout.

JS: The confrontation between Ray and [Colin’s mum] Peggy is very British, and for me it was very violent. It was the only real act of violence in the film. She says to Ray, “I think you’re a cunt.” And because the film had been so restrained until then, in that moment I could hardly breathe.

AS: It’s intense. I loved shooting that scene because I could see both points of view. It wasn’t like, “Oh, she’s bigoted.”

JS: No, we see her efforts to find her son a partner.

AS: Very much so. She’s just a loving mother who is concerned about his wellbeing, his happiness. And she’s not wrong. He’s not completely happy at that moment. But I also love that Ray is not, to me, the villain either. He’s very upfront about what type of relationship he wants. He’s very upfront about the fact that he doesn’t think going to dinner with the in-laws is a good idea. Colin kind of pushes him into that by playing the “my mum is sick” card. So Ray is like, “All right, I’ll go, but I’m going to be who I am. And if she’s not happy about that, that’s her issue.”

JS: It’s a film about control. Colin’s mother is dying and I imagine he wants to be in control of just one thing – or to be controlled. When everything’s going to shit … [The hotel pianist starts playing Adele.] This is very romantic.

AS: [Mimes proposing.] Here’s a ring.

JS: It’s one thing in Colin’s life that has very clear parameters and rules, whereas real life doesn’t. Real life is really tragic.

AS: I think Ray, in the first scene in the bar, can sense that from across the room – that he’s potentially quite an interesting prospect. They’ve never spoken, but the way Ray approaches, gives that look, puts the coins on the counter … He can smell that Colin is a little lost and that this type of relationship might appeal.

JS: I have to ask about all the sex. Well, not all the sex because there’s actually not that much. But in the wrestling scenes, for example, the humour is so inherent when often people take their kink communities very seriously. So I wondered what that atmosphere was like on set. Was there laughter or … [The actor Nicholas Galitzine comes over to talk about filming with Bill Skarsgård and how much he wants to visit the family compound.]

AS: Sorry about that.

JS: The sex.

AS: The sex. Was it funny? Well, I think it is quite a funny sequence, but obviously the key to shooting a sequence like that is to do it seriously. Ray is not laughing about it. It would have taken away from the scene if Ray was giggling about it. No, this is real.

JS: Well, the threat of violence means that, through the whole film, you’re wondering whether there’s going to be some actual karate chopping, and there isn’t because it’s all regulated and within these rules.

AS: Especially the scene in the back alley, because it’s obviously the first time for Ray and Colin – it was important to get that tonally in the right place because we wanted it to be very clear what the dynamic was, the sub-dom relationship. And that Ray is incredibly private, doesn’t introduce himself until after the act. But it’s important to feel, to share, Colin’s excitement about this. And when we did the first take I was a bit more forceful, I think – not manhandling him, but I spoke even less and showed physically what I wanted him to do. And the blow job was a bit more like … [He looks around.] It’s strange with kids sitting around here … but he was gagging a bit more and I was holding his hair. It was quite interesting because, after that, we got together and all felt that, no, it got too dark. It’s important to come away from that scene the way it is in the edit now, with a slight smile on Colin’s face.

“It’s great that we’re living in a time when more people feel comfortable shouting out what their sexual preferences are” – Alexander Skarsgård

JS: It was kind of sweet in the end.

AS: It’s kind of intense. And he hasn’t experienced anything like that. I don’t think it was scary for him, but it was definitely, “Whoa, I’m in this back alley with a stranger, what’s happening? I’m being dominated.” But you want him to come home and feel, when he sits down and touches the wet stain on his knee, a level of excitement and a thrill. I think it’s important in that moment for the audience to be like, “I hope there can be a second date because this could potentially be interesting.” Rather than, “Fucking call 911, there’s a predator on the loose.”

JS: Most people’s parents would like them to be with someone, anyone really, who is kind of solid. I can feel Colin is like, “I’m with this really handsome man who wants to be with me. Leave me alone.”

AS: That’s another thing I liked about the script. The conventional story would be that the parents are a bit more conservative and by the end of the film they’re accepting him and his sexuality. I love how funny and sweet it is in the beginning and that they’re all cheering him on. They’re really pushing for it. But then they go, “Wait, are you really happy about this? You have to shop and cook on your own birthday.”

JS: You studied in England for six months – what was your concept of the British comedy of manners?

AS: I don’t think my six months at Leeds Metropolitan affected me. I had a blast but I was drunk most of the time. However, I think I was steeped in British culture growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, because British sitcoms, TV series, were massive in Sweden. Everything from Monty Python to Blackadder and Fawlty Towers, everyone watched them, and we only had two public-owned channels, TV1 and TV2, so at least half the population would watch them. British comedy had a big influence on me growing up, and British culture in general. On Friday night you’d sit and watch British comedy shows and then, Saturday afternoon, my dad and my uncle would watch the Premier League, so it was a lot of UK.

JS: [Referring to Galitzine] Does this happen often, where you run into people who have recently seen or worked with your family?

AS: Yeah, quite a bit. This festival tour we’ve been on has been wonderful because my dad is on the same circuit with Sentimental Value and it’s been such a treat because quite often we miss each other – “Dad was here two days ago, my brother’s coming in a couple of days.” But with this the guys can go to Cannes together, and Telluride, and London – it’s been a real treat.

JS: Was there a film festival where Pillion had the most rapturous reception?

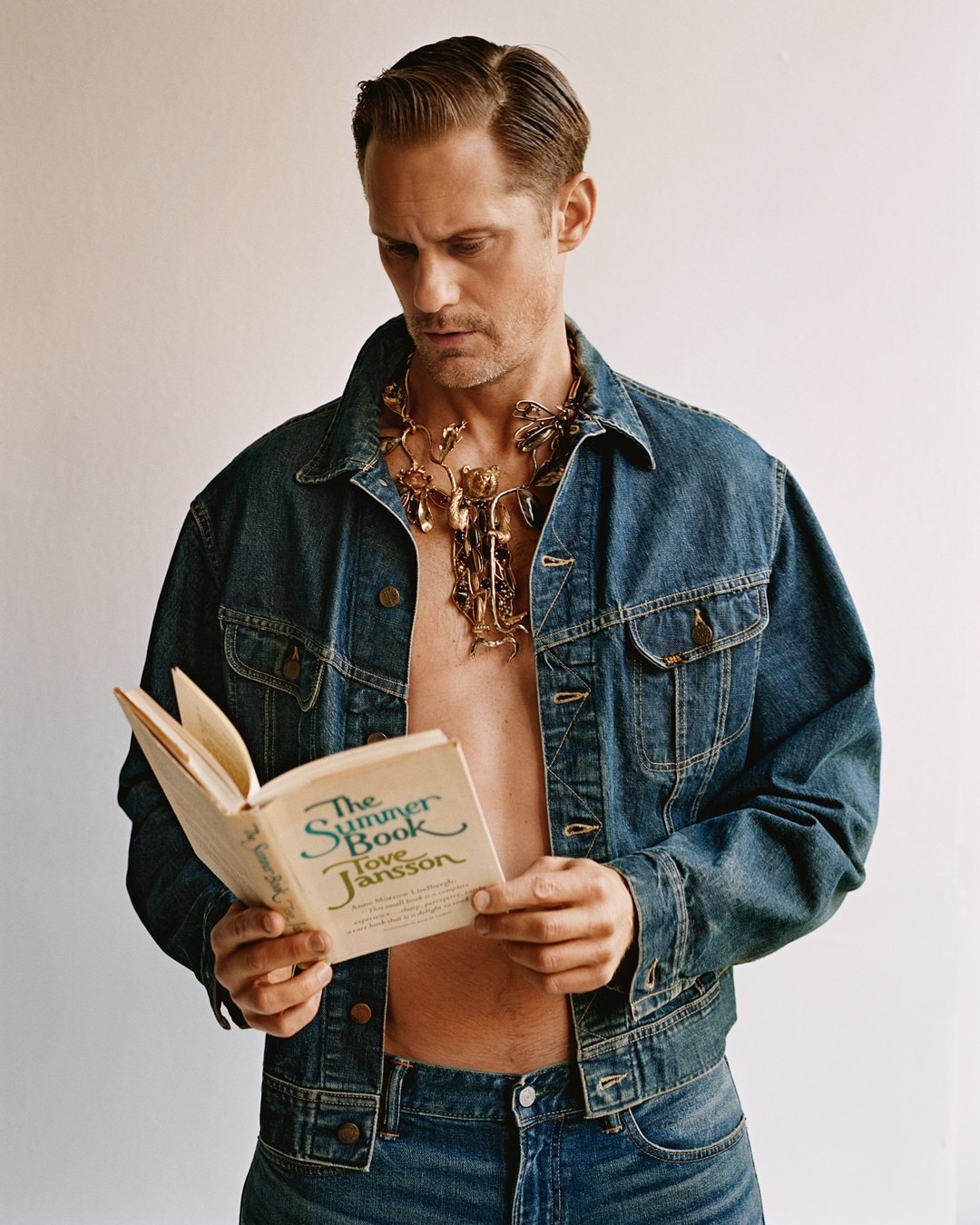

AS: I’m not on social media, so I don’t experience the aftermath of it, I have no idea. It’s all about having fun in the moment. I don’t dress as my character, I find that a bit too meta. I’m on the red carpet, I’m myself, but I’m dressed like Ray. It’s more being inspired by the tone of the movie and the people I made the movie with.

Once before when I did a movie [2015’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl], a bunch of the crew members were drag queens. We shot it in San Francisco and the premiere was going to be at the legendary Castro Theatre and the drag queens were hosting the after-party. Marielle Heller, who directed the film, and [Skarsgård’s co-star] Bel Powley were going to wear these extravagant outfits and I was sitting there in a suit, so fucking boring. So I asked if I could come in drag and the drag queens were like, “Yeah we’ll glam you up, who do you want to look like?” I said Farrah Fawcett and they gave me this amazing outfit. It was a blast. And I think on this tour, after having spent time with the guys from GBMCC and the London kink scene, them showing up with their masks and harnesses for filming, I don’t want it to feel like cosplay or a fucking actor going, “Hey, look at me in a harness.” But it also wouldn’t feel right to come in a boring grey suit. It’s been fun to be playful and somewhat inspired by these guys I worked with.

JS: The playful bit of the film is where I really fell in love with Ray – on their date, when they can be outside of their roles. How was it running through Bromley town centre?

AS: It was exhilarating. Partly because we couldn’t afford to close off Bromley High Street on a Friday afternoon, so it was fully open. The team had to get creative and hide cameras behind trees – they hid one in a rubbish bin to get those shots. And then Harry [Melling] and I, we were just thrown into it and had to interact with whatever happened around us. You never knew what was going to happen. I loved the fact that it was this heightened, Richard Curtis-rom-com trope of the falling-in-love montage. It was interesting to show a different side of Ray, a more playful side. I loved how it ended and the multiple potential interpretations of that ending. It’s been interesting at Q&As after screenings, talking to audiences about how they interpret it. It really runs the gamut, including, “Ray is sadistic and putting this together knowing that he’s going to leave.”

JS: Another interpretation is that Ray just couldn’t cope with the pain of knowing freedom. He can’t operate outside of being constrained by walls.

AS: I’ve heard that interpretation. But I’ve heard as well that he organised this and then lowered his guard for a couple of hours – and then he felt this intense connection to Colin and that scared the shit out of him. Potentially because of something that happened in his past, but he is letting someone in and being that vulnerable scared him enough to disappear. Another interpretation is that it’s almost an altruistic act. It’s Ray knowing they’re not compatible, knowing Colin wants something else – “Look, if I ask you, you’re going to say, ‘No, no, I’m happy sleeping on the floor seven days a week.’” By showing Colin, “This is what you want. And not every day, but maybe once a week, maybe once a month, you want this. I’m not the guy for that.” To help Colin get to the conclusion he does at the end of the movie where on his Grindr profile he says, “This is what I want: a day off.”

JS: And, “I won’t cut my hair.”

AS: I love that. I love it. I always dodge that question of what my interpretation is of Ray’s intentions in that moment, because people can have different interpretations. But I love the ending. I think it’s also so nice that Colin wasn’t like, “I dipped my toes into sub-dom and it wasn’t for me.”

JS: A more conventional film would have shown him married in a pastel shirt.

AS: “Now I’m happy with a husband and we’re in a very equal relationship, we share the workload and tidying up and we sleep in the same bed.” I love the fact that he’s still a sub. He loves it. But he’s forged his own path and he knows the extreme version that Ray wants wasn’t for him. He’s found his preferences.

WAITER ONE: Is everything OK for you?

AS: Maybe a little sandwich. How do you feel about that?

JS: I feel great about that. You lived in the US for a long time and recently moved back to Stockholm – how was that?

AS: I lived out there for 20 years, almost half my life. I started [having a] feeling, it was actually just before the pandemic. I got an apartment in Stockholm but I still lived in New York. [Previously] I was just crashing on my dad’s futon whenever I was in Stockholm, a few days here and there. But for the first time I could have a couple of weeks in Sweden. And I noticed how calming it was. I was the only one in the States. My parents, all my siblings, have always been based in Stockholm. I just felt my shoulders dropped a bit when I came home. But I loved living in New York, so for a couple of years I went back and forth, but around the pandemic it was just nicer being back home with the family. And then my roots started to attach themselves again to the soil where I was born and raised. A couple of my brothers started having kids and then the passage of time became more painful in a way. Before there were kids involved I’d be gone for six months and everything was the same when I came back. Now I was like, “Oh, my niece and my nephew don’t recognise me.” It was something about getting closer to them.

“A question I’ve been thinking about is, what type of projects, what kind of depictions of queer people in general do we want on screen and on television?” – Alexander Skarsgård

JS: What was it like growing up in your family?

AS: I think I was always eager to get out of there because it was a very noisy household and I was the eldest. There were always screaming kids around, and my parents, who I love, are eccentric bohemians. It was a big, extended family of stuff that I, as an adult, love but as a teenager found frustrating – these hippies, drinking red wine until the wee hours. I just wanted to get away, which kind of precipitated the move to the States to find my own path. Also, I didn’t want to be an actor as a teenager, probably also because I was adamant about doing my own thing.

JS: Do all Swedish people have to do military service [Skarsgård enlisted in the Swedish Navy’s SäkJakt unit when he was 19]? Or was this part of the escape?

AS:It was part of the escape. I’d say it was rebellion against my father, but that’s probably a stretch because I didn’t get much reaction out of him when I told him I had joined the military. He was just like, “All right, cool.”

JS: Are you recognised in Sweden?

AS: I grew up in an area called Södermalm in Stockholm and we rarely venture out of our little neighbourhood. My dad lives there, all my siblings live there, my childhood friends. It’s a radius of ten blocks and the people in that area, they’re probably more surprised that they don’t have a Skarsgård on the street. We go to the same bars and restaurants, so it’s not like anyone is surprised to see us. I can be … I don’t know if “private” is the right word.

JS: Before we go, I have to ask – the penis isn’t real, is it?

AS: The Prince Albert? [Skarsgård eats a tiny sandwich and says nothing.]

JS: Maybe a more difficult question – do you think there’s any tension around the issue of straight people playing gay people?

AS: I obviously don’t think it’s a problem because I wouldn’t have taken on the job. In terms of lived experience, it’s an interesting question, but it’s also tricky because, to me, the most important question is what type of projects do you want to be part of, what type of projects do you want to send out into the world? What type of projects do you want younger people to see when they see a depiction of any subculture? I was excited about Pillion when I read it because it felt very truthful and authentic to the subculture, but also very accessible to people who are not in that subculture. And the fact that Harry [Lighton] didn’t sugar-coat it – “Look how amazing they are. They’re just like us.” He allowed it to be awkward and weird, and that excited me.

A question I’ve been thinking about is, what type of projects, what kind of depictions of queer people in general do we want on screen and on television? And is there a diversity in the stories that are told? Are some scary, or funny, or awkward? Is there room for a movie like Pillion out there? I felt strongly that, yes, there was. It excited me because I felt like this was a depiction I hadn’t seen before. But then the question of who has the right to tell this story is a difficult one, because do the writer and director have to have a personal lived experience of not only being gay but also of having been in a sub-dom relationship? Do all the actors have to have personal experience? Because I have gay friends who know absolutely nothing about sub-dom culture – would they be qualified to play Ray just by virtue of them sleeping with men, or would it have to be someone who also has experience in the sub-dom community? It’s only something I thought about and discussed with Harry Lighton when we first started this. What do you think?

JS: I imagine, being a gay actor, it would be annoying to only be asked to play gay roles. I haven’t tried it, but I imagine, as an actor, the whole point is acting. Otherwise you’re just living.

AS: It’s also not always a binary question of whether you sleep with men or women – and this is not me saying that I’m bisexual – but it’s also great that we’re living in a time when more people feel comfortable shouting out what their sexual preferences are. I also think if you choose to be private about it, that’s also your prerogative. I think it’s sometimes good to put less focus on the actor and more on the character the actor is playing, rather than, “All right, show us a checklist of your past experiences and let’s see if you qualify for this role.”

I have gay actor friends who are privately open but don’t feel the need or desire to publicly talk about it. And I don’t want to force anyone to do that. So I think it would be beneficial to open up the types of stories that can be told about different subcultures, to take some focus off the actors portraying these characters and focus more on the depiction of that subculture. Does it feel authentic and shown in a way that is informative and interesting in the world? [Eats the last finger sandwich.]

JS: I feel like we’re in a competition.

AS: And I’m winning.

Casting: Greg Krelenstein. Hair: Anthony Turner at Jolly Collective. Make-up: Mel Arter at Julian Watson Agency using DERMALOGICA. Set design: Andy Hillman at Streeters. Photographic assistants: Lex Kembery, Jess Pearson and Simon Mackinlay. Styling assistants: Vincent Pons, Natham Fox and Dominik Radomski. Hair assistant: John Allan. Set build: Dean Coombs. Set-design assistant: Charlie Fairs. Set build: Dean Coombs. Processing: Bayeux. Production: Partner Films. Producer: Fernanda Dugdale. Production coordinator: Star Santos Hannan. Production assistant: Nikodem Postaremczak. Post-production: Output

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2026 issue, marking 25 years of AnOther Magazine, on sale internationally on 12 March 2026.