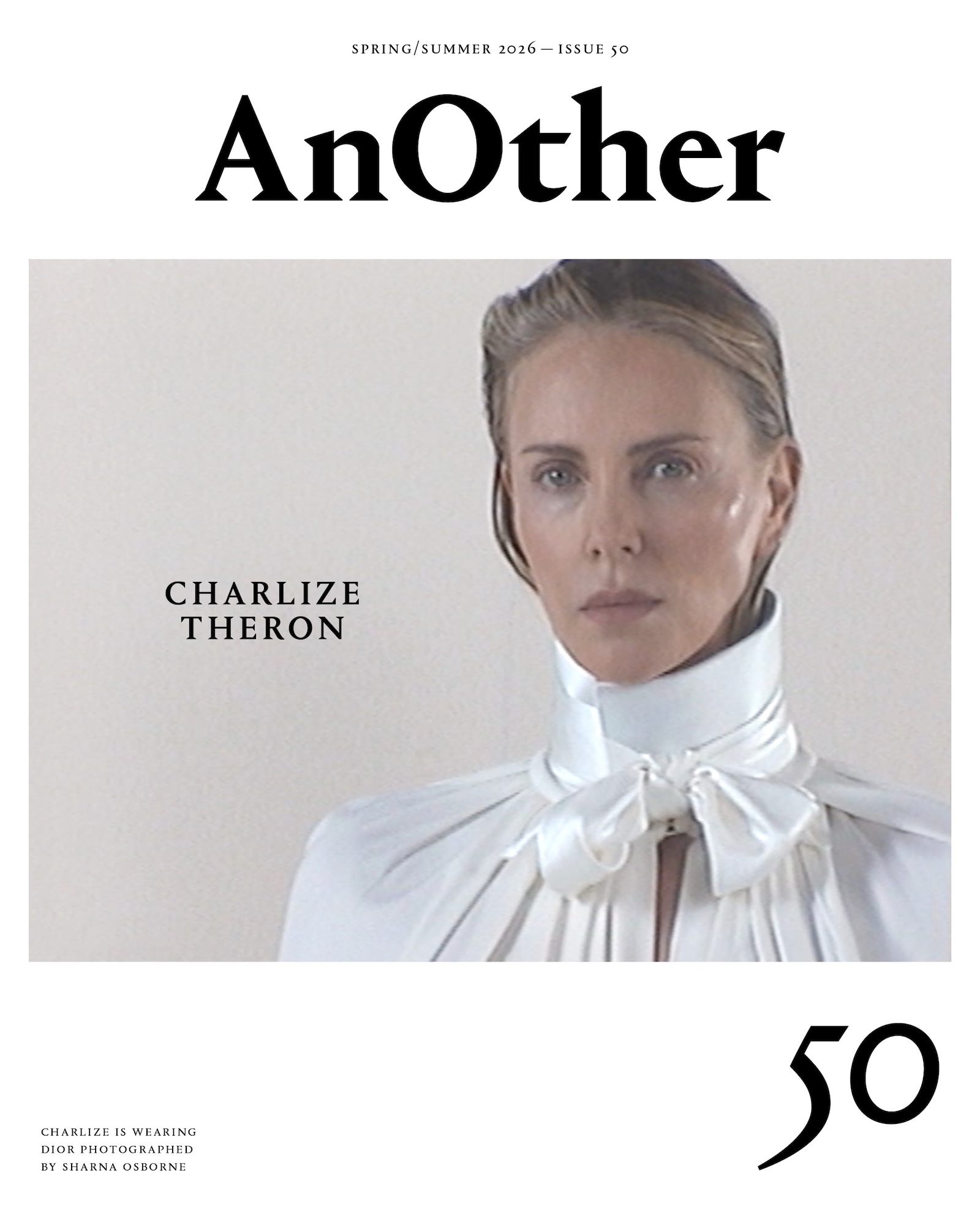

This story is taken from the Spring/Summer 2026 issue of AnOther Magazine:

A breathless profile of the actor and producer Charlize Theron once defined her career, then 20-odd years established, as “pure stardust”. I beg to differ. The better metaphor is the climb.

Theron is sipping kombucha. The ostensible reason for our conversation, via video call this winter afternoon, is to discuss 2026. In the film Apex the Academy Award-winning actor will play Sasha, a rock climber who is menaced, in the badlands of Australia, by two unrelenting forces: the wily hunter character (Taron Egerton) and her own enormous grief. Sasha is a modern woman: stubborn, powerful, individualistic, solitary. She is a variant of the characters that Theron has found herself drawn to in this phase of her career, women exacting their power through their physicality, carving out complex identities and desires outside the gendered villain/hero binary.

From her early years in South Africa, Theron always knew that she wanted to be a storyteller. Acting became the vessel for that attraction to narrative. At the age of 28 she won an Academy Award for her psychologically alert portrayal of the serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Patty Jenkins’s film Monster. In some ways that performance is the urtext of Theron’s career, the masterpiece expression of her ability to camouflage her own natural glamour and inhabit the minds of others. There isn’t a genre or a tone that she isn’t willing to approach, from cameos in Arrested Development and The Studio to scene-eating in Mad Max: Fury Road and The Old Guard. She is an ambassador for the sort of immersive acting that is increasingly endangered in the age of stunt casting. Here we discuss Theron’s formative years in Nineties Hollywood, her decision to start producing, the action-film genre, skittish financiers, motherhood, AI and dictatorial photographers. Theron is a voluble speaker. She doesn’t mince words. She is also very funny.

DOREEN ST FÉLIX: I first watched Monster at a very young age. I remember your performance stirring feelings in me that I did not have the language to articulate yet, feelings about women and the terror and power of agency. Did I understand what acting was at the time? No. Later, as I learnt and became obsessed with actors, I learnt about your life, your move from South Africa to Los Angeles. What was it like for you, that jump? Was there a moment when you realised you were at risk of assimilation – of permanently leaving where you came from?

CHARLIZE THERON: I completely relate to not knowing actors were actors. I truly believed Daryl Hannah [in Splash] was a mermaid. I grew up in a very, very small town – tiny. And we had a video store. I remember being about six when it opened and I had just gotten a BMX bike. I would take my BMX and I would go rent movies. My mom got a Beta machine and that’s when my life changed, because we didn’t have a lot of television. We had a few hours a day and I got very few American shows – a few sitcoms and soap operas. We also had a drive-in theatre. My mom loved watching movies, she really loved doing that with me.

DSF: What were some of the films you watched with her?

CT: I watched Die Hard. I watched Fatal Attraction at a drive-in with my mom.

DSF: Wow, Fatal Attraction?

“I think back to moments I had on sets or with directors or auditions, stuff you would just never get away with [now]” – Charlize Theron

CT: It was a long way to drive, so my mom was like, “We’re not turning back. We’re going to watch this movie and we’re going to make this a lesson.” I loved disappearing into worlds. I was a weird kid. I was ten years old and I loved Kramer vs Kramer. In South Africa we had an industry but I didn’t know anything about it. We didn’t have magazines that wrote about it. We had one magazine that was written in English and Afrikaans, maybe two – but the one that circulated in our household had stories about people who found giant snakes in their backyard. It was never really about the entertainment business. All of this stuff has really changed. I’m a dinosaur.

DSF: You’re not a dinosaur.

CT: But it’s a whole different world now. The concept of art was exposed to me because of my mom on every level. Whether it was going to the ballet, or to the opera, my mom loved narrative. She would listen to stories on the radio every afternoon. When I came back from school she’d make me lunch and she’d be sewing an outfit, and we would listen to the radio and I’d fall asleep to these narratives. Her exposing me to storytelling at a very young age ignited this love for it. I just never knew that you could make a living from it. When I started dance, it took me years to figure out that what I loved about dance was the storytelling. In my immature brain, I was like, I love dance, I love ballet. But what I loved was the disappearing, like watching a movie and disappearing and having access to losing yourself.

DSF: Isn’t there something very submissive about the role of the actor, willing yourself to submit to the scene?

CT: I think there is definitely a version of having to submit, trusting the people that you’re making a movie with. I’ve made movies where I don’t and it’s very hard. But more than submitting, what I always aim for is this thing you find in sports, in dance – they call it “the flow” – where you’ve done the work, you’ve spent enough time with it, and hopefully on the day you’re doing it, you’re just in the flow. I love chasing that feeling. Trying to understand a human is a complex thing and you’re constantly discovering.

DSF: Are there characters you’ve struggled to reach flow state with?

CT: Yeah, for sure. [Laughs.] You struggle a lot more than you win. Monster personifies that for me. I really felt like Patty Jenkins and I worked so well together. We were one unit. And we spent a lot of time in Aileen’s world, with all of her letters over ten years of being on death row, with people who knew her.

DSF: People she knew were open to that?

CT: There was one woman, Dawn Botkins, her best friend from childhood. She was the one that was with her when she was executed. She really loved her, and she was tough and direct – she didn’t want us to feel sorry for Aileen, she wanted us to be truthful. And Nick Broomfield was making two documentaries about her. He was kind enough to share footage and talk with me because he spent a lot of time with her. She was executed two days after I said yes to the movie.

DSF: Do you remember how you were feeling that day?

CT: I mean, I hadn’t started to work. Patty was talking me into doing it. I was like, “You have the wrong girl.” From watching Nick’s documentary, she was so specific that if you were going to tell the story, you had to obey by that, whether it was dialect or teeth or body language. All of it was an eye-opening experience. You don’t always get that on a movie. Sometimes I’ve done favours for friends and I’m like, “I love you, I’m doing this for you, but I don’t connect to this world.”

DSF: Your Hollywood career is three decades long, a feat in any world, but especially that fickle one. What’s the horizon view on what has changed since first moving to LA?

CT: I think back to moments I had on sets or with directors or auditions, stuff you would just never get away with [now]. And prior to that, being a model. I told my daughters the other day about a job I had – I remember this photographer yelling at me, verbally abusing me for like 15 hours on a shoot, and just not feeling human. It still happens. I recently worked with a photographer who would aggressively walk up to me and put his hands on me, tying my shirt. I had to say something. The broad strokes are that it’s so incremental. I think that’s the most frustrating thing about it for women. It’s four steps forward and 20 steps back, but we’ve come a long way since I started, for sure. You had to squeeze your way in. And really the only way to get in there was to be the trophy, sexy person. The alternative for me was to go back to South Africa and I didn’t know what I was going to do. My parents had a road-construction company. Was I really going to do that? I was so driven by wanting to do something in the arts. For me, there was a real focus on how can I go about this so I have longevity? I saw it around me, girls working, they do three movies and they just …

DSF: They were disposable.

CT: Exactly. It came from this place of survival, where I was like, whatever I do, I better be smart about this. I have to surprise people and make them go, “Wait a second, there’s more here.” I was lucky enough to get an agent who was like, “No you’re not doing that. I want to introduce you to this filmmaker.”

DSF: It seems to me it was very important for you to start producing when you did.

CT: Very much so. When I started producing 25 years ago, no one took actors seriously. They got a credit, they got some money. But I was fascinated by the actual job of producing. The nuts and bolts of putting a movie together. I was so interested in hanging out with the crew. I was not that kind of actor who would go to their trailer, disappear and come back. I’m still not that actor. I hate trailers.

DSF: You want to know what the best boy is doing.

CT: I’m a grown-ass woman. I do want a little bit of control over my own destiny in the art that I make. Even when it’s considered an “action movie”, I’m invested. I wish sometimes I wasn’t as invested because it can make it hard. It can almost become personal. And so there are two parts that even me out. There’s the actor who is very open, sensitive and can be very vulnerable. Then there’s the producer who can see the film from 30,000 feet in the sky and protects the actor in me. When I think of things that would have happened to a lot of movies that I was in if I hadn’t produced … You have to have the right director who not only wants to make a great movie but understands that you have to have great actors. They shouldn’t just be there to carry the plot. Right now, attention spans are tapping out. We’re chasing this dragon. You need good actors. You need good scenes. You need good editing. You need breaths. You need space. You need to push the envelope.

DSF: Across all traditional media, the instinct is to be on the back foot. We cater to the idea that attention spans are shot and cater to it defensively. But there’s an alternative response. People are willing to sit in theatres and watch long movies. Look at the award slate this year.

“I’m a grown-ass woman. I do want a little bit of control over my own destiny in the art that I make” – Charlize Theron

CT: Twenty-year-olds went to see Oppenheimer. We’re going to stop making art. We’re just going to commercialise the fuck out of telling stories. My argument is always that we can make movies that make people feel uncomfortable. That can be a good thing.

DSF: There are emotions that are undervalued in American culture that are important to feel. Discomfort, disgust. You sometimes lean into what is called “unlikeability” in your roles and that is exciting to see. Are you thinking about this when you play a disgruntled prom queen in Young Adult, or playing Megyn Kelly, someone that people have very strong feelings about, in Bombshell?

CT: It’s interesting that you bring those two movies up because they’re examples of great partnerships. Jason Reitman, with Young Adult, we never had any conversations about whether she’s likeable or unlikeable. We talked about, “Who is this stunted person, who pretends to have grown up but is in arrested development?” [The screenwriter] Diablo Cody writes in such an honest way. When you read it, you go, “Fuck, there’s a bit of Mavis in me.” People saw themselves in her and some didn’t want to admit it. But it’s OK not to be perfect. It’s OK not to fall in love in the third act and skip down the street. A character like Mavis could have had the trope of, “This girl changes. She learns this big lesson at the end.” But Jason and Diablo were like, “What if she doesn’t?”

DSF: Most people don’t change.

CT: Yeah, and it’s rare to see that in movies. There’s always this thing people would say – “They’re not going to like you.” My skin would crawl. Even with Aileen in Monster, the financier called me when he saw the dailies and he was like, “You never smile. You look so angry and mad and no one is going to like you.” He was obsessed with me not smiling. I have a real reaction to that, the idea that you won’t like me if I’m truthful, if I come with my warts and all.

DSF: When you were making Monster, people dropped out, right? The movie almost skipped theatres and went to VHS. A kind of ghettoising.

CT: On that one, yes. And also, by the way, on Bombshell. Our financier pulled out six weeks before [filming began]. Maybe it was less. I’m so traumatised by that experience.

DSF: And this is in 2018, the age when feminist inquiry and critique of sexist institutions were popularised all over.

CT: And I didn’t want to make a movie that was judgemental. It wasn’t a Megyn Kelly story. It was a story about something horrible that took place in an organisation. That was just the beginning of the end, what happened at Fox with Roger Ailes. I think people automatically assumed it was going to be some terrible rendition of how much we hate Republican women. That’s not what it was. That is such low-hanging fruit.

DSF: Right. At the time I feel like, in the liberal sphere, you could gain so many bona fides by just beating down on conservative white women. It’s kind of like so much of the Real Housewives franchise was about satirising women who were excessive, but what happened was that the show ended up being very smart. I’m a huge Housewives person. I think you might be too.

CT: It’s human behaviour, because they can’t keep it up, right? Again, you have to watch some of them with their warts and all, and it’s some of the best acting observation you can have. A lot of the time I watch it I’m like, wow, I need to remember that for a movie. I grew up watching women have rage, whether it was my mom or on Dynasty or Dallas. And I think that there is more access now to seeing women having multiple emotions – the complexities of how we function and the different gears we can have. I thought that when you get upset, you take your drink and throw it against the wall. That was my blueprint, watching Sue Ellen on Dallas throwing her drink and dressed gorgeously in a sequined top.

I feel like the only honesty that I saw with that was through my mom. My mom had a complex relationship with my father, and I think it really informed me. Obviously, when I was younger, I had no concept of how complicated people and relationships are. And of course I wish that she had a wonderful marriage and didn’t have to experience all of that. But I do think that in many ways it made me as an actor be more honest in portraying women. I have had great opportunities to play moms – conflicted moms. I remember working with the director Niki Caro [on the 2005 film North Country]. It was the first time I played a mother with a teenage son, and I talked a lot with Niki about when parents don’t have the luxury of having nannies and you’re trying to survive every single day – you’re going to have a short fuse and not always say the right thing. You’re going to do things that you might regret. Those were the things that we showcased in that movie. I think good artists can have empathy for the circumstances of others.

DSF: My generation, millennials, found a lot of comfort in black and white binaries – it can become a coping mechanism. But what about human behaviour?

CT: I think that’s interesting, the generation that’s raising the Alphas. I see it in my own kids. There’s a part of it that is so wonderful because you see agency, a young girl saying what she feels. But then I have moments where they’re complaining and I’m like, “Buck up.” Both my girls are so smart. I have a ten-year-old and a 14-year-old. So it’s three women living in a house.

DSF: A house of women.

CT: And they’re at this age. These are the qualities that are going to make them fucking ballers, but they’re also the qualities that are going to send me to an early grave. [Laughs.]

DSF: I want to know about your transition coming out with films after Covid shuttered the industry. The Old Guard, the sequel to it, Apex and Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey, out this summer.

CT: In all industries we’re struggling to recover. There was a lot that happened that you just don’t bounce back from. I feel like my attitude is proactive. I don’t want to sit and mourn what we lost. I’d rather look to the future. There are changes to our industry where a lot of bodies will just not be needed because of AI, where the movie-going experience will probably not exist in theatres any more. We can get very dark about this stuff. But I want to believe that you don’t have to throw out the baby with the bathwater.

“There is more access now to seeing women having multiple emotions – the complexities of how we function and the different gears we can have” – Charlize Theron

DSF: So, finding opportunities to negotiate with the encroachment?

CT: Finding reasonable people to reason with. We’re at the 11th hour. Our footing is a little bit off. We made Apex as a lot was going on in the industry. The script was really solid and the rewrites we developed as we were making it. The director was right for this – Baltasar [Kormákur] was able to create a wild, exciting, suspenseful film while always honouring the story and the characters. And Taron Egerton is in the top five actors I’ve ever worked with. This was my best experience making a movie.

DSF: The action film is ultra-American, tied to essential myths about masculinity and heroism. So you taking up the masculinised mantle, it’s a critical chapter in film. The action films you do aren’t just gender flips.

CT: That’s a lot of pressure.

DSF: You can live up to it! But I had these moments watching Apex where I’m so aware of the trials you put your body through. The expanse, the water, the caves. It’s like no civilisation exists except the one for you and Egerton’s character.

CT: It’s very immersive. Some of the locations were places that no one has shot in. None of it is CGI. It was just hikes down a crevasse, into a gorge, and then shooting all day and then hiking the equipment all the way back out and doing it again the next day. And people doing it with joy in their heart because we had a director who really shepherded us. It was like a high. This incredible woman taught me how to climb. Very few movies get made like this any more.

I tapped out one day before wrap. I have never done that. I handed my physical body over to it willingly because that was the story. I had torn intercostal muscles, I got a middle-ear infection from the water. I was just exhausted. I remember going to my trailer one night and I thought I was going insane because there was so much water in my ear. I took a pretty bad pull in my elbow – there’s this big nerve that runs across your elbow that kind of popped – I had it happen on my other one three years ago, so I knew what it was and I knew I was going to have to have surgery for this. I laid it all out on that ice, left it all on the field.

DSF: The body has its limits. Have there been more existential moments where you’ve thought, at some point I may have to pull back from action work?

CT: I’m not going to be able to stop this process called ageing. But I am also very aware that we have access to great things we never had three decades ago. Like when my grandmother was about 52, I remember I was like, oh, that’s what grandmas looks like. The little curlers and the muu-muu. I’m not scared of ageing. I just want mobility for as long as I can possibly have it. I want to be able to feel strong for as long as I possibly can. My mom is 74 and she hikes every morning. The other day she lifted a 78-pound dog into the back of her car like it was nothing. I’m like, OK, I really lucked out with genetics. And I also love that she’s at two knee replacements. So part of me is like, yeah, I have a surgery after every movie but that’s just making me stronger. I’m going to be bionic by the end of it.

Casting: Greg Krelenstein. Hair: Adir Abergel at A-Frame using VIRTUE LABS. Make-up and skincare: DIOR BEAUTY. Manicure: Zola Ganzorigt at The Wall Group. Set design: Carter McNeil. Photographic assistants: Steve Yang and Essence Moseley. Styling assistant: Sierra Estep. Tailor: Mari Margarian. Manicure assistant: Mandy Enkh. Set-design assistant: Levi Gould. Production: PENNY. Executive producer: Kalena Yiaueki. Head of Creative Production: Anastasia Soloveiva. Production Coordinator: Ellen Kozarits. Production assistant: Lily Cordingley. Post-production: Vrinda Jelinek

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2026 issue, marking 25 years of AnOther Magazine, on sale internationally on 12 March 2026.