Lots of designers talk about their woman – sometimes women – with earnest knowledge. Her life, her loves, her wants and needs. But you wonder how many of them actually head out and meet her. That was something Rachel Scott did early, when she took over as creative director at Proenza Schouler last autumn. She held a dinner and invited several women, including three art advisors, a writer and a retired lawyer, to get under their skin. Or rather, inside their clothes. And then she set out to make them.

Less than 24 hours before her debut show for Autumn/Winter 2026, Scott is pulled in many directions – which is understandable, given that she is the only designer to stage two catwalk shows within a single fashion week. Her own Diotima collection will be unveiled on Sunday; its studio is three streets from her headquarters at Proenza, as the brand is often abbreviated. But today, Scott is still thinking about the Proenza Schouler woman. “I always felt like I couldn’t get to her,” Scott says. She’s talking of the metaphorical and somewhat nebulous ideal of who the Proenza Schouler woman was in the past. “Like, there was this glass between me and her. And with that also, there was a level of perfection that I would see in her. I just find that level of perfection imprisoning,” she pauses. “Take the glass away. Let’s really get close to her.”

Women have always been important to Proenza Schouler – and not just because they were the ones buying their tailoring and hardware-laden bags. Although it was founded by two guys, Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, who left the brand last spring to become creative directors of Loewe, its name comes from their mothers’ maiden names. And its focus on craft, arguably, exalted tactile and traditionally feminine art forms like crochet, embroidery and knitting. All are dear to Scott, too – one of many reasons she got the job. In Scott’s Diotima line, that also chimes with championing female workers in Jamaica, where she was born and where she still works with craftswomen today. At Proenza Schouler, craft could take multiple forms – one print was composed of an image of orchids, a feminist emblem of the collection, scanned, digitised, re-photographed and scanned again. But the resulting graphic was also hand-painted onto leather, to skew it in the total opposite direction.

Talking of copying and recopying is kind of endemic when a designer is challenged to revive a pre-existing house – the idea is to take stuff from the past and redo it. Changed enough to feel new, but not so much you can’t recognise its source material. That’s all tied up with the notion of heritage, which interests Scott. But, as Proenza is only 24 years old, it’s something of a perverse notion. “I’m such a shit-stirrer,” Scott allows, laughing. “If there’s no heritage, what is heritage?” She means “heritage” in quotation marks – meaning fabrics like donegal tweed, here woven with a bright fluoro-orange backing and shaped into sculpted tailoring (also proposed in aged denim), to traditionally-constructed Italian shoes with welt soles, and to houndstooth checks, albeit woven in chiné silk to look watery and warped.

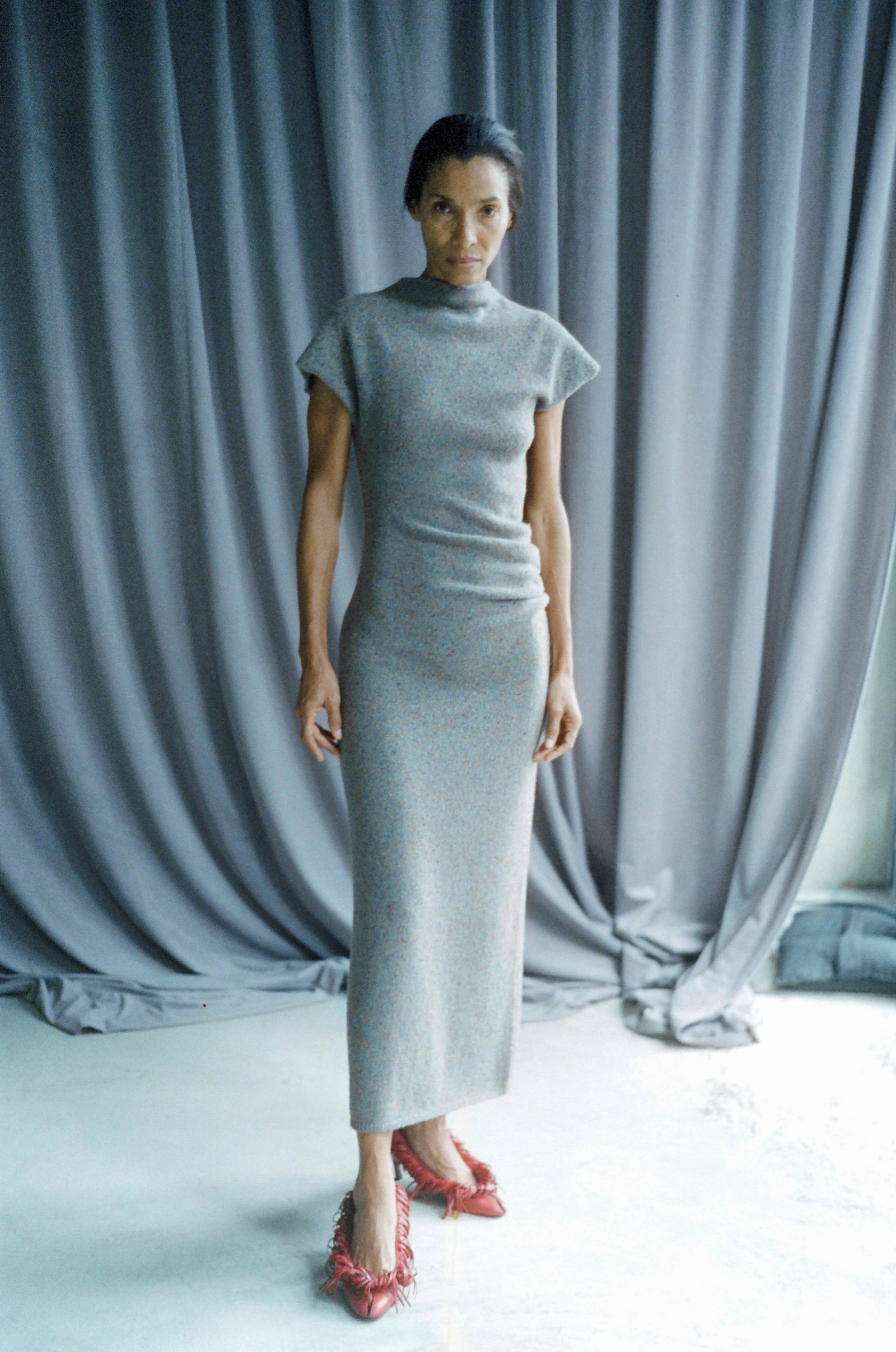

Warped was an idea. “A little off-kilter, a little haphazard,” Scott said. “Something as simple as: she put her dress on but didn’t smooth it down properly. A button placket that isn’t in the right spot … this mash-up of gathering, pulling, the buttons are mis-buttoned. Everything is a little bit off.” So that accounted, the next day, for necklines yanked off the body, clothes draped and bunched, and shifting as models walked – building up, up, up to a finale of dresses of splayed print, patched fringe and metal grommets. You could tick off the Proenza collections that inspired many of those, but at the same time, they didn’t look quite the same. Which was precisely the challenge, met.