“Fashion shows are about showing ideas.” Jonathan Anderson knows what he’s doing at Dior. When he talks like that about ideas – as he did backstage, about six hours before his sophomore menswear show for Autumn/Winter 2026 – he doesn’t just mean ideas of clothes, ideas within clothes, but ideas in a wider sense. Ideas of how we can be, who we can be, ideas of the forms creativity can take in a 21st century whose breathtaking technological evolution is genuinely upending the way the human mind works. And, of course, ideas of Dior, an unassailable French bastion. Then again, they said that about the Bastille, before 1789.

Anderson staged this Dior show on the 121st anniversary of its founder’s birth, which may be kismet, or merely a satisfying scheduling coincidence. It is also the 80th anniversary of the house’s founding this December. Did either of those things hold Anderson back from pushing Dior somewhere brave and new? Absolutely not. Across the Seine from Anderson’s show venue, in the plush confines of Hôtel Le Bristol, the haute couture client Mouna Ayoub is selling ten-dozen of her Dior pieces, including John Galliano’s radical rethinking of the maison in the 1990s, designs that collide Edwardiana with the nobility of Africa, or that controversially tore Dior to shreds in imitation (Celebration? Parody?) of the unhoused. It’s early days – he hasn’t even shown his first haute couture collection yet – but you get the sense that Anderson’s tenure could be as radically transformative in the annals of the house as Galliano’s, and as creatively rich.

This collection was. The inspiration was the couturier Paul Poiret, who titled his autobiography King of Fashion (modest) and who Dior deeply admired, yet whose style could not, on face value, be any more different to his. Poiret adored hot, rich colour, exoticism, the sensuous movement of fabric across an unfettered figure – bar the legs, which he shackled with his ‘hobble’ skirts of 1908. Dior, by contrast, was known for structure, a certain stiffness to his taffetas and pleated wools, to an essential Frenchness, for Dior grey and the monochrome Tailleur Bar. He revived the Belle Époque styles that Poiret almost single-handedly obliterated. But walking down Avenue Montaigne, shoe-gazing, Anderson saw a plaque outside of Dior dedicated to Poiret. There was also a recent Musée des Arts Décoratifs exhibition devoted to him, subtitled “Fashion is a party.” And Anderson, an obsessive collector of antique and precious clothing, found a 1922 Poiret dress for sale. It all clicked. Hence the unusual collision of these equally revolutionary men. “The way in which I work is collecting experiences through the process,” Anderson said. “And filtering them in.”

The big difference? Unlike the global dominance of Dior, most won’t know Poiret from Adam. He died broke in 1944, this Ozymandias of fashion, his empire crumbled to lone and level sands. “A man cannot be Poiret and die in destitution,” wrote a now even-more obscure fashion designer, Lucien François. Alas, fashion was a cruel task-master then, and now (as if to prove the point, Poiret the house was recently revived. It failed). But for Anderson, Poiret was a jumping-off point for Dior, to talk about his obsession with a neo-aristocracy of dress, to explore rich figured lamé and ballooning cocoon silhouettes and to push to someplace new.

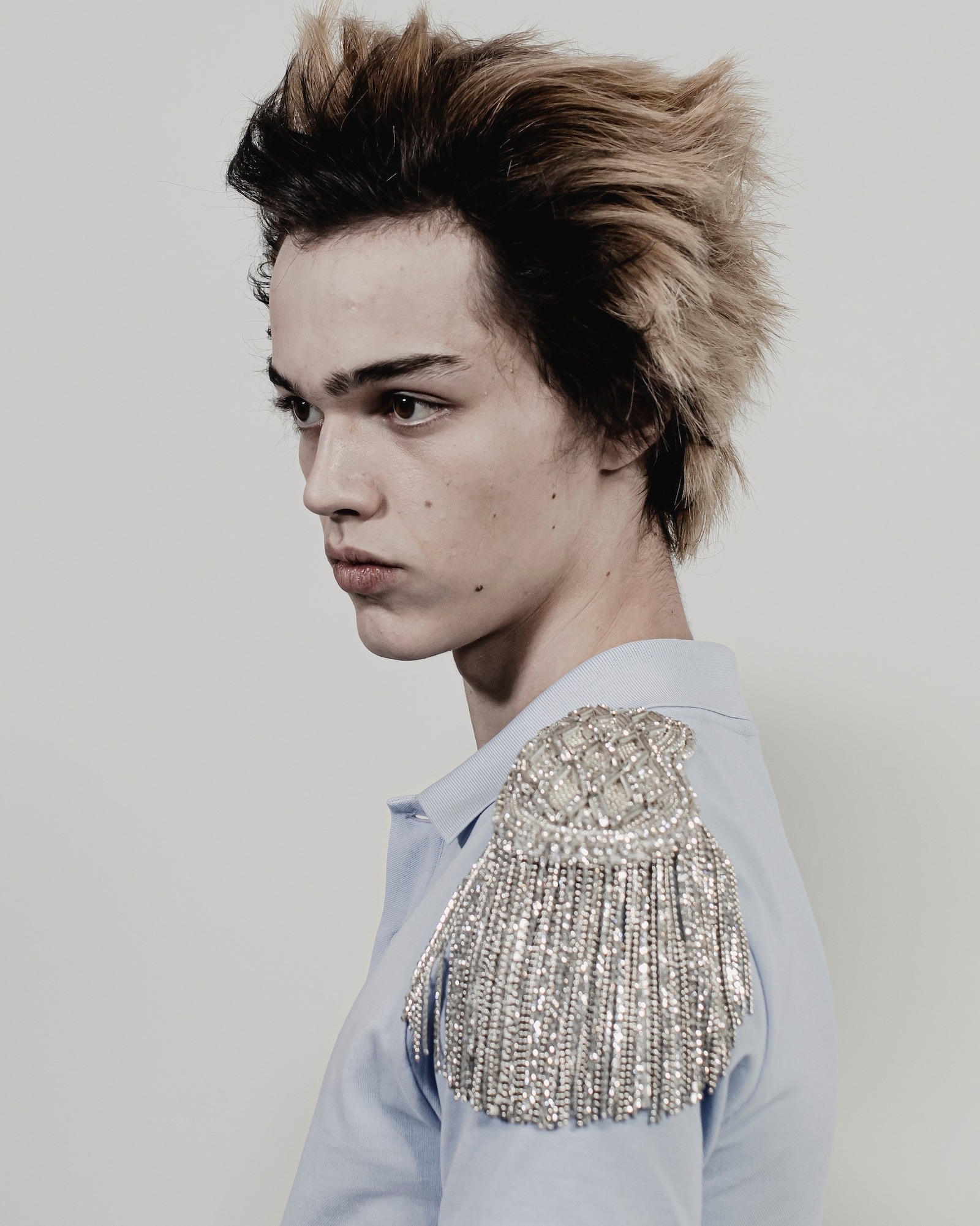

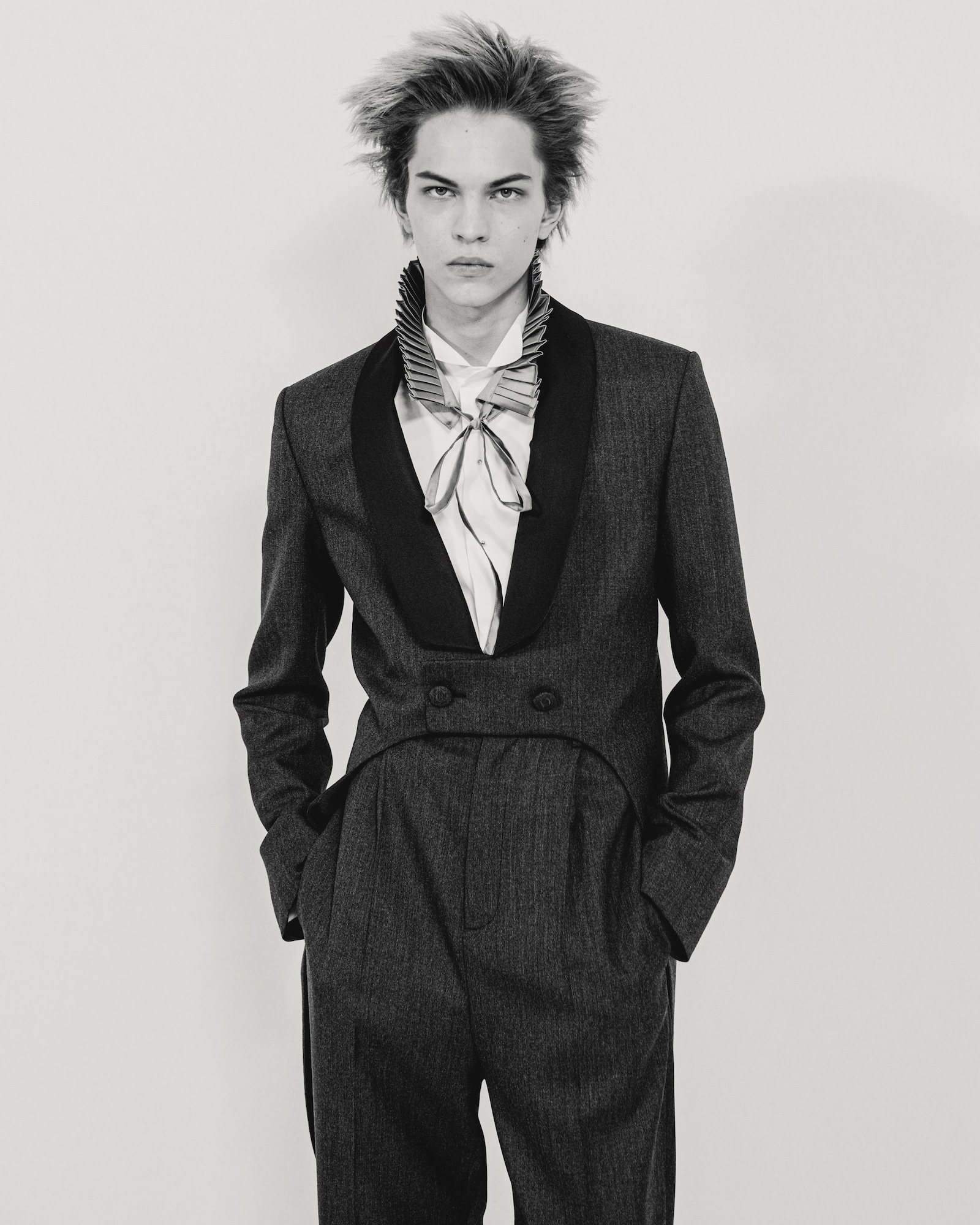

Poiret has haunted Dior’s corridors before – he was often present in John Galliano’s late 90s phantasmagoria – but here Anderson used him to shape a menswear collection that was a party, as well. The opening looks consisted of jeans topped with camisole tops that were, actually, cut-down versions of a “facsimile” of a Poiret gown, here mixed with a freshness that exploded time. Fabrics were woven by mills in Italy that had originally supplied the couturier, cut into slender trousers rather than drop-waisted dresses, square-cut tunics, or worked into the cocoon backs of trench coats and short, tucked-under capes snaggled with frogs and tassels. “Dior menswear is about tailoring,” Anderson asserted directly, and correctly. He proposed two different suits, one a bum-freezer mod style that nodded to the early 60s, the other looser, easier, with wide lapels, that originated in the early 40s. Before Dior, after Dior.

There was plenty of Dior here, an odd bedfellow with Poiret. But Anderson enjoys “wrongness” – his word – so his drop-waisted homages to dresses from a hundred years ago were shown alongside nip-waisted, pumped-hip jackets cropped high up the torso, transforming proportion in a play very much in the tradition of Monsieur. Some were elongated to sculpted, streamlined coats with a mid-century elegance – and, Anderson allows, women are buying these men’s iterations too. There’s no divide.

As for costume dressing? It isn’t restricted to Poiret balls, nor the saffron yellow wigs of the hairstylist Guido Palau. “We all do it, in different ways,” Anderson commented. What his Dior seemed about, ultimately, was that opportunity for reinvention – for him, for us, maybe most importantly for Dior. The space was hung with grey velvet, drapes that resembled the curtain about to rise on a theatrical production. Next week is haute couture. And the new look of that.