A monumental new exhibition in Vienna delves into the designer’s pioneering visual world, and his artistic collaborations with Jenny Holzer, Louise Bourgeois and Robert Mapplethorpe

In 2011, Helmut Lang – the Viennese-born, New York–based conceptual practitioner whose work reshaped fashion’s visual culture in the 1990s and early 2000s – entrusted the MAK with the largest public archive of his oeuvre. Comprising more than 10,000 artefacts, the archive encapsulates the disruptive, multidisciplinary practice through which Lang operated as a pioneering cultural architect from 1986 until 2005, when he left the fashion circuit to focus on sculpture.

Curated by Marlies Wirth, Helmut Lang Séance De Travail 1986–2005, reveals a selection of works (including some never published before) drawn from more than 800 artefacts in the Museum of Applied Arts Vienna’s holdings. Far from a conventional retrospective, the exhibition operates as a fluid thinking system – a “living archive”, in Lang’s own words.

Reflecting his work across Vienna, Paris and New York, the exhibition unfolds as a nuanced environment shaped by Lang’s site-specific approach to stores, runways, advertising campaigns and backstage moments. “It was never primarily about product or garments for sale,” Wirth says. “It was about identity constructed through space, artwork and cultural references.” The opening sections, ‘identity’ and ‘space’, establish this egalitarian logic across architecture, fashion presentation and image-making.

Central to the exhibition, and to its title, is the term Séance de Travail – “work session” or “work in progress” – which Lang adopted in the late 80s for his runway presentations. “He discarded the elevated runway and opted for more dynamic, performative shows,” Wirth explains, “with menswear and womenswear together, friends and unknown faces walking alongside the supermodels of the time.” Staged in industrial spaces and structured along intersecting paths, the shows were choreographed by Lang himself. “Instead of the classic walk–pose–turn–go back, it was like sitting in a Paris café and someone interesting passes on the street.” Models often carried their personal belongings, reinforcing the notion of clothing completed by the wearer. Lang’s casting prioritised character over standardised beauty, something Wirth describes as “always in progress.”

This sensibility materialises in the Séance de Travail room, where more than eight hours of runway footage are projected at monumental scale above a reconstructed show layout mapped across the floor. A sculptural grouping of original runway chairs anchors the space, collapsing distinctions between performance, archive and artwork. Later, a separate media installation immerses viewers in hundreds of stacked screens showing backstage moments, interviews and runway footage – a restless extension of Lang’s process-driven visual world.

Lang’s long-term artistic collaborations form another crucial strand. As Wirth recounts, Lang and Jenny Holzer first collaborated for the Florence Biennale in 1996, where Holzer projected Arno, a text work containing lines such as “I smell you on my skin” and “I walk through the room. I scan you. I tease you”. These were, she says, “emotionally and sensorially charged words that evoke atmospheres of smell and memory.” Lang created a conceptual scent for the pavilion that evoked human presence: a freshly ironed shirt, cigarette smoke in the night air. “From then on,” Wirth notes, “their relationship was based on mutual respect and a close friendship.” Holzer’s works appeared throughout Lang’s flagship stores; she even accepted his CFDA award in 1997, giving, Wirth says, “a very personal speech about him and their collaboration”.

With Louise Bourgeois, the exchange took a different form. “He incorporated her sculptures into the store architecture, used her voice in a Séance de Travail soundtrack, and recreated a 1948 choker of hers as a piece in a 2003 collection,” says Wirth. Bourgeois’s spider sculpture once stood in Lang’s made-to-measure studio on Greene Street. “These are deep, long-term collaborations, not surface-level branding.”

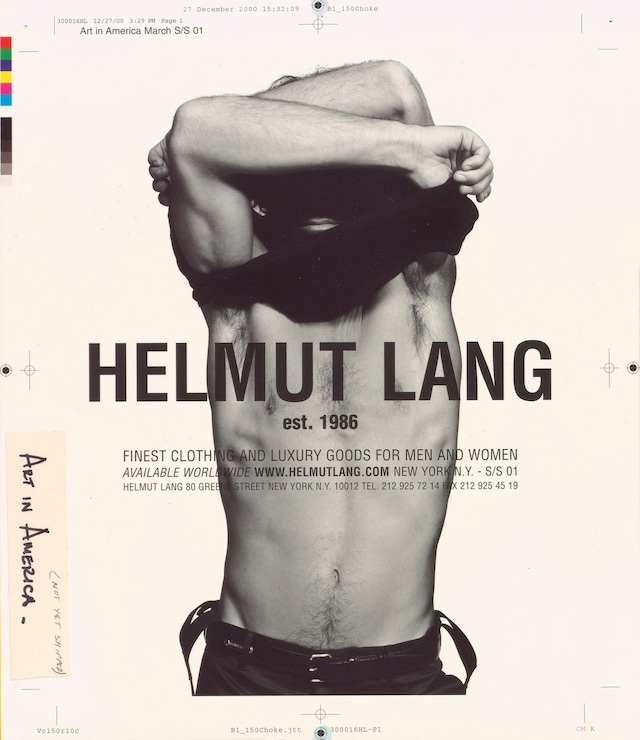

Lang’s advertising innovations appear in another section. The original Helvetica taxi-top advertisement that circulated across New York in 1998 appears alongside Robert Mapplethorpe’s ready-made photographs for the Barneys campaign. Lang sent coded signals through these images, using art historical cues and photography by Mapplethorpe and David Sims “to communicate an attitude decipherable only to those attuned to it,” says Wirth. He was also the first designer to publish campaigns in unexpected outlets – The New York Times, Artforum, even National Geographic – reaching audiences far outside fashion’s traditional circuits. His early digital experiments were equally radical: Lang launched one of the first designer websites and circulated CD-ROMs of a pre-recorded runway for private online viewing. “Technology was [only] just entering daily life,” Wirth says. “Lang used it strategically.”

Reconstructed modules inspired by architect Richard Gluckman translate the atmosphere of Lang’s stores into the museum setting, echoing the sculptural sensibilities of Richard Serra. “It’s not about recreating the stores,” Wirth explains, “but translating their atmosphere and making it immersive.” Veering away from the common misinterpretation of Lang’s work as minimalist, Wirth clarifies that the more precise term is essentialism. “He reduces things, not entirely stripping away ornament or embellishment, but paring down to what is essential, often rooted in utility and pragmatism.”

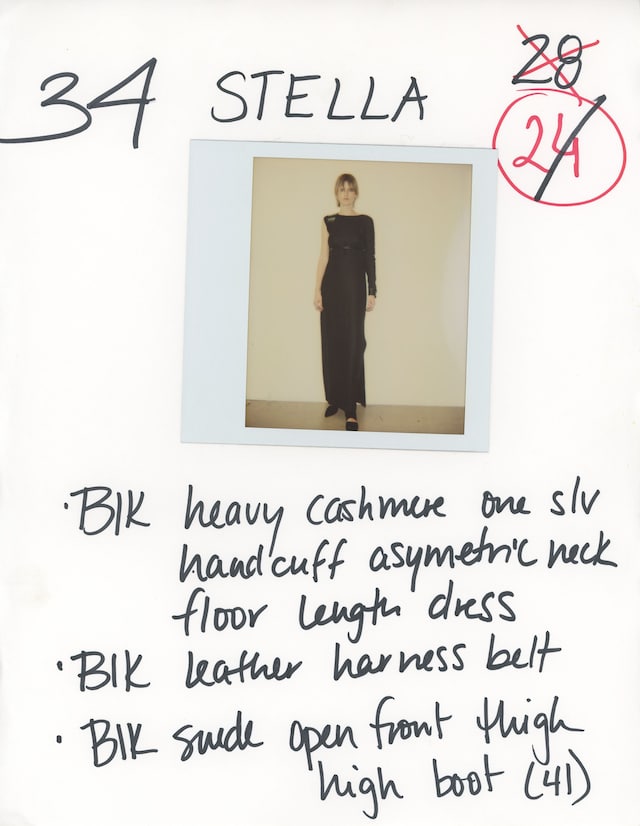

The final section ‘backstage’ reveals Trachten-inspired pieces, stingray leather, rows of Polaroids and press clippings that foreground the emotional and physical labour behind the brand. “Clothes are an adaptive surface,” says Wirth. “They shouldn’t define you. You are the identity, the clothes adapt.” Lang’s work resonated with a generation “too intellectual or too cool” for the rigid codes of the 80s. As Wirth puts it, he “defied those tropes: the image of what a woman should wear, how a man should behave”. Ultimately, the exhibition makes clear that Lang’s real legacy is a mindset that stays in motion, attuned to the present, willing to tilt the axis when the world grows rigid. Adapt relentlessly, subvert when necessary, and, as Lang urged, “find your own voice”.

Helmut Lang Séance De Travail 1986–2005 is on show at the Museum of Applied Arts Vienna until 3 May 2026.