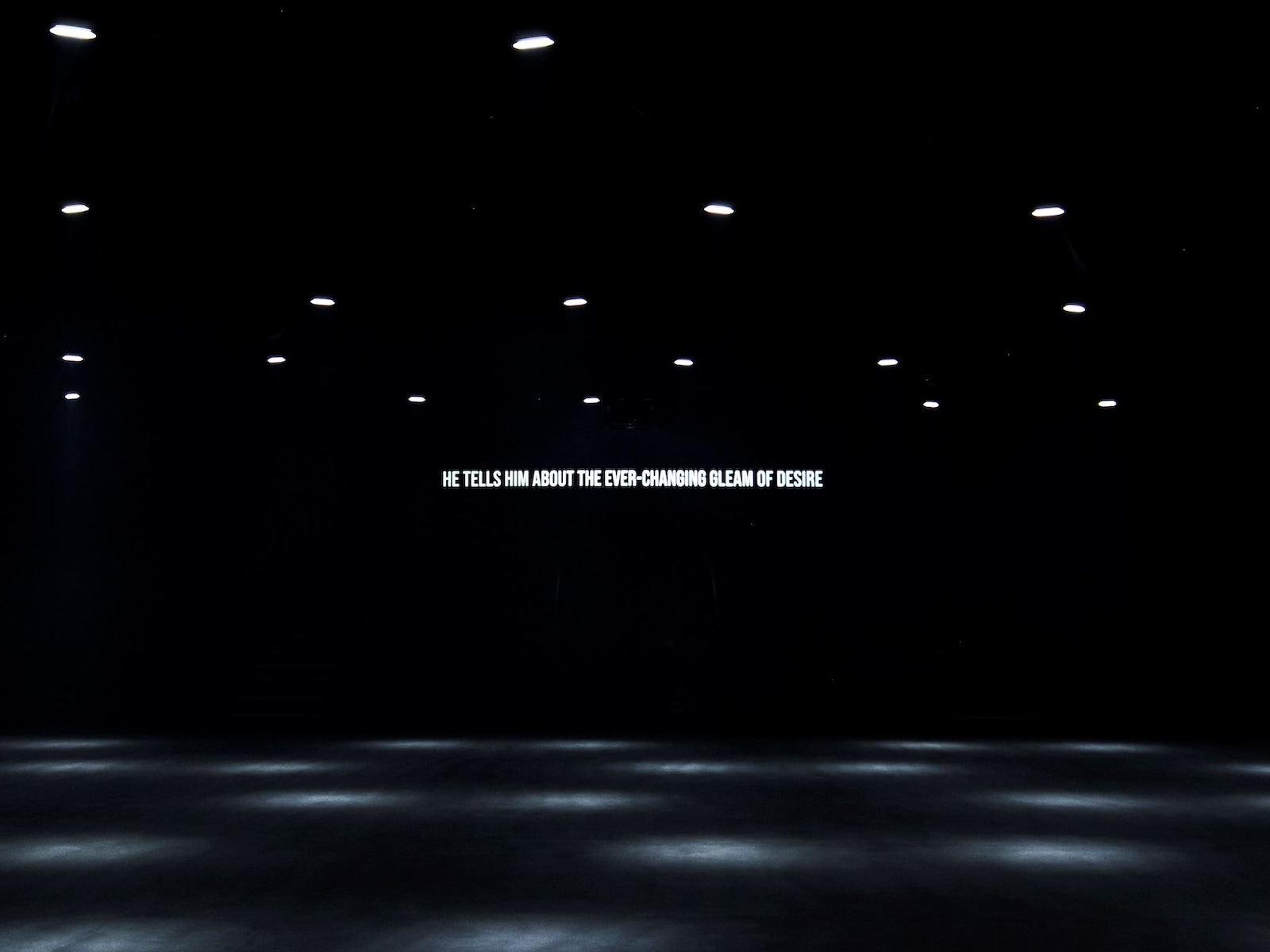

Alessandro Michele was searching for the light, he said, in his latest Valentino collection. That was both literal and metaphorical. For the literal, he partnered with an artistic duo, Nonotak – founded by visual artist Noemi Schipfer and light and sound artist Takami Nakamoto – to animate his Spring/Summer 2026 show space with their immersive kinetic artwork Sora, translating to sky from Japanese. With whirling overhead lights embedded in inky darkness, it was a piece brought to Michele’s attention by his partner Giovanni Attili. Michele, Schipfer and Nakamoto worked on the piece for three months, re-engineering it to the custom-built showspace at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris.

“I was looking for light. I am obsessed with light. I wanted to recreate a very intense space,” said Alessandro Michele, an hour or so before the show. “The only message is going to be the light.” He was backstage, in a dark box of a room – not much light there – discussing his collaboration with Schipfer and Nakamoto on the spectacular installation that would open this latest Valentino show, a landscape of moving light modules shifting like stars in the sky. “I was looking for someone that got the language of the light, like a poet,” he said of that duo. “And they manipulate light in such an incredible way.”

The show itself would be staged in half light, flickering and pulsing like a living entity as the models walked. “The beginning of the show is like a storm of light,” said Michele. “It could be a war, it could be lightning, it could be the beginning of something – or the end. It’s a circular thing.” The whole idea was to create a black box where you’re confronted,” said Nakamoto. “We wanted to create a really immersive but also confusing experience.”

For Michele, this installation – and this collection – is keyed to the experience of this particular moment – fraught, confusing, somewhat brutal. He was, inevitably, thinking about the hallmarks of Valentino – a lightness, an elegance, a kind of glacial beauty that throws back to a very specific breed of mid-century Roman couture. “The world in that time was easier – nothing was ambiguous,” Michele says. “King, queen, rich people, jet set, workers.” And now? “We have the world outside – we have bombs, people that are dying. What can I do with all this beauty? Where can I put it?”

It made Michele, to a degree, question his own role – “As a fashion designer I ask – why do I do this job now?” Michele said. His response? To use fashion as a tool for communication. “In a philosophical way it’s a way to reflect who we are, what we’re doing.” The collection itself was a response – Michele felt it was more precise, cleaner, honing the beauty of Valentino to clean lines, a reaction to the morass of information bombarding us today. “The emptiness. The light. The bodies. And the clothes,” he said.

The light installation was reconfigured – slightly – to ensure we, the audience, could see those clothes clearly. But the intent and impression remained. “It’s an installation that’s really hypnotic – with this rotation movement, this choreography of light,” Nakamoto said. “It’s about stars moving all around the sky, synchronised together. Slowly changing.”

The clothes themselves were lighter – Michele stripped everything back, the glorious confusion characteristic of his work honed down – perhaps a natural reaction given the less-than-glorious chaos that characterises the world at large right here, right now. Michele took inspiration, he said, from a letter written by Pierpaolo Pasolini as a student in 1943. “For me, it’s like a love letter,” Michele said. “In 1943, the war was still alive ... but the words of this letter are so intense. The idea that during a war he’s talking not just about the light, but that he was missing sensuality. It’s such a strong word.” His clothes here seemed to focus on sensuality of fabric, engaging material with skin. “I want to clean up a little,” Michele said, with a smile. “Keep only the most beautiful things.” Like trailing draped evening gowns, or ribboned blouses, or rich embroideries flickering in the half light. Beauty here was seen as an antidote to darkness, the pieces shining out of blackness – itself, a metaphor for the philosophical darkness that surrounds us. Michele called the show Fireflies, after a phrase within that Pasolini letter – fireflies representing the ability to resist darkness, to survive the darkness of the ruling fascism of his era – and, maybe, of ours.

Throwing back to Schipfer and Nakamoto’s notion of the hypnotic, Michele engaged the choreographer Alessandro Sciarroni to devise the models movements, ending in an en masse finale of figures frozen and staring into an artificial sky, whether in wonder or fear. Or, indeed, in hope, searching a horizon for something new. Which is what fashion is all about – but here, was given a deeper meaning.

“I’m delivering a message – that we can altogether find the light,” Michele said. “That is what I would love to say.”