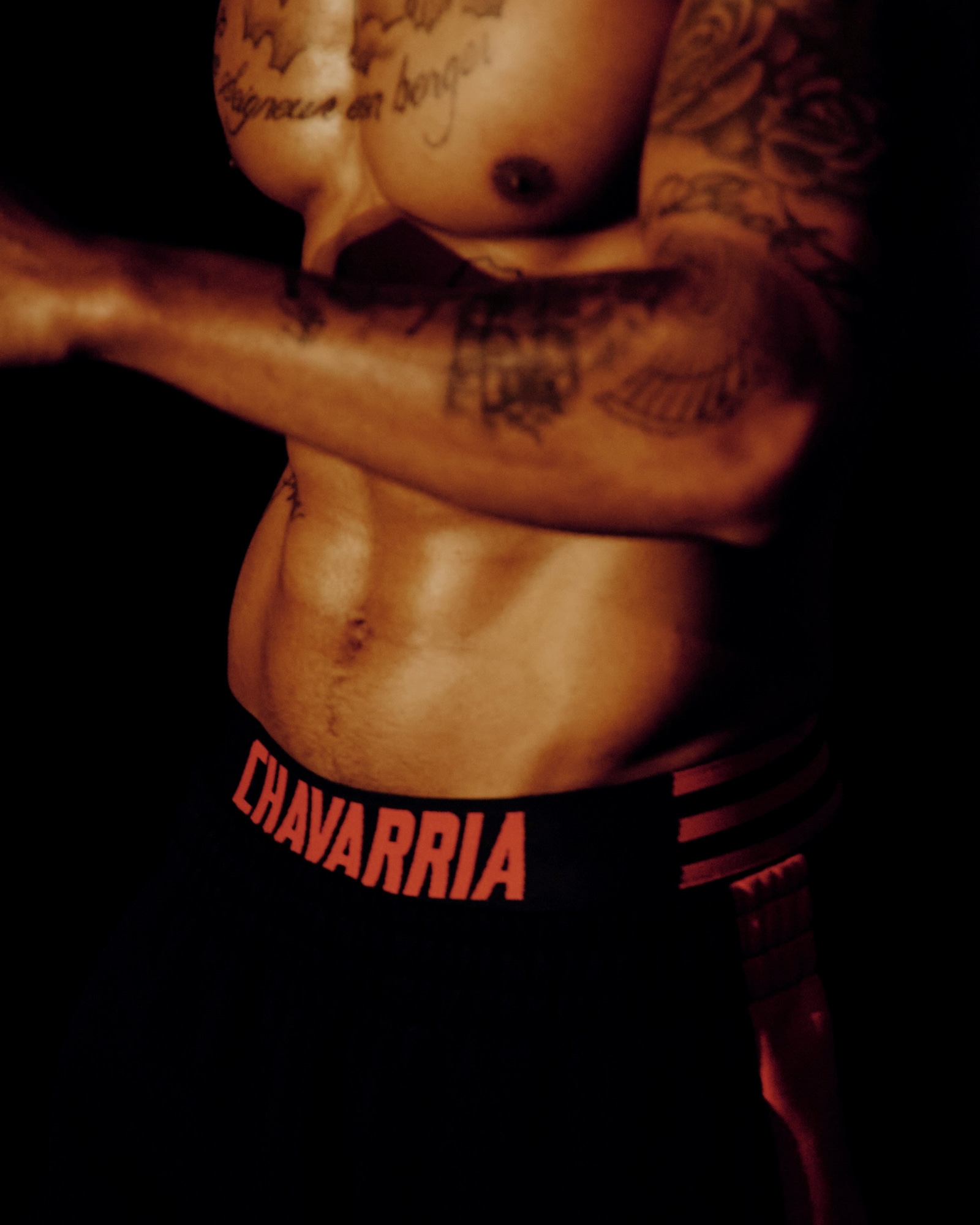

At midday, before his Spring/Summer 2026 show in Paris, Willy Chavarria and the movement director Pat Boguslawski are briefing a phalanx of 35 men – some models, many not – about the opening sequence of the show. In a reflection on the dehumanisation of immigrants in the United States (based on horrifying images emerging from prisons in El Salvador), every man will wear a T-shirt created in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union.

Chavarria spoke to the models: “We’re going to deliver a very strong message about the erasing of people,” he began. “The name of the show is Huron, which is the name of the town I grew up in, in California. And right now, as we speak, my town Huron is being attacked by ICE.” His voice broke. “People are being taken away and put in prison. What we’re representing here are the Brown and Black people, taken from their families.”

Four hours later, those men would be kneeling, dressed in white, in a single row, heads bowed. As an image, it resonated wide – it was also heartfelt, and brave. As is well-known, speaking up against the Trump administration can have repercussions for US citizens and visitors alike. But, in Chavarria’s own words. “It’s always important for me to speak about what’s happening … Everything we do, whether we want it to be or not, is political.”

That said, this collection was not, aesthetically, dark. Rather, it popped with saturated colour – spearmint, thick yolky yellow, a socking cobalt under the sloping, graphic brims of traditional black Cordovan hats. The hues, Chavarria said, came from the humble uniforms of warehouse and factory workers from around the world – Colgate green, Amazon blue, the scarlet of Coca-Cola co.

Here, they were elevated to high fashion, executed in deluxe, Italian-milled fabrics , whether a simple cotton or a blistered metallic cloqué which, Chavarria said, was very “Carol Burnett … a bit Liz Taylor”. Indeed, there was a slant of mid-century couture to these clothes – albeit via Palm Beach, with big Deeda Blair blow-outs over to a trio of ballooning gowns in Ikea blue, yellow and a hot spanked pink, and a slithery column with a pouched coccyx in a warty puce. But the same feeling could be eked out of a polo shirt, or bomber with cocooning back.

Where did the impetus for all that colour come from? “It started in a very superficial way,” Chavarria reasoned. “I want to do joy this season. I wanted to turn the tables. That was five months ago, six months ago. And as things progressed … the idea of what this joy means transformed. Now, what this joy is, is endurance. A sign of endurance, a sign of hope, a sign of rebellion.”

And for me, in Chavarria’s generous, joyous tailoring for men and women, there were unmistakable nods to zoot suits, the brightly-coloured, dandyish tailoring that Black and Hispanic youths wore as a form of protest through extravagance in the 1940s. They elicited violent reactions, too: in June 1943, in Chavarria’s home state of California, what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots broke out, with American servicemen attacking young Latino and Mexican Americans. They stripped them of their zoot suits, ostensibly because they considered their profligate use of fabric unpatriotic against the backdrop of wartime rationing. In fact, of course, it was racially motivated violence, tinged with fear and loathing. History, it seems is repeating itself.

Why did those suits excite rage? Because they refused to be silenced. They were about fighting erasure, about emphasising presence, about pride. They seem as prescient of now as they were of then.