As the parade of Willy Chavarria’s models took their final turn around the American Cathedral to close his Paris debut, a recording of Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde’s sermon to Donald Trump, urging the US President to “have mercy” on immigrants and LGBTQ+ people, bellowed over the packed pews. If it was a punchy decision from Chavarria’s production team to use it as a soundtrack – the speech was addressed just days before – it was vital for a designer who has long given voice and dress to those othered: “What’s really important is who we are as people, how we love one another, how we take care of one another,” says the designer, speaking in the days leading up to the show. “Essentially, that’s all that really matters.”

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Mexican-American father, Chavarria has been steadfast in his commitment to driving fashion as social activism since the launch of his New York-based eponymous label in 2015. The designer’s vocabulary has, for the most part, been rifted from his Chicano upbringing in Los Angeles and then powerfully exalted to uplift communities typically excluded from the upper echelons of fashion (as well as society at large). Religion has long been a fertile ground for the designer – interpreted as a sanctuary of love and beauty. At the end of his infamous Autumn/Winter 2024 show, the models sat around a candle-lined table in reference to The Last Supper, with Chavarria naturally taking centre place. It’s a lovely twist of fate that he celebrated the tenth anniversary of his brand at his debut in Paris, at the first American church founded outside of the US.

The show was entitled Tarantula after a This Mortal Coil song of the same name that left its mark on a teenage Chavarria. “It’s about this gentle creature doing its own thing, yet it’s vilified – a tarantula doesn’t actually do anything until you provoke it,” he says, speaking from a taxi in New York en route to Paris. “I thought it was quite appropriate with the way of the world right now. So many innocent people are doing the best they can to live their lives yet being treated as monsters.” This apt analogy was the starting point for Chavarria to weave the web of his distinctly American core identity – to which he has given singular form, craftsmanship, and stage – to enrapture a global, largely European, audience.

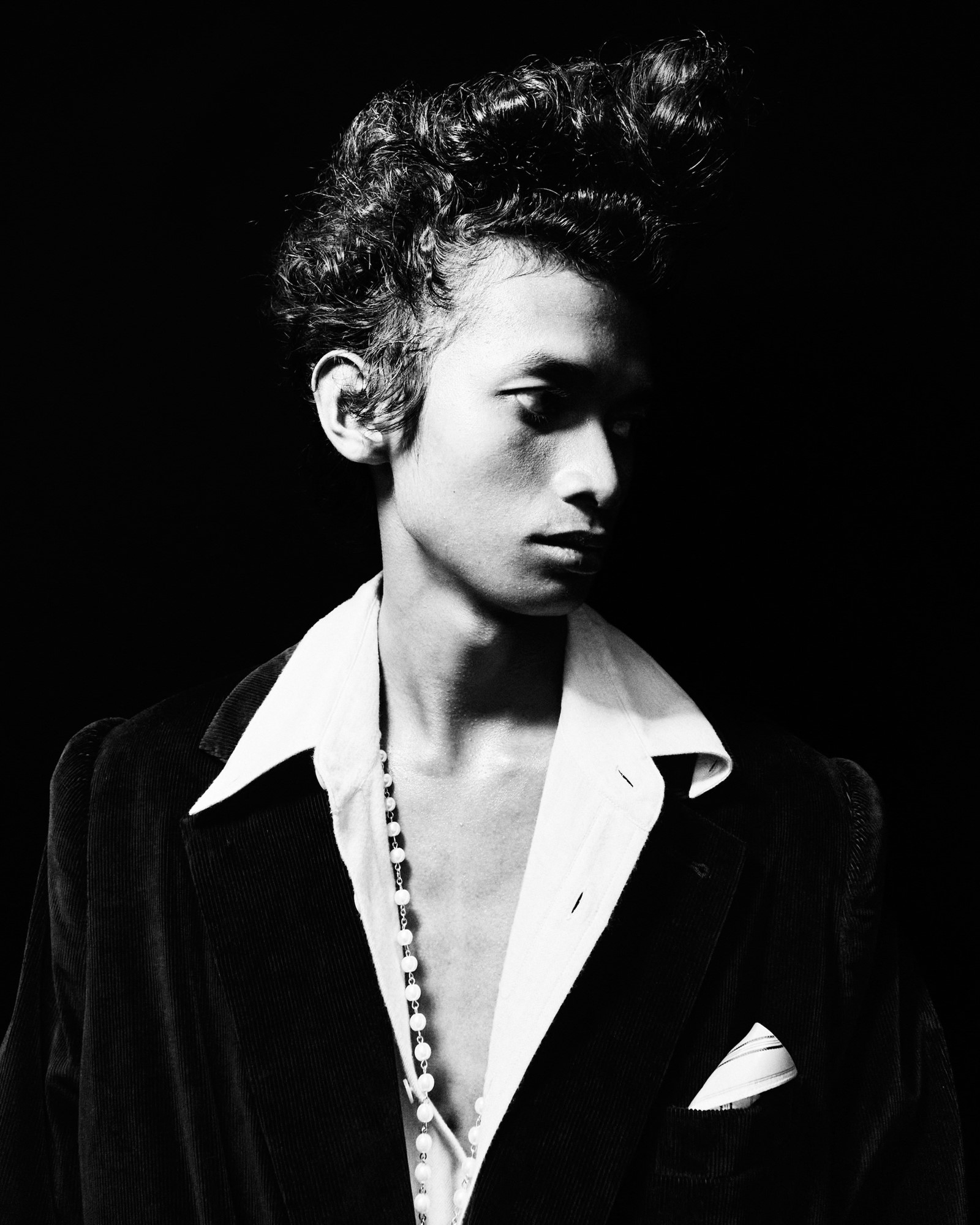

Imagined as a “best-of collection”, the clothes were, still, very much rooted in Chicano culture. Blood-red velvets and sable black wools were tailored into his iconic broad-shouldered, slouched Sunday suits, and then framed with sharp lapelled shirting, neat neck scarves, and flaring cowboy hats. The collection also featured a handful of womenswear looks – slim-cut two-piece tailoring, razor-edged pencil skirts, bustier dresses – although Chavarria presses that he is not launching a women’s collection. “I just want things that are more considerate of the women’s figure,” he says. The entirety was rounded out by pieces from Chavarria’s second collaboration with Adidas.

And then, through textile and palette, Chavarria cleverly cracked open his signature characters and silhouettes to a global humanity. “I was looking at every Caravaggio painting ever done, thinking about rich velvet, washed silks,” he reflected. “I was thinking of chiaroscuro, the contrast between light and dark, good and evil.” The mishmash of formal hues of black and red with electric greens, of velvet and silks with sportswear, purposefully defied sticky binaries of dress codes and labels to “define a necessary in-between.” Simple gestures such as the models’ lowering of hats while within the church setting and the clutching of rosary beads further reaffirmed the designer’s devout commitment to love, between us all.

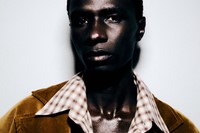

“If you are a woman, a queer person, a trans person, a person of colour or a poor person – those are the people I really love to cast. Those of us who know what it is to be thought of as less than” – Willy Chavarria

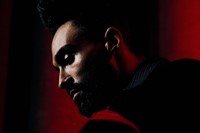

Chavarria has always enlisted personas from his community to walk in his shows, pioneering ‘street-casting’ before it even had a name. To carry this particularly timely and crucial agenda, the designer included both regulars from his New York shows, models street-casted in Paris, as well as big-hitting names like AnOther cover star Indya Moore, Honey Dijon, Paloma Elsesser, and Colombian superstar J Balvin (who also performed live at intermission). “If you are a woman, a queer person, a trans person, a person of colour or a poor person – those are the people I really love to cast,” he explains. “Those of us who know what it is to be thought of as less than.” The clothes don’t wear the models in Chavarria’s world; his models and their lives make his designs. It’s relieving to see inclusivity not ham-fisted, but honest and necessary for the designer and his clothes.

Chavarria is a self-confessed eBay addict; when we spoke, everything he was wearing was sourced from the online auction platform. In a fun self-referential move, he started buying his own archival pieces from eBay and then included them in his runway show. “This philosophy of overconsumption is just grotesque. So, let’s celebrate some of the older stuff!” he muses. “And by revisiting older pieces with each collection it means that the styles and the energy have a continuity from season to season.” (Fittingly, a green velvet suit from the collection was listed for sale on eBay immediately following the show, with all proceeds going to California Community Foundation’s Wildlife Recovery Fund).

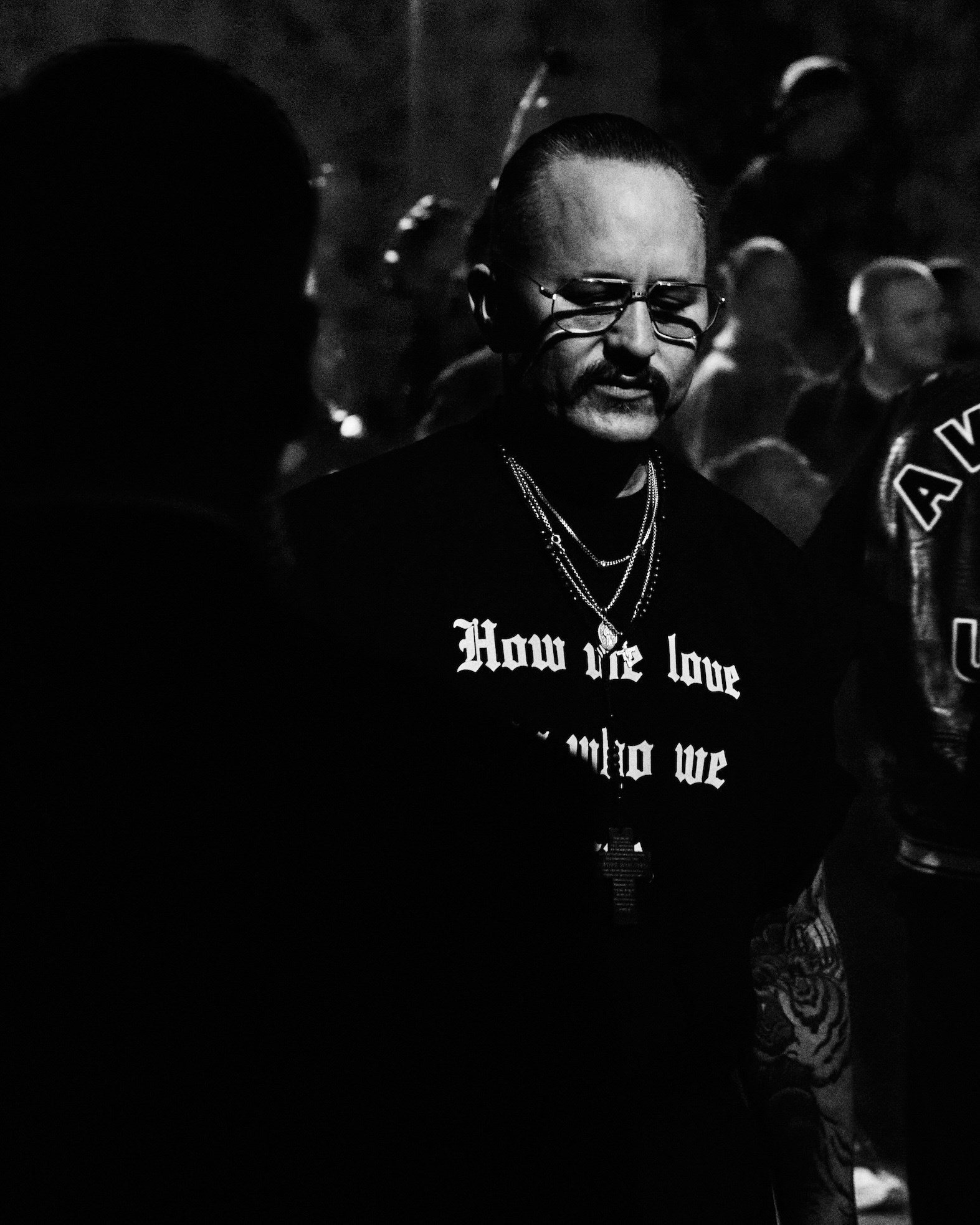

As Chavarria proudly led his community down the centre aisle of the church to close the show, he was wearing a T-shirt from his collaboration with Tinder and The Human Rights Campaign: “How we love is who we are” was emblazoned across his chest (and heart). And it so perfectly summed up what is so remarkable about Chavarria – his deft hand for design and palpable sensitivity for identity to define a singular sartorial agenda at the greater service of humanity. “It is so incredibly important to share the beauty of identity while so many of our identities are under attack,” he pressed. “We really need to use fashion to make sure we don’t forget what is really important.” Chavarria welcomed us all to church, and may his ferocious message reverberate far beyond the realm of fashion.