Since time immemorial, the Bloomsbury Group has held court as one of Britain’s most cited movements in art, design and literature. But aside from hogging undergraduate reading lists, the bohemian circle that lived in squares and loved in triangles has undergone a major runway resurgence.

Indeed, fashion seems to cite the queer aristocrats more than any other discipline. Kim Jones, for example, made his ode to Virginia Woolf’s Orlando novel at Fendi couture Spring/Summer 2021, later recreating the Bloomsbury Set’s countryside escape, Charleston house, for Dior Men’s S/S23 show set. SS Daley, another Bloomsbury buff, nodded to EM Forster’s Maurice for S/S22 and one of Woolf’s lovers, Vita Sackville-West, for S/S23. Even as early as Burberry’s A/W14 collection, the languid daubing of Bloomsbury artists Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell (Woolf’s sister) were colouring trench coats and frocks alike.

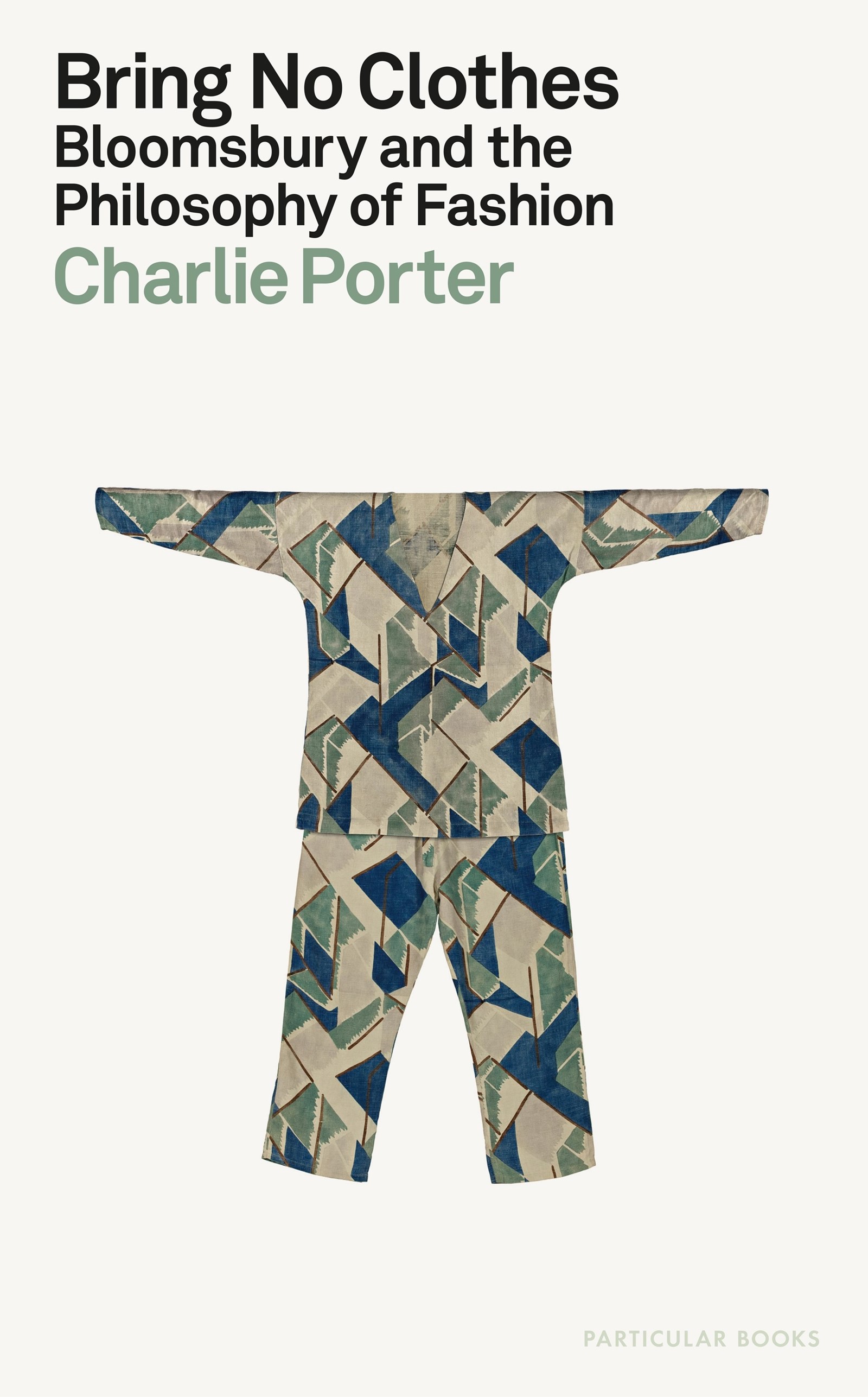

Of course, no one knows this better than fashion journo-turned-bestselling author Charlie Porter, who has spent the past few years scrupulously researching Bloomsbury for his upcoming exhibition and book of the same name, Bring No Clothes. Homing in on six key members – Woolf, Bell, Grant, Forster, economist John Maynard Keynes and arts patron Lady Ottoline Morrell – and their lived experiences of clothing as both a tool of repression and liberation, Porter unpacks questions of class, Empire and queerness, revising a well-told story with the good, bad and ugly.

In the lead-up to the launch of the book, Charlie Porter joins me in his local park to discuss more about the book. We order a coffee, find a dry bench and dive straight in.

Joe Bobowicz: Did the exhibition or the book come first?

Charlie Porter: I was asked to do an exhibition on Bloomsbury and fashion in the summer of 2021 and loved the idea because it wasn’t just the clothes of Bloomsbury, but also 21st-century designers’ responses to Bloomsbury. Pretty quickly, I thought that it could be a book, too.

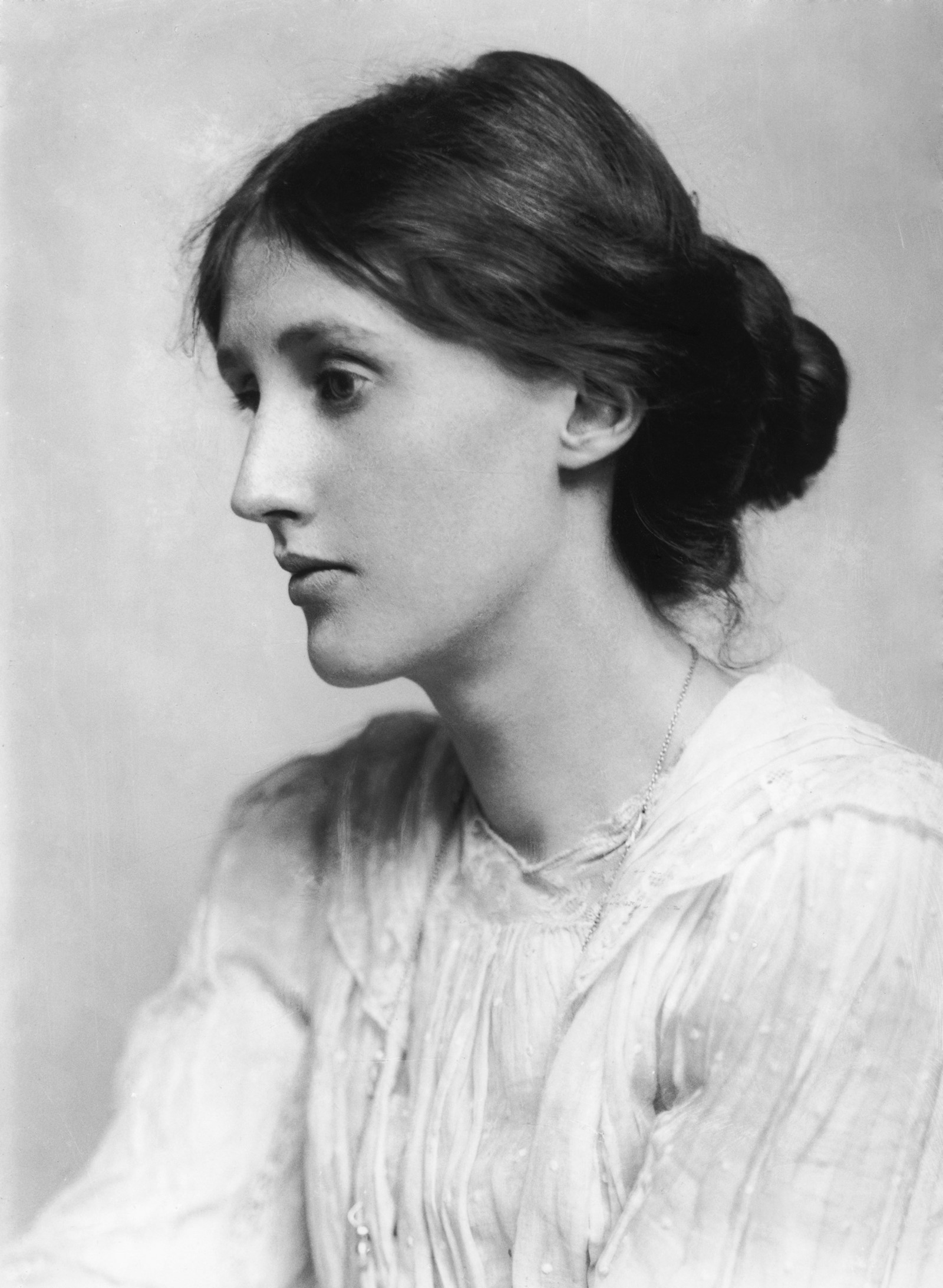

JB: In the book, it becomes clear that Virginia Woolf’s experiences of high society and her half-brother George Duckworth’s abuse had made clothing a source of pain for her.

CP: So, the clothes have been talked about before, but they’ve never been looked at in this way. In Woolf’s lifetime and 30 to 40 years afterwards, most stuff written about her didn’t take the abuse seriously. Her sister Vanessa Bell talks about the same psychological abuse. They lived in a rigidly constructed Victorian house and lifestyle, their mother had died, and their dad really didn’t care about them. So, Duckworth used them as walkers to accompany him into society events, forcing them to wear torture-like corsets and scrub their bodies every day. They were expected to sit and stay silent with no agency. The clothing is crucial to understanding what it was they escaped from in forming the Bloomsbury Group.

“Making your own clothes can be part of a holistic way of living, which includes creative acts, different ways of being, attempting to live and love in novel ways that fit with how you feel yourself to be, rather than censoring yourself” – Charlie Porter

JB: You don’t hide from the Bloomsbury Set’s privilege or shameful aspects of their past.

CP: Yeah. They used anti-Semitic and racist language, and in 1910, they were involved in what became known as the Dreadnought hoax, where a group of six put on blackface and wore clothing pretending to be the princes of Abyssinia [now Ethiopia]. You have to hold them to account [in order] to find things out about colonisation and dressing up. The changes in clothing that were happening to them are the basis of how we dress today. When I was facing up to the Dreadnought hoax, I thought, “If they were alive today, would they have done this?” I don’t think they would. Although that doesn’t excuse them, I do think that allows it to be scrutinised.

JB: One of the parallels you draw is between the deconstruction that Vanessa Bell used in her clothing and the deconstruction seen in Comme Des Garçons collections. You describe it as “thinking through clothing”.

CP: Bell was an artist and made her own clothes. Like Woolf, she had some education but not comparative to her male contemporaries, who studied philosophy at Cambridge. I’ve got a photo in the book where she looks like a comedy version of My Fair Lady in this ridiculous hat, all trussed up. And then two years later, there’s a photo of her at an easel painting in a smock, and she looks so alive. You can see that clothing was a lived philosophy. That is, making your own clothes can be part of a holistic way of living, which includes creative acts, different ways of being, attempting to live and love in novel ways that fit with how you feel yourself to be, rather than censoring yourself.

We know from family folklore that Bell didn’t care about the finish of clothing; she would just pin stuff. It unlocked things for me because I’ve always thought with handmaking – if you get a pattern or watch a YouTube video – you end up with a version that’s not as good as the one you buy in a shop. It hasn’t got the snap that you get when you buy fashion. I came to realise that it’s because I’m not a machine. If you just make clothes without caring, you can be expressive. I think that’s what Bell was doing.

JB: During the research, you started to make your own clothes as part of grieving your own family loss.

CP: It’s been pivotal in helping me. When I started the book, I had no idea about the things I was about to experience. I lost my mum in the summer of 2022, and then towards the end of editing the book, I unexpectedly lost my dad. When I set out thinking about the philosophy of fashion and lived philosophies, I had no idea I was about to live through this. I found if I can move beyond being scared of it, I can just grieve. That’s what making did: it allowed me to just be active in my thinking. It’s meditative; you’re doing a repeated action. Like this cuff here. [Porter gestures to his sleeve.]. It took an hour maybe, all by hand. In that time, my brain can go off and think.

JB: John Maynard Keynes and Duncan Grant had a sexual relationship, and clothing played a role in this. How did you notice this?

CP: I wanted to look at women and men in Bloomsbury. Duncan Grant is an obvious one because he looks great, but his clothes are about the clothes coming off. He didn’t care about clothes. They were shambolic, shabby, always falling off him because he loved sex and naked bodies. But there were these Bloomsbury figures who wore suits, and their suits never changed. Suits aren’t talked about because the people who wear them say, “Why would you want to talk about my suit?”, in this opinion of: “I’m wearing a suit; therefore you don’t need to question me,” which is patriarchal power.

At that time, it was illegal to be a gay male, punishable with jail time. Keynes loved sex – he had a relentless sex drive – and he always wore a suit. Eventually, as he became more famous, he got married to a ballerina, and everyone always says, “And he never slept with a man again.” It’s like, “Because he stopped making lists of who he slept with!” Anyway, there are letters between Grant and Keynes in the British Library. Anyone can read them. They’re so oppressive and heavy because of the imbalance in the relationship. Clearly, Keynes is super needy, and Grant doesn’t really care. Keynes is fascinating because he wears a suit all his life, but his posture breaks the line of the suit. He shoves his hand in his pocket and pushes his crotch forward. It’s intransigent of the line of the suit, which is meant to cover everything as this patriarchal mask. So, he uses his sex to gain power in power dynamics.

JB: In the book and exhibition, you compare Bloomsbury to contemporary designers, like Jawara Alleyne. Was it important to do this?

CP: Yeah. I’m not an academic, so there’s no point in just looking at the past without understanding it in the future. I was just with Jawara in his studio, and he was showing me his collection for Fashion East. I was beginning my research into Vanessa Bell, trying to find a source about her use of safety pins – it was really on my mind. Jawara uses safety pins in his work, both to fasten garments and as decoration. If he wanted, he could run up the most exquisite traditional gown, but he chooses not to. It opened up what Vanessa Bell was doing and made me see her as if I was with her. With Woolf, too – they didn’t have the language to understand what it was they were doing – but I think what they were doing was anti-fashion: something that looks so wrong, it’s right. At the moment, [it’s] what Glenn Martens is doing at Diesel. That’s what Mrs Prada does. It’s an understood part of fashion today, but it wasn’t then. Woolf says in her diaries, “I am resigned to my station among the badly dressed.” People take this at face value. I think she’s saying she just doesn’t fit with traditional fashion.

Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion will be available from Dover Street Market and all good bookstores on 7 September 2023. Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion runs at Charleston in Lewes from 13 September 2023 – 7 January 2024.