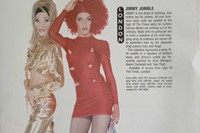

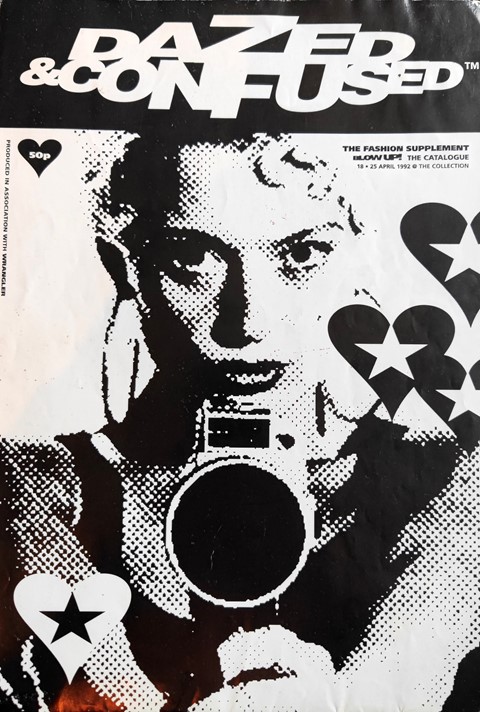

Before becoming a fashion academic at Westminster University, Andrew Groves ran the cult label Jimmy Jumble in early 90s London, embracing kitsch, kink and banality. Here, he talks about why he “allowed it to be chaotic”

Back in the day, Professor Andrew Groves was a darn sight wilder, infamous for his alter-ego-cum-label, Jimmy Jumble. Outfitting himself and clubgoers of the early 1990s, the outspoken creative used his tongue-in-cheek garb as an antidote to what he saw as a scourge of puritanical design, placing kitsch and kink on a pedestal. Now an established academic working at Westminster University, Groves is a cited author and peer-reviewed researcher, but his prankster past remains a treasure trove for students and fashion collectors alike. Today, he answers our video call calm and collected, ready to discuss the fake-nipple dresses and ‘Fashion Police’ jackets that sparked his career.

“So precocious for a 22-year-old,” he says, having just read an interview he gave in an early issue of Dazed. In it, he slates popular designers of the time, proffering instead his irreverent blend of Hysteric Glamour meets Fiorucci and Jean Paul Gaultier. Credit to Groves, though: his work was strong enough to warrant co-signs from Kylie Minogue, Naomi Campbell, Kirsten Owen and the fiercest drag queens holding court in 90s London. In fact, this all came before he worked as head assistant to his former boyfriend Alexander McQueen. Only then would he complete his MA in fashion design under the late Louise Wilson’s watchful eyes, moonlighting as a designer for fetish brand Regulation. After graduating, he opened his eponymous label. Clearly, he was on to something.

Both a brand and persona, Jimmy Jumble began the year after Acid House’s Summer of Love. So the story goes, it was Groves’ birthday and he hadn’t received any presents. Preparing for the night ahead with friends at YMC co-founder Fraser Moss’ flat, he rumbled through the housing block’s mail, happening upon a black and gold lurex jumper to wear that evening. Moss crowned him Jimmy Jumble, and it stuck ever since.

When Groves started designing, his clothes found a natural home in Fiona Cartledge’s Sign of the Times, a Kensington-based shop-club hybrid whose staff spanned DJs, musicians and artist Jeremy Deller. A smorgasbord of found objects, curiosities and designers rising the ranks, from Stüssy to Warhol muse Billy Boy, the store placed Jimmy Jumble in close proximity to other creatives, spurring ideas and healthy competition. Unlike designers working to a traditional fashion calendar, Jimmy Jumble and his contemporaries would be designing for the next club night, as opposed to a fashion show. “It just felt like a social club, really,” says Groves. “You would go in and spend three hours chatting with all these other people, so new projects would emerge from that.”

With London Fashion Week still in its infancy, and only a few designer success stories to come from the Big Smoke, this was a time of mass unemployment, and the likes of Jimmy Jumble were designing solely for fun and a little pocket money. “I was still making stuff to sell in Sign of the Times while also helping Lee [McQueen] make stuff for The Birds collection,” remembers Groves. “You weren’t working every day. I reckon The Birds was three or four weeks’ work maybe, which means you got five months where you’re just down on Compton Street, drinking coffee and then drinking beer.”

Working on a shoestring budget, Groves would buy bizarro fabrics on the cheap, combining them with makeshift haberdashery. His debut piece – a scarlet astroturf jacket dotted with daisies – quickly garnered attention in the clubs, summoning business enquiries and eventually gracing the cover of Jackie, a popular teen girl’s magazine. It sounds odd, but this was a time when independent boutiques played a big part in the mainstream. Following the 80s’ rise of the stylist, the 90s saw an explosion in pop music appearances and TV channels, which meant big business for record-company stylists keen to differentiate their clients. As such, Jimmy Jumble soon found its way to Top of the Pops regulars Belinda Carlisle and Betty Boo.

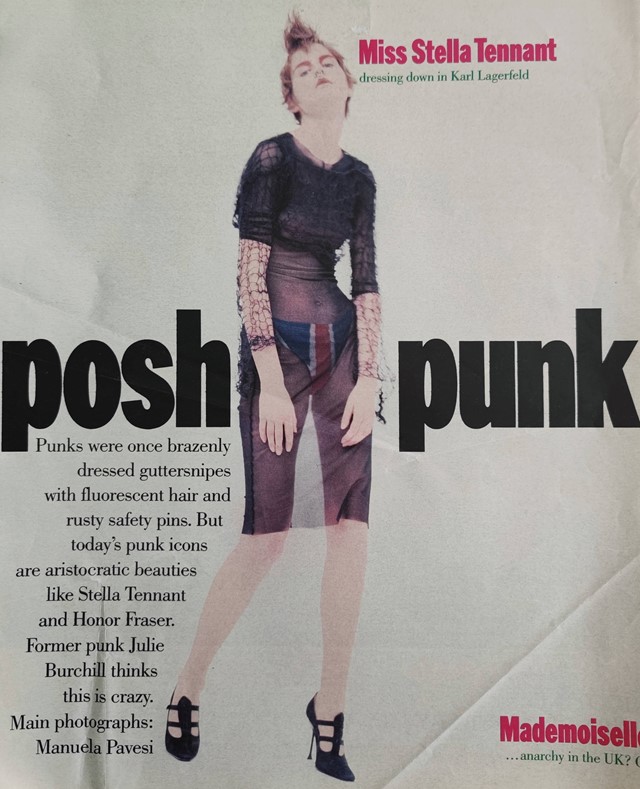

After this pop explosion came Groves’ recognition in high fashion circles, a moment confirmed by Stella Tennant’s patriotic flash of Jimmy Jumble’s Union Jack undies in a 1993 Sunday Times issue. Of course, he never eschewed his outsider-inside status, using clothes to critique their native industry and the culture they exist in. Citing Jeff Koons and Moschino as inspiration, he embraced irony and played with taste, using banality and pornographic jibes to confront his viewers. In practice, this meant PVC coats appliquéd with tart cards, cut as if it were Balenciaga couture, or T-shirts printed across the breast with fried eggs, melons, jugs or simply the words ‘tits’. “You’re almost getting that punch line in before someone else,” he explains.

His own biggest ambassador, Groves would attend Sign of the Times’ parties in Jimmy Jumble’s weird and wonderful concoctions. Whether it was deconstructed, safety-pinned gimp hoods and surrealist cloud-printed jackets or canary-yellow catsuits, PVC skirts and moon boots, one thing is sure – Groves made a statement. Taking place across the city, from Brixton’s Astoria to the West End’s Stringfellows, these nights magnetised a hotchpotch of baronesses, East End builders, and pilled-up ravers, forming the perfect milieu to showcase his work.

The closest he came to an official catwalk show was the time a 60-something regular at Cartledge’s knees-ups, known as Rave Granny, modelled Groves’ garments while off her face, refusing to step off the runway. “It was more about having that happening in this environment and seeing what happens. I allowed it to be chaotic,” he says. “Whereas if I was doing something now, say with the students, you want it to go right.”

Indeed, Groves’ life is worlds apart from the days of Jimmy Jumble, but that same mischievous approach courses through his veins. By taking it too far, Jimmy Jumble widened the goalposts of acceptability, giving another generation of designers more room to wiggle and cause chaos.