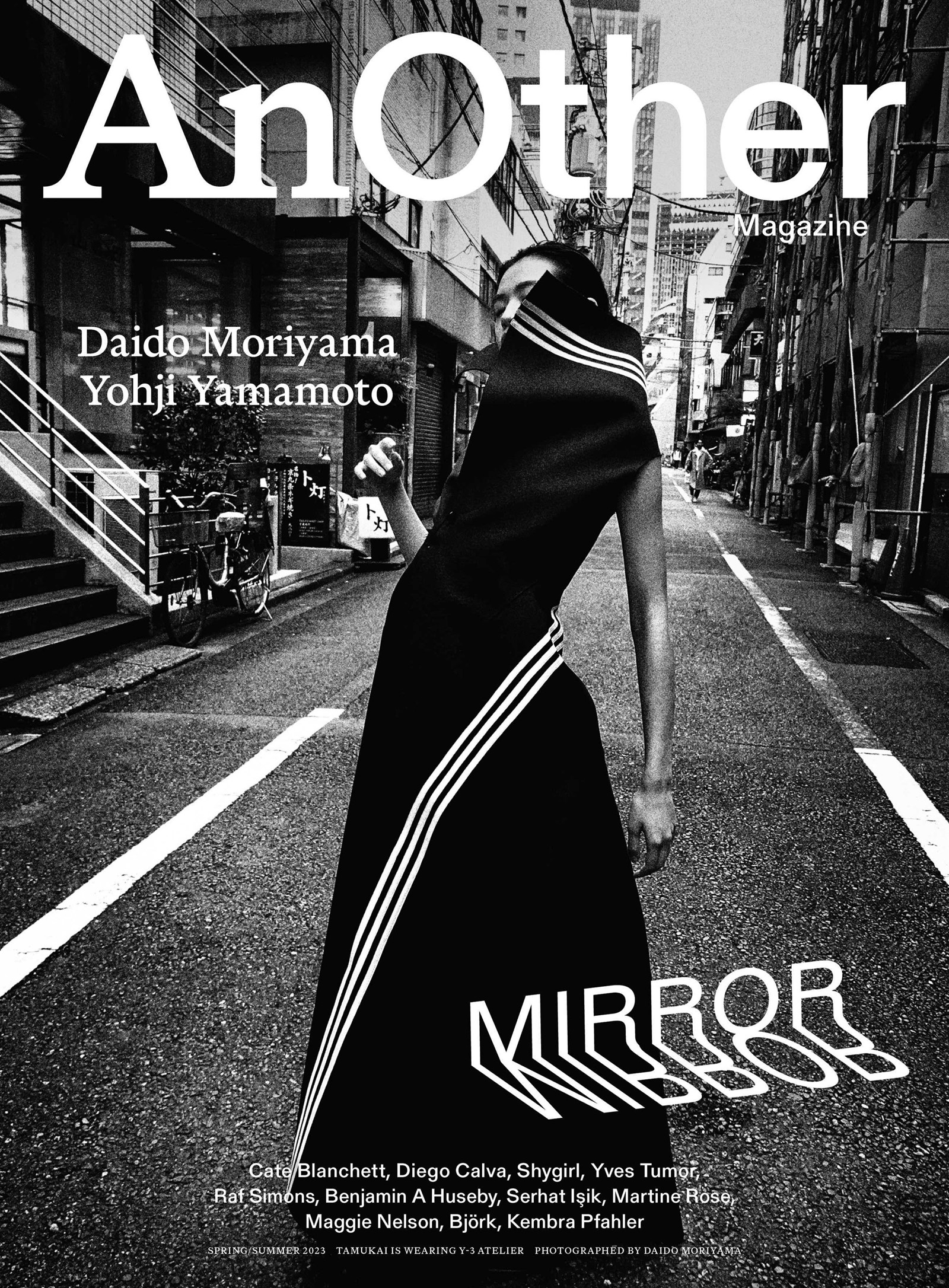

This article was taken from the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

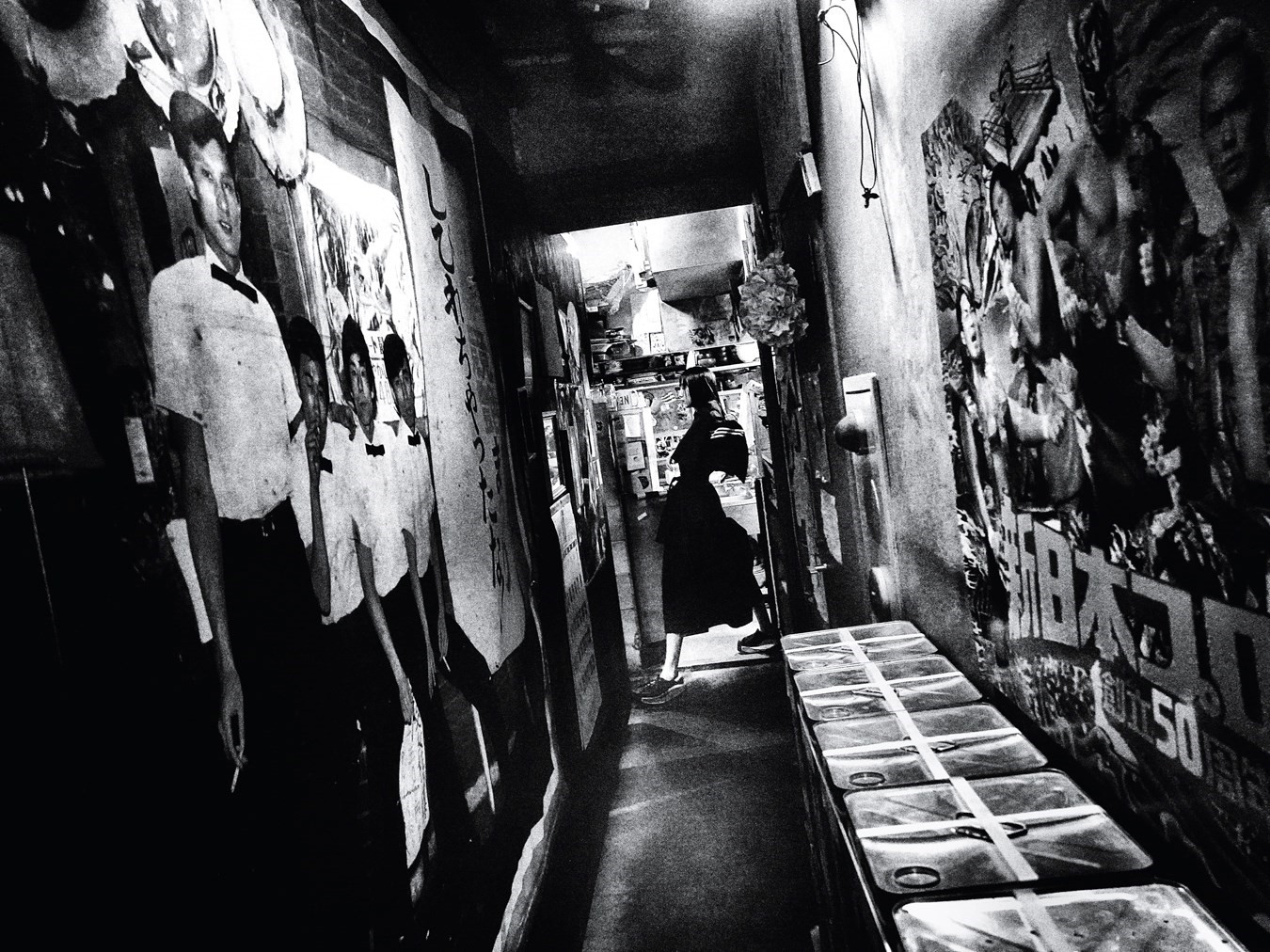

Fashion is, at heart, a reaction. A reaction to the moment in which we live, politically, culturally, economically, and also a reaction to what has come before, to history, to the history of fashion and, sometimes, to the history of a designer’s own work. From that history, Yohji Yamamoto’s collaboration with Adidas, later to become Y-3, was born. The designer’s aesthetic, developed in Japan in the late 1970s, originally had its roots in the country’s workwear, specifically men’s, also in part inspired by the robustly beautiful portraiture of the photographer August Sander. Incidentally, Sander’s imagery – capturing a cross-section of society in early-20th-century Germany – finds contemporary reflection in Daido Moriyama’s visions of Tokyo from the 1960s to today.

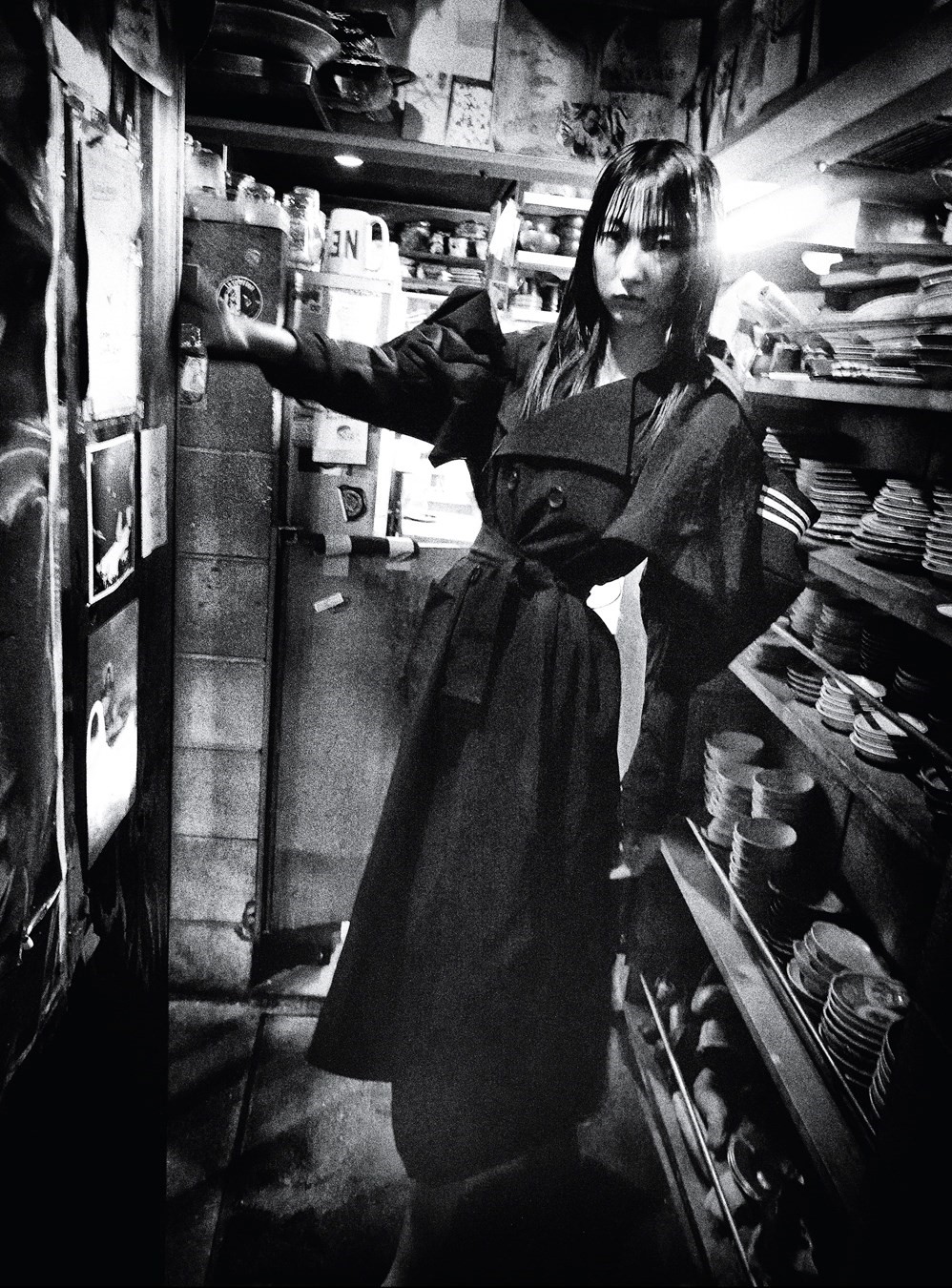

Over time Yamamoto’s aesthetic became less direct, more rarefied, more visibly poetic – romantic, albeit a romance specific to its creator, hence unconventional. Yohji – as Yamamoto, the man, is referred to in person by those who know and love him – once told me that he was “scared” of the red lips and bare skin of the sex workers he saw in his formative years. The enveloping, principally black or navy silhouette with which he made his name and which he took to Paris in 1981 – where, pandemic aside, he has shown ever since – is a clear response. Indeed, it proposes a diametric opposite. It is impossible to underestimate the effect these clothes had on the lives of the women who wore Yohji at that time – and today, still. Fashion commentators labelled them “crows” in the first instance, yet those women saw and identified the fact that here was a designer who treated them as far more than arm candy, a man, in fact, who disliked that mode of thought intensely.

By the late 1990s, Yohji was looking more at traditional Western dress, French haute couture in particular, for inspiration. At the start of his career he openly expressed dislike for bourgeois fashion – conservative tailoring, superfluous ornamentation, high heels – preferring a dark palette that focused the attention on innovative pattern-cutting and oversized shapes, distressed fabrics and asymmetry. His work upheld the beauty of imperfection and embraced and protected the body inside. It wasn’t long, though, before he started playing with the very tropes he had reacted against in the first place, with clothes that had their roots in convention, in an elite world that spoke only to the few, both in terms of vision and price. But Yohji’s rebel intention was to question and subvert.

For Spring/Summer 1997, Yohji reimagined the entire history of 20th-century fashion. It was bold, brave, improbable, with everything from Edwardian ladies, through Chanel tweed suits, to reconfigurations of Dior’s New Look, most memorably in mimosa yellow. Two years later, his seminal Spring/Summer 1999 collection, Brides and Widows, took what he described as the two pivotal moments in a woman’s life – her wedding and the loss of a life partner – as exploration of societal norms. Why, he wondered at the time, does even the most forward-thinking woman – his woman – revert to, even dream of, tradition? Indebted to established notions of formality and to masculine and feminine dress codes, from crinolines and corsets to the perfect trouser suit, if literally taken apart at the seams – it was as technically accomplished as it was moving. More than a few in the audience wept. One season later and a broader and gently revolutionary take on mid-20th-century French fashion took to his runway, showcasing, among other things, his masterful cut. Other designers came to pay homage – Alexander McQueen was in the audience of that Autumn/Winter 1999 show. A year earlier, Vivienne Westwood appeared on his catwalk, an exceptional outing – she only ever otherwise modelled for her own-name collections. Yet she, like many, felt an affinity with Yohji. Speaking to this magazine in 2018, Westwood said, “If you’re a good designer you appreciate and love the work of another good designer, because they do something you don’t do and that’s what you really like about it. Yohji’s work is a look and a big idea. I love Yohji.”

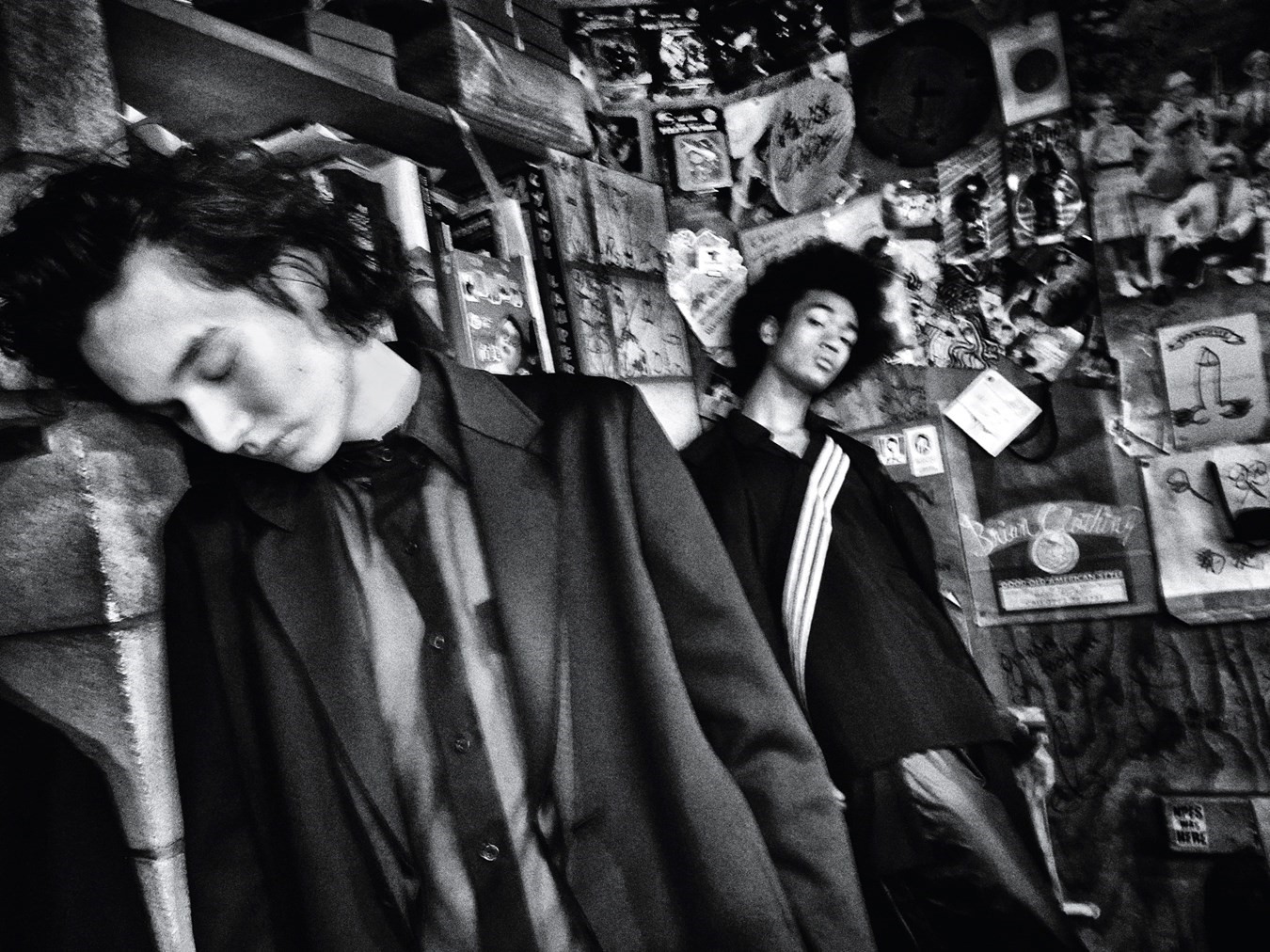

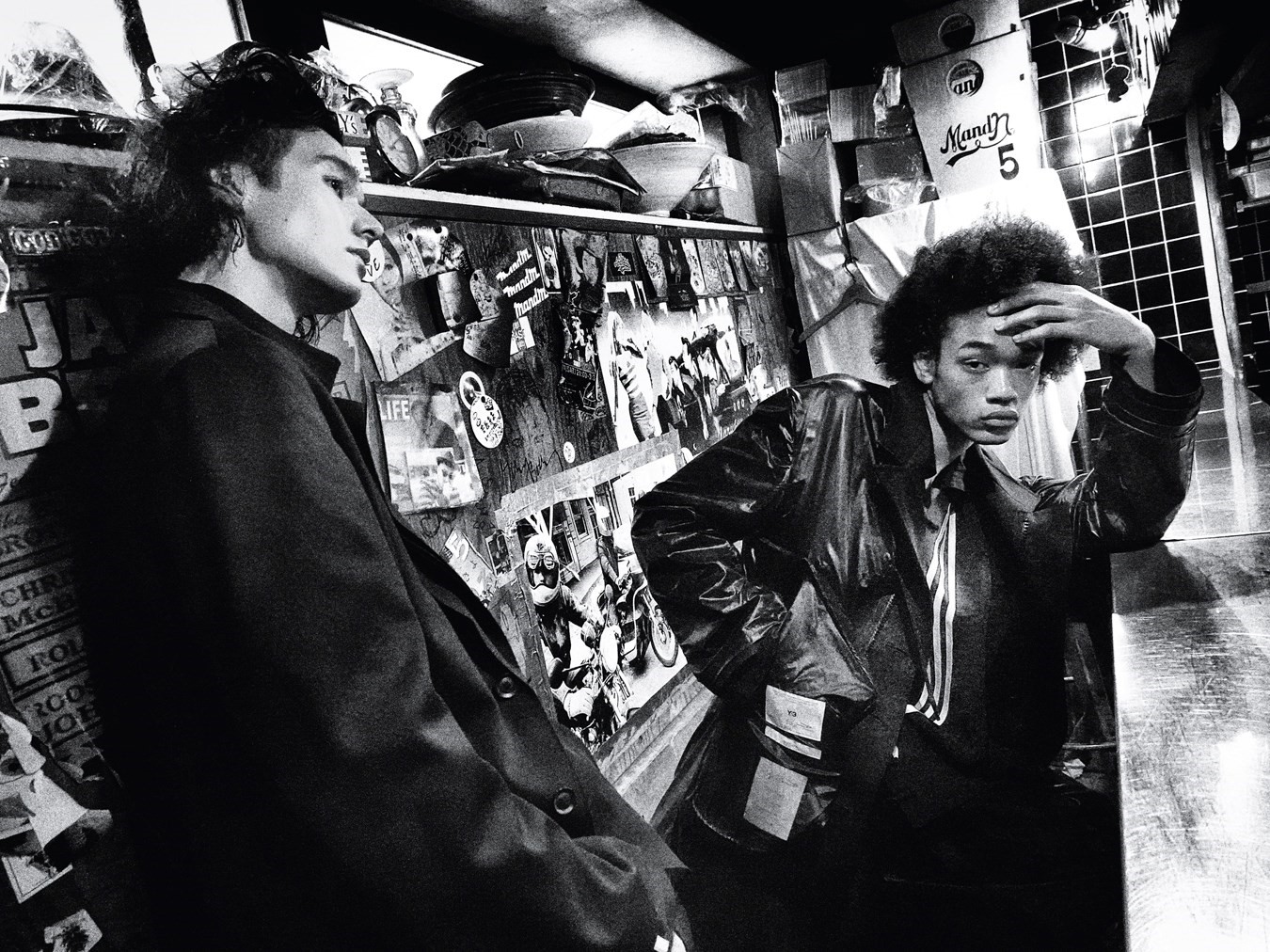

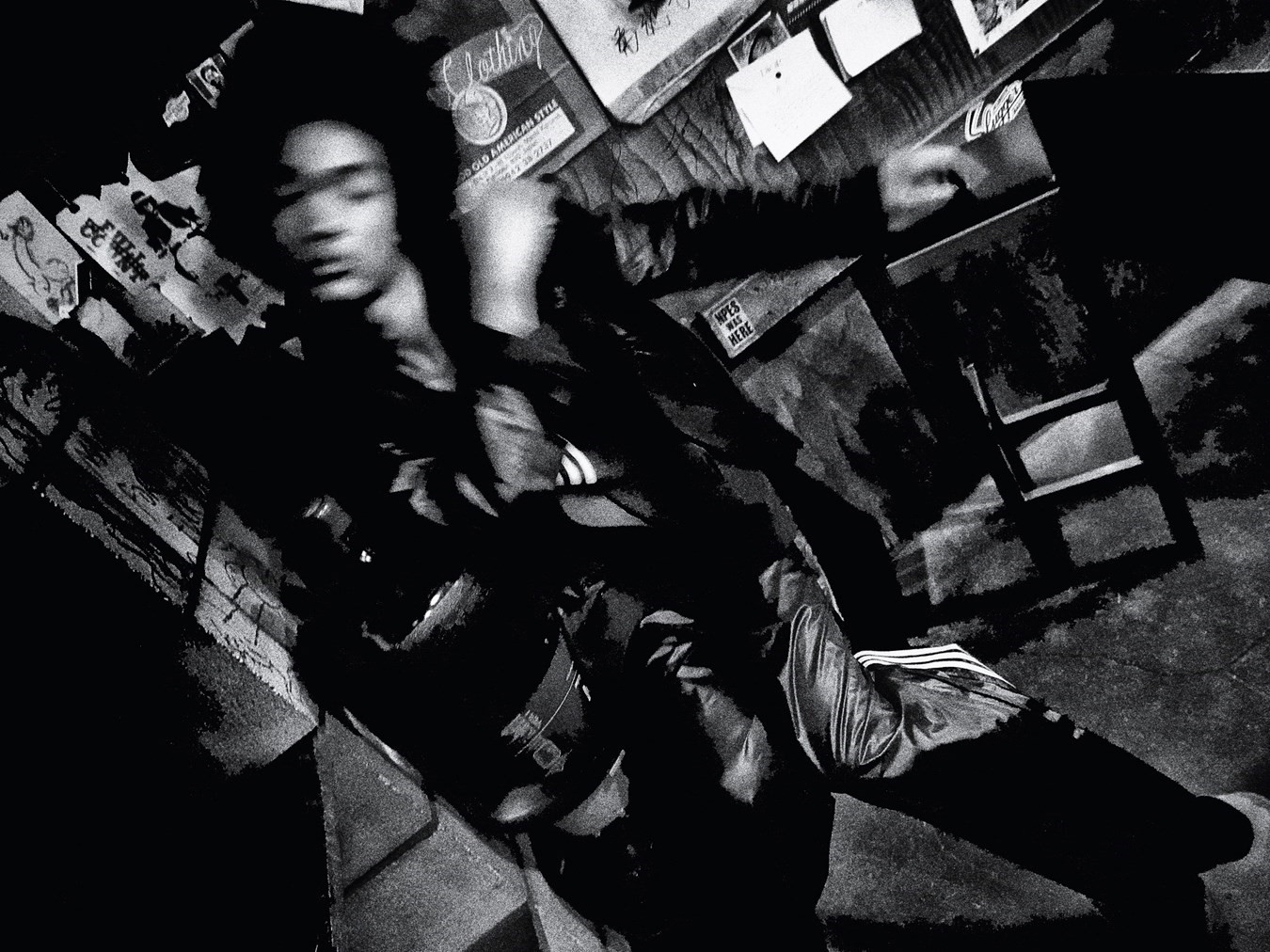

As the millennium dawned there came a fairly radical about-turn. Reacting to his own extraordinary recent output, Yohji felt he had come too far from the reality of both his native Tokyo and adoptive Paris. While many believe that his collaboration with the sportswear giant Adidas began when Y-3 was first shown for the Spring/Summer 2003 season, in fact the Yohji Yamamoto Autumn/Winter 2001 collection marked the start. It was there in trainers made with Adidas, in boxing boots also created with that name, and in the clothes. The three white stripes appeared across everything from bomber jackets and men’s shirting to fluid skirts, all illustrating Yohji’s singular, asymmetric, draped silhouette, their go-faster clarity made all the more apparent in a stark colour spectrum of black (always), navy, white. They are as universal as Yohji’s clothes are singular, and remain the wardrobe of a loyal and highly specific group of people. The tension between those two extremes was dynamic, life-affirming – new.

No one knew at the time that this one collection would lay the foundations for the most long-lasting and widely respected relationship between fashion and sportswear of all. Since then, such partnerships have become almost as universal as those three stripes – a very lucrative part of our world. But Y-3 was the first, the great-grandfather of them all, born of a designer’s creative response to his world and an especially open-minded corporate giant’s embrace of that mindset. More than 20 years later, Y-3 has its own identity, separate from the designer’s yet informed by his values. Yohji’s contribution to fashion is unquestionable. A revered name on the Paris schedule, his collections continue and in their own beautiful way, continue to evolve.

And the conversation with Adidas evolves alongside.

Susannah Frankel: What triggered your collaboration with Adidas in the first place?

Yohji Yamamoto: I was creating outfits for the Paris collections. About 15 years passed and then I felt myself becoming too far from the street. I felt that the things I was designing didn’t work on the street. So I was interested in sneakers, sports fashion. I made a phone call to Nike, directly. I talked to them and their answer was very sharp and straight – “No, no, no. We will never make that. We are doing only sportswear.” A direct answer, a nice answer. Next I looked at Europe, at Adidas. I made a phone call to Adidas and immediately they said yes – “Yes, we can do that together. Why don’t you come to our office?” So I went, bringing eight outfits, and I made a very small fashion show in the Adidas company. I did it because I felt I had walked too far from the street.

SF: It’s true that, at the turn of the 21st century, you created a series of collections exploring haute couture and tailoring techniques and that was right before you launched Y-3. Why is the street important to you?

YY: When fashion designers become too far from the street, they lose their business.

SF: What Yohji Yamamoto does on the runway is rarefied, the Adidas triple stripe is universal – like Coca-Cola, you immediately recognise it. Why is working with a universal symbol interesting for you?

YY: The three stripes are so charming and at the same time so strong. In the black, putting three white stripes, it’s very strong. I was excited by that.

“I like anarchy. You have to be anarchic if you want to be called a creator” – Yohji Yamamoto

SF: The stripes suggest movement – speed, maybe.

YY: Stripes offer movement and at the same time a message. They’re like a racecourse, the three stripes.

SF: Yohji, are you interested in sport? Do you exercise?

YY: Yes, since I was a very small kid – running, swimming … I like using my body.

SF: Your clothes are romantic – poetic – but maybe there’s a romance to sport, too?

YY: When I started my ready-to-wear, it was after I had helped my mother in her little [dressmaking] shop. I helped my mother’s customers. Mostly they had strange proportions. And I was kneeling down at the feet of these ladies putting pins in their skirts. I felt like, “What am I doing? I don’t like this.” I asked my mother, “May I start my ready-to-wear line?” She said, “You try.” I designed an exhibition of my favourite outfits at that moment. I wanted to make women wear men’s outfits. About three years later I still had no customers. That was a very hard moment in my life because I was paid by helping my mother and I struggled a lot. Then I did a raincoat collection, only raincoats. Then customers came. And one customer far from Tokyo told me, “Your time is arriving.” I didn’t believe it, but finally …

SF: Do you think it’s because raincoats are functional?

YY Yes. Doing all sorts of outfits for women, raincoats were my favourite. I could use waterproof fabric, thick fabric, because coats are far from women’s bodies. I didn’t have the bravery to touch clothes against women’s bodies. I was too shy.

SF: When you started out, you were looking, as you say, at menswear, but at Japanese men’s workwear in particular, I think, which is humble, democratic. So that must link quite well with Y-3.

YY: Yes. I came back to the streets. Primarily I was interested in sneakers and running shoes. Then also in comfortable, sporty outfits. Especially in Tokyo, when I saw women wearing sexy outfits, I hated it. I still hate it. Because, as you know, women’s faces are different, there is no same face in the world. And women’s bodies are different. Each body is different, so it was very hard to come closer to women’s bodies with fabric.

SF: Yohji, you just showed your menswear collection in Paris. The whole issue of gender has changed so much since you started and is so talked about now. Do you approach menswear and womenswear differently?

YY: I don’t think it is different. It’s the same spiritual base.

SF: And for Y-3 even more so?

YY: Even more. Exactly. When I look at the movies, or at the Olympic Games in that huge space, especially like a 200-metre sprint, I find runners – I’m talking about women – have such beautiful bodies, especially at the waist and the hip, but not to touch.

SF: Does a blurring of gender interest you?

YY: If I think about gender I am a little bit … Because I was born as the only child of a mother. I have no memory about my father because of the [second world] war. It was very hard to place my hands closer to women’s bodies. It was terrible. So I wanted to make men’s outfits for women. Very frankly, I love women. I respect women. I never treat women like sexy ornaments. For me, designing or creating women’s outfits is a very serious job.

SF: Sportswear has a huge influence on fashion, especially today.

YY: I feel that sportswear influences fashion very strongly. In the street, even in Tokyo, so many people wear sportswear. When I look at that, and the beautiful sportswear-wearing boy and girl, I feel like, “I’m out of it, I’m too late.”

SF: You’ve already touched on it and we have spoken in the past about the war and the loss of your father. That was a global tragedy – and we haven’t seen each other since the start of the pandemic, which was another one. How has that affected you? How do you feel about it?

YY: When I arrived as a junior at high school I studied the war against America. I lost my father – he was drafted when I was two years old and I have no memory of him. I never pushed my mother with questions about why I didn’t have a father because it would have made her very sad. But I studied a lot. Why did the Japanese army start fighting with the United States? I hate it.

“I love women. I respect women. I never treat women like sexy ornaments. For me, designing or creating women’s outfits is a very serious job” – Yohji Yamamoto

SF: Did you feel with the pandemic and more war that there was a similarity, inasmuch as it was a tragedy for everyone?

YY: Exactly. I notice that super-right-wing people exist in every country and they want to fight. They want to kill and still we have war. I notice that human beings didn’t learn from history. It’s so sad. I’m angry about that.

SF: You’ve always been angry. You always tell me that.

YY: Yes.

SF: You are an angry man but your clothes come across as gentle and you come across as gentle.

YY: Because I am so angry I come across as superficially gentle. Sweet.

SF: I come to your shows, they always move and they are different, but you have your aesthetic – and it’s definitely your aesthetic. It’s meaningful and comes from inside. Some fashion designers change their points of view every six months – big, small, organic, technical. You have a point of view and you stay with it. I’ve watched that for a long time. Sometimes Yohji is super-fashionable and sometimes not so fashionable. But right now it feels that many people, including other designers, are imitating Yohji.

YY: Being copied is very important. I am happy. I am proud of it.

SF: In the past we have talked about punk and the influence of punk and a British vocabulary that has, at times, run through your work.

YY: We used so many materials, like tweed, and old-fashioned British techniques. I visited Ireland because I wanted to design Irish sweaters. I travelled to England, Ireland and Scotland. I went in the first place to buy the thread to make fishermen’s sweaters, Irish sweaters. It’s cotton, 100 per cent, but the people who make it don’t take the oil out so when fishermen wear it and they’re fishing on their boats, in the rain, the sweaters repel water. When I visited Vivienne’s company and that thread-making company I was surprised, even then, that so many such companies had disappeared. Industry has gone out of England. So when young people graduate from university there, they don’t have jobs. They created the power of stock in England instead. Money stock became business. I don’t like it.

SF: And you knew Vivienne Westwood of course?

YY: Yes. I was inspired by Vivienne’s creative outfits. I visited her shop in London and I was surprised by the clock going backwards. I liked it very much.

SF: You became prominent at a similar time. There was a spirit of anarchy at that time, on the catwalk and in the world.

YY: I like anarchy. You have to be anarchic if you want to be called a creator.

SF: Is Y-3 anarchic?

YY: Sometimes, and sometimes anarchists like business. We need both.

Hair: Nero at MA+Talent. Make-up: Uda Masa. Manicure: Mayu. Models: Jeff, Tamukai at Bark in Style, Mikey at Number Eight Models and Sen at Bravo Models Japan. Casting: Taka Arakawa at Babylon. Movement director: Chikako Takemoto. Photographic assistant: Yurika Hirao. Styling assistants: Isabella Damazio, Kevin Cheung and Dominika Ewa Szmid. Tailor: Jana Christel Dahmen. Production: Farago Projects. Local production: Mr Positive. Special thanks to Sylvia Farago, Emmanuel O’Brien, Antonino Cerminara, Stefano Pierre Beruschi, Sarah Hoerl, Charlie Pender, Zara Walsh and Eliza at Bene Studio

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 23 March 2023. Pre-order here.