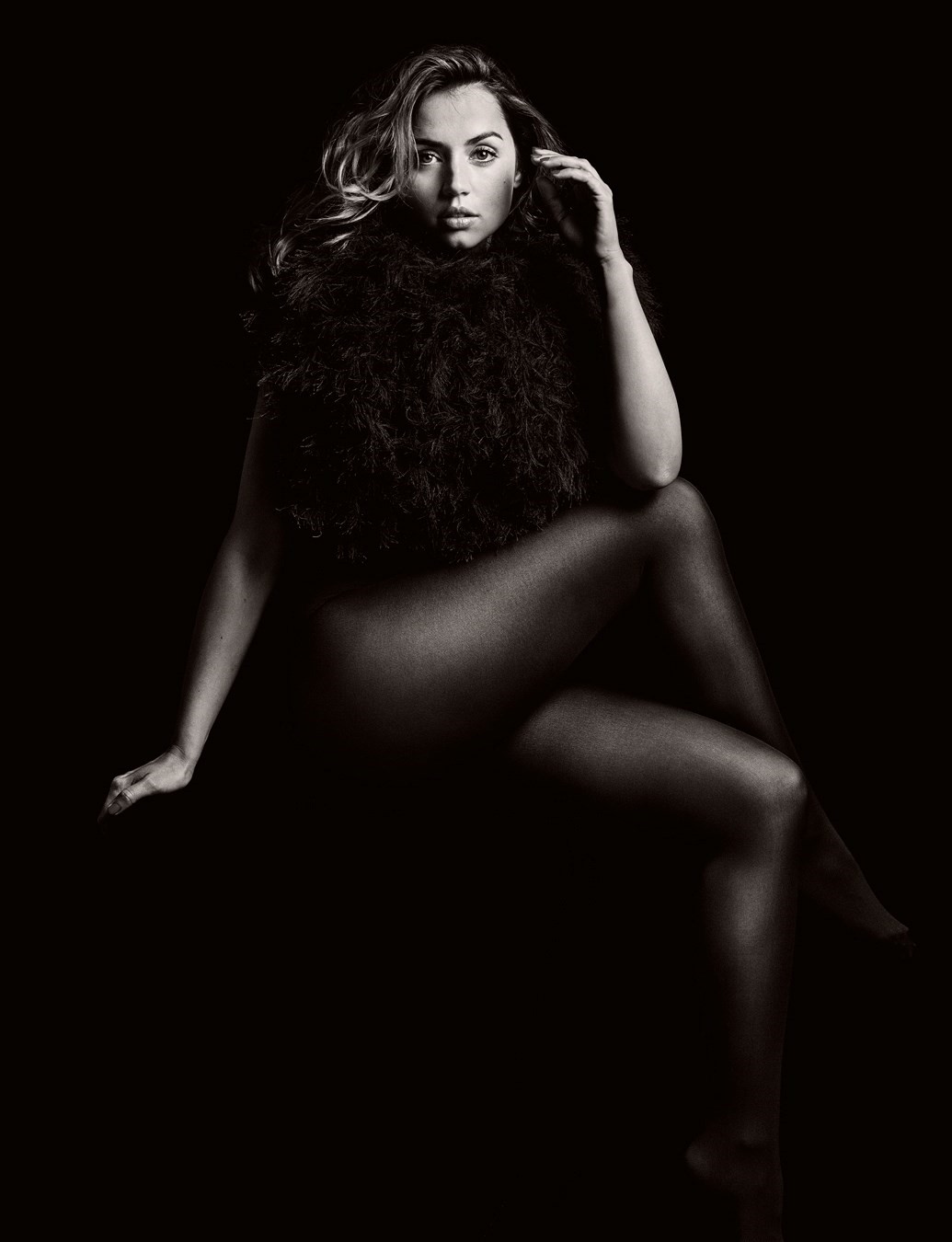

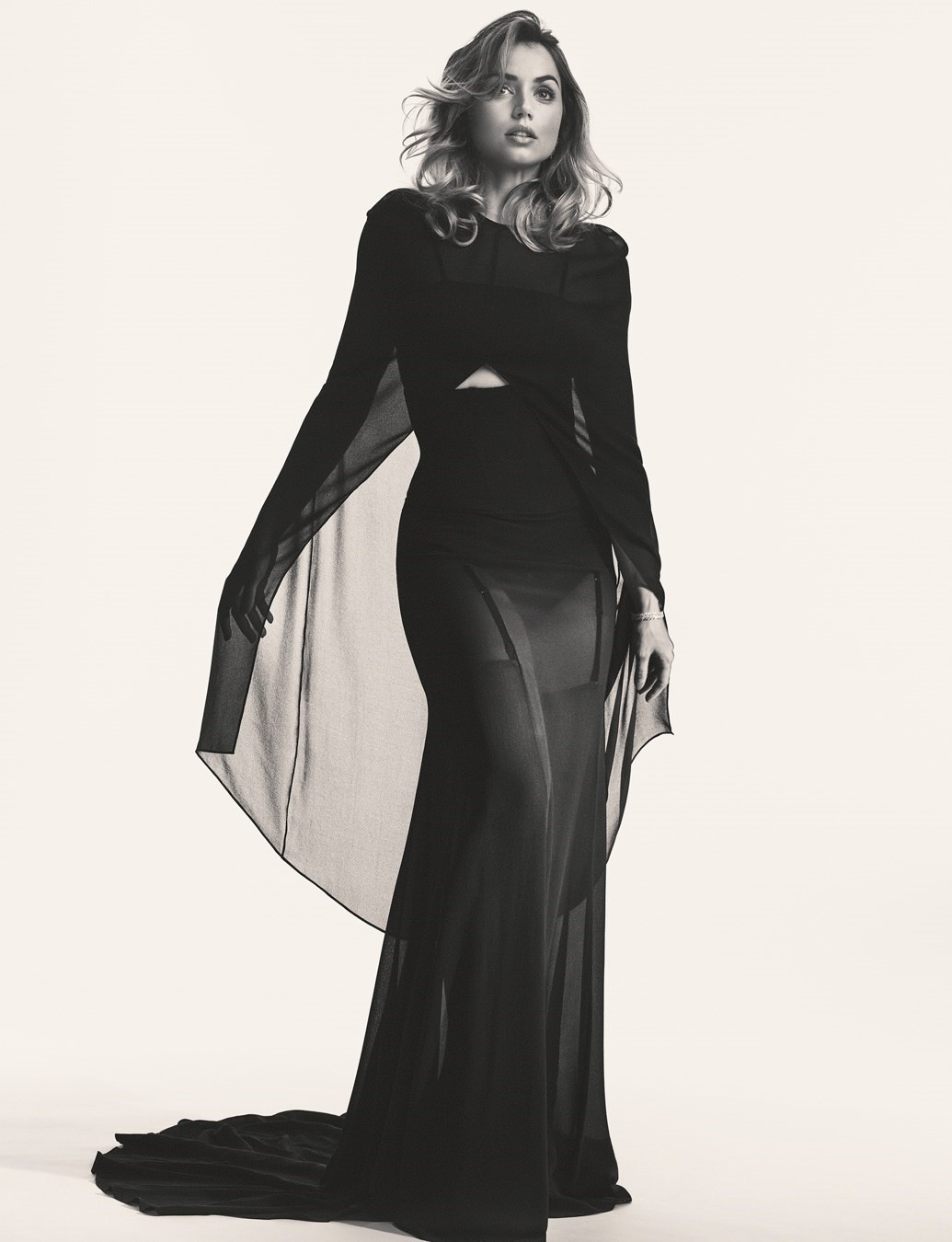

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine:

The deluge of doorstop biographies, tell-all memoirs, rumour and conspiracy theory dedicated to the riddle of Marilyn Monroe’s life has never conclusively solved it.

But we know where it ends: in Brentwood, Los Angeles, on 4 August 1962, in a scantily furnished hideaway with a kidney-shaped pool, a clutter of pill bottles in the bedroom and listening devices planted in the walls. The star was buried in a peppermint-green Emilio Pucci dress four days later, and today her marble crypt is regularly covered in lipstick kisses from fans born long after her premature death. Ana de Armas made a pilgrimage to this quiet corner of Westwood Village Memorial Park on the day she began shooting Blonde, Andrew Dominik’s visceral, heart wrenching fictionalisation of the screen idol’s turbulent life. “We got this big card and everyone in the crew wrote a message to her,” de Armas says as we find a table in the restaurant of a downtown Manhattan hotel on a washed-blue summer morning. “Then we went to the cemetery and put it on her grave. We were asking for permission in a way. Everyone felt a huge responsibility, and we were very aware of the side of the story we were going to tell – the story of Norma Jeane, the person behind this character, Marilyn Monroe. Who was she really?”

For more than 15 years, de Armas has sought roles that swerve the domestic and push her outside her comfort zone. The 34-year-old Cuban-Spanish actor has played intrepid spies and femme fatales, a Dominican sex worker fighting for her life, even a hologram glowing in a neon-drenched, smog-choked dystopia. But it’s hard to imagine a more demanding role than the one Dominik offered her in 2018 – on Valentine’s Day, as it happened. Five years on from the #MeToo watershed, Blonde is an entirely 21st-century take on a 20th-century icon, a confrontational reckoning with the pitch-black stories of Monroe’s treatment by the Hollywood meat grinder. In many ways de Armas’s task was to play not one person but two: the clunkily named Norma Jeane Mortensen, the product of a traumatic and rootless childhood in multiple foster homes across the sprawl of Los Angeles County, and her alter ego Marilyn Monroe, the siren with the ingeniously murmurous moniker who swallowed her up.

Never mind the daunting logistics of stepping into the teetering Ferragamos of Hollywood’s still-undimmed goddess, whose grip on our collective dreamlife – and continued bankability – reached another apex this year when a Warhol portrait of her sold for $195 million. The hours of experimenting with fire engine-red lipsticks and wigs in platinum shades, the months studying Monroe’s swaying walk and megawatt smile might not have amounted to much without one, impossible-to-fake ingredient that happily de Armas has in abundance: the kind of charisma that changes the weather of a scene when she steps into it. Monroe’s own, strange, mercurial talent was legendary, rendering directors infuriated by her pathological lateness and inability to memorise lines awestruck by the alchemy she could work on camera. (Her acting coach Lee Strasberg named only Marlon Brando as having equal gifts.) De Armas’s indefatigable work ethic has little in common with the reported chaos of Monroe’s, but that internal light bulb is something they share. There is an electrifying moment in Blonde when a panic-stricken Norma Jeane is painted and powdered by her make-up artist to coax her bombshell persona from hiding. When the icon emerges from the depths of a dressing-room mirror – heavy-lidded eyes, candy floss hair, jingle-bell laugh – it’s like a match being struck. “She would shine from within,” says de Armas, who is looking pretty luminescent herself today, in a vanilla-coloured dress and loafers, her usually dark hair long and blonde, her eyes an impossible-to-pinpoint shade of both honey and green. Over the next two hours, as waiters come and go with grapefruit juice and coffee, it becomes clear that the months she spent inhabiting Monroe’s cryptic, interlocking selves still deeply affect her. “The more famous Marilyn became, the more invisible Norma Jeane became – Norma was this person no one ever actually met,” she begins. “And Marilyn was someone even she herself talked about in the third person. In some ways Marilyn saved her, gave her a life, but at the same time she became her prison.”

That cavernous split between public and private self is the focus of Blonde – “The story of an unloved and unwanted child who became the world’s most wanted woman,” as Dominik has put it. The director is known for layered explorations into male violence and its consequences, plumbing the psychological waters of gangsters, murderers and outlaws. His 2007 feature, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, shattered the myth of the Wild West and its cartoonish stereotypes, showing bloodshed that was blunt, grisly and inglorious. James was something of a celebrity too – the subject of breathless newspaper headlines and dime-store novels, who, like Monroe, was described as stopping time when he walked into a room. If that film questioned America’s preference for legend over history, Dominik’s latest, produced by Brad Pitt’s company Plan B, puts the myth of the screen goddess in its sights, peeling back its glittering surface to reveal the unspeakable truths that might lurk beneath. “It’s about the things we haven’t seen, the moments when the cameras aren’t flashing or rolling, when Marilyn is not ‘on’,” de Armas says. “It’s fiction. We don’t have proof this happened. But it fills the gaps in the things we already know with a version of events that we should at least consider.”

Traditional biopics might chronicle dates and milestones, but they can fall flat in capturing the messy, nebulous texture of internal lives. Based closely on Joyce Carol Oates’s masterful, Pulitzer-nominated novel of the same name, which imagined Monroe’s life as a macabre fairy tale of cursed princesses and gold-spinning Rumpelstiltskins, Blonde is more spectacular hallucination than faithful record. It mixes pieces of undisputed fact with hearsay to conjure a disorientating hall of mirrors. Much like David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, it drills into its protagonist’s subconscious and into the psyche of the City of Angels, digging beneath the chromed convertibles and plush leather booths to reveal a nightmarish underworld of reptilian moguls, carnivorous press and vampiric doctors all too generous with their prescriptions. “A place where they’ll pay you a thousand dollars for a kiss and 50 cents for your soul,” as Monroe herself once said. The story unfolds like a fever dream, from a childhood gripped by her mother’s frightening mental illness (a film-negative cutter on the fringes of Hollywood, Gladys was committed to an asylum when Monroe was eight; she never knew her father) to her insomniac final years, thoughts muddied by a glossary of chemical substances. Telephones shriek, flashbulbs splinter, the mouths of ghost eyed paparazzi stretch to monstrous proportions and a febrile soundtrack courtesy of Nick Cave and Warren Ellis only deepens the gnawing sense of dread. “So, this is a horror movie, right?” de Armas said, only half-joking, the first time she met Dominik to discuss the role.

For the director, Blonde has been a decade-long obsession: he began writing the script in 2008. Since then, potential Marilyns have come and gone – Jessica Chastain and Naomi Watts included – but when financing finally aligned with Dominik’s vision, it was de Armas he wanted, no matter her Cuban accent. “It was pretty surreal I even got asked to audition, but that just shows how progressive Andrew is,” she says of the slice of history she’s making as a Latinx actor playing the most all-American of idols. “I grew up watching everything from Titanic to The Terminator, but I always knew that reality was so far from my reality. Kids in the US, they believe they can be princesses because you can buy a princess dress and a princess crown and become one. I never had that. I didn’t even know what an apple tasted like. Cuban actors were more relatable to me – Daisy Granados, Isabel Santos, Verónica Lynn – those were the actors I looked up to. I thought I’d be doing that, not Marilyn. But of course I went for it, because I love challenges, and I knew that emotionally I could get there. I didn’t know if the hair, the make-up would, but I understood what we were trying to say. Andrew called me after the audition and said, ‘It’s you. It has to be you.’ But then we had to convince everybody else.”

Convincing everybody else translated to months of work with a dialogue coach to capture Monroe’s breathy, marshmallowy voice, itself a creation by the star to overcome a stammer. “It just wasn’t working when I tried to imitate the sound or the pitch,” de Armas says. “Marilyn’s voice, her expressions, were a consequence of the speech classes she took herself, of her insecurities, of her not having any boundaries and letting people in, of playing this part of having to be rescued all the time. So I had to know what she was thinking and feeling every time. Because the way she rounded her lips for the ‘O’s, or how much of her lower teeth she would show, what her eyebrows were doing, all these expressions were a consequence of Marilyn in survival mode. They were tricks that she was pulling in desperate circumstances.”

“The whole [acting] process was overwhelming for me. Most of the time I thought I was doing it wrong. I was thinking, what are these American actors thinking of me?” – Ana de Armas

To climb inside her character’s head, de Armas devoured a cornucopia of written material: Oates’s immense novel, of course, each page read and reread two or three times, but also anything that offered a glimpse of Monroe’s energy off-duty – a favourite was Truman Capote’s gossipy jewel of a story, A Beautiful Child. Meanwhile, Dominik created a 750-page bible of Monroe photographs that mapped every emotion he wanted to conjure, scene by scene. Blonde is built on a trove of that iconography, much of it burned into our collective imaginations, stretching from early cheesecake pin-ups to Life magazine spreads to paparazzi shots – all while hypothesising what it might have felt like to be the mortal woman behind that mythical projection. “Almost the entire movie exists in photographs we were either recreating or referencing,” de Armas says.

“Almost every scene starts or ends exactly like an existing photograph.” The recreations are breathtaking, switching formats or from monochrome to colour depending on the source. Dominik was fetishistic about the minutiae, commissioning exact reproductions of Monroe’s outfits – more than 100 wardrobe changes – tailored to the last stitch. “It gave me goosebumps,” de Armas says, “and changed everything about the way I moved and felt. Andrew never stopped filming, so he dressed the sound person, the prop guy, my dialect coach, all in period costume too, so the camera could follow me anywhere. And anywhere I turned was ready to be filmed because we were shooting in her real houses.” Those homes include the peeling apartment block a young Norma Jeane lived in for a time with her mother; the orphanage on North El Centro Avenue with its fabled view of RKO studio’s lightning-bolt sign, which flashed through the night like a siren song during her two years there; and the final, hacienda-style home at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive, the modest and only house Monroe bought, at a time when studio magnates filled their gabled mansions with shrieking peacocks and priceless art. “It was a full immersion in her world, in LA, in those studios – spooky and beautiful,” de Armas says. “Andrew loves actors to improvise, so a lot of the time he was on his knees beside me and I was just reacting to what was happening around me.”

When it came to replicating some of Monroe’s most indelible performances, though – including the moment a Manhattan subway breeze meets her white cocktail dress in The Seven Year Itch, and a snippet from Some Like It Hot – there was no straying from the script. De Armas is chillingly good in scenes that left her nowhere to hide. “Andrew had two monitors, the real Marilyn in the scene and me. And everything, every angle, had to be exactly the same. So that was me watching these films hundreds and hundreds of times.” In each recreation, the screen fantasy is stripped away to imagine its fallout. We see Joe DiMaggio’s violent rage, fuelled by the leering crowd who gather to watch his wife’s white dress fly into film history (the couple divorced soon after). And, in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’ effervescent musical number Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend, a take is cut short by Monroe’s screams of anguish – she’s hustled into a dressing room and subdued with a needle. It’s well documented the actor suffered from paralysing stage fright during the making of that Howard Hawks film; on the set of Blonde, de Armas faced down her own spectres of self doubt. “I experienced a lot of fear and insecurity,” she says. “I felt in a very vulnerable position. Not just in specific difficult scenes – the whole process was overwhelming for me. Most of the time I thought I was doing it wrong. I was thinking, what are these American actors thinking of me? They know this person better than me, they’ve grown up with her. What are they thinking about my accent? Andrew could sense that discomfort and right away he told me, ‘That’s how she felt. Embrace it.’ She was feeling insecure and unprepared and judged and undervalued all the time. So I had to trust my emotions were adding to the layers.”

This year, a DNA test of a strand of Monroe’s hair indicated her father was Charles Stanley Gifford, her mother’s colleague at Consolidated Film Industries in Los Angeles. But during Monroe’s lifetime he was a blank space that bequeathed her a bottomless well of unfulfilled need. At first, de Armas struggled with Monroe’s inability to set boundaries between herself and others, finding her own instincts racing in the opposite direction. “In some early scenes I played it way too strong,” she says. “I got defensive and angry and Andrew said, ‘You’re not allowed to get angry. Ever. Anger is not something Norma can afford.’ Well, can you imagine what that does to a person? At its heart the movie is about her looking for an absent father. Part of the reason I think she became Marilyn Monroe was to be so visible there’s no way he could not find her. You see how a childhood of feeling unloved and unwanted led her to need love, attention, need someone with her always. So I thought, OK, if I can’t get angry, what are my options? How else can I survive? And I started to explore all these other feelings.”

If it was her childhood that set Monroe up for destruction, Hollywood swiftly saw to the rest. Both Oates’s book and Dominik’s film chart her vertiginous ascent as coming with an obligation to the casting couch. “I met them all,” Monroe wrote in her unfinished memoir, My Story. “Phoniness and failure were all over them. Some were vicious and crooked. But they were as near to the movies as you could get. So you sat with them, listening to their lies and schemes. And you saw Hollywood with their eyes – an overcrowded brothel, a merry-go-round with beds for horses.” In Blonde, men treat her like a sexual party favour: there are harrowing scenes of assault by a sadistic tycoon and a certain doomed president. Those scenes, and a torturous abortion (it’s never been established she had one), are evidently the cause of tussles over the film’s edit, and its eventual NC-17 rating. De Armas is unflinching in her defence of them: “We tried to show the fight she had to put up, not just to be successful, but to survive,” she says. “What she went through was dark. So dark. When you know that, fuck, I love her more. So the whole point is not bringing down the myth, the point is humanising this icon and making her real, a real woman going through all these different kinds of abuses and situations. And as a woman today I can easily understand how you could find yourself in that situation. So, yes, there are scenes that are hard to watch. But I don’t think this movie has anything sensational or exploitative or gratuitous in it. In many of the scenes people are talking about, you don’t actually see anything. You just know what is happening and that it’s coming from a place of zero love. I do think the audience will feel uncomfortable – because she is uncomfortable. When she feels dirty, you feel that the scene is dirty. It’s all in the way it makes you feel.”

When Oates’s novel was published in 2000, it was feted for its rich imagining of Monroe’s inner world and its excoriation of the patriarchal society that snuffed her out. It also drew antipathy from those who saw it as another exploitation of a woman who has become more property than person. (See Kim Kardashian’s controversial Met Gala photo opportunity in the crystal-scattered nude dress Monroe wore to serenade JFK.) Blonde the film might prove as divisive as the book, but post #MeToo, its unvarnished take feels more relevant than the kind of melancholy tristesse so often attached to tellings of Monroe’s story. For her part, Oates has championed the film, describing it as “… startling, brilliant, very disturbing and [perhaps most surprisingly] an utterly ‘feminist’ interpretation … ”

“I was thinking of her so much, some days I would go home and have dinner and as I was washing the dishes I would just start sobbing, crying and crying, because I had this terrible feeling” – Ana de Armas

“And absolutely, I agree with her,” de Armas nods. “Inspiration is a very different thing from taking. If there’s a reason she’s still not resting, it’s that she’s been taken from so much. I knew as soon as I met Andrew that he was going to take care of her. So for the film to go places like the point of view of the abortion, a depressed mother and how a child deals with that, the desire of all these men over Marilyn, the way they look at her like meat – like a room service delivery – and, yes, the way she allows herself to fall in love and be disappointed again, it’s unapologetic and brave and feminist. Andrew shows pain and nudity and vulnerability and he doesn’t sugar-coat it. I’ve been told by people, oh my gosh this scene is so long! And I think, well, yes, and now you can imagine what she was feeling.”

De Armas isn’t a method actor, but grappling with that darkness inevitably spilled into her life off set; the experience still seems raw. “Don’t get me wrong, I had so much fun. I wasn’t by any means in character for nine weeks, not between takes, not in my lunch break. I was Ana,” she says. “But emotionally? The weight of it stayed with me for sure. There was no way to unplug because I’d get home and study for the next day and then Andrew was on the phone until midnight. I would go to sleep and dream I had long conversations with her, or little things – like once we were choosing which colour vase we’d put flowers in. I don’t want it to seem like I’m saying, ‘Marilyn and I were connected’ – not at all. But I was thinking of her so much, some days I would go home and have dinner and as I was washing the dishes I would just start sobbing, crying and crying, because I had this terrible feeling – I knew I couldn’t fix it.”

Paloma, the deceptively wide-eyed CIA agent de Armas played in last year’s No Time to Die, the film that closed the era on Daniel Craig’s brilliantly disgruntled take on James Bond. De Armas went straight from shooting Blonde under the stars on Santa Monica beach onto a red-eye, arriving at London’s Pinewood Studios to break more ground as the first Cuban actor to play a leading Bond woman. Her first takes, though, came out in Monroe’s whispery flutter. “I wasn’t ready to let her go,” she says. “In my heart I wish I’d had a few more days to say goodbye.” Still, she went on to deliver a firework of a performance, dispatching at least ten Spectre villains in the space of 12 minutes on a lavish replica set of Havana, Cuba.

De Armas, of course, was born in the real Havana, Cuba, in 1988, before moving aged three to Santa Cruz del Norte, a small, palm-filled town on the country’s northern coast where her father worked in a government office. Minus internet and social media, her childhood played out in the street. “You’re in a country where you don’t have much contact with the world, you’re kind of in a bubble,” she says. “But in some ways that makes you focus on life and friendships instead of all the noise. I grew up barefoot, running on the rocks by the beach, swimming. Me and my friends performed plays for the neighbours. I had a thing for climbing lamp posts and trees, and I was obsessed with rescuing cats and dogs from the street – every day I’d come back with a new animal and drive my mom crazy.”

When she was ten the family returned to Havana, a move that alerted her to the capital’s prestigious, and rigorous, National Theatre School, an arts complex with soaring architecture. De Armas badgered her parents to let her audition, but they tried to dissuade her at first from a dream with such slim chances of success. “Big mistake!” she says with a laugh. “I became determined.” After six long days of improvisation-based auditions she was among the handful of candidates who won a place, enrolling at 14 and often hitchhiking to get there each day. By 16 she had landed a lead role as a teenager longing to escape pre-revolutionary Cuba in the feature Una rosa de Francia – much to the irritation of her school, who disapproved of their students juggling acting studies with acting jobs. “But I didn’t care,” she shrugs. “In my opinion there was no better school than a movie set. So I did both – I would often fall asleep in class but I would catch up with what I missed.” Even at that age, her ambitions were reaching beyond the shores of her homeland; a few months before graduating, she made the decision to uproot her life and relocate to Madrid alone, courtesy of a Spanish passport through her maternal grandparents. It was a tactical move – had she graduated, she would have faced several years of national social service while watching her career stall. “My heart belongs to Cuba but I knew I had to get out of there to grow,” she says. “I was always aware of the very low ceiling that unfortunately Cuban artists and people in general have. I knew I had more to do, more to learn.”

When she arrived in the Spanish capital aged 18, de Armas barely knew anyone except her agent, but the gamble paid off: two weeks later she won the role of a fearless schoolgirl in the homegrown television series El Internado. Set in an elite boarding school teeming with murky secrets and ghoulish happenings, the show put her on the covers of teen magazines and made her famous nationwide overnight. At two series a year, it was an acting bootcamp, but also provided the still-adolescent actor with a surrogate family to assuage her homesickness. “Thank God I had that support network,” she says. “Being alone in Spain was really tough. It never crossed my mind to go back, but it was hard. I’d never been anywhere else before and it was a huge culture shock. To be honest, I just started eating candy, chocolate and donuts – everything I’d never had when I was younger.” She stuck with the series for three years, “and then I was like, OK, I’m not learning anything new”. By then, though, the financial crisis was biting in Spain and new film productions had ground to a worrying standstill. (“If no solutions are found, it could spell the end of many a promising career,” wrote the Spanish newspaper El País in a 2012 article entitled No Money, No Movies.) De Armas, already conscious of being typecast in teen roles, was getting restless. In 2014, an opportunity arrived that she grasped with characteristic tenacity. She was shooting Jonathan Jakubowicz’s Hands of Stone, playing the wholly undutiful wife of the hell-raising Panamanian boxing champ Roberto Durán, a part that transformed her into a hot-pink-Lycra-wearing mother of five. “De Niro was in it, and his agent came one day to a table read when we were shooting in Panama,” she remembers. “Afterwards they called up and said they wanted to represent me. I went back to Madrid, gave away all my stuff, packed a suitcase and left for Los Angeles.”

“Acting is my passion and what makes me happy, but it’s not who I am. That’s one of the reasons I left LA. I want to go there, see my friends, see my industry, but it’s not my life” – Ana de Armas

It was another roll of the dice: when she touched down at LAX, she had none of the profile she had built in Spain – instead she now faced auditions in a language she didn’t yet speak. “When I had my first meeting with my agent, I couldn’t say anything,” she says. “I just nodded and smiled. It was starting from scratch.” And yet she kept winning roles, showing up to auditions with her lines learnt phonetically. There was Eli Roth’s horror Knock Knock, in which she schools a beleaguered Keanu Reeves in stranger danger, then Todd Phillips’s black comedy War Dogs, based on the true story of two coke-fuelled Miami hustlers who made millions brokering shady arms deals for the US military in Iraq. As the girlfriend at home with the baby, de Armas made far more of her role than was on the page, but the language barrier was suffocating her usually expansive range: “In one of the scenes the director wanted to change the dialogue. It was one of the worst moments of my career. In front of the entire crew I tried and tried and just couldn’t do it. Todd went, ‘Forget it, just say it the way it was.’ I was so sad and frustrated because I couldn’t be myself, and I had no freedom as an actor. But it was a great reality check. I was like, ‘I have to do better. Work harder.’ And I did.” She signed up to a four month crash course in English and plunged back into auditions, continuing to make a name for herself – occasionally in films that didn’t deserve her – as an actor capable of rearranging our emotions with lived-in performances brimming with humanity.

Her breakthrough, though, came by way of a nonhuman role. In Denis Villeneuve’s ravishing, perpetually raining neo-noir Blade Runner 2049, she morphed from manga to geisha to Fifties housewife at the touch of a button as AI projection Joi. Despite her hologram’s ability to vanish inside a handheld console or stretch into a building-height advertisement, de Armas invested Joi with three dimensions and found tangible chemistry with Ryan Gosling’s sad-eyed, replicant-hunting gumshoe. The film won a couple of Oscars, put de Armas on genuine billboards and then on the red carpet, between Gosling and Harrison Ford. So it must have been a little exasperating when soon after, she was asked to provide an audition tape for a secret project that described her character in two words: “‘Latina, caretaker’,” de Armas says, rolling her eyes. “I was like, I do not have the energy, what is this?” She was in the midst of a gruelling threemonth shoot for Greg Barker’s biopic Sergio, pinballing from Thailand to Brazil to Jordan as the partner of peace-broker and human rights crusader Sérgio Vieira de Mello, the UN diplomat who was killed by a suicide bomber in Baghdad in 2003. “I said, you either tell me why this is worth it or I can’t. I passed on it twice because of that description. In the end, they sent me the whole script and I thought, oh shit! Right away I did an audition.” The film was Knives Out, Rian Johnson’s sly Cluedo game of a murder mystery, and her pivotal turn as the nurse to a millionaire crime novelist wove a critique of Trump’s immigration policies that subverted that cliché of a character description. It won her a Golden Globe nomination and the admiration of co-star Daniel Craig, who engineered the role in Bond that transformed her into one of Hollywood’s most in-demand actors.

Today she has a home in Havana (“My friends come over, we cook and play dominoes and what starts with some pork and rice and black beans ends up in a huge music jam session”) and an apartment in New York, shared with her boyfriend, Paul Boukadakis, and her two dogs, Salsa and Elvis. The latter canine is also now a movie star: when Dominik met Elvis, he was struck by his uncanny resemblance to Monroe’s own Maltese terrier, Maf (short for Mafia), given to her by Frank Sinatra the year before she died. And so Elvis was hired to play him – you can see the silky white terrier in the spectral, hazily lit scenes depicting Monroe’s bleary final hours behind the bougainvillea-laced walls of Fifth Helena Drive. When I mention struggling to sleep post that haunting ending, de Armas nods and her voice drops a little. “Those final scenes at her house – I know she was there with us,” she says. “We all felt it. And I think you can feel that in the movie.”

During her lifetime – and even her afterlife – Monroe was reduced time and again to a caricature of herself, despite her formidable talent and ambitions. Blonde’s intricate, knotty portrayal of her, de Armas says, sets out to reconstruct that diminishing narrative. “It’s the story of the double standards and hypocrisy of the culture we live in,” she says. “People obsessed over her body and shamed her for it. They criticise you for the same things they celebrate you for. There’s no way of winning. Marilyn was one of the first actresses who broke her deal with the studio and created her own production company, to make her own films. This was massive at the time. She wanted to be taken seriously. But no one was listening. They just wanted her to keep repeating the same thing forever.” In some ways, though, Monroe might help de Armas avoid that impossible trap herself. With Blonde, the actor who has already shapeshifted from lamp-post-climbing kid to Havana theatre student to Spanish teen star to Hollywood action heroine looks poised for another reinvention. “So many action roles have come my way from those few minutes in Bond,” she says. “If Blonde now brings me all these intense, dark roles, I will be happy. Blonde was hard on my head and hard on my heart, but I want to confront these issues. I want to talk about taboos and uncomfortable things and figure out how we really feel about them. And I think telling stories is a beautiful way to do that.”

Hair: Orlando Pita at Home Agency. Make-up: Francelle Daly at Home Agency. Set design: Piers Hanmer. Manicure: Megumi Yamamoto at Susan Price. Digital tech: Tadaaki Shibuya. Photographic assistants: Nick Brinley, Alex Hopkins and Shri Prasham. Styling assistants: George Pistachio, Molly Shillingford, Rosie Borgerhoff Mulder and Cornelius Lafayette. Tailor: Eliz Diratsaoglu at Lars Nordensten. Set-design assistant: Louis Sarowsky. Producer: Gracey Connelly. Post-production: Gloss.

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally now. Buy a copy here.