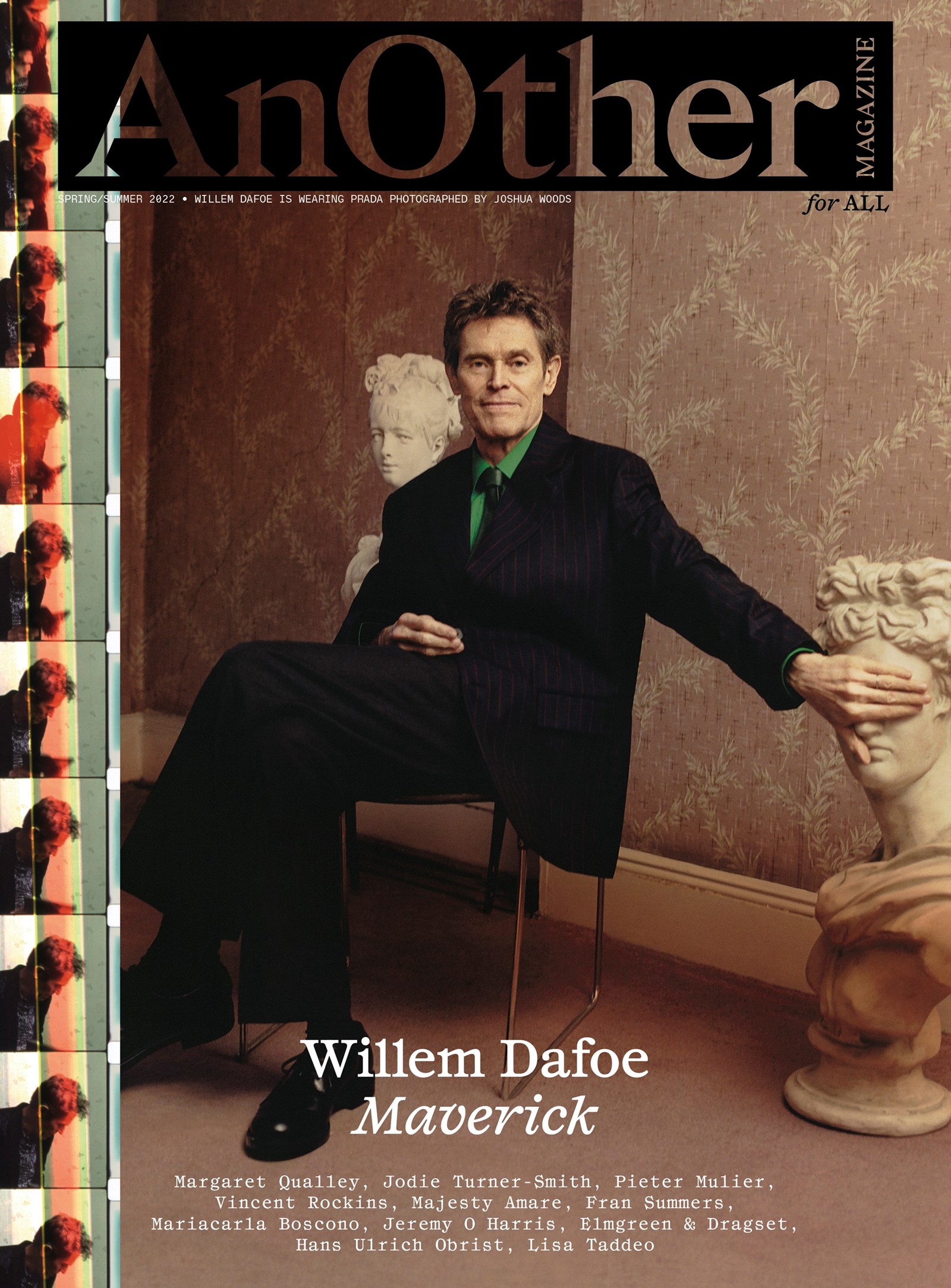

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine:

In 1979, tiny New York theatre The Performing Garage had 60 seats, a tin collection box and some of the most radical ideas in a grimy, broken-down city pulsing with creative energy. That year, Willem Dafoe was playing a foul-mouthed oil-rig worker, a heroin-addicted mother and a nun – all in the same play – when Kathryn Bigelow took a seat in the audience one night. The experimental works staged at the scrappy space in SoHo had more in common with the no-wave shows happening around the corner at the Mudd Club than with polite theatre uptown. Plundering all genres, they were loud and freewheeling, incorporating looping video projections, actors shouting over pre-recorded audio, technicians in full view, occasional nudity and, once, Dafoe in the role of a living chicken heart.

After seeing him onstage, Bigelow called the actor to ask if he wanted to be in a film. “I was still in the phone book then,” Dafoe says today, over Zoom from his home in central Rome. “I had to call up friends to find out what to ask for as a salary. I had no idea – I had no representation. My identity was totally as a downtown theatre actor living hand to mouth.” Bigelow cast him as a delinquent, leather-clad antihero in The Loveless, the tale of a nihilistic biker gang who ride into a Georgia backwater and set fire to its simmering tensions. It became Bigelow’s debut film (co-directed with Monty Montgomery), Dafoe’s first starring role, and today an artful cult oddity that makes one thing overwhelmingly clear: whether he’s dodging a shotgun or pouring ketchup over congealed scrambled eggs, Dafoe’s screen presence has been intact from the start.

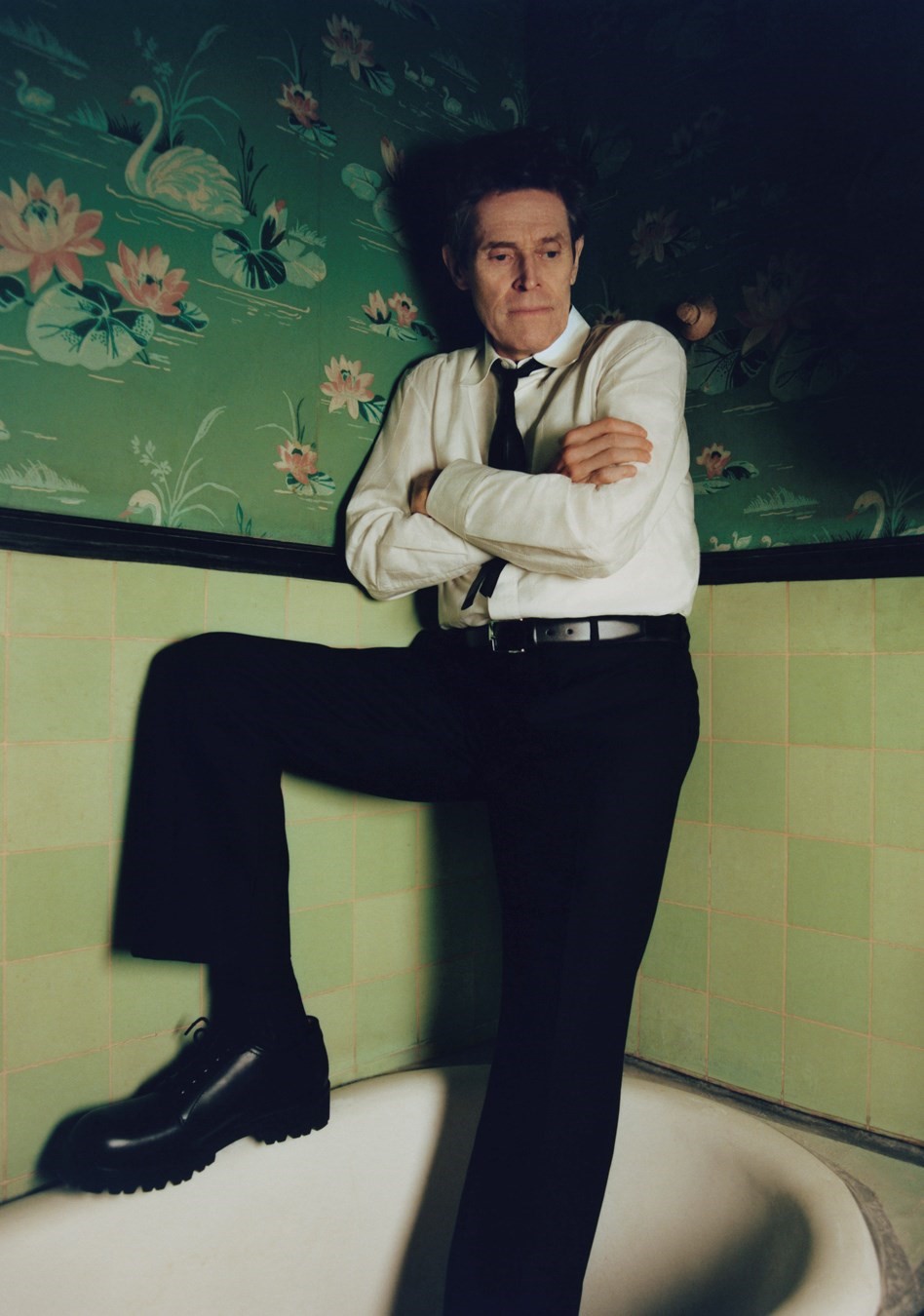

Even over an imperfect Zoom connection it’s easy to see how journalists get tangled up describing his face, its angles and hollows and meme-generating expressiveness: “a demiurge as rendered by a cubist” (The New York Times); “the pallidly beautiful embodiment of pure evil” (The Village Voice); “the boy next door, if you live next door to a mausoleum” (that was Dafoe himself). None of those descriptions captures his amiable charm in interviews – and as singular as he looks, in the four decades since his debut, the 66-year-old has carved one of the most versatile careers in cinema, uprooting his audience’s expectations again and again. His staggering 120-plus roles to date have encompassed oddball detectives, drug lords and unhinged hitmen, a giant alien and a manga god of death, Pier Paolo Pasolini and TS Eliot, a tropical fish and Jesus Christ. Dafoe’s versatility shows not just in his chameleonic powers, but his willingness to take a gamble and work outside his comfort zone. “I’m always nervous on my first day, but that’s good news,” he says in the ridged, textured voice that has become as distinctive as his elastic features. “It motivates you, fear. It’s what keeps you curious, keeps you trying to find new ways. If you accept fear, that’s a good practice for an actor to have – it’s a good practice for a person to have. You get used to being a little off balance. I don’t know whether I enjoy it – I’m like anyone, I like to be lazy and comfortable. But you know, that can kill you too.”

“Comfortable” is not a word often associated with Dafoe’s choices, but it might be a good description of Appleton, Wisconsin, the small paper-mill town he grew up in, a hundred miles north of Milwaukee. Pre Dafoe, Appleton’s two most famous residents were Joe McCarthy, ringleader of the communist witchhunts of the Fifties, and the magician and escapologist Harry Houdini. (A possibly unfair joke goes: “What was Harry Houdini’s greatest escape? Getting out of Appleton.”) Houdini was indeed long gone and Eisenhower was in office when Dafoe was born there in 1955, into an already-crowded family. The seventh of eight children, he was christened William, soon known as Bill, and later nicknamed Willem. His nurse mother and surgeon father both worked long hours, resulting in minimal supervision and family mealtimes – Dafoe credits his elder sisters with raising him. There’s a revealing childhood story he tells of shutting himself in a closet for two days to mimic the conditions of the Gemini astronauts orbiting Earth at the time: nobody noticed. Clearly attention would have to be sought elsewhere. “My place in this large family of eight kids definitely contributed to me becoming an actor,” he says. “It shaped me very much. I’m married to an only child [the Italian director Giada Colagrande] of a single mother – you have a totally different sense of your place in the world.”

Fittingly for someone who has played monsters better than anyone, Dafoe’s earliest film memories were the Frankenstein and Dracula reels his father brought back from work trips to Chicago. “We’d get these Super 8 edited features and I’d play them over and over in slow motion on a little Bell & Howell projector,” he says, “and charge the neighbourhood kids to watch.” You could argue that Dafoe’s first performances were surreal pranks – he once dressed up in a gorilla suit to picket Planet of the Apes at the local cinema. Appleton’s community theatre provided a more structured outlet for that mischievous energy, and brought him his first review – “This is a lad with a promising future on the stage,” announced the local paper of 13-year-old Dafoe’s turn in A Thousand Clowns. But in a family of medical professionals there was little thought that that afterschool hobby might become a career. “No, not at all,” he says. “Having said that, my family was very lively, great singers and dancers. The irony is, and it sounds a little coy but it’s sort of true, they’re all more talented than I am. I just worked on it.”

In 1977, after a few semesters at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and a stint with experimental troupe Theatre X, his ambitions led him to the logical destination for an aspiring stage actor. When Dafoe arrived in New York wide-eyed from the Midwest, the city was plunged in some of its darkest years. Virtually bankrupt, it was decaying and weed-ridden, with broad-daylight muggings and night-time blackouts (and a serial killer, Son of Sam, who took advantage of those blackouts). But its febrile atmosphere was causing an outburst of creative, cross-genre collisions, and after assuming he’d try his luck on Broadway, Dafoe found himself drawn instead to the grittier scene downtown. “I don’t want to be nostalgic, it was a rough time,” he says, “but I’m 20 years old, a kid from Wisconsin, not very sophisticated, not much of an education. I was living in tough areas, with people who had different problems and world views than I had grown up with. So it was a radical time for me. When I moved to SoHo it was a no man’s land, there was a bunch of old factory buildings gone belly-up. New York was in such bad shape people were taking over spaces to make their own work. So many musicians, painters, dancers that later became successful were all in the same room together then – at clubs, at the Kitchen or La MaMa. We were young and we weren’t thinking about tomorrow.”

That year he grafted as a stagehand at The Performing Garage on Wooster Street and encountered the explosive, uncompromising Elizabeth LeCompte, director of what would soon be christened The Wooster Group. The plays she helmed fused influences from vaudeville to Noh, and could feel white-knuckle reckless, as though being worked out in front of a crowd’s eyes. “It was a whole little world unto itself,” Dafoe remembers. “We were doing it for the love of it, not for a career. Every show we did felt like it was going to be the last, but that was the beauty of it.” He fell for The Wooster Group and LeCompte simultaneously and soon moved into the latter’s SoHo loft – in 1982 they had a son, Jack. Dafoe went on to appear in every production the crew staged for the next 27 years, despite the demands of a movie schedule that had him criss-crossing continents. There was just one stumble before his star began to rise: cast as a cockfighter in Michael Cimino’s 1980 western Heaven’s Gate, he laughed too loudly at a joke during a lighting set-up. Cimino, nicknamed “the Ayatollah” on that shoot, fired Dafoe on the spot. He’s too good-natured to relish the schadenfreude, but the film became a monumental albatross, floundering under bloated budgets and excessive retakes – hours lost waiting for the right clouds to roll by and weeks spent on roller-skating lessons for the cast. It came out to toxic reviews.

At first, screen villains came Dafoe’s way: a twitchy biker in Walter Hill’s neon-lit inner-city fable Streets of Fire, and then, in 1985, a homicidal, Ferrari-driving counterfeiter in William Friedkin’s brutally amoral neo-noir To Live and Die in LA. Friedkin’s vision of a city riddled with corruption, all blood-red skies and windlashed palms, climaxes with Dafoe’s character burning to death in a bonfire of counterfeit money. It was the first of many spectacular on-screen deaths that have included being impaled by a hoverboard, dissolved in a shaft of sunlight, and crucified. But it was the following year, and his slow-motion, bullet-addled demise in the Vietnam jungle to the sound of swelling strings and thudding helicopter blades, that marked Dafoe’s breakthrough, as the doomed Sergeant Elias in Oliver Stone’s searing indictment of the Vietnam War, Platoon. Stone upended the bad-guy narrative and cast Dafoe as the film’s moral anchor. “There was a soul in him, a gentleness that could radiate from those eyes,” Stone wrote in his memoir. The conflict in Vietnam had gnawed at the director since his own tour of duty, where idealism crumbled into disillusion, and he was determined his cast would emanate the gluey, bone-deep exhaustion he remembered. In 1986, they were dropped into the jungle for a gruelling boot camp – they dug trenches, slept in two-hour shifts and battled bamboo snakes and the night-time ambushes Stone surprised them with. Dafoe had to be medevacked at one point, after drinking river water downstream from a decomposing ox. The role put him on the cover of Time and gave him his first Academy Award nomination, for best supporting actor. “I still have my dog tags from Platoon,” he says. “I’ve got a little area in my office where things that have meaning for me pile up. Pictures, writings, poetry … I also have my parents’ ashes in a mason jar, so go figure.”

Michael Caine won that year for Hannah and Her Sisters, but Platoon brought Dafoe a new level of attention – specifically from Martin Scorsese, who needed an actor to play the son of God. He cast Dafoe in The Last Temptation of Christ and in 1987 he was performing miracles in the deserts of Morocco, in melting temperatures. “I really believe those difficulties are gold,” Dafoe says of his willingness to embrace whatever a shoot will throw at him. “They not only give you the authority but they create the stake. If something is hard, like you’re in the desert, that puts you in it. That will fuel the inner life and make the performing not feel like work, but like an adventure, like a life experience … Last Temptation was a big deal for me. That doesn’t mean I became a born-again Christian, but I started thinking about a spiritual life and forgiveness, and that triggered something in me.”

“I should just shut up and say it’s fun to play bad guys because it’s titillating to do bad things and not get punished for it” – Willem Dafoe

The film’s release prompted no forgiveness from the religious right; they unleashed hell. There were protests outside movie theatres, drive-by paint bombings and an arson attack that gutted a Paris cinema. The actor has never been afraid to provoke – most notoriously the boos and whistles of Cannes critics outraged at Lars von Trier’s psychosexual drama Antichrist, in which Dafoe gets his testicles crushed by a plank of wood. But the fact Last Temptation became a lightning rod for protest was something of a back-handed compliment to the actor’s earthy performance: he humanised Jesus, an apparently unforgivable blasphemy. (He also gave him a libido: in one scene Jesus imagines having sex with Mary Magdalene.)

But if Dafoe can humanise deities, he extends the same courtesy to his darker characters, often misfits whose dangerous menace has a streak of vulnerability. “Outsiders are the most interesting characters because they aren’t quite recognisable,” he says. “The audience has to work through how they feel about them.” His role last year in Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley, as a carnival grifter with a collection of pickled babies and a finely attuned ability to exploit the weakness in others, finds a muddy human space in a character whose actions are chillingly cruel. His more outlandish villains – who almost always go on to parallel meme careers – still have a textured, slippery nuance: it’s what made his odious, stubby-toothed hitman Bobby Peru in David Lynch’s Wild at Heart so indelibly disturbing. Dafoe credits the gruesome dentures Lynch made him wear – “Without those teeth who knows what I would have done? But the second I put them in, I knew exactly what to do” – but Lynch wrote that Dafoe was “a gift from God” in that role. Even when his characters are ripped straight from the speech bubbles of a comic book, like the cackling arch-nemesis the Green Goblin, Dafoe plumbs deeper waters. “I didn’t want to just be a device, that’s kind of a drag,” he says. “They’d probably pay you to do very little, but that’s not what I was interested in.” Instead, he threw himself into the part like a circus performer, switching between comedy and Shakespearean tragedy to craft what is generally considered everyone’s favourite supervillain.

“I should just shut up and say it’s fun to play bad guys because it’s titillating to do bad things and not get punished for it,” he says. “But the whole idea is you don’t want to see the world that way, or accept those kinds of categorisations. It challenges our idea of morality when you can find the most human aspect in dark characters. If a character does unsavoury things, you try to balance it with another aspect where it’s plausible that this guy can do bad things but still be your brother, your father, your lover.” Dafoe is now treasured for that ambiguity; he draws our imaginations out of well-worn grooves into unexplored territory. It has led him to build sustained and fruitful relationships with maverick directors who have a similar distrust of easy answers: Lars von Trier, Paul Schrader, Abel Ferrara – auteurs with vision and a personal stake in the stories they tell. If they have demanding reputations and unorthodox ways of working to get the demons in their heads onto film, Dafoe has always been game – it’s the pool he was baptised in at The Wooster Group.

It was Schrader – the gravelly voiced veteran of New Hollywood long preoccupied with sin and redemption – who wrote Last Temptation. The pair have made seven films together since, most recently last year’s murky crime drama The Card Counter, set between the twilight world of poker tournaments and Abu Ghraib. Their first collaboration was 1992’s Light Sleeper, starring Dafoe as a high-end drug courier soaking up nocturnal Manhattan from the back of a chauffeur-driven car, dropping off illicit deliveries to the city’s glass-and-art-filled penthouses as garbage piles up on the streets below. He’s one of Schrader’s classic troubled loners, lending an ear to his clients’ coked-up philosophies while being stalked by the feeling his luck is running out. Dafoe says it’s one of the roles he has felt closest to – perhaps the act of moving between so many different lives rang a bell. “There was nothing about him that was different from me except for what he did,” he says. “He was a lost soul, that’s not necessarily me, but I could have been him. If I didn’t find what I wanted to do and I got into that line of work … I understood him.” Dafoe shadowed a dealer for three weeks prior to shooting, which must have been a little bizarre for the customers. “I got to know the business, the clients. He was different to my character – he was gay, had different music taste, lived in a different part of town, but he taught me a lot.”

That commitment to performing the actions of his characters is often central to Dafoe’s approach. He doesn’t do method or spin intricate backstories, but melts into his roles by rooting himself in their physicality. That meant skinning his own wallaby as a mercenary in Daniel Nettheim’s The Hunter (Dafoe puts his lack of squeamishness down to a stint as the janitor of his father’s medical building when he was a teenager). And to step into Van Gogh’s battered shoes in 2018 for Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate, he got paint under his fingernails during art lessons with Schnabel himself – they first crossed paths in the New York nightlife of the Eighties. “Painting literally changed how I see things,” he says. “I was doing it in Van Gogh’s clothes, looking at the same things he looked at. It was thrilling.” It’s an electrifying performance: Dafoe unearths the famous name from the calcified cliché, stripping away the layers of dust and bad merchandise to reveal an unmediated glimpse of the world through the artist’s eyes: raw and alive, flooded with yellow light, tugged by the swells and currents of madness. “I loved that film,” he says. “It was a little channelling job. He’s in the air, he’s in the soil in Provence.” In 2019, it gave Dafoe his most recent Oscar nomination and he’s kept all the canvases he painted during filming, “even the bad ones”, he says with a smile.

He played another late icon, Pier Paolo Pasolini (they look uncannily alike), in Ferrara’s 2014 portrait of the provocative Italian filmmaker’s final 24 hours and shocking, grisly death. Ferrara, the irascible director whose career has spanned porn to grindhouse to studio films, is exactly the kind of partner in crime Dafoe gets a kick out of – a live wire who wills his work into existence. Their friendship stretches back to a late-night meeting in a Canal Street bar that resulted in the woozy 1998 cult movie New Rose Hotel. They’ve made five feature films together since, including 2019’s Tommaso, shot on a shoestring in Rome. In it, Dafoe plays an American director transplanted to the city, living with his young wife and child, attending recovery meetings and sporadically pierced by sudden and terrible visions. It’s not autobiographical, but it feels like their most personal film: at one AA meeting Dafoe’s character shares a rock-bottom memory from a drug-fuelled Miami shoot that seems pulled straight from Ferrara’s own battles with substance abuse; at another he teaches an acting class with musings that align closely with the actor’s own methods. (His character also practises some gravity-defying yoga, as Dafoe has done every morning for years, though he prefers not to harp on about it.) The pair’s ongoing collaboration is emerging as one of cinema’s most stimulating actor-director partnerships – today they’re neighbours in Rome and Dafoe is godfather to Ferrara’s child.

The actor has split his time between New York and the Eternal City since meeting his wife there in 2004, while shooting his role as Klaus, the comically loyal shipmate in tiny blue shorts in Wes Anderson’s offbeat gem The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. Dafoe is now an Italian citizen and speaks the language of his adopted country. “I’m one day back here and I’m in heaven,” he says, recently released from a rapid-fire round of Spider-Man: No Way Home junkets. “There’s a sense of beauty and impermanence and history that I love. I like the people so much. I don’t want to sound like a rube – it’s a broad statement – but they’re empathetic. Americans like a winner. Italians consider people that have lost in a different way. In more puritanical societies, which probably includes where you’re from and where I’m from, it’s, ‘If they fall, keep ’em down, because it’s their fault.’”

Dafoe and Colagrande married in 2005 (she will next direct him in the noirish spy thriller Tropico). That brought his epic run with The Wooster Group to a close, but his theatre work has continued elsewhere: in 2011 he was the shapeshifting storyteller of Robert Wilson’s The Life and Death of Marina Abramović, with ghostly make-up and fiery hair; and Abramović later asked him to star in her seance-like experimental opera 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, in which the pair morph through operatic death scenes – in one Dafoe strangles the artist with two gigantic, coiling snakes. They will reprise the performance this May at the world’s oldest opera house, the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. “I probably get more inspired by art, performance, dance, than film actually,” he says. “Sometimes I see a painting and I don’t have the language to say why, but it opens me up to wonder. You come to it, rather than it coming to you. I think that expresses something about my taste in movies too.”

Dafoe has often said he feels more like a dancer than an actor, trusting his senses and his body’s intelligence as a dancer might. On screen he has a lithe physicality – there’s a tracking shot in Sean Baker’s The Florida Project in which Dafoe wrestles the wallet from a shady character that is so gracefully accomplished it might be a choreographed dance, though it took him barely two takes. That film is another example of the actor’s undimmed pleasure in exploring new territory – as well as the older generation of cinematic rebels, he has sought out the new vanguard of original thinkers. There are plenty of film stars who would balk at jumping on board with less-seasoned directors (and less-bountiful budgets). Dafoe has no such qualms if the work is good, and those young directors have returned the favour with roles that have inspired some of his best performances. After seeing Tangerine, Baker’s iPhone-shot slice of life in LA’s transgender community, Dafoe volunteered to star opposite non-actors as the besieged manager of an ice-cream-coloured motel near Disney World in the director’s The Florida Project. The quiet integrity Dafoe brought to his role as a guardian of wayward families on the brink of eviction was a reminder of what an unselfish co-star he has always been. (See his understated, straight-arrow federal agent to Gene Hackman’s bombastic southern charmer in 1988’s Mississippi Burning.) His dedication – forged in theatre – to working for the group allowed the film’s nonprofessionals to breathe. “I didn’t think about playing scenes,” he says simply, “I thought about being the best manager of a hotel I could be.”

That film delivered him another Oscar nomination in 2018, the same year he began working with Robert Eggers – he had contacted the director after seeing a poster for his candlelit indie horror The Witch and spontaneously walking into a cinema to watch it. Eggers created The Lighthouse, a nightmarish tale of screaming seagulls, ocean spray and maritime superstition with Dafoe in mind, and he delivers an acting masterclass as a loquacious, weather-beaten wickie trapped with Robert Pattinson in briny isolation. (Dafoe holed up in a creaky fisherman’s cottage in Nova Scotia and learnt to knit like a 19th-century New Englander during the storm-tossed shoot.) Where Dafoe leads, others follow: he and Eggers reunite again this spring in The Northman, a lush, 10th-century saga steeped in Norse myth, this time with a $60 million budget and a cast including Nicole Kidman and Alexander Skarsgård. Dafoe’s role sounds perfectly appropriate: he plays a jester, the figure who challenges the court and its hierarchies under the guise of performance. “The artist is supposed to challenge society, and that includes the jester in this case. But – he pays for it!” says Dafoe. “I’m a real cheerleader for Robert [Eggers]. He’s from the theatre – when I met him I felt very close to him.” He’s just finished shooting with another former theatre director, the gleefully unpredictable Yorgos Lanthimos, who cast Dafoe as a Frankenstein-like scientist in Poor Things, his follow-up to The Favourite. The Greek auteur is notorious for eccentric rehearsals that have involved asking actors to recite lines while fighting invisible force fields or behaving like human noodles. “It helped to liberate the actors from their shtick and find new ways,” Dafoe says of the process. “Let’s just say I wasn’t disappointed by the specificness of his vision. I think of Yorgos and it puts a wry smile on my face.

After four Academy Award nominations to date, this year Dafoe will be receiving that enduring symbol of movie-icon status, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It’s doubtful he’s been losing sleep over it, but it’s odd that a household name like his wasn’t etched into the pavement years ago. In part, that might be Dafoe’s own cleverness at hiding in plain sight – all the better to disappear into his roles. He’s the A-lister who has slipped the leash that moniker entails and crafted a career on his own terms, switching from blockbuster to indie to experimental opera, often in the same year. It’s part of his considerable charm that he will commit with his every fibre to each project; Dafoe is not an actor who phones it in. The result is that everyone has their own favourite version of him – for every Florida Project fan, there’s someone with a special place in their heart for his cross-dressing FBI agent in The Boondock Saints.

Francis Ford Coppola once asked Dafoe to write an essay, Why Act in Theatre?, for his Zoetrope: All-Story magazine. It’s a question that might have returned a rather ponderous answer. But Dafoe’s caught at the joy he finds in performing, onstage or on screen. “It engages the high-minded seeker and simultaneously satisfies the crude exhibitionist in me,” he wrote, “as does dancing, dressing up for Halloween, telling jokes, sex, reading aloud to someone, doing imitations, smiling at strangers, playing with animals, flirting, playing charades, singing on a bus.” In his seventh decade, one of the world’s greatest actors is on a roll, burning as brightly as the twentysomething kid Kathryn Bigelow spotted onstage. He has brought the anarchic spirit of the downtown scene onto the big screen and shifted the conversation in the process, both his heroes and villains questioning the way we think, and watch. Many actors harbour, for better or worse, a yearning to direct. Dafoe is not one of them: he found his calling in his teens, and he’s still fired up about its possibilities. “If you’re open to experience, and it doesn’t have layers of ego over it, hopefully people will see that and say, ‘I wonder whether I could do that?’ Or, ‘How would I feel?’ And that brings you on the trip with me,” he says. “That’s the pleasure of telling stories. It challenges how we live and sometimes proposes other ways to live.”

Hair: Mustafa Yanaz at Art and Commerce. Make-up: Amy Komorowski at The Wall Group. Set design: Alice Martinelli at MHS Artists. Photographic assistants: Nicolas Padron, Ahmed Alramly and Elizabeth Borrelli. Styling assistants: Jordan Duddy, Isabella Kavanagh, Marley Cohen and Lilly Nasso. Set-design assistant: Mattia Minasi. Producer: Jennifer Pio. Production manager: Alex Frischman

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale here.