This article is taken from Issue 9 of Wallet:

Robin Givhan is the senior critic-at-large for The Washington Post, and has contributed to several important magazines, in print and online, amongst them The Daily Beast, Newsweek, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Essence. She has also contributed to many books on fashion and released The Battle of Versailles: The Night American Fashion Stumbled Into The Spotlight And Made History in 2016 and Everyday Beauty in 2020. Givhan is the only fashion writer who has been awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Criticism.

Elise By Olsen: How did you get into fashion in the first place, and what made you want to become a professional fashion critic?

RG: Robin Givhan: My interest was in journalism and writing. I went to graduate school for journalism, so I really didn’t have a particular interest in fashion. After my first job I was a generalist writer at a publication, and I found it hard to not have a specialty of my own. When the person who had the job of fashion editor at the publication moved on to a different job, I raised my hand and applied for the job, mostly because I really wanted an area of specialty. That’s essentially how I ended up writing about fashion.

EBO: Seems we were lucky it was the fashion editor that moved on. Your generalist background might explain how you have tackled “fashion” from both social, formal, economic, and political angles. What is your basic interest – or question – that makes you return to writing about fashion, as opposed to something else?

RG: I have a new title, which is senior critic-at-large, which has been the case since September 2020. In many ways I had actually expanded what I’m writing about to formally include politics, race, and art, of which fashion is sort of one. I can say that one of the reasons why I covered fashion for so long, and one of the reasons why I wanted to continue to have a piece of it under my new title and in my portfolio, is because I think fashion is a place where so many different aspects of the culture intersects, and in a way that’s incredibly personal. Unlike film, music, or literature, we quite literally wrap ourselves in fashion. And we can’t really do without it.

“Criticism in arts and music generally tend to be more of an accepted form of criticism in the more popular imagination. A lot of that is because fashion is still perceived as a place for women, with a fascination with women” – Robin Givhan

EBO: Do you think criticism is a more respected and established discipline in other cultural fields such as art, film or music?

RG: Criticism in arts and music generally tend to be more of an accepted form of criticism in the more popular imagination. A lot of that is because fashion is still perceived as a place for women, with a fascination with women. There’s some sexism involved in the way that fashion criticism is sometimes perceived. That said, I also think that, particularly in the newspapers in the States, there was a much more vigorous coverage of the fashion industry because there were so many smaller regional newspapers that covered fashion as a business, and as something that was used as pleasure. As those newspapers have really had to cut back, we really lost a generation of fashion reporters. That’s unfortunate. A lot of writers who are interested in fashion have had to find alternate ways of being able to write about a topic that intrigues them. Some of them do it online, and there’s certainly terrific fashion reporting there, but the power of magazines – whether in print or online – has also been heightened. The magazines generally have a mutually beneficial relationship with fashion that’s made criticism more of a challenge.

EBO: That relationship is something we really want to focus on in this issue. How do you compare or distinguish between fashion coverage, versus analytical or critical journalism?

RG: I don’t. I think they’re one and the same. Fashion coverage is analytical, critical, objective journalism, or at least it should be.

EBO: How have the conditions around fashion criticism changed through your very extensive experience?

RG: The way in which the information is disseminated has changed, certainly, but in my mind, fashion reporting and fashion criticism should still be handled with the best journalistic principles. You want to report and make sure that you provide context and that your criticism is fact-based. Obviously criticism is a point of view, but to me, the best criticism comes from showing your work, you explain to readers how you’ve gotten to your opinion. And you put it into some broader context. I don’t think anyone particularly cares if someone says “I thought X collection was great”, or “I thought X collection was bad”, unless they have the ability to explain why they think this collection was particularly bad, at this moment, under these circumstances, presented in this way. There are many collections that I’ve written about in a very positive way that I personally would never want to wear, and with clothes that don’t appeal to my personal aesthetic, but that I still believe are really powerful, interesting collections that helped move the fashion industry forward.

EBO: So, the principles of fashion criticism are the same today as 20-30 years ago, but the tools or outlets have changed?

RG: Yeah, I think the way in which people get their criticism out there and the way in which people consume it certainly has changed. The speed in which they consume it has changed. Yet I don’t think that the technical changes made critics not adhere to good journalism. Nor do I think that it made critics voice their opinion without any substance backing it up. I think there’s certainly a whole new category of people chronicling the fashion industry, and I would say that is the impact of influencers. I think there’s certainly a difference between influencers and critics, even though both of them might use social media or Instagram as the way in which they get their point across.

“A good critic recognises that the point of their work isn’t to make it personal, but it’s to try and be constructive” – Robin Givhan

EBO: How would you describe the relationship of the fashion industry and criticism today?

RG: There are some designers who really do value thoughtful criticism, and use it as a tool to think about their work and the way that it relates to people once it sort of leaves their orbit. A good critic recognises that the point of their work isn’t to make it personal, but it’s to try and be constructive. Not necessarily constructive for the designer, but constructive for the reader, to help the reader make sense of all of their daily dosage of information that’s coming at them. In the best of circumstances that relationship between the critic and the industry, while it certainly can be tense and has a lot of give-and-take, can be really productive.

EBO: You are employed by The Washington Post, one of the few broadsheets that still reign today, and that, rarer yet, privilege fashion criticism. How do you perceive their role in the industry of today – where technology, corporatisation, and changing print publishing practices are turning the tables of the industry once again?

RG: I think I’m really lucky to be at The Post, which is a place that’s still expanding and growing. Its coverage is reflecting the human experience, as cliché as that might sound. It’s a really wonderful thing that fashion continues to be something that’s part of what The Post wants covered. I’ve said many times before that I think it’s a very great thing that The Post has never had a separate fashion section, but fashion coverage was always part of the Style section, which has coverage about fine art and music and literature, and all of these things bump up against each other in a way that I think mimics the way that fashion today exists in the world. In some ways it’s been a bit of a detriment to the way that the more average person will relate to fashion, because fashion refrains itself as very rarefied and that’s excluded a lot of people who have an interest in fashion, and who probably would consume it more vigorously if they felt more welcomed by both the industry and the coverage of it.

EBO: You also write about plenty of other things for the Washington Post – do you distinguish between your fashion and non-fashion pieces? And do your editors?

RG: My experience with the editors is that no, they don’t. I probably approach every story with the same beginning which is what peaks my interest at the start, how do I learn more about this, who do I meet to talk to, what point of view should I be taking into consideration, what don’t I know, what presumptions do I have that I might want to test to see if they’re legitimate. Every story is an opportunity to indulge my curiosity. One of the reasons why I welcomed being able to expand more fully into other areas of coverage is that it was an opportunity to really increase my learning curve.

EBO: Fashion journalism, perhaps especially in traditional magazines, has been in a poor state for a while and is still far from ideal; visual content often trumps textual content, in-depth stories are branded and low-key based on commercial interest. Do you think fashion criticism will have a resurgence soon – perhaps with the new generation? Or are we all doomed?

RG: [Laughs.]. I really don’t know. Maybe? There certainly are people out there who are looking at fashion coverage and who are really hungry for something that feels like it’s there, but also feels like it has a certain amount of scepticism – that it’s not quite so cheerleader-ish. And there are certainly people out there, and Diet Prada are one of them, who really want to hold the industry to account. And want to do it in a way that gives the fashion industry the respect, and holds it to standards that are similar to other industries. Rather than dismissing fashion or being hyper-critical, I think to expect that fashion faces its responsibilities when it comes to things like diversity, inclusivity, sustainability, transparency – things that a lot of people expect from other industries – says that you see fashion as just as influential and valuable as these other industries. You criticise things that you care about constructively.

EBO: You always avoid polemics, yet you do take the privileges of judgment – of taste – seriously as a critic. What’s ‘good’ and what’s ‘bad’ in your book? How do you form your opinions, and why is it important that a critic has opinions?

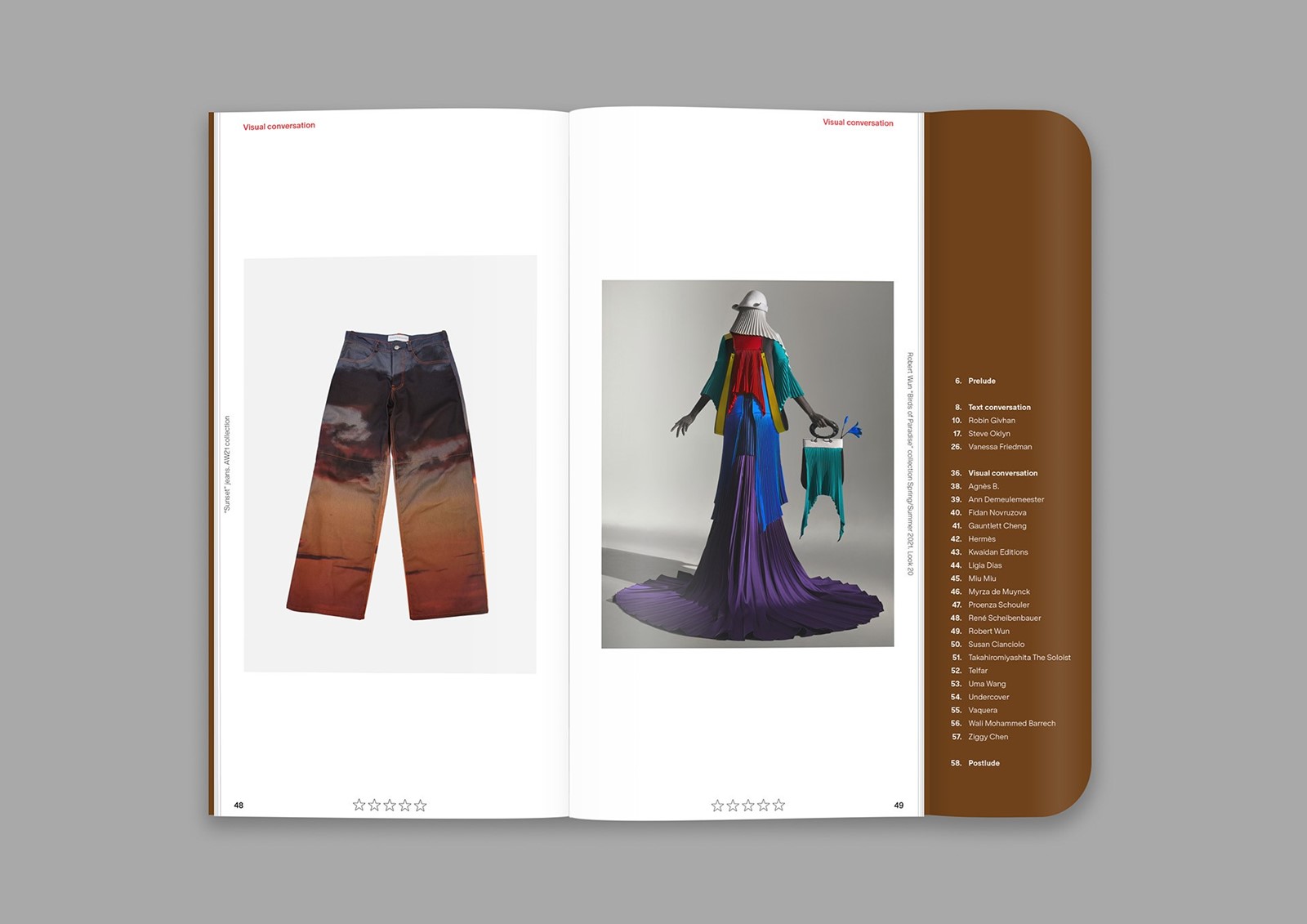

RG: The definition of a critic really is someone who is looking at something from a particular perspective and through a particular lense. To answer the question of whether something is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ you really need a lot of context. I don’t think that you necessarily are using the same metrics to critique a collection from a brand like Chanel – which has an incredible legacy and frankly has a bottomless pit of resources – and a collection from a brand that’s two years old and is still not profitable or remains underfinanced. You go into both of those collections, and recognise the advantages and disadvantages. That said, I still believe that even if you are a brand that’s two years old and underfinanced, if you’re going to present a collection you really need to know what it is that you want to say, you need to have a point of view. You’re sort of stepping up to a microphone and you should know what you want people to take away. In many ways I look at collections and I consider what it is that the brand has set out to do, and whether or not they’re successful at that.

“It’s my place ... to represent the reader to the fashion industry” – Robin Givhan

EBO: Who are your favourite current voices in [fashion] criticism, and how important are these to your work?

RG: That’s a hard question, in part because when I write show reviews and things like that I make a point of not looking at another critic’s work, or if they’ve written the same that I’m going to be writing. I certainly value being able to have that post-show conversation with colleagues when you’re still digesting things, but I probably only really look at work from non-fashion critics more than I read other fashion critics. I feel like the former helps me expand the way in which I think about fashion by helping me connect dots.

EBO: In a fashion world where it seems as if you are either praised or cancelled, is it the traditional fashion critic’s duty to mediate nuance?

RG: Yes! The value that a good critic can add to the conversation is well-centered thoughtfulness. Fashion is definitely a culture that is very connected with speed, and that’s something you need to take into the consideration – it’s rare that you have a couple of days to decide whether or not you’re going to write about it. There’s value in waiting a bit and sitting with something for a while before you react, because often the first reaction may be full of emotion, but it may not be full of intellectual precision. At least for me. It takes me a bit before I feel that I can put my thoughts into coherent sentences. I’m also very cognizant that words matter, and I want to be able to weigh my words precisely, I want to make sure that I have chosen the right word to convey my understanding of something.

EBO: Lastly, what changes would you like to see in fashion?

RG: I don’t consider myself part of the industry. The fashion industry is something that I write about, so I don’t know if it’s my place to tell the fashion industry how it should change. It’s my place to assess where the industry is and where it’s going, and to explain to readers what those changes and what that direction means for them. And also to represent the reader to the fashion industry.

Wallet, Issue 9 is out now.