Will the circular economy, advances in textile technology and a new generation of designers turn fashion’s environmental impact around?

Living through Covid-19 has made us focus on what really matters, with many in the world of fashion ranking the planet highly on that list. Both the fashion and luxury industries have suffered financially during the pandemic, with sales down as much as 30-40 per cent globally according to Forbes. Pre-pandemic, overproduction had already become a problem for the industry, with lockdowns providing a potential opportunity to reset.

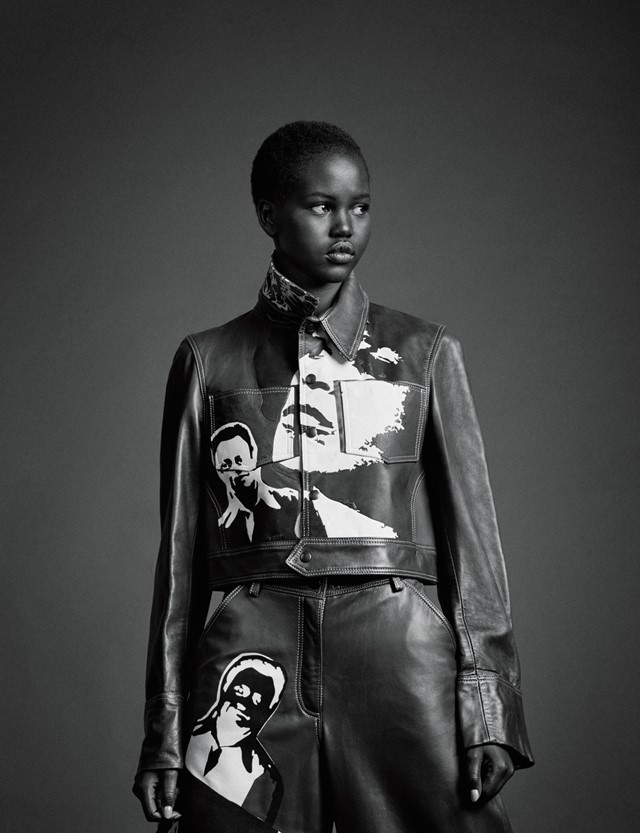

Rising London designer Tolu Coker, whose upcycled-leather jacket was featured on the cover of AnOther Magazine Autumn/Winter 2020, thinks fashion has been moving too fast for a long time. “The pace of it alone makes it inherently unsustainable,” she tells AnOther. “One silver lining of the global lockdowns was forcing the world to slow down and take time to think not just about ourselves, but the world around us and reprioritise values and ways of living and working.”

Cracks had already begun to show in the wholesale and seasonal models, with supply outpacing demand, leading to waste rather than profit. Esteemed department stores Barneys and Neiman Marcus went bankrupt before and during lockdown. Then, brands from Gucci to Saint Laurent and more turned away from the pressurised schedule of up to five collections per year, tightening their focus to fewer shows and slowing the pace.

One alternative business model includes pre-ordering by consumers. For example, Telfar Clemens’ label, Telfar, whose social fan base allows the brand to bypass the wholesale stockist system with direct-to-consumer sales. Telfar sells their wildly popular shopping bags and apparel though limited drops, with occasional opportunities to pre-order, fulfilled within six months, which eliminates stock waste and reduces carbon footprint as goods ship from factory to consumer, cutting out intermediary journeys.

Emerging designer and CSM alumni Bradley Sharpe, known for his 18th century-inspired creations made from festival goers’ unwanted tents, is launching his new season via pre-order only. “I don’t want to just make a batch of pieces for them not to be bought by anybody,” he says. “As naive as it sounds – I want to make pieces for people who care about them and hopefully will look after them”.

While the industry overall suffered, according to Dio Kurazawa, co-founder of The Bear Scouts, an organisation providing innovative solutions to promote circularity, biodiversity and up-cycling for supply chain, brand and retail clients, some sectors have been impacted more than others. “We’ve not seen demand for responsible products waiver during the pandemic,” he says. Although “the economic impact of the pandemic [hit] brick and mortar-heavy brands and retailers”, Bear Scouts’ clients like London concept store LN-CC, who stock Alexander McQueen and Balenciaga, “have maintained a strong responsible fashion focus and have enjoyed a highly profitable year, selling mostly online.”

In truth, sustainability has steadily been infiltrating the fashion mainstream for a while, with established brands such as Stella McCartney, Burberry, Alexander McQueen and Gucci taking the climate crisis seriously and setting goals regarding recycled materials, sustainable sourcing, and a route to carbon neutrality.

Meanwhile, making use of the billions of clothes already in existence has never been more important, to reduce landfill waste and maximise garment lifespan. Recommerce via Vestiaire, The Real Real, Depop and Rebag, are growing in popularity, adding a glow of environmental virtue to the relative affordability of pre-loved fashion. Farfetch offers a range of vintage items and will also accept your old clothes via Thrift+ in exchange for vouchers. London fashion destination, Selfridges, has added ReSelfridges, in-store and online to keep up with the secondary market in luxury pieces. Online vintage selling has become ever cooler and more specialised, with the likes of NYC boutique What Goes Around Comes Around, and Re-See Paris’s rare Hermès and YSL treasures selling briskly online.

For garments that don’t survive fashion’s changing vicissitudes, upcycling has undergone a renaissance. It’s now possible to buy upcycled luxury jeans; ELV denim, streetwear; Zero Waste Daniel, and fur coats; Nereja among many other products. Online fashion service Reture will take your existing garment and either re-dye, embellish or re-engineer it for you on demand. What can’t be reused as clothing does not have to go to landfill, with French enterprise Fab Brick creating colourful building materials from waste textiles.

Brands like Gucci make use of recycled textiles in their collections, using a scheme called Re-Verso. The Bear Scouts help the fashion house source the material to be recycled, usually pre-consumer, in other words offcuts and waste from factories. Meanwhile, Stella McCartney’s cashmere pieces are made from re-engineered Re-Verso cashmere rather than virgin fibres, with cashmere goats being one of the most resource-heavy herds to farm.

Responsible methods are also integral to Bradley Sharpe’s line, who’s sourcing nylon [a material originally made from oil] made from landfill waste. “I’ve just sampled a dress made entirely from recycled industrial fishing nets,” he says.

In a futuristic plot twist, new collections are being designed with either future resale or recycling in mind. “Brands like Ganni have heightened their focus on circularity or closed loop solutions, which involves teaching their designers to design based on future re-use,” says Kurazawa. “Brands must consider their fabric choices based on limitations for post-consumer recycling to make circularity achievable.” Ganni also uses blockchain technology which ‘tags’ the material, to help with circularity throughout their supply chain, he explains.

In September, Alexander McQueen, who’ve explored various sustainable policies, relaunched MCQ as a fashion line with a difference; every garment is tagged with blockchain technology to prove authenticity. A new “innovative and collaborative platform, MYMCQ, which integrates fashion and technology, allows consumers to interact and engage via a tag located in each garment” as part of a drive to foresee fashion pieces’ resale potential and facilitate trading among the community of the peer to peer platform. Alexander McQueen has also become the first house to collaborate on Vestiaire Collective’s new ‘Brand Approved’ programme – the brand will contact a small number of clients to offer the chance to sell their Alexander McQueen pieces, which will be exchanged for in-store credit.

A generation of brands from Marine Serre, who uses upcycled and recycled fabric; to Londoner, Priya Ahluwalia, who explores the potential of vintage and dead stock clothing by giving existing textiles and traditional techniques a new life, and Mary Benson who also upcycles vintage deadstock – have all built sustainability into their business model since launch. Kurazawa comments that, despite the faults inherent in the industry, “the generation of young designers and innovators finding ways to be inclusive, considerate, caring and loud about it, fills me with so much hope”.

Tolu Coker creates her collections from deadstock materials. “Denim, lace and leather have been the main materials I’ve explored, but I’ve been extending this to looking at other cottons, linens and even hemp,” she says. “Most of my materials are sourced from waste across factories and produced in-house or small London factories.” She adds; “Not only does this mean you can trace back the production line to ensure things are made ethically, but it builds a genuine community.”

In future collections, including her forthcoming looks for Autumn/Winter 2021, Coker will reimagine her signature prints in woven form, “reducing the amount of materials“ she uses. “I’ve been looking at artisanal weaving techniques to create patterns and designs in denim,” the designer explains. Coker also explored “incredible dry-indigo denims, drastically reducing the amount of water used in the dyeing process” with a Spanish factory.

Technology is the vehicle by which fashion graduate Jisoo Jang of CSM is advancing sustainable fashion, having pioneered a zero-waste design out of laser-cut washable paper, producing ripples throughout Instagram when it debuted. Her graduate collection also explored the use of bioplastics with gelatine and jesmonite for accessories. Now back in Korea waiting for travel restrictions to lift, Jang is “developing some recycled designs out of daily waste in a fun way” as well as developing the laser-cut paper gown into a wearable garment.

Meanwhile, French designer and winner of the Métiers d’Art de Chanel for the 35th Festival of Fashion Hyeres (2020), Emma Bruschi, looked back rather than forward in time to create men’s and unisex fashion from crocheted and embroidered straw. Bruschi was inspired by the landscape of her rural French homeland and learned straw weaving by visiting the Straw Museum in Switzerland. She said: “I was fascinated by this raw material with so much delicacy. I’m still really passionate about it.” She added; “all of my production is made by me in my workshop and with French craftsmen like basket makers, Blacksmiths, wool hand-spinners and glassblowers.” During lockdown, Bruschi experimented with materials even closer to home, like papyrus from her garden. She’s also planted rye to produce her own straw, and is looking forward to her first harvest.

Looking ahead to beyond 2021, it’s likely that the urgency of the climate crisis will increase consumer and legislative pressure on more brands to become sustainable and faster. Techniques in the pipeline include; various materials being ethically grown in laboratories, from cotton to bacterial leather. Plus, greater prominence of 3D shoe printing, 3D garment weaving, according to Kurazawa, as well as what Emma Bruschi describes as “wonderful materials which have proven themselves for millenia, which we’ve forgotten how to produce but that can be rehabilitated”.