The monogram of Catherine de Medici, the 16th-century queen consort of France, was an entwined pair of C’s. Sound familiar? It punctuates the stone-carvings of the Château de Chenonceau, a castle that Catherine had wanted but that her husband, Henry II, gave to his mistress Diane de Poitiers – perhaps giving the palace its nickname, the ‘Château des Dames’. “It was designed and lived in by women,” wrote Virginie Viard, introducing her second Métiers d’Art collection for the house of Chanel. “It is a castle on a human scale.”

Let’s unpack that history a little, before we unpack that statement. Gabrielle Chanel herself was inspired by the renaissance, despite the marked simplicity of her designs. “She so admired renaissance women,” says Viard. “Her taste for lace ruffs and the aesthetic of certain pieces of her jewellery come from there. Deep down, this place is a part of Chanel’s history.” “Magnificent simplicity” was a phrase Chanel herself used to describe the women of the renaissance – and their dresses liberally studded with pearls, then a symbol of purity and virginity (look at Elizabeth I as prime Anglophile example) have an obvious relation to Chanel’s aesthetic. That said, Chanel herself probably related more to de Poitiers than de Medici – she was, after all, the mistress to Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, once purportedly saying: “Everyone marries the Duke of Westminster. There are a lot of duchesses but only one Coco Chanel.”

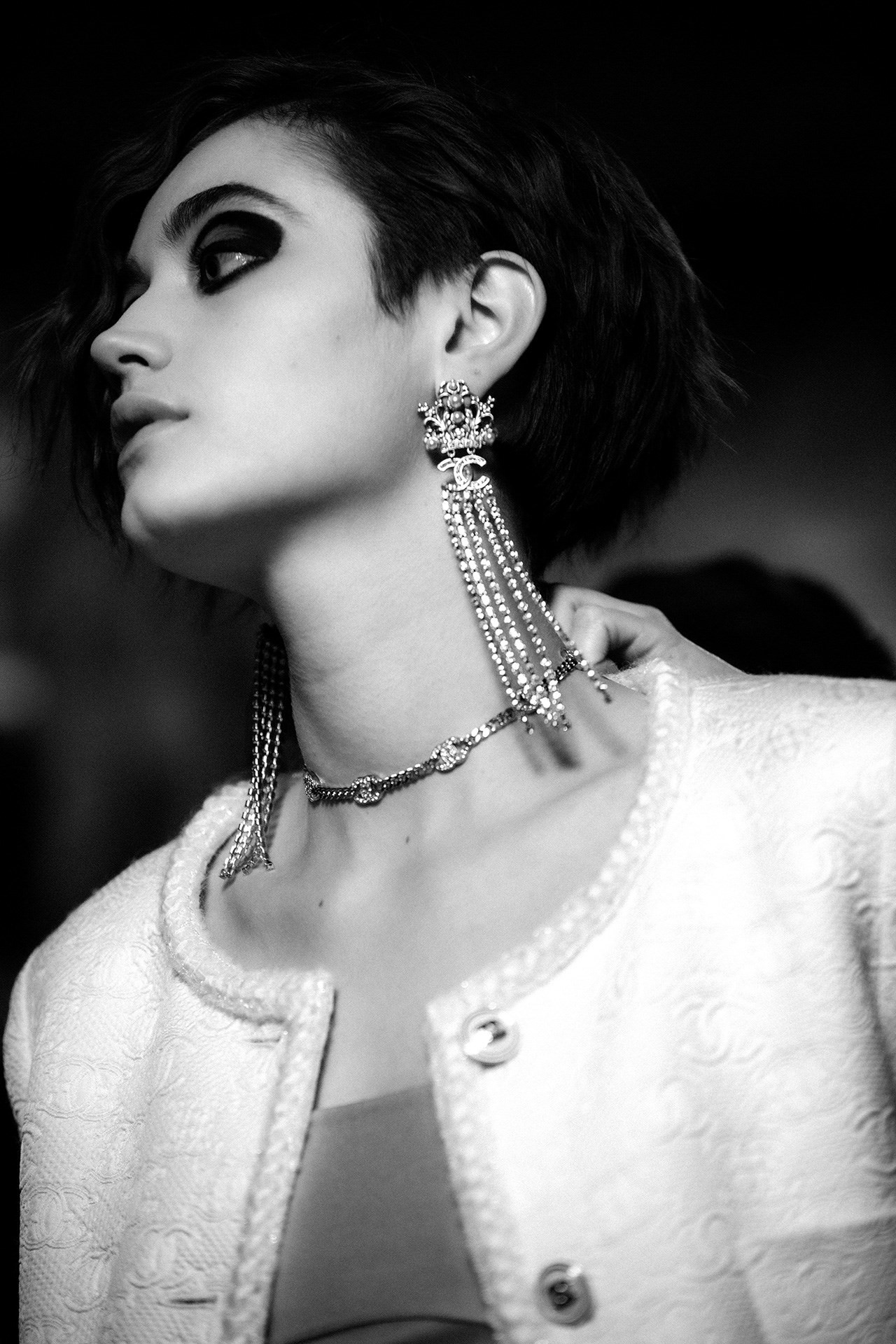

One wonderful thing about Chanel: the multifaceted personality and chequered history of the house’s founder allows connections between pretty much any era, place and inspiration and the maison. Hence a fil of Chanel rouge connecting the 1560s with the 1960s, with the era’s brief miniskirts born from Chanel’s own liberation of the women in the 1920s. Chanel loathed showing knees: wittily nodded to by leggings. And the black-and-white checkerboard floor of the grand gallery, built by Catherine de Medici and spanning the river Cher, inspired chequered sequins and tweeds. Chanel opted to present this collection as a digital show, staged in that grand gallery, with only a single dame in attendance: Kristen Stewart. And, when picked out in seams and latticework, those geometric motifs also resembled the quilted squares of Chanel’s handbags. All roads lead back to Coco.

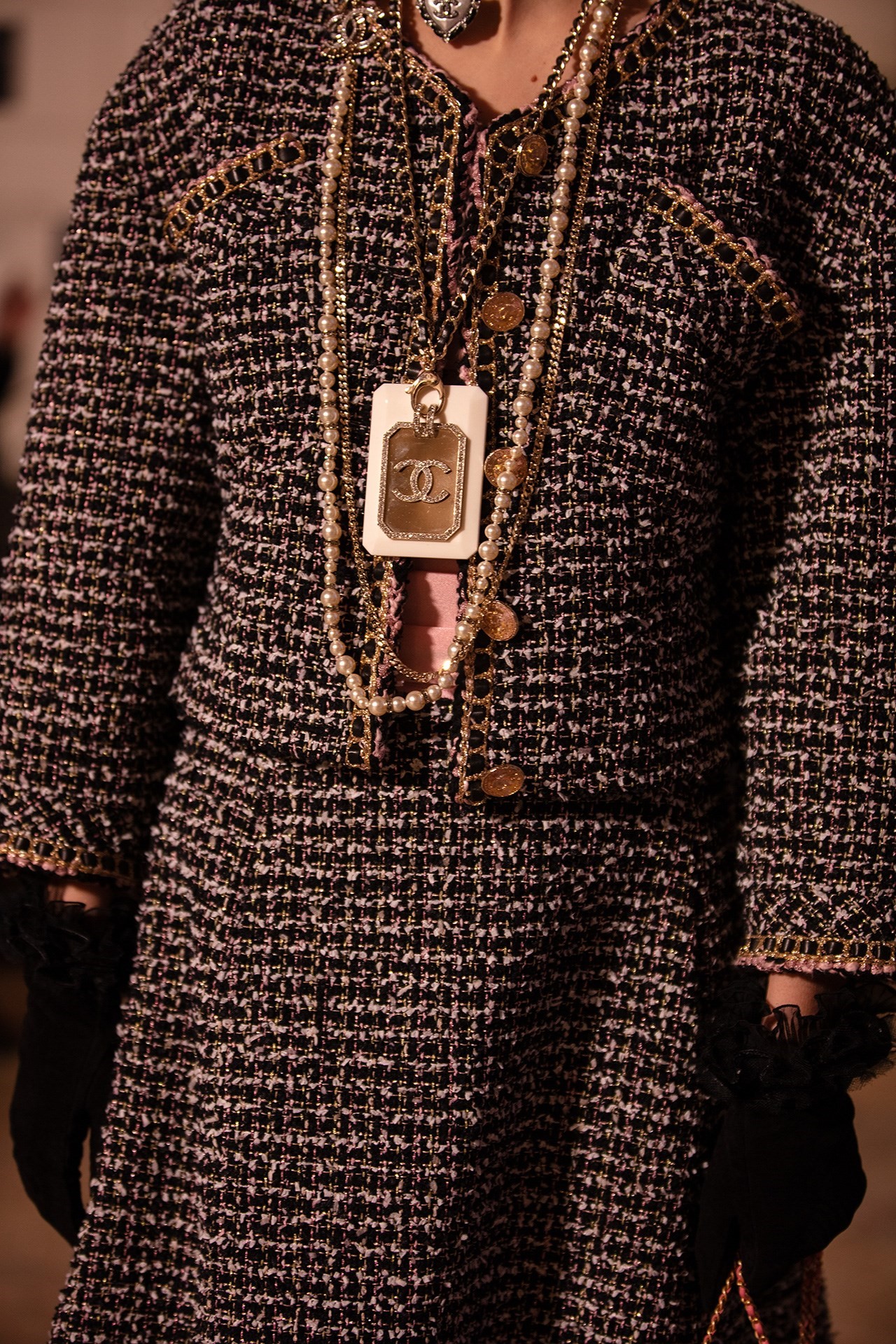

Chanel, of course, famously collided masculine with feminine in her early fashion revolutions. Here, the grander of the clothes of renaissance women were matched with those of their male counterparts: a full-length skirt perhaps teamed with a brief jacket, reminiscent of Chanel’s signature cardigan-soft tailoring, but also of the doublets of the 16th century: a preponderance of studs recalled plate armour. Gently, mind you. That’s the human element Viard mentioned – like the Château, beyond the pomp and decoration of their jewels and, sometimes, their fabrics (she’s synonymous with tweed but adored richly-figured brocades and silks just as much), Chanel’s clothes were engineered to enable women to live in them, inspired by her own experience. Viard has the same mentality: clothes that women can move in easily, clothes for life.

This being not only Chanel, but the Métiers d’Art – the chance for Chanel’s fournisseurs to flex their collective muscle and show off their creativity and craft – the workmanship was superlative. The embroidery maison Lesage created embellishments of flowers, inspired by the château’s gardens (there are two flanking the castle: one planted by de Medici), and trellisworks of ribbon. Goossens recreated renaissance jewellery – when Chanel first began working with that atelier’s namesake founder Robert Goossens, then just 27, in 1954, his designs were inspired by her love of the period’s heavy, ornate gems. They were perfectly offset by her stark clothing. “I also asked the Atelier Montex to make embroideries from the castle in the style of a child’s toy in strass,” Viard relayed, of the finale dresses with waists circled with glittering recreations of the Château’s architecture. “Because I like everything to be mixed up, all the different eras, between the renaissance and romanticism, between rock and something very girly, it is all very Chanel.” Bien sûr.