I remember writing about CANDY – the world’s first transversal style magazine, as its creator and publisher Luis Venegas characterises it – for The Independent newspaper back in 2012, I think. It was when the idea of gender fucking and fluidity was still new to the mainstream and often misunderstood, when trans models made headlines for simply existing at all. Venegas wasn’t tokenistic: he founded CANDY, named after the Warhol superstar Candy Darling, to celebrate. And it is still going strong today.

Venegas has just published a book with Rizzoli celebrating that celebration, photographing spreads from past CANDY issues pockmarked with post-it notes, showing images that resonate with a wider cultural consciousness far more overtly than you would expect from a niche, cultish style title that publishes in strictly limited editions (1,500 per issue). Lady Gaga appeared on the cover of the seventh issue; Hari Nef, who guest edited the tenth, was shot by Nan Goldin for its cover, as the television show she featured in, Transparent, hit the mainstream and amplified issues of trans rights. My personal favourite CANDY cover is that of the fifth issue, featuring model and actress Connie Fleming as First Lady Michelle Obama – “the meeting of two black icons,” said Janet Mock, writer, director, and producer of Pose. It’s powerful, yet also humorous; poignant, but fun. And it’s very much indicative of the unique place CANDY has carved for itself in the cultural landscape.

“Ruth Ansel is a legendary American art director who was responsible for the look of Harper’s Bazaar in the 60s, The New York Times Magazine in the 70s and Vanity Fair when it was revamped in the 80s. That’s a podium hard to beat by any other art director, making Ruth not only a legend, but a very alive and dynamic institution, an inquisitive mind filled with endless curiosity and one of the most inspiring people I’ve ever met. She’s also a dear dear dear friend of mine. I always pay attention to what she says and one day she told me the duty of a good magazine should be ‘to inform, inspire and entertain’. That very simple sharp sentence stuck with me forever and that’s my goal every time I start working on a new issue of my publications.” Those are Luis Venegas’ words. “I always follow that rule and try to feature unexpected subjects, ideas that I’d like to see published in other magazines ... but since no one else seems to be as interested as I am in those, well, I’d better try to make them happen. I hope to be surprised in the process, and above all with the results.” And surprising is the word for Venegas’ own turn, dragged up as Anna Wintour (he does edit CANDY, after all).

I’ve written peripatetically for CANDY across the years – less than I wish, due to the demands of other work and roles getting in my way of doing more – but, for its 12th issue, Luis pinned me down to write about one of my favourite subjects, Fran Lebowitz. Furthermore, he was kind enough to let us reproduce it here, to mark the publication of his Rizzoli CANDY tome.

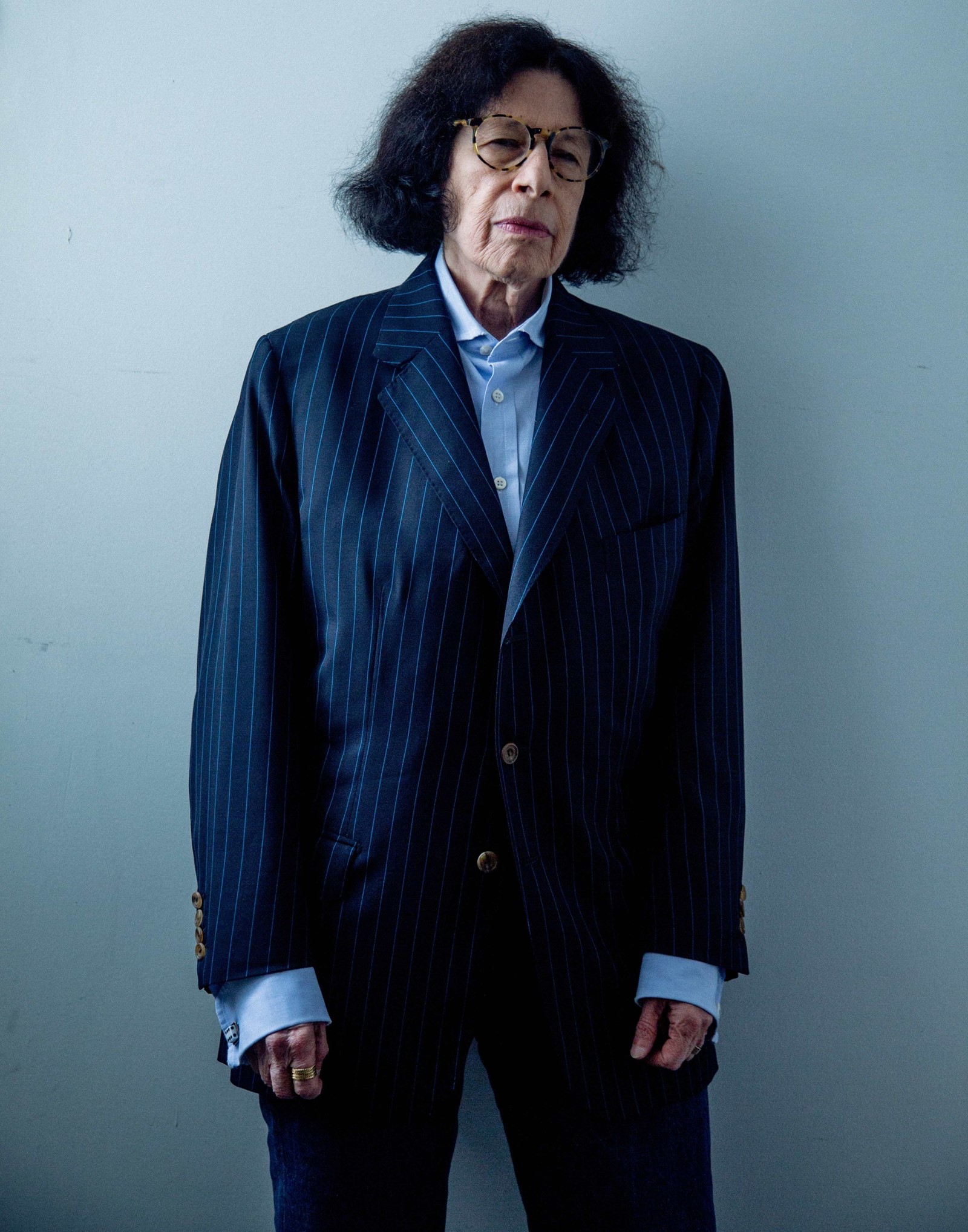

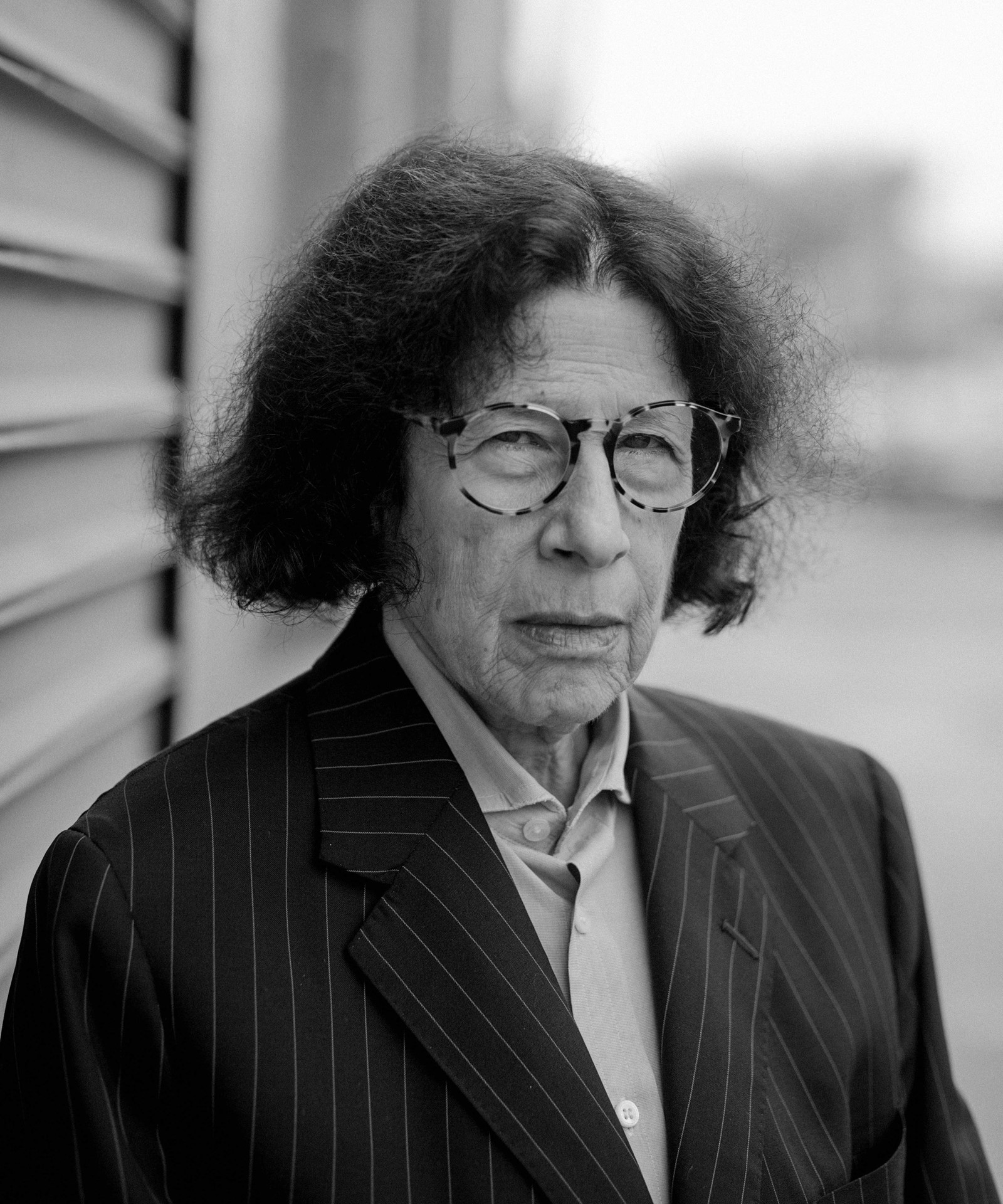

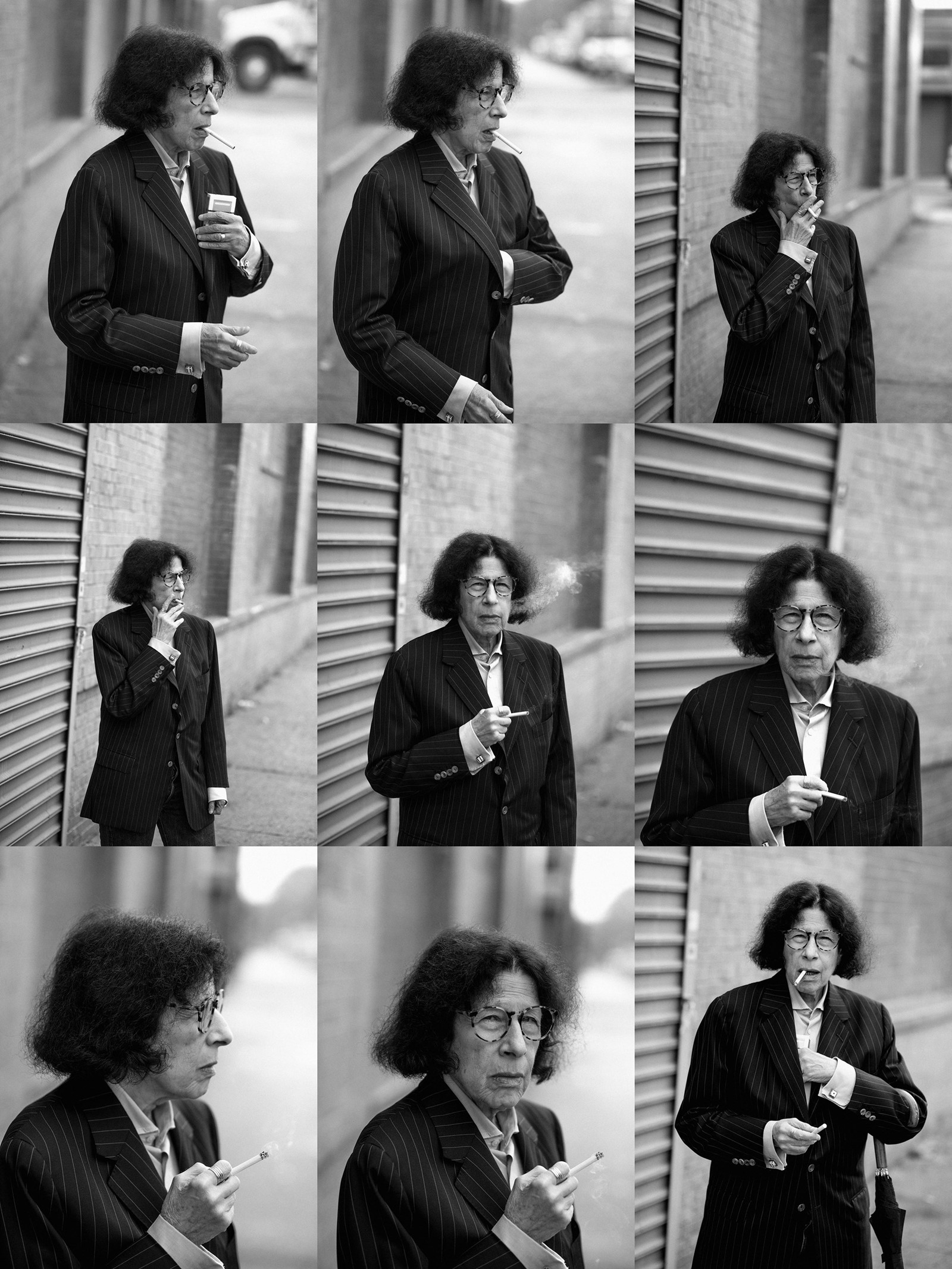

And of course I was excited, intimidated, trepidatious and mildly terrified to interview Lebowitz – as anyone interviewing her should be, if they’re in their right mind. Because Lebowitz is fearsome, and to be feared – razor sharp, erudite, and does not suffer fools gladly. The three hours (yes!) that I interviewed her for felt, very much, like the Martin Scorsese documentary Public Speaking staged as a piece of dinner-theatre – not in the Waverly Inn, but in the studio of Lia Clay Miller, who took the poignant, somewhat enigmatic and extremely beautiful shots that accompanied the piece (a number of previously unpublished ones are included here). It was a magical afternoon, in New York in September, that I’ll never quite get over. Here is the record of it.

I don’t want to say Fran Lebowitz hates a lot of things, because ‘hate’ has become a loaded word in society of late. She hates Donald Trump, implicitly, explicitly, expletively, extensively. We know that for sure. Which perhaps helps to place the rest of her professional griping into context, locking the vast majority of the rest of the world into a complex index of that which merely irks Fran Lebowitz, to varying degrees of incandescence, in an entertaining and erudite manner.

Things Fran Lebowitz tells me she hates: sports. “When I say it, I hate them. It’s not just that I’m not interested, I actually hate them.” She hates Rudolph Giuliani: “When Giuliani became mayor, of course I hated him. I hate him now. I’m never not going to hate him.” She hates hot weather: “I’ve always hated the hot weather. But you know what, we’re not going to run out of water in my lifetime, but, apparently, we’re running out of water. I don’t know how this happened, but I hear on the radio that we’ll be out of water by 2040. And, at first, I think, ‘Oh, my God.’ Then I think, ‘You’ll be dead, what do you care?’” She hates money: “I know this an incredibly bizarre thing to say in this era. I hate everything about money, including money itself. I hate it. I hate money, but I love things, and this is a horrible combination. I love things, I love clothes, I love furniture, I love all these things. It’s OK if you hate money and you hate things, then you’re a Buddhist monk. It’s OK if you love money and you love things, then you make money. But, for me, I’m in this middle ground, this never-never land.”

“And I said, ‘The only person who should ever say a trillion is an astronomer.’ I do not want to hear this in relation to money” – Fran Lebowitz

The collected hates of Fran Lebowitz would make for an entertaining read – their abridged number make for entertaining conversation. What Lebowitz hates generally, fall into a distinct camp: capitalist swinging to right-wing, heteronormative pushing to homophobic, the mundane and the banal. To many, these things aren’t just inoffensive, or normal: they’re aspirational, desired. The American Dream. Maybe that’s not something Lebowitz, the self-described “Willy Loman of literature” is consciously railing against. But she’s puncturing convention, consistently. Challenging the status quo.

“I was at a dinner party, and I heard someone say trillion,” Lebowitz says. She has a doodled scribble of hair, like an edit on a manuscript; her mouth turns up a little at the ends, her eyes turn down. An eyebrow often appears raised. Now 68, her face settled into this architecture in the 1970s, when she first came to prominence, an era that Lebowitz’s lack of digital technology echoes, a time when a ‘trillion’ didn’t exist, particularly not in monetary terms. “I asked this guy sitting next to me, ‘A trillion, what is that, a thousand billion?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ And I said, ‘The only person who should ever say a trillion is an astronomer.’ I do not want to hear this in relation to money.”

Is that sacrilege? Lebowitz is an atheist, so for her, no. But in modern America – where, despite ostensible separation of church and state, the only thing that trumps the cross in terms of influence is the dollar sign – its possibly even worse.

“It’s a thousand billion,” she continues, audibly indignant. “That is ridiculous as an amount of money. It’s ridiculous that people make ten million dollars, let alone a thousand million dollars, which is a billion. No one should have these amounts of money, and if you say this, people go, ‘Oh, why shouldn’t people be able to earn all the money they want?’ And I say, ‘First of all, you don’t earn a billion dollars, you steal it.’ You earn $10 an hour. Earn means work. No one who has a billion dollars worked for it. They stole it, they tricked you out of it, they figured something out, but that is not work, okay? And so this kind of very pure capitalism that we have now, by which I mean capital with no product, like just money, it is something that used to be illegal, and should be illegal.”

“No one should have these amounts of money, and if you say this, people go, ‘Oh, why shouldn’t people be able to earn all the money they want?’ And I say, ‘First of all, you don’t earn a billion dollars, you steal it’” – Fran Lebowitz

So, Fran Lebowitz hates money. Lower down on the list, pure hate mellows into a milder loathing. She loathes technology (she has neither cell phone nor computer), lateness, often writing – not reading, but producing the words herself, which she both fears and loathes – and exercise, which she dislikes more than writing. Below that point is sheer annoyance, the irksome.

I suspect it irks her that we’re in Brooklyn for a photographic shoot – we stare out of the window, on a landscape which, it seems, is alien to us both. I live in London; Fran, she says, doesn’t come here very often. Her apartment in New York is on Seventh Avenue, butting up with the start of the Garment District, and she’s lived in Manhattan since she was a teenager. She came there from Morristown, New Jersey, where she was born and raised, after Frances Ann Lebowitz was expelled from a private girls’ high-school for a well-documented misdemeanour: ‘non-specific surliness’. She achieved her General Educational Development diploma, then came to the city. She drove taxicabs, cleaned apartments, sold magazine advertising space, and wrote. She wrote pornography, but also wrote for Mademoiselle and, most famously, for then-Andy Warhol’s Interview, when she began writing her column I Cover The Waterfront, which she spun into her first two books Metropolitan Life (1978) and Social Studies (1981). They epitomise one of Lebowitz’s strong beliefs, in earning as much money as possible from as little writing. Fran Lebowitz, after all, is a writer. She is one of the great writers of our time.

In person, Lebowitz, is remarkably small. That is only remarkable because Fran Lebowitz, in personality, is larger than life-size. She’s a juggernaut, a titan, terrifying. Her reputation as a latter-day Dorothy Parker was hewn early, and hasn’t been chipped away, despite the erosion of similar monoliths over the same period. Perhaps that is because Lebowitz has – consciously or not – controlled her output, never diluting her worth. I call Metropolitan Life and Social Studies Lebowitz’s first books: bar a slender volume for children titled Mr Chas And Lisa Sue Meet The Pandas (about a pair of Pandas disguised as dogs, in New York City, naturally), they are her only books. Ever since their publication, she has been perpetually half-way through her follow-up, eagerly awaited by readers, and possibly more by her publishing house, Knopf. It’s led people to call Lebowitz a wit, a humourist, an ironist, rather than a writer – because although she is all of those and often in print, its seldom written by herself. Lebowitz herself acknowledges this discrepancy: she’s talked of ‘writer’s blockade’ rather than plain writer’s block: unlike the US versus Cuba, the impasse between Lebowitz and literature, it appears, hasn’t eased. That long-awaited next book was first named Exterior Signs of Wealth; now its working title is, ironically, Progress. Under that moniker, it finally appeared with a 2018 publication date. It has now shifted, to 2019.

Yet a conversation with Lebowitz, speckled with witticisms and sardonic observations and perfectly formed, thought-out sentences framing anecdotes, can often feel like reading her prose. It is just as rich and engaging, easily as informative and definitely as entertaining. Listening to her talk, it often feels like she’s writing in thin air. Her hands occasionally conduct the conversation, whirling a shape that could be a semi-colon, or a sharp apostrophe. They lend punctuation to proceedings.

“I am the world’s best voter ... No, I’m the best voter in the United States. I never don’t vote, no matter how small” – Fran Lebowitz

What Lebowitz has gained a repute for, in words and in person, is being an acerbic commentator on the social and latterly political mores of any given moment. Hers is a voice that others listen to; and when listening to her talk, for an audience of one or one thousand, you’re struck by Lebowitz’s patter and rhythm, her perfect comic timing, the quickness of her mind which, perhaps, is what the challenge is in writing: hands couldn’t possibly keep up with it.

She’s great in front of a crowd. If she ever ran for government, she’d be a shoe-in. Well, probably not. But she’d sure as hell be entertaining. “I am the world’s best voter,” Lebowitz asserts. Then she checks her hyperbole, slightly. “No, I’m the best voter in the United States. I never don’t vote, no matter how small. We had a democratic primary, I think it was, I don’t know, in June, for my congressional district. I was going to be in Madrid, so I got an absentee ballot, no small thing, and it was so complicated, my assistant said, ‘What are you bothering for, getting this? It’s a democratic primary in Chelsea.’ I vote for every single person I can vote for who I never heard of. Maybe the next people will be just as bad, but we don’t know that yet. So, since we already know these people are bad, let’s let the other people come.” Incidentally, money where her mouth is, she voted for Suraj Patel in that democratic primary; she also voted for Cynthia Nixon in her campaign for New York governor.

“This is an incredibly reactionary era,” Lebowitz asserts, connected to both of those choices. “I was unaware of how much people hated Obama for being black, I just didn’t think about it. I mean, I knew that there were people who would hate him for being black, but I didn’t realise it was going to result in Donald Trump. I mean, that is extreme. That is so crazy. That is so just plain stupid, that when Trump was running during the campaign and I started seeing the first of his campaign rallies, I was watching them and someone called and I said, ‘Hey, turn on the news. Look at this. This is a George Wallace rally.’ Now, George Wallace was the governor of Alabama in the 60s, and he ran on a third party ticket, that was a segregationist ticket. And the rallies were racist rallies, that was the point of them, and they were very frankly that, and people that are younger that don’t remember that, I’m sure you could look it up on your device” – Lebowitz gestures to my phone, warily – “and see these rallies, they’re Klan rallies. And I thought, ‘Well, this is going to last two seconds.’ I was really shocked at the level of it, and, also, I knew there were a lot of stupid people in the country, but I didn’t know there were this many, and I didn’t know they were that stupid. Because, truthfully, for those people who support Donald Trump, the ones who go to the rallies, the ones who wear those stupid hats, those people are the most badly affected by his policies. But, apparently, it is so pleasurable to be able to express your racism, that it’s worth it to them.”

Lebowitz’s discontentment with our current era, however, is not coupled with typically reactionary nostalgia. “Nostalgia in itself is a bad thing, I think,” she says. “Personal nostalgia – ‘I remember this tree I used to sit under when I was a child’ – that’s fine, that’s normal. But cultural and political nostalgia is why we’re in this situation. I mean, it is profoundly regressive in a very, very bad way. Not just like, ‘Yeah, I’ve seen these shoes come and go 65 times.’ Shoes, they don’t matter. But ‘Make America Great Again’, what does that mean? Okay, that’s what this means. And what it means again is make it great again for who? The only people things were good for before were straight, white, gentile men, period. They controlled everything, not just in New York, in the world. They controlled every single thing, and most people didn’t even question it. It was like a mountain.”

“But ‘Make America Great Again’, what does that mean? OK, that’s what this means. And what it means again is make it great again for who? The only people things were good for before were straight, white, gentile men, period” – Fran Lebowitz

She pauses. Lebowitz isn’t drinking (meaning water or coffee or similar, as she’s teetotal – she hasn’t drunk or taken drugs since she was 19), or smoking. The gap calls for filling. She does so with more words. “Someone asked me last night, ‘What do you think of the Me Too women? Were you surprised by it?’ I was shocked by it. I was shocked by it. And most shocking things are bad, okay. I was shocked by September 11. But I was shocked by it, because being a woman was almost exactly the same from Eve until, like, four months ago. Did I expect it to change? No, I didn’t. Who would expect it to change? It was incredible to me that this happened, I mean, literally incredible. Noone could have guessed this, noone.” She thumps the table, for emphasis.

You inevitably bump into Fran Lebowitz in New York. Not the woman herself, unless you hang around her apartment building (Lebowitz walks constantly – though she owns and more infrequently drives a pale grey 1979 Checker Marathon). You bump into Fran because she is woven into the fabric of the city, its physical embodiment, if that doesn’t sound tacky and make you think rather more of Carrie Bradshaw and a guided city tour. The graveyard where Lebowitz wants to be buried in is where Rodarte presented their Spring 2019 line, in steady drizzle.

I did once bump into Fran Lebowitz, at a Carolina Herrera show at The Frick. Herrera is a friend of hers; she was also a friend to Geoffrey Beene, who bequeathed her some of his own jackets when he tired of them (the arms were too short for her, Fran says). “I’ve always been interested in clothes,” Lebowitz says. “Which is why I don’t go to fashion week anymore because they’re not about clothes. I always went to Carolina, but, I mean ... it used to be small, okay? First of all, there didn’t used to be very many American designers. All the designers were French or even Italian designers, so if you just said a clothing designer, you meant a French person. Americans, we had the garment business. It wasn’t called the fashion business, it was the garment business, and they sent people to the shows to copy someone else, but once there were a few American designers, I always went. I’m always interested in clothes, plus there are beautiful girls. It was a perfect thing to me. What could be more perfect than a fashion show? I can’t imagine anything more perfect than a fashion show.”

She exhales. “It, as you know, got bigger, and bigger, and bigger. And then straight men started coming to fashion shows, which I just think ... no. No, you should not be allowed at fashion shows.” She smiles, slightly cynically. “They’re not really about clothes, fashion shows, anymore. You used to know what you were looking at. People used to applaud the clothes, because they understood what they were looking at. I went to Paris for the collection, when Saint Laurent was still making clothes, designing, and this was a fantastic thing. Because Saint Laurent was a great designer: not a very good one, a great designer. It was exciting if you cared about clothes, and people would applaud the clothes, because the people at the French shows, which were small, probably knew about the clothes. It’s like there was a connoisseurship to it. The same way that people used to go the New York City ballet knew about ballet. Now, they don’t. They just applaud everything that comes on the stage.” Lebowitz exhales with exasperation.

“It, as you know, got bigger, and bigger, and bigger. And then straight men started coming to fashion shows, which I just think ... no. No, you should not be allowed at fashion shows ... They’re not really about clothes, fashion shows, anymore” – Fran Lebowitz

Lebowitz isn’t just interested in clothes; she cares about them. She is markedly well-dressed. She was, indeed, nominated to the Vanity Fair Best Dressed List (the 68th, in 2007); her style is conscious, careful. Her jackets are Anderson & Sheppard – you can tell by the way the pinstripes in the lapel carefully match up, something which held my attention. Or would have, if there wasn’t Fran Lebowitz talking over it. “I have these jackets, these were all made by Anderson & Sheppard. Anderson & Sheppard is in London, but they come here twice a year. I’ve been having them make clothes for me for so long that, apparently, in London, unbeknownst to me since I’ve never been to their place there in London, there is a dummy. Usually takes three fittings, but it doesn’t always take that anymore, because they have this thing. They’re perfect. They’re incredibly expensive. They’re perfect. And, by the way, I have some jackets from them that are at least 15 years old, maybe more, and they still fit me, and this is ... Your body changes a lot – even if your weight is the same, it doesn’t matter. But they still fit and they still fit. They will always fit as far as I’m concerned. And there are some people who recognise the cut on the clothes, because all those tailors have a different cut. I remember – this is at least 15 years ago – I was at some opening at the Guggenheim, and a man I didn’t know came over to me and said, ‘Is that an Anderson & Sheppard jacket?’ Now, for years they wouldn’t make me clothes, they would not make clothes for women, they would refuse to do it, and a lot of people asked them. Men, who I know had their clothes made there, asked and, no, they wouldn’t do it. ‘No, we only made clothes once for one woman, that was Marlene Dietrich, and that’s it. If you’re not Marlene Dietrich ... ’ which I was not! And then finally, whenever long ago this was, Graydon Carter convinced him to make clothes for me.”

On the surface, Fran Lebowitz shouldn’t be interested in fashion. She skewers pretensions and affectations – both of which fashion thrives on, and always has. But Lebowitz herself has been a keen observer of fashion through her career, weaving it into her narratives and observations in a manner akin to New York chronicler’s past and present, like Wharton or Warhol. She never met the former, obviously; she was introduced to the latter like a knock-knock joke. On the door of Warhol’s Factory was a handwritten notice stating, ‘Knock loudly and announce yourself.’ Lebowitz knocked and announced herself as ‘Valerie Solanas’. Warhol opened the door. It says a lot about a lot – about the time, the place, about Warhol’s sense of humour, about Lebowitz’s chutzpah – that she then became a lead columnist for Warhol’s magazine.

The 70s in New York is an era that you always come back to, with Lebowitz – her columns, her books, are a chronicle of that very specific time in the city’s chronology. “There are certain eras that just stick, okay, in certain places,” Lebowitz says. “Paris in the 20s is always going to be Paris in the 20s, I guess, until Donald Trump blows us up. And the 70s in New York have come back. And would I have guessed that? Absolutely not. But, very frequently, kids stop me in the street and they go, ‘God, I wish I lived New York in the 70s,’ and I think that is just a crazy thing, because even though it was right fun, move on, OK.” Lebowitz’s own opinion switches, between ripping apart New York today, and bemoaning the foibles and problems of the past. Her outlook is not so much anti-nostalgic as fairly indifferent to either then our now, poking at the flaw rather than hurrahing the façade.

Is Fran Lebowitz a ‘gay icon’? As much as I hate that terminology – and as much as Lebowitz runs counter to its implicit implications of camp and theatricality, of Liza and Judy and torch-songs – there’s something about the dry and droll Lebowitz, her caustic humour, that has an immediate affinity with gay men. And she in turn champions homosexuality as a culture and taste-making force. She is obviously counted amongst that herself, although Lebowitz is subtle enough not to state as such. “If you were gay in 1970, there was hardly a place you could live,” she says. “You could stay living in Atlanta, but you’d have to pretend to be straight, OK, so people came to New York just for that. Or they went to San Francisco. But there was a very big difference, because just being gay was not enough in New York, but it was enough in San Francisco. You had a completely different kind of gay world in San Francisco than you had here. Here, you were gay: great, what else? And so the fact that, in the 1970s, you couldn’t be gay outside of New York or San Francisco, it made this incredible culture here, and that’s gone. From a point of view of humanity, that’s good; but from the point of view of culture, it’s very bad. So it depends what you care more about. I care more about the culture than I do about my fellow man, so the culture is very bad, it’s very bland. It’s very nostalgic. It’s very regressive. And a little oppression is not a bad thing, for a culture.”

“This is my main objection to other people – noisiness – and if they’re not making noise, I do not care what they’re doing ... I never have” – Fran Lebowitz

At the same time, Lebowitz’s position on the inside of the inside – in the edgy, downtown Warhol clique, then following the publication of her duo of bestsellers, in a near-unique and prescient position of straddling downtown and Upper East Side, high culture and subculture, at a pivotal moment in the late twentieth century. Not only in terms of culture, but in terms of identity – sexual, political, gender. “I lived in the Village when I was young, and you sometimes saw in the Village, men wearing a skirt or a dress, but you didn’t see it very often,” she states. “You saw it in bars and things like that. People I knew, like Candy Darling, she’d just walk around, but Candy was very frequently thought to be a woman. That was less because she looked really like a woman than it would not occur to someone that a man would look like that. There used to be a restaurant up town called Brasserie; we used to go out there sometimes, because it was open all night, it was kind of a fancy restaurant, and I was in there with her one night, and a man, like a very straight guy in a suit sent a drink to the table. He was trying to pick her up, and I said, ‘If he knew who you were, you know, he would go insane.’” Lebowitz shrugs. “She was always very pleased when that happened, but it’s not ... I mean, she did look quite a bit like a woman, but the ability to really look like a woman did not exist then. It just would not have occurred to them.”

Lebowitz is, expectedly, permissive on such matters. “If someone tells me, ‘I was born a boy, but I feel like I’m a girl,’ I believe them. How would I know how they feel? If someone tells me they have a headache, I don’t say, ‘No, you don’t,’ so I believe them. But people are very preoccupied with this. It’s very upsetting to people, because it’s the most profound thing about someone, I mean, biologically. It’s the most profound biological thing about someone. Mainly, when people are upset about other people to this huge extent, it’s because they’re upset about themselves. It doesn’t upset me. I don’t really care what other people do, just don’t make noise. This is my main objection to other people – noisiness – and if they’re not making noise, I do not care what they’re doing.” Fran Lebowitz smiles, wry. “I never have.”

The Candy Book of Transversal Creativity: The Best of Candy Magazine, Allegedly, published by Rizzoli, is out now.