The style of the house of Chanel seems easy to sum up: neat suits, little black dresses, quilted bags, two-tone shoes. Oh wait, camellias and pearls too. And big enamelled cuffs with Maltese crosses. And beige, and tweed, and brocade, and boater hats, and fur coats with the fur reversed, worn on the inside, an example of what the New Yorker – way back when in 1931 – called the “genre pauvre”. So Chanel style is way more multi-faceted and multifarious than you may initially believe, not least in the way it was endlessly revived and revised over the past four decades by Karl Lagerfeld.

For the book Chanel: The Impossible Collection, I was asked by Assouline to act as a kind of ‘curator’ for a book proposed as an ‘exhibition in print’. The idea was to drill down to 100 items that best represent the house of Chanel. Not an exhaustive list, but a kind of distillation of what Chanel means – then, now, always. Impossible is an apt word, especially when Chanel (both house, and the woman herself) is constantly fluctuating, evolving and changing. And yet the aforementioned constants are there – they gradually emerge through the 20s and 30s, a few sprouting in the early 50s, and are then relentlessly refined, tweaked and tailored to perfection. The suit is a great example, Gabrielle Chanel gradually adding and subtracting elements, trying to get the recipe perfect. She wore her suits herself, constantly, so through a process of trial and error she tried to make them perfect – to borrow a phrase her fellow countryman Le Corbusier used to describe his similarly practical, minimally engineered houses, she saw her designs as “a machine for living in”. Clothes, she said, must be logical – a phrase which could describe Le Corbusier’s building too.

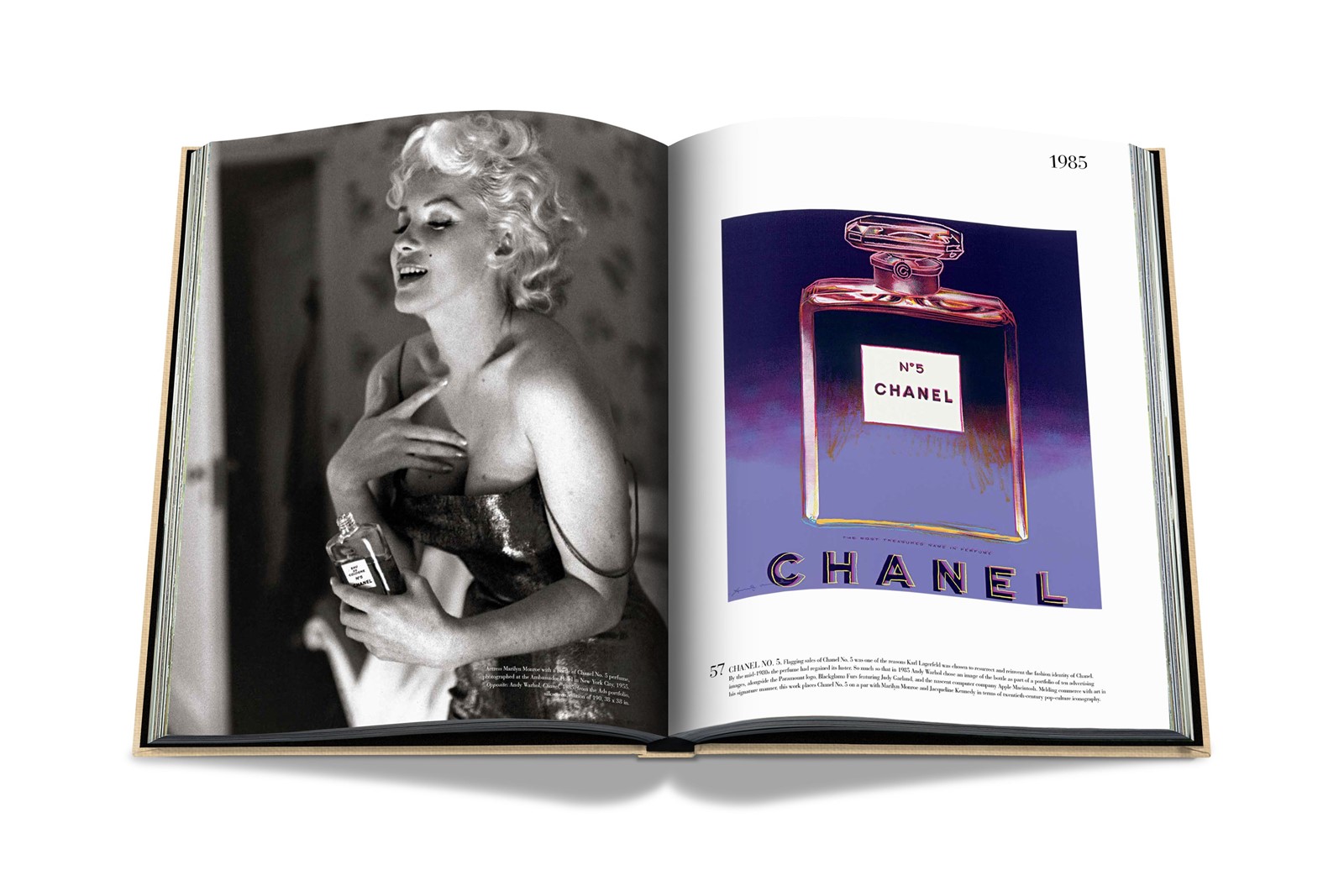

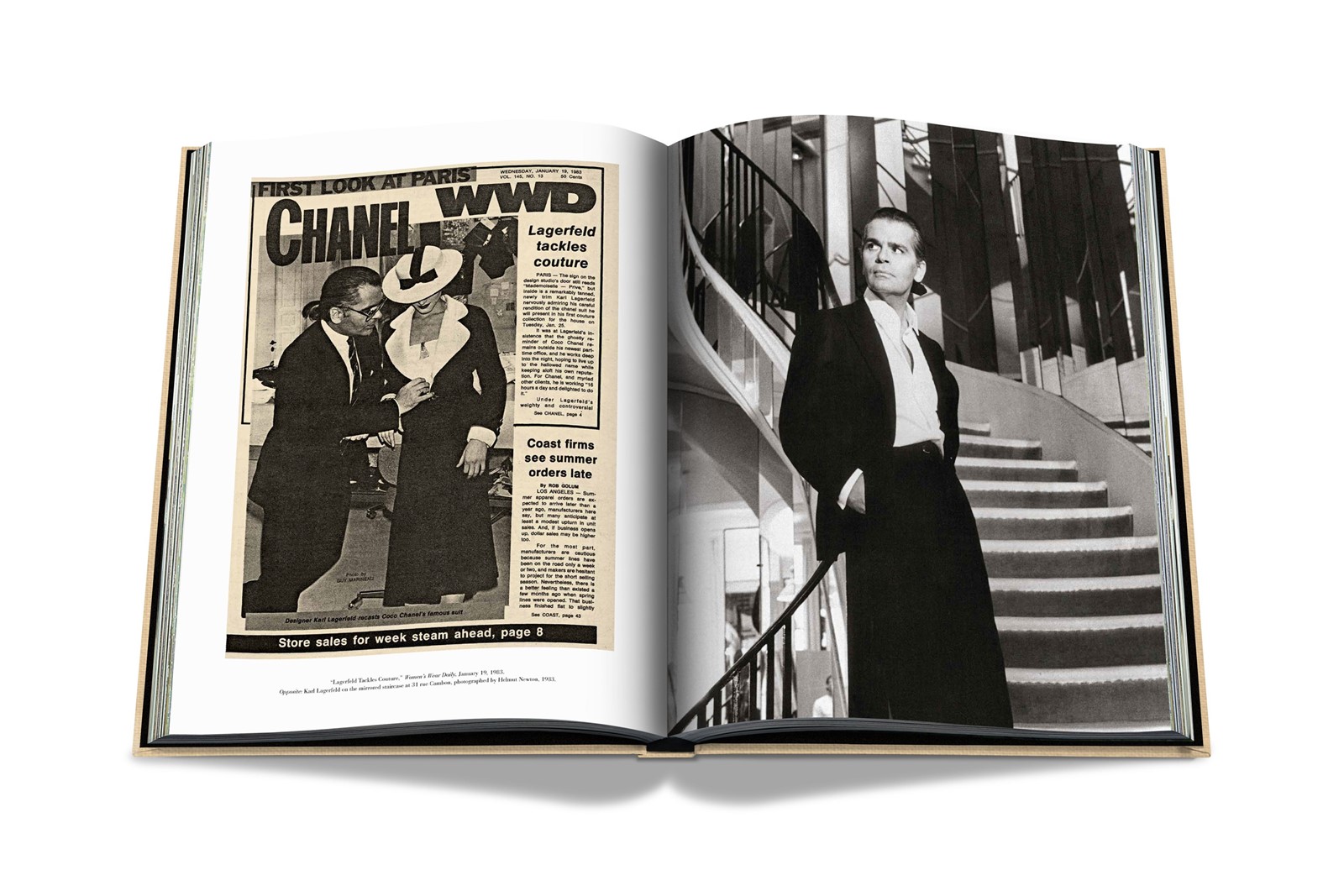

Karl Lagerfeld’s designs were supremely illogical: he loved parody and inversion, and held no truck with the popular idea of Chanel as sacred and untouchable, worthy of homage, such as those reverently and repeatedly paid to her style by Yves Saint Laurent. His Spring/Summer 1990 Haute Couture collection is just one example – devised as a series of homages’ to figures such as Maria Callas, Christian Bérard and Marilyn Monroe, also included one to Gabrielle Chanel. “People before had tried to revive Chanel with respect,” said Alain Wertheimer, one of the two owners of the house. “But you can’t stand still, in fashion or in business.” Hence, they hired Lagerfeld, who reinterpreted Chanel tirelessly, making her style part of fashion once again. If Gabrielle Chanel established the style that bears her name, Karl Lagerfeld kept it alive. “There are lots of things people think are native to the house which are born since I’m here,” he told me in 2017. “I’m pretentious enough to say that we invent something for today, that people can identify as Chanel, even if she never did it.” And, in devising this selection of 100 pieces, it was important to ensure both Mademoiselle Chanel and Lagerfeld were equally represented, as they are equally important to the identity of Chanel today.

Having whittled down Chanel to an impossible 100 pieces here are, perhaps, the ten most important ideas that comprise the identity of Chanel today – the ten Chanel commandments.

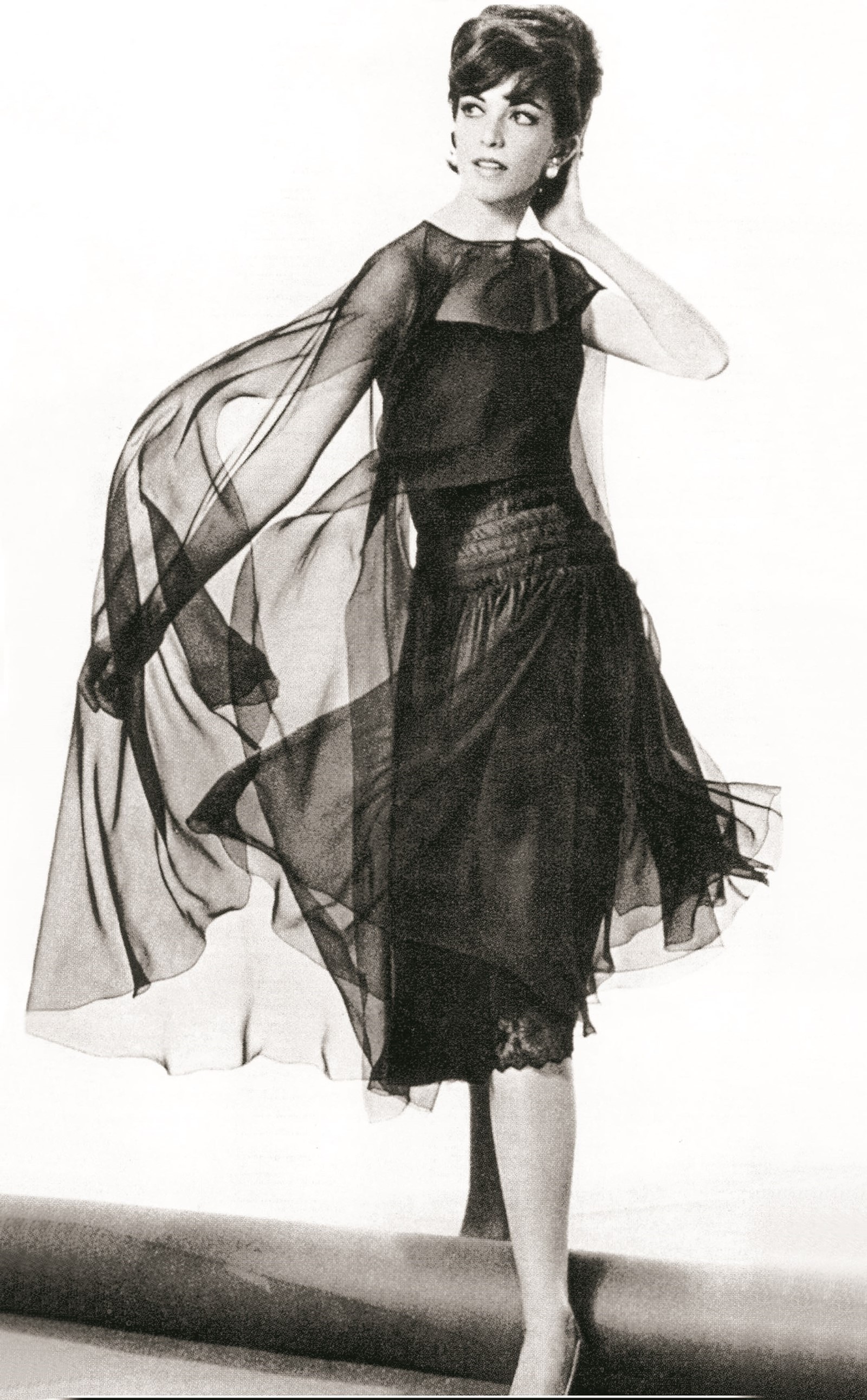

The Little Black Dress

Chanel’s little black dress was ‘invented’ in 1926, when American Vogue declared a model from her winter collection as “the frock that all the world will wear”. A colour favoured by Gabrielle Chanel through her entire life – often combined with white, reminiscent of maid’s uniforms but also the habits of the nuns in the orphanage she grew up in – it was executed almost always with resolute, almost ascetic simplicity, for night and day. This example, from 1961, combines its monastic austerity with the erotic frisson of lingerie, a lesser-known Chanel signature.

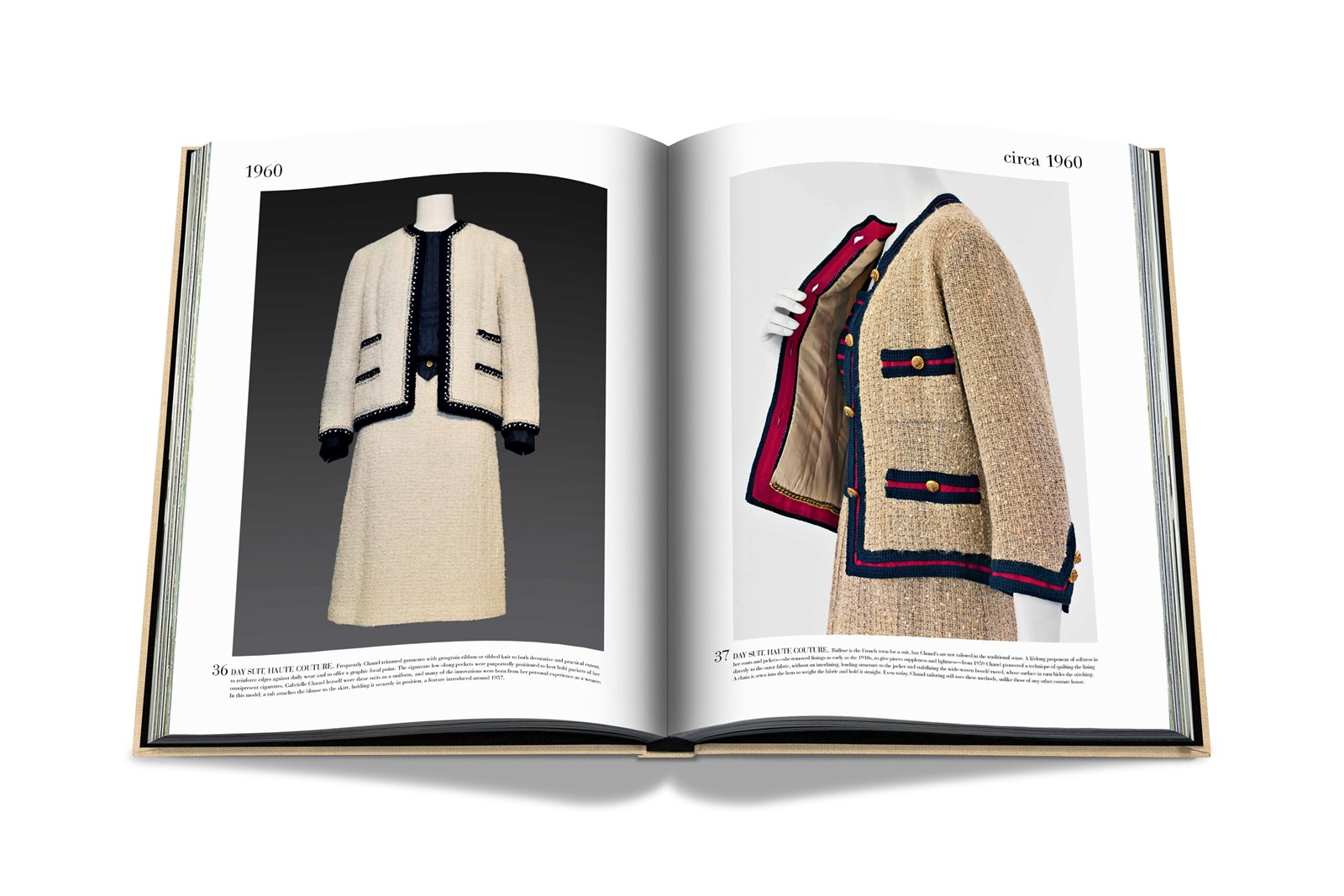

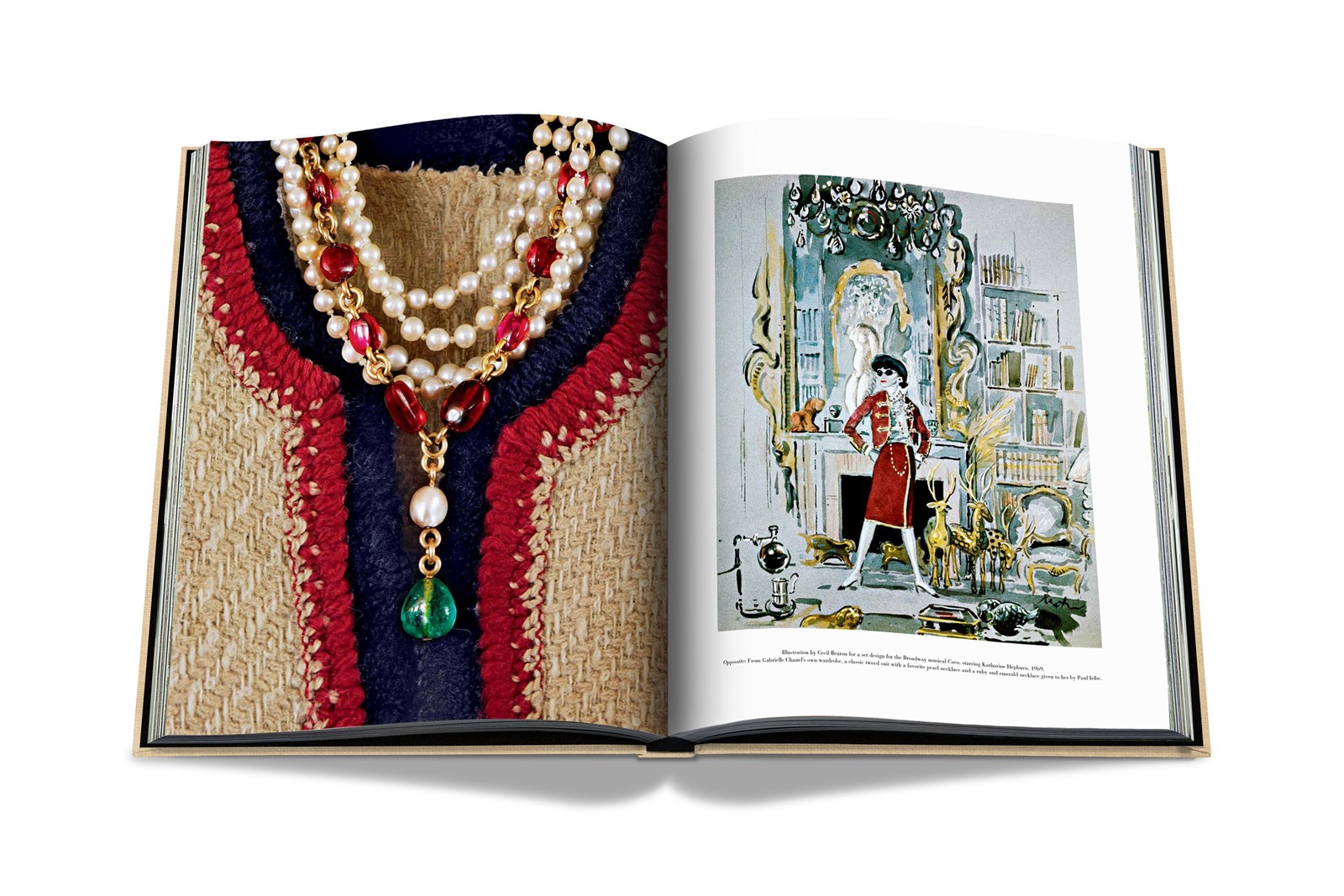

The Chanel Suit

Having closed her couture salons after the outbreak of war in 1939, Chanel returned to fashion on February 5, 1954 – instigated, commercially, by a decline in perfume sales, and aesthetically by her own instinct to offer a counterpart to the “upholstered” post-war clothes of male couturiers like Dior. Chanel’s debut received a muted reception from the press – yet it would become, arguably, the most influential style of the latter half of the 20th century. One innovation, proposed in the first outfit of this second incarnation of Chanel, was her suit. She had proposed similar styles from the very start of her career, jersey dress and jacket combinations she called “sporting ensembles”, and they appeared throughout the 20s and 30s. But in the 50s, she established a formula for her suits, tweaked and changed, gradually evolved through Chanel’s personal experience – she dressed in her suit night and day. Its key elements: a cardigan jacket, so softly tailored its hem had to be weighted with a gilt chain; an easy knee-length skirt; a nubby tweed fabric, edged emphasised and reinforced with braid trims; and every button with a buttonhole, or not at all.

The 2.55 handbag

An essential part of the ‘uniform’ Chanel began to create for her women – and, most of all, herself – in the 1950s was the 2.55 bag. With a typically Chanel numerical nomenclature, indicating the months and year in which is was first shown (February 1955, her third collection since her comeback), the 2.55 has its roots in the 20s and 30s, when Chanel began to create shoulder bags after finding the period’s ‘clutch’ styles inconvenient and impractical. Taking inspiration from soldier’s knapsacks, toted on the shoulder and leaving the hands free to, as Chanel herself said, “get on with things”, the 2.55 was an instant success. The model was executed in quilting, reminiscent of Chanel’s suits, and had adjustable chain straps. The interior was frequently burgundy, a colour many said was chosen because of the uniforms of the Aubazine orphanage where Chanel was raised. Practically, it also made it easier for a woman to find her belongings inside.

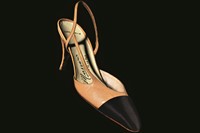

The two-tone shoe

Created in 1958 with couture shoemaker Raymond Massaro (whose atelier is now part of the Paraffection subsidiary owned by Chanel), the two-tone shoe formed the last element of the newly emerged Chanel ‘look’. The style was designed by Chanel to both elongate the leg and shorten the foot, lettering a woman’s silhouette; balanced on a practical low heel, and with the first use of elastic in a shoe strap, it again permitted maximum ease and freedom of movement. It also featured her two favourite colours – beige, softer than white, was favoured by Chanel because it reminded her of soil, another link to a childhood whose facts she assiduously and fastidiously rewrote but which nonetheless marked her aesthetic.

Chanel No. 5

The perfume that made Chanel’s fortune and secured her future, No. 5 was thus named because it was the fifth formula Chanel was presented with, five also being a lucky number. A soapy-smelling aldehyde, its scent was something bold and new in 1921. Its bottle was also bold, based on medicine bottles, whiskey decanters and men’s toiletries, rather than the complex cut-glass flaçons of traditional perfume. Its revolutionary design changed the aesthetics of perfume – designs following it ape its clarity of glass and rectilinear, clean shape, while one of the originals is now included in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Museum. The fragrance inside is, arguably, the most famous one ever created.

Camellias

Chanel used multiple flowers during her career – her dress of the 1930s, which seem uncharacteristically romantic, ruffled and feminine to eyes accustomed to the later ‘look’ of Chanel’s comeback years, often features corsages of fabric flowers as decoration. But the camellia would become the flower most associated with the fashion house – its meaning, tied up with female sexuality as explored in Alexandre Dumas fils’ novel La Dame aux Camélias, underscored the libertine stream behind many of Chanel’s innovations. When reviving Chanel in the 1980s, Karl Lagerfeld seized on the camellia as a house code to be explored – here, the flowers used to trim the sleeve of a lace gown. Polite, compared to the 1993 collection where camellias were perched on the pubis of Chanel-branded Y-fronts.

Fake jewels

Gabrielle Chanel was revolutionary in her approach to jewellery. Previous seen as gauche and cheap, Chanel invented the idea of costume jewellery as fashionable so that, as she put it, “women can wear fortunes that cost nothing”. Chanel’s own collection of precious jewellery, given to her by lovers including the Russian Grand Duke Dmitri and the Duke of Westminster, was the inspiration for her fakes: ropes of imitation pearls and, later, Byzantine-inspired pieces with poured glass gems created by the atelier of Gripoix in the 1930s, and later by the young jeweller Robert Goossens. Chanel herself wore the jewellery as she wanted her clients to: jangling together precious gemstones with costume glass, reality with fantasies. In January 1983, when Karl Lagerfeld presented his first haute couture collection under the Chanel label, he paid homage to this style with a postmodern twist: Lagerfeld turned to the house of Lesage to create embroideries of Chanel jewellery on a long black dress: fake jewels, made fake again. It proved emblematic of the humour and panache with which Lagerfeld would ceaselessly reinvent Chanel’s style for 36 years.

The Verdura Cuff

Many key elements of Chanel style are born directly from the personal tastes – and wardrobe – of Gabrielle Chanel. In 1930, she commissioned the aristocratic jeweller Duke Fulco di Verdura to create enamelled cuffs, decorated with symmetrical geometric designs of mismatching gemstones. A hybrid of precious jewels and the “junk” costume jewellery she had made fashionable, the first cuffs were made with jewels from Chanel’s own pieces, which she asked Verdura to redesign. They were enamelled in white, while their Maltese cross design was a motif taken from the duke’s childhood in Sicily – not far from the Amalfi coast and Malta. They also visited museums and examined Renaissance pieces, which influenced her jewellery designs fundamentally from this period on.

Paradox

An abstract one, but has there ever been a style more paradoxical, more unorthodox than Chanel’s? Like Vivienne Westwood – perhaps the designer who, oddly, is closest to her in intent – Gabrielle Chanel railed against all conventions and received ideas, perpetually challenging the status quo. In the 1910s, when women had been richly dressed in fine fabrics, she proposed jersey underwear fabrics for simple, unadorned dresses; in the 1920s, a Golden Age of glittering wealth, she “utilised the ditch-digger’s scarf, made chic the white collars and cuffs of the waitress, and put queens into mechanics’ tunics,” as the New Yorker said in a 1931 profile. And then, during the depression of the 1930s, Chanel unleashed her hitherto hidden extravagance. This lesser-known period of Chanel was Karl Lagerfeld’s favourite, when she explored rich laces, sequin embroideries, ruffled organza evening dresses and velvet theatre suits. She also created coats of extravagant brocades bordered with sables, and in 1932 executed a collection of star-shaped diamond and platinum jewellery of untold expense. When Lagerfeld inherited her mantle, he was equally unorthodox, layering on decoration, ripping apart the Chanel style and turning her timeless suit into the ultimate timely emblem of fashion. “If I would be pretentious, I would say that I reinvent tradition,” Lagerfeld told me in 2017. “My job is to make-believe. There is no other way for a fashion house to survive.”

Reinvention

Maybe the ultimate code of Chanel is reinvention – ceaselessly, and endlessly. Gabrielle Chanel began by reinventing herself, hiding her birthdate, the orphanage she was raised in, and reshaping her family tree, mercilessly rearranging facts to suit the story she wished to tell. In 1953, when coaxed back to reopen her haute couture house, she reinvented herself again – she became the patrician couturiere, proposing styles that echoed the 1920s but were reengineered for the times and contained a new selection of greatest hits: her slipstream billowing chiffon dresses and flared cocktail gowns, her tidy short evening suits in figured brocades. And then, following her death and a static hiatus of 12 years, Chanel was reinvented again by Karl Lagerfeld – with a healthy dose of disrespect. Lagerfeld inverted Chanel’s maxims, challenged her legacy, remixing her greatest hits like a fashion DJ and finding a new currency in styles that had, after three decades of reiteration, become stale, staid, even dowdy. Lagerfeld gave it a shock-treatment. Today, Chanel is being reinvented again – Lagerfeld’s successor, Virginie Viard, is lightening up layers, pulling out stuffing, toning down excess and referencing one of Chanel’s many heydays in the 1960s, when the house was dressing Nouvelle Vague French actresses, subversively, in subtly bourgeoise style. “A woman with nonchalant elegance and a fluid and free silhouette,” was Viard’s inspiration for her first Chanel haute couture collection. Which sounds both very today, and very Chanel.