In 1991, the atelier of the designer Azzedine Alaïa moved from the Rue de Bellechasse on the Left Bank to the heart of the Marais into an enormous complex that’s still home to the nucleus of the Maison Alaïa today. Alaïa had bought the building in 1987 and began showing his collections there in 1989 when he first staged a show in the vast glass-roofed, iron-columned atrium off the rue de la Verrerie: on that first showing, rain dripped through age-worn cracks in the 19th-century cantilevered ceiling onto models and audience alike.

But in 1991, when Alaïa himself moved both his work and life into the building, he made an unexpected discovery. Researching the building’s history, he discovered it was once home to Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, an 18th-century marquise more commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, a legendary French figure whose life story combines art and fashion, style and politics – of both the socioeconomic and sexual kind.

Madame de Pompadour was a figure that understandably appealed to Alaïa: born into middling beginnings, through her femininity she propelled herself to astronomical success against the opposition of a patriarchal society, ascending to the very highest ranks until her untimely death aged just 42 in 1764. She became mistress to Louis XV in 1745, but that was almost incidental to her larger role as a cultural tour de force, affecting the taste of an entire generation. The style we call Rococo was largely born from Pompadour’s personal affections; we still name an upswept hairstyle derived from the high-piled coiffures characteristic of the period after her. And her artistic patronage shaped architecture and interiors generally, alongside specifically establishing Sèvres porcelain and supporting the creators of the Encyclopédie. Of François Boucher, an artist whose most significant and memorable works include several portraits of his patroness Pompadour, the French 19th-century historians the Goncourt brothers wrote: “Boucher is one of those men who represent the taste of a century, who express, personify and embody it.” That is doubly true of the woman he painted.

The Show

Azzedine Alaïa took Pompadour as the inspiration for his Spring/Summer 1992 show, translating style of the 18th century to that of the late 20th without a hint of historicism. Forget ruffled cuffs and eschelles of taffeta bows: redingotes became fitted jackets over swinging pleated skirts and shirts, nodding to the masculine equestrian styles of the period. Fact: riding habits and corsets were the only 18th-century garments that could be made by men for women – the rest were created by the marchandes des modes, female dressmakers responsible for the creation and decoration of women’s dresses. The most famous of these was Rose Bertin, who emerged a generation after Pompadour to dress Marie Antoinette. Dubbed her ‘Minister of Fashion’, Bertin’s dictatorial role is seen a precursor to the imperious haute couturiers of a century later – but Alaïa’s focus on corsetry and tailoring for his neo-Pompadours was entirely in keeping with her power base of the 1750s.

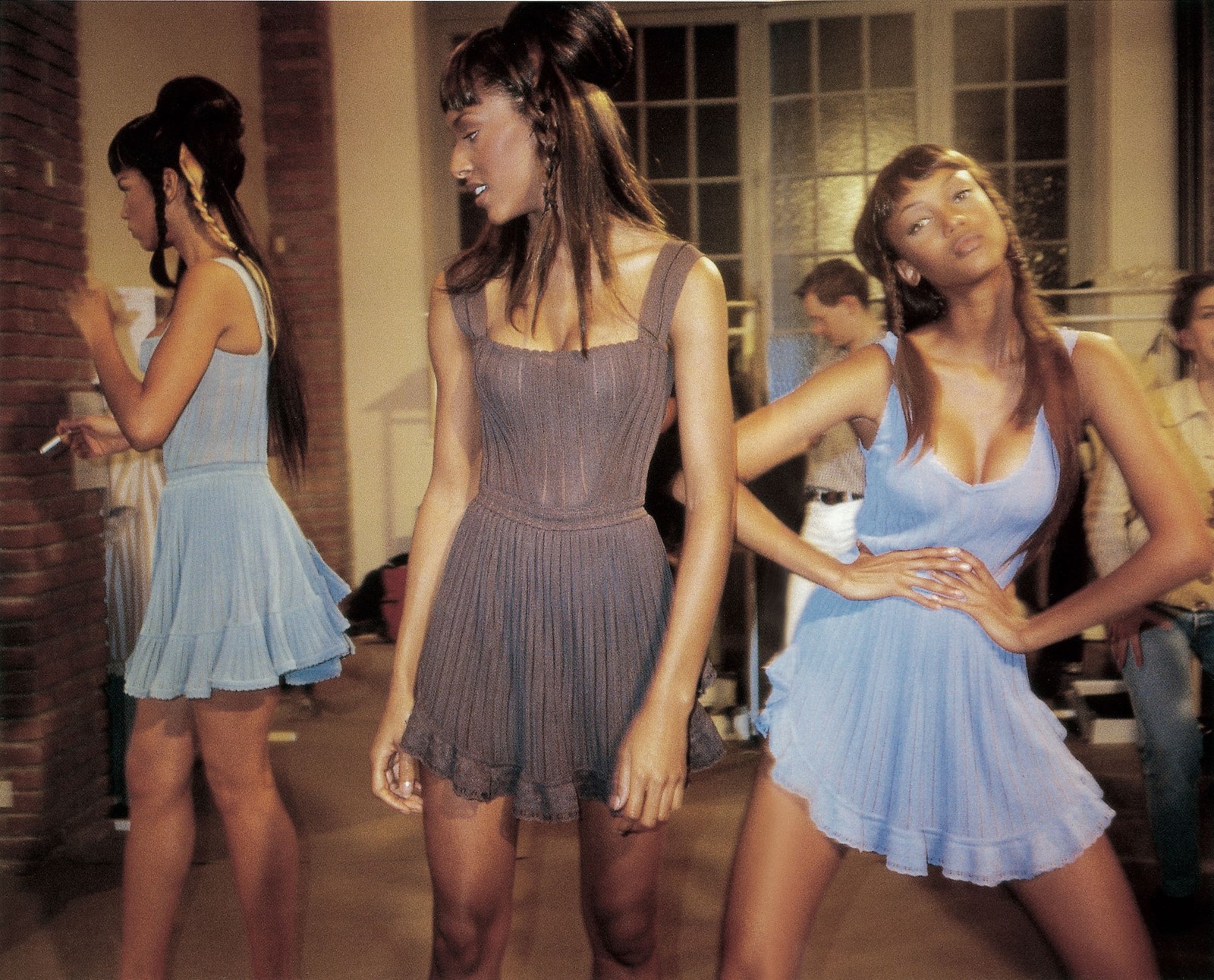

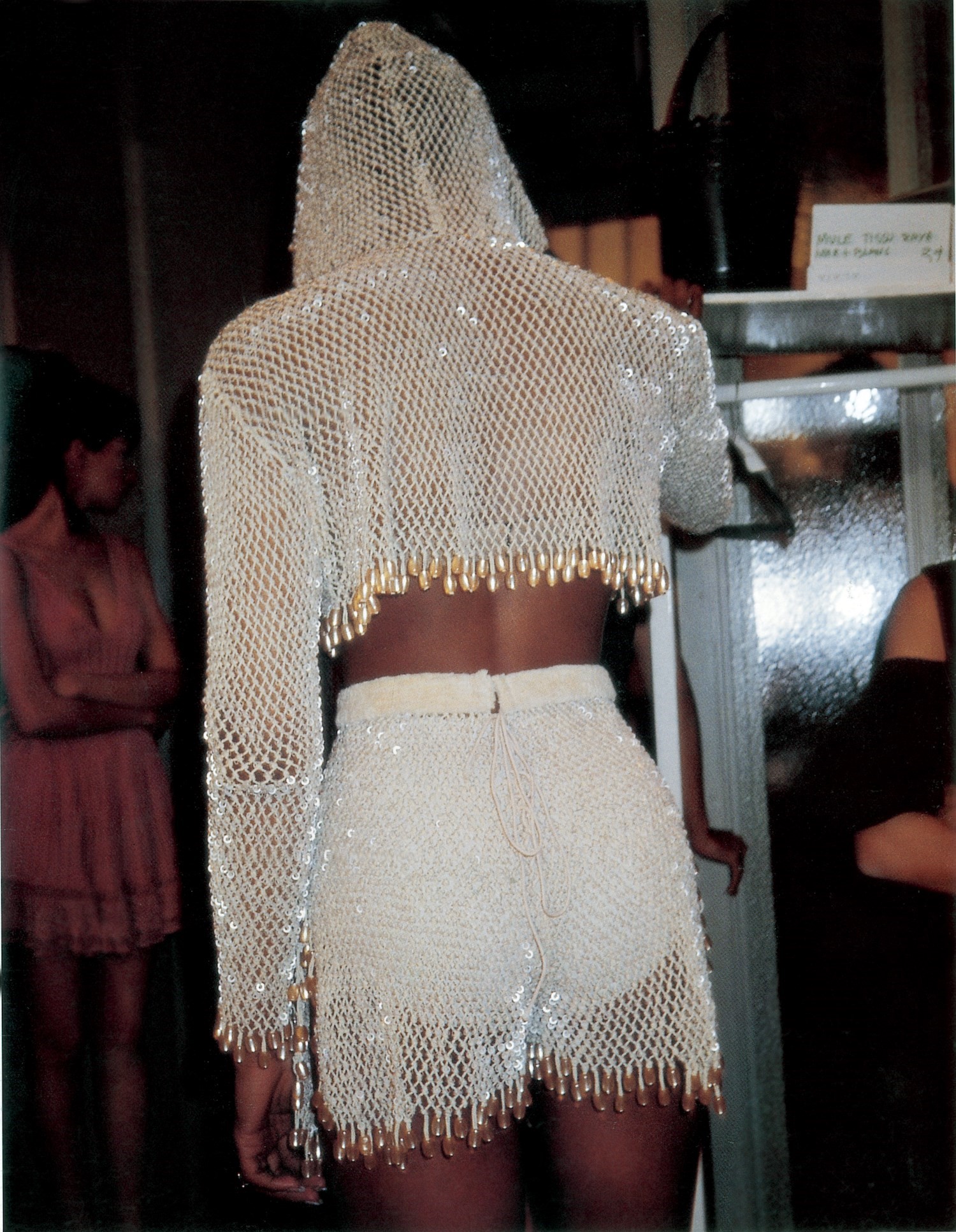

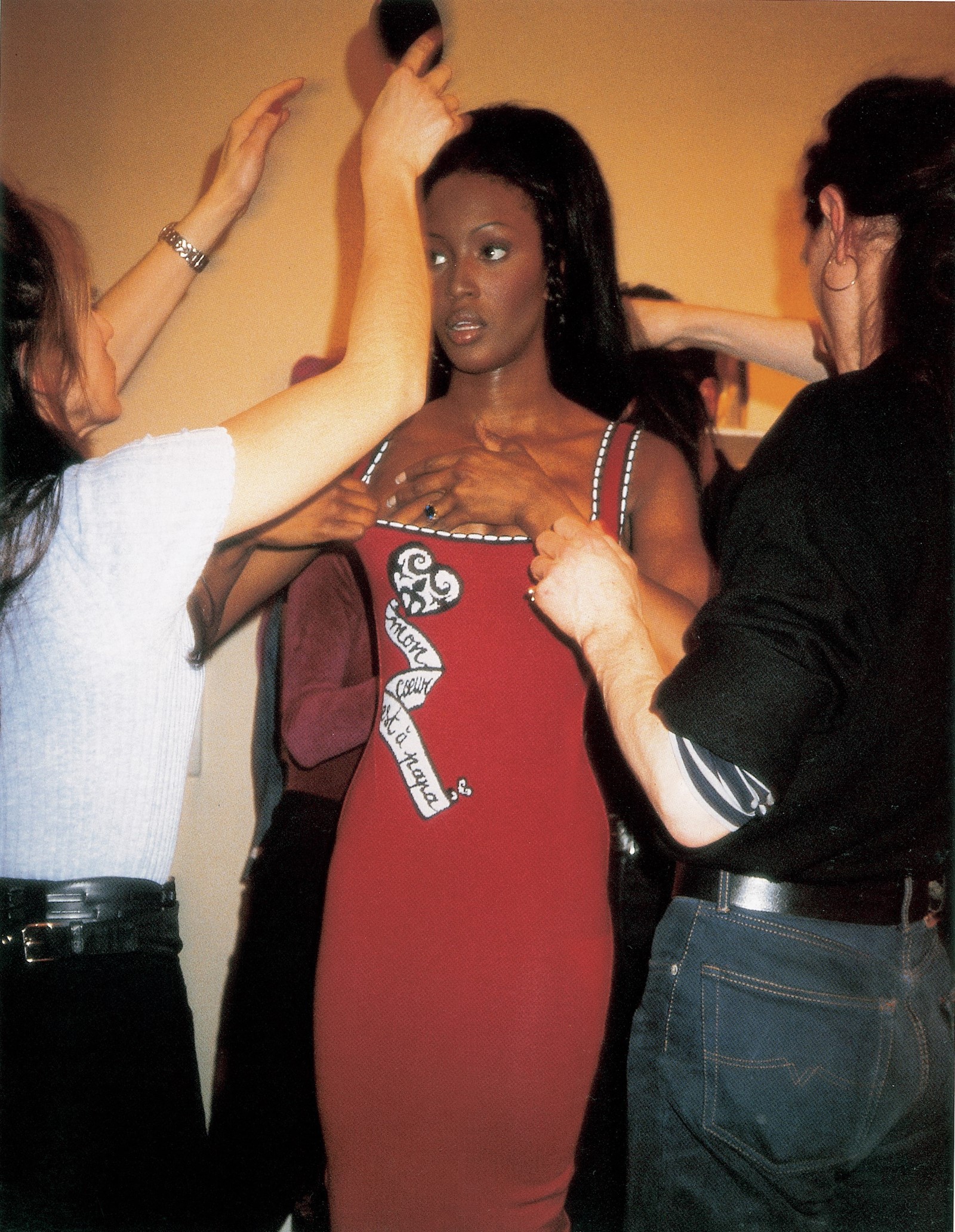

The silhouette sketched out the low-cut bodices and swelling panniers of the period, but through Alaïa’s fabrics: his already-signature leather, a broderie anglaise borrowed from Baroque underwear which would become a trademark, and his body-clinging knits. These were dubbed ‘Relax’ by Alaïa, a notion evoked not just by the easy fit of the stretch fibres but the psychological effect of the fabric itself. Bear with me: devised by Alaïa in collaboration with Florentine textile mill Lineapiù, German textile firm BASF and NASA, Relax contains a carbon yarn developed for use in astronaut’s uniforms. It became wearable when mixed with rayon, or cotton and wool, and acts to screen the body against pollutions and potentially harmful effects of electromagnetic microwave emissions. Alaïa wove it into brief skirts, bustiers and leggings, like underwear as outerwear, except Alaïa had already proposed them as such several years ago, so now they were no longer considered shocking. What did shock in this show were Alaïa dresses with intarsia Rococo swirls across the pubis like wrought ironwork, or Louis Quinze merkins. Alaïa always had a sense of humour – often discussed in reference to his person, seldom appreciated in his clothes. The pin-up outline of Alaïa’s lifted buttocks and breasts, and the Monroe-esque wriggle his taut skirts necessitated, were never accidental. Both he and the women he dressed were in on the joke.

The People

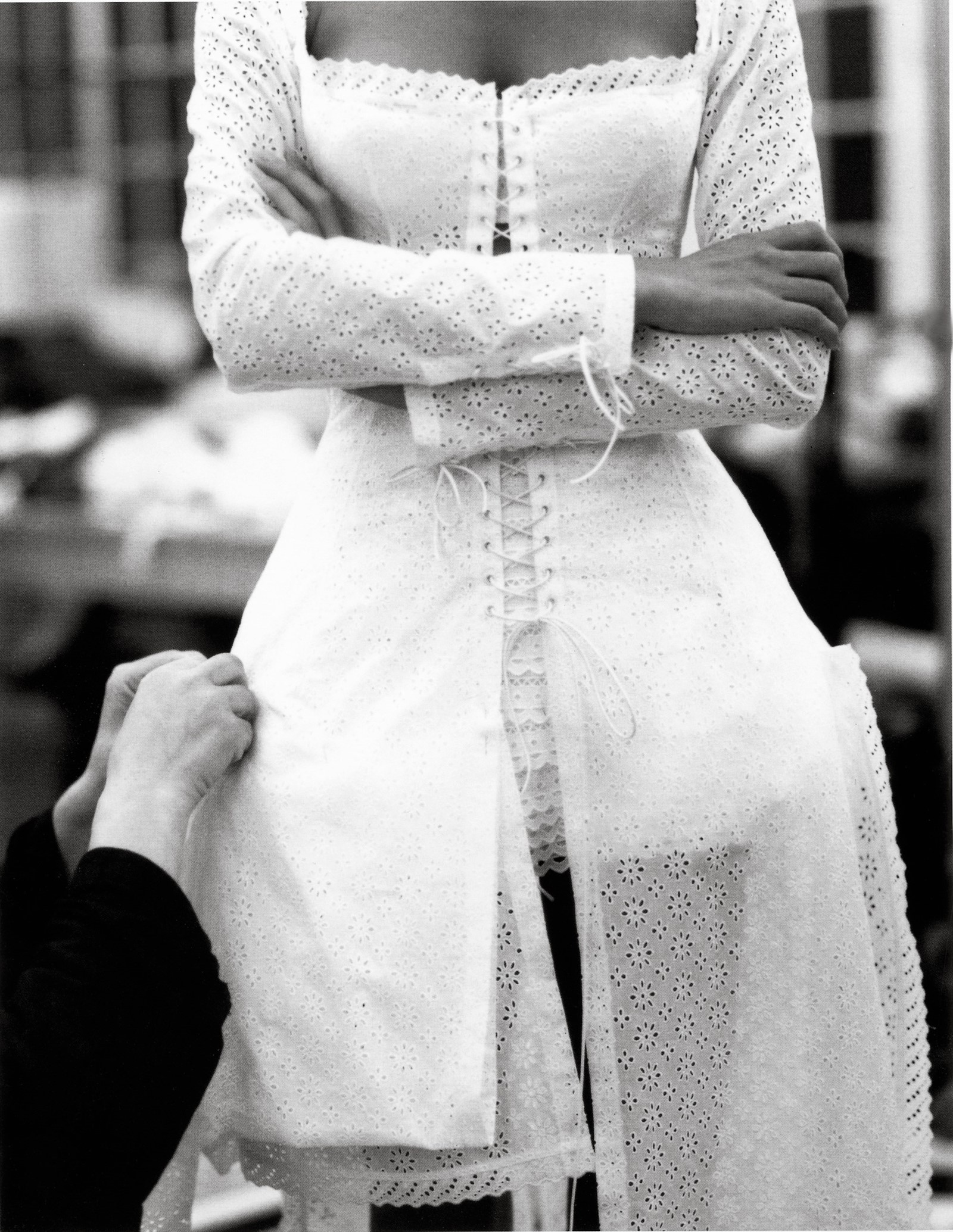

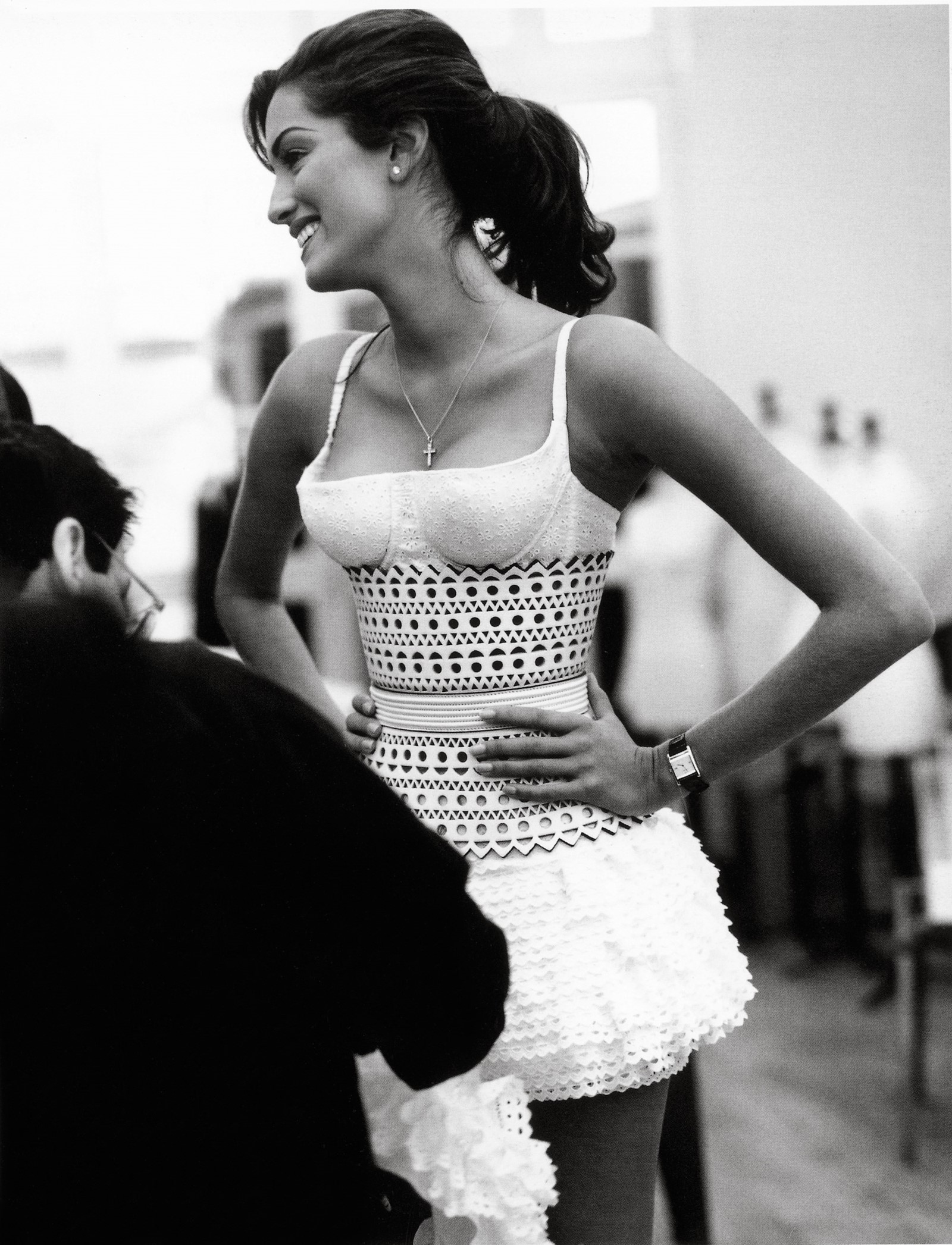

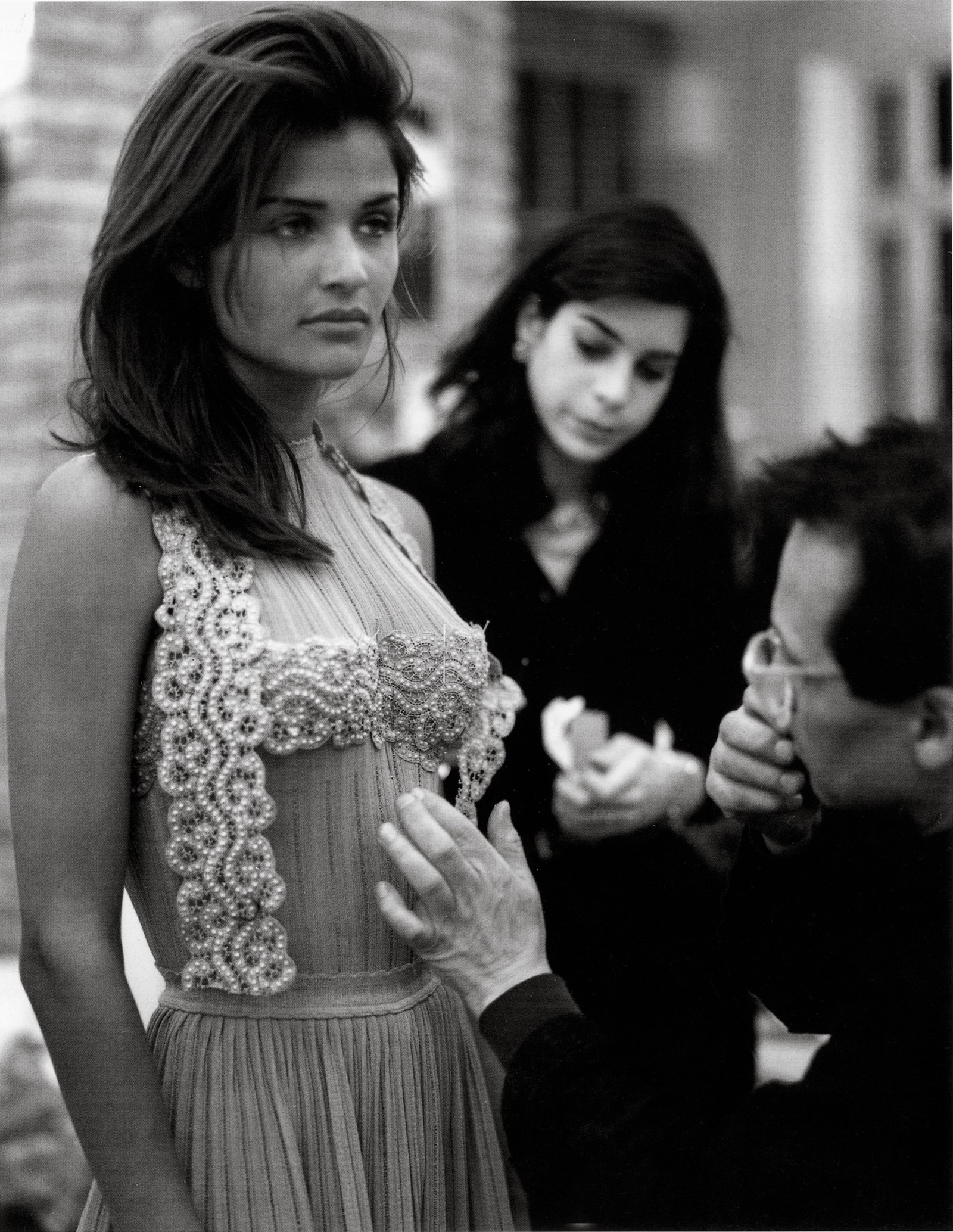

This collection has also come to emblemise Alaïa’s style because, unlike the incomplete documentation of others, it was painstakingly recorded for posterity. Alaïa’s friend of three decades, the publisher Prosper Assouline, took intimate photographs throughout its creation, compiling them into a book expressively titled The Secret Alchemy of a Collection that charts the entire process from inspiration to presentation. Limited edition to begin with, it has been reissued alongside this summer’s exhibition as Alaïa: Livre de Collection. The start focuses on the physicality of Alaïa’s atelier – fittingly, as it was the first point of departure – even including a still of the French film star Arletty in a butterfly jacquard dress from the 1940 film Tempête, which Alaïa used as a basis for a series of knits in his previous collection. The images then unspool, through the planning, creation and fitting of the outfits, as well as backstage shots from the April show itself. We see Alaïa fitting toiles, cutting patterns, patching fabrics. He referred to himself as a bâtisseur – a builder – and here, in these remarkable images, we see him literally building his outfits on the bodies of his models.

And of course, those models, and this show, included Alaïa’s cabine of supermodels. His perfect clothes perfectly clothe the most perfect bodies in the world. 1992 was the height, arguably, of the whole supermodel super-phenomenon, and on that balmy April day in the Marais, the roll call was stellar: Helena Christensen, Yasmeen Ghauri, Carla Bruni (more recently Sarkozy), Eva Herzigová, Naomi Campbell, of course, and Veronica Webb. The show was presented, with Alaïa’s idiosyncratic disregard for the conventions of fashion, in April 1992 rather than October of the previous year alongside every other designer. The press and buyers still came, the clothes still sold. “Whenever the clothes come in, they sell,” Gene Pressman, then executive vice president of Barneys New York (and grandson of the original Barney), told The New York Times among rails of clothes after the show. At the same time, fresh from the show, Veronica Webb was pawing through said rails, trying garments on. It took two people to lace her into pieces, wrapping and tying corsets, like visions from that other century, via Dangerous Liaisons. “If you want to know why models love wearing Azzedine’s clothes, just look at how we look in them,” Webb declared. Which serves as succinct explanation for Alaïa’s continuing appeal, early or late, then and now.

The Influence

Many garments popularly associated with Azzedine Alaïa’s style were either introduced in or refined through this important and tightly edited collection: the balconette brassiere; the corset-jacket laced like a pair of Victorian boots through metal hooks; the ‘Diabolo’ belt in leather punched with patterns like lace; the short knit dresses inlaid with a scrolling ribbon and heart. (Later, they would spin into entire dresses cross-hatched with trompe l’oeil ribbons.) The influence of these clothes still resonates across the decades – oddly, for designs created to recall the 1700s, they entirely encapsulate the early 1990s in their consciousness of the body.

But this show also acts as a riposte to those who reduce Alaïa’s output to these aforementioned body-sculpting and clinging shapes: there are atypical outfits, like the long, easy dresses in striped silk that recall both the djellabas of Alaïa’s own north African childhood and 18th-century men’s undershirts, here worn as easy split dresses over (and under) corsets, and hems that dropped emphatically to mid-thigh, hugging the figure fluidly. Alaïa’s enduring influence on designers is mirrored by Pompadour’s influence on Alaïa – you could intuit her aesthetic imprint even 25 years later, in Alaïa’s Autumn/Winter 2017 haute couture collection. A volume-pumped gown in undulating bands of velvet and tulle was “très Pompadour,” Alaïa told me, flitting through racks of his couture pieces a day after that stellar show and fluffing out its near-weightless skirt. It wasn’t an isolated incident: a whole section of Alaïa’s current exhibition at London’s Design Museum focuses on volume, demonstrating Alaïa exploring 18th-century levels of grandeur both before, during and after this Rococo ode.

The Pompadour-patinaed clothes of Spring/Summer 1992 are currently back on display in Azzedine Alaïa’s glazed Marais showroom, where they were first premiered: this time, they’re on mannequins rather than models, and certainly (unfortunately) not on rails. Nevertheless, they look as vibrant and fresh as they did 26 years ago – and as enticing as Pompadour did 250 years prior.

Alaïa: Livre de Collection, with text and photography by Prosper Assouline, is published by Assouline. The Secret Alchemy of a Collection is on show at Galerie Azzedine Alaïa, Paris, until January 6, 2019.