“Always yes, Caresse” was her motto – and as a new book by her great-granddaughter demonstrates, it served this heiress, inventor, publisher and hedonist very well, writes Tish Wrigley

“Caresse Crosby has all the makings of a legend,” writes her biographer and great-granddaughter Tamara Colchester. “Yet history has not chosen to remember her in that way.”

Today ‘legend’ is a term bandied about with wearisome frequency, but with Caresse it takes flight. Her 78 years encompassed two centuries, two continents and two world wars, three husbands and three evolving identities. She invented the modern brassiere, founded both a pioneering printing press and a world peace organisation and hosted New York’s most legendary party, the Surrealist Ball in 1935. Starting life in Boston as a wealthy descendent of the first Puritans to land in America, she ended it in Rome, as Principessa di Roccasinibalda.

Colchester’s debut novel, The Heart is a Burial Ground, takes the sensational facts of her great-grandmother’s life and weaves them into an elegant rumination on the impact of a life lived far outside the conventions of her time. The story is one of love, desire, glamour, and also neglect, abuse and a legacy of shame. In Crosby’s indifference to social mores can be perceived both courage and cruelty, in her openness to every experience – “always yes, Caresse” was her motto – can be found both inspiration and an absence of discrimination or compassion. In Caresse’s story, we see the vivid explosion of an extraordinary life; in Colchester’s tale, we witness the aftermath.

Seminal Moments

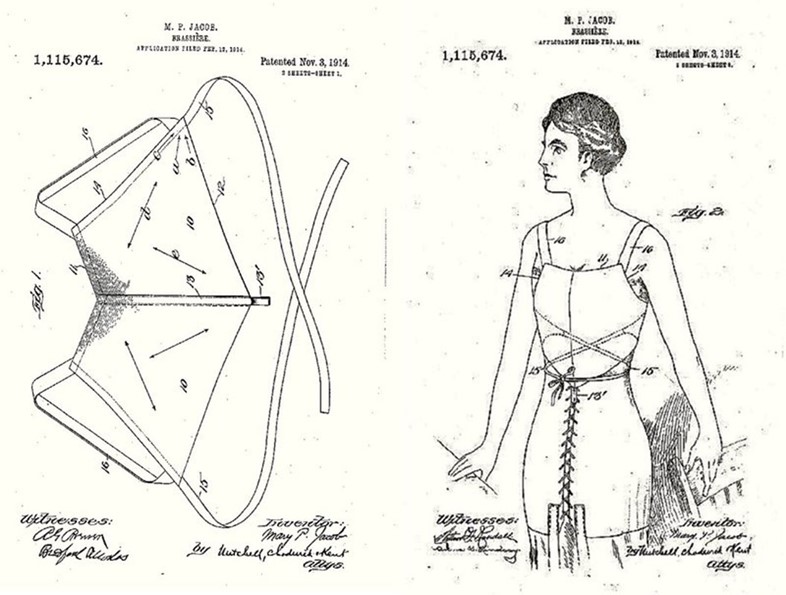

Born Mary Phelps Jacob in 1891, the young Caresse seemed destined for a quiet life, marrying the wealthy Richard Peabody in 1915, having two children and sinking into the anodyne social whirl of upper-class Boston. She flirted with notoriety in 1910 when, frustrated with the constrictions of her whalebone corset, she sewed together two pocket-handkerchiefs and some pink ribbon to create a prototype bra. Based on its instant popularity, she was awarded the first patent for the modern bra, which she eventually sold for a pittance to Warner Brothers Corset Company, who went on to make millions.

Her life was transformed in 1920, with the arrival of a young soldier seven years her junior. This was Harry Crosby, 22-year-old war hero, wealthy scion of a prominent Boston family and nephew of J.P. Morgan. He met Caresse – then known as Polly Peabody – at an Independence Day fair where she was acting as chaperone. He told her he loved her in the Tunnel of Love, she succumbed two weeks later, and after two years of scandalising Boston high society, her husband granted a divorce and they married and sailed for France, Polly’s two children in tow. “For the first time in my life, I knew myself to be a person,” she wrote. This person needed a new name, and after toying with Clytoris (later bestowed on a beloved whippet), Polly was reborn as Caresse.

They headed for Paris, already home to the most outlandish antics known to the century, but the Crosbys outdid them all. Harry got a job at J.P. Morgan, and every morning Caresse would row him to work along the Seine in a red canoe – “good for the breasts!” she explained. The bank job didn’t last – instead the couple sent a telegram to the elder Crosbys reading “Please sell $10,000 worth in stock. We have decided to lead a mad and extravagant life.”

And what a life – their friends included Salvador Dalí, Picasso, Constantin Brâncuși, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway, Walter Berry, Henri Cartier Bresson, Max Ernst, Anaïs Nin and all the students at l’Academie des Beaux-Arts, at whose annual ball Caresse arrived bare-chested, in a turquoise wig, riding an elephant. They founded a printing press – Black Sun Press – initially to publish their collections of love poetry to each other, before expanding their repertoire to include Joyce – with illustrations by Brâncuși – Lawrence, Kay Boyle, Ezra Pound and Hart Crane. They preferred to entertain guests in bed, dressed in magnificent dressing gowns, their whippets Narcisse and Clytoris between them, all four with gilded toe nails and laden with jewellery. Champagne and caviar would be served before everyone took off their clothes and had a communal bath. They smoked opium, had multiple affairs, travelled the world, wrote poetry, annoyed Edith Wharton, and spent money like water, disregarding anything that resembled contrivance or convention. A mad and extravagant life indeed.

Defining Features

If meeting Harry was the first pivotal moment of Caresse’s life, his death was the second. He died in December 1929 in a New York hotel room, entwined with his young lover Josephine, both with gunshots in their temples. An apparent suicide pact, the deaths caused uproar – not least because she was married, and his toenails were painted a bright red.

After his death, Caresse expanded Black Sun Press, taking a pioneering step into the then unfashionable paperback editions with works by Ezra Pound, Hemingway, Ernst, Dorothy Parker and William Faulkner. The war looming, she returned to the States, began and ended a marriage with an alcoholic 18 years her junior, enjoyed a long-running affair with the black actor-boxer Canada Lee and a short one with Buckminster Fuller. She hosted Salvador and Gala Dalí for 1935’s infamous Bal Onirique and put up Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin in her New York apartment, by all accounts teaching them how to write erotica.

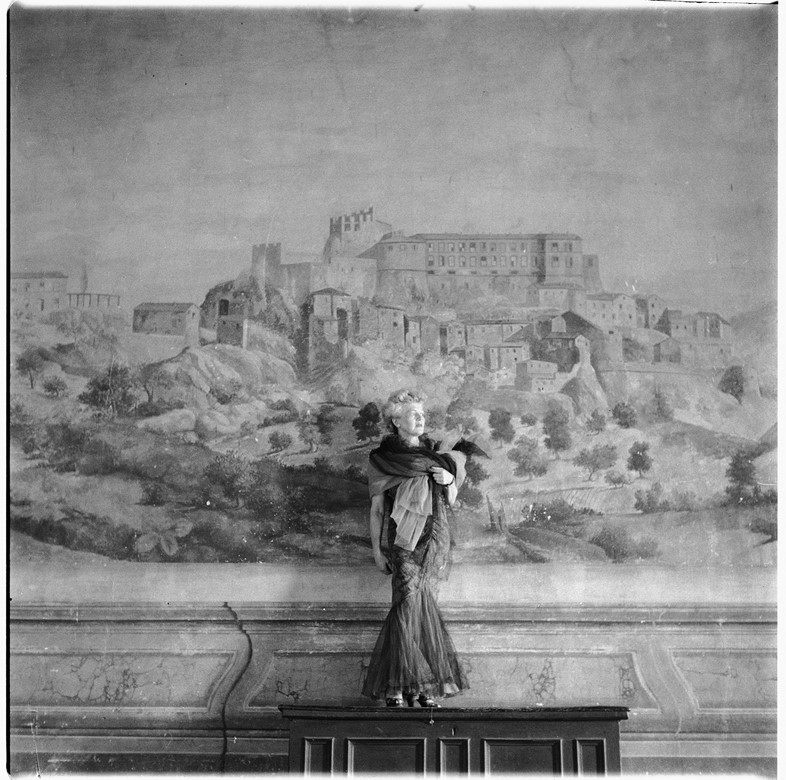

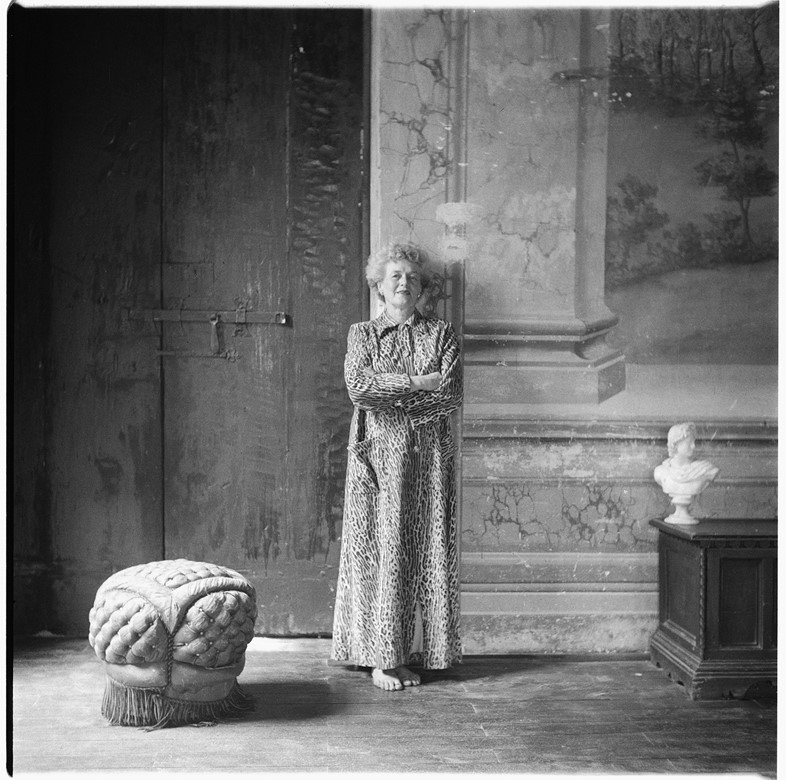

After the war, she returned to Europe and in the 1950s bought Roccasinibalda, a crumbling 15th-century Italian castle outside Rome that she transformed into an artists commune and a centre for world peace. Sincere political activism was combined with her enjoyment of extravagance – she was carried around the castle grounds in a sedan chair designed by Buckminster Fuller, and when going to see her daughter on Ibiza, she shipped a large black limousine and chauffeur over to the island for a single night’s stay.

She’s an AnOther Woman Because…

Caresse’s death in 1970 was noted around the world – Time magazine declared her “literary godmother to the Lost Generation of expatriate writers in Paris,” an apt description, but a rather muted one. At a time when the role of a woman was sharply defined and controlled, Caresse did not merely reject gender constraints, she acted as if they did not exist at all.

Her 78 years were spent pinballing across the world, shifting identities, living vibrantly and often violently, and disregarding obstacles with the single-minded verve of the courageous and extremely wealthy. Her claim that “money weighed very little in the balance of my decisions” is best explained by the reality of her large inherited wealth – perhaps it is easy to do extraordinary things when the pot of gold is inexhaustible, and runs to renting elephants and buying Italian castles. However her fiscal viability does not explain the technicolour of her life and relationships – for that, she must take the credit. “She was a pollen carrier,” remembers Anaïs Nin, “who mixed, stirred, brewed and concocted friendships.”

For Colchester, writing both as an admirer of her great-grandmother and as witness to the devastating impact of her actions, her feelings towards Caresse are complex. “Caresse’s life opens the door on the interesting intersection between desire and the responsibilities of motherhood,” she says. “The former begets the latter, and the latter often seems to obscure the former. Caresse did not allow that. She wanted to remain desirable, and there is something satisfying about seeing a woman who does not allow age to dim her radiance. However, there are also some very powerful consequences.”

The Heart is a Burial Ground by Tamara Colchester is out now, published by Simon & Schuster.