In March 2016, Vivienne Westwood announced that she was changing the name of her main-line collection to Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood. Prior to that, it was Vivienne Westwood Gold Label, shown in Paris since the mid-Nineties. This, then, was a public acknowledgement of Kronthaler’s huge creative input over the past quartercentury. To those who know her, Westwood has never made a secret of that. The more accessible Vivienne Westwood men’s and women’s collections, formerly known as Red Label and Man respectively, and still designed by Westwood and shown under her own name, now take place in London in January and June. But the Gold Label was always the jewel in the company’s crown. Elsewhere, the fashion industry is dominated by corporate superpowers in search of designer talent to creatively direct houses founded generations before, often with no obvious connection to them, however brilliant they may be. Westwood is rare. With Kronthaler and managing director, Carlo D’Amario, she owns and controls the company she founded and has chosen to pass the reins of one of the most famous labels in history to a man whose name few outside of fashion recognise – or even know how to pronounce. She has long dubbed Kronthaler “the greatest designer in the world”. He is also the love of her life, and she of his. They married in 1992. The word ‘authentic’ is overused to the point of meaninglessness. But Vivienne Westwood and Andreas Kronthaler, both personally and professionally, are the living, breathing embodiment of just that.

We meet at the Wallace Collection in central London, a place long enjoyed by both. It was here that Westwood launched her powerfully beautiful manifesto, Active Resistance to Propaganda, the basic premise of which is that our experience and understanding of art and culture is the antidote to propaganda and therefore key to the protection of the environment and the human condition. Her work, too, has been indebted to some of its fêted artworks, from furniture to painting. She is late. He is early, wandering around the space, excited by the fact that schoolchildren are in attendance sketching their own interpretations of its marvellous contents. Later, he will tell his wife about that. They share a desire to inspire younger generations, to pass down their knowledge. Westwood has an almost evangelical need to do so, and her influence, over fashion and beyond, is unprecedented.

Vivienne Westwood tells stories, in person and in her work. She is a passionate narrator, and her vivid imagination, heightened instincts and intelligence hold, and often dominate, the room, as she flits from one subject to another, as passionate about politics as she is about clothes. Before I inevitably adopt the position of gooseberry par excellence, then, Kronthaler and I have an opportunity to talk in the museum’s pretty courtyard café.

The subject is his latest collection, shown in Paris in March, and his most openly autobiographical to date. He lost his father last year – his mother died more than a decade ago – and he recently cleared the family home, which gave him the distance needed to embrace his own past in a way he hadn’t felt able to before. “Yes, it was something very personal,” he says now. “When I was growing up, I very much loved the Art Nouveau period. I collected china and old clocks. I had all these old clocks everywhere.” This is not the most predictable way for a young boy to decorate his private space, it has to be said, but his mother owned an antiques shop and it was from her stock that Kronthaler sourced these treasures from the Twenties and Thirties. “I remember once there was an Art Nouveau carafe, with lilies painted on it in gold, and eight glasses,” he says. “I loved it so much. It was on a silver tray. And then, one day, it was gone. I was so upset. I cried and cried. I think I was about eight. Anyway, my mother had to call the lady and ask her to sell it back to her.”

As an adolescent, he rejected any such ornamentation. “Then I didn’t like it any more for over 30 years,” he confirms. “At art school, I thought it was all kitsch rubbish. But as a child my bedroom was full of Klimt posters.”

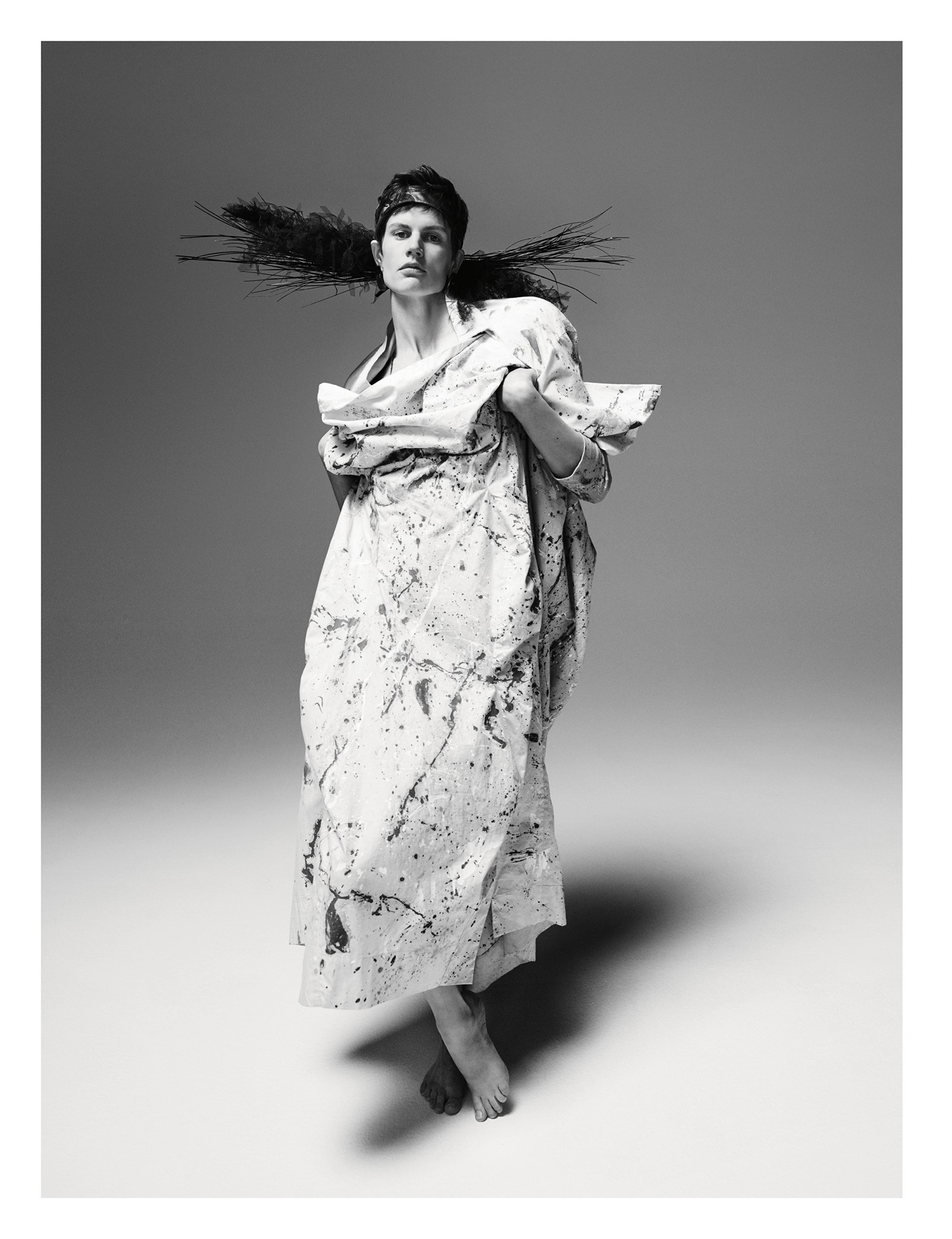

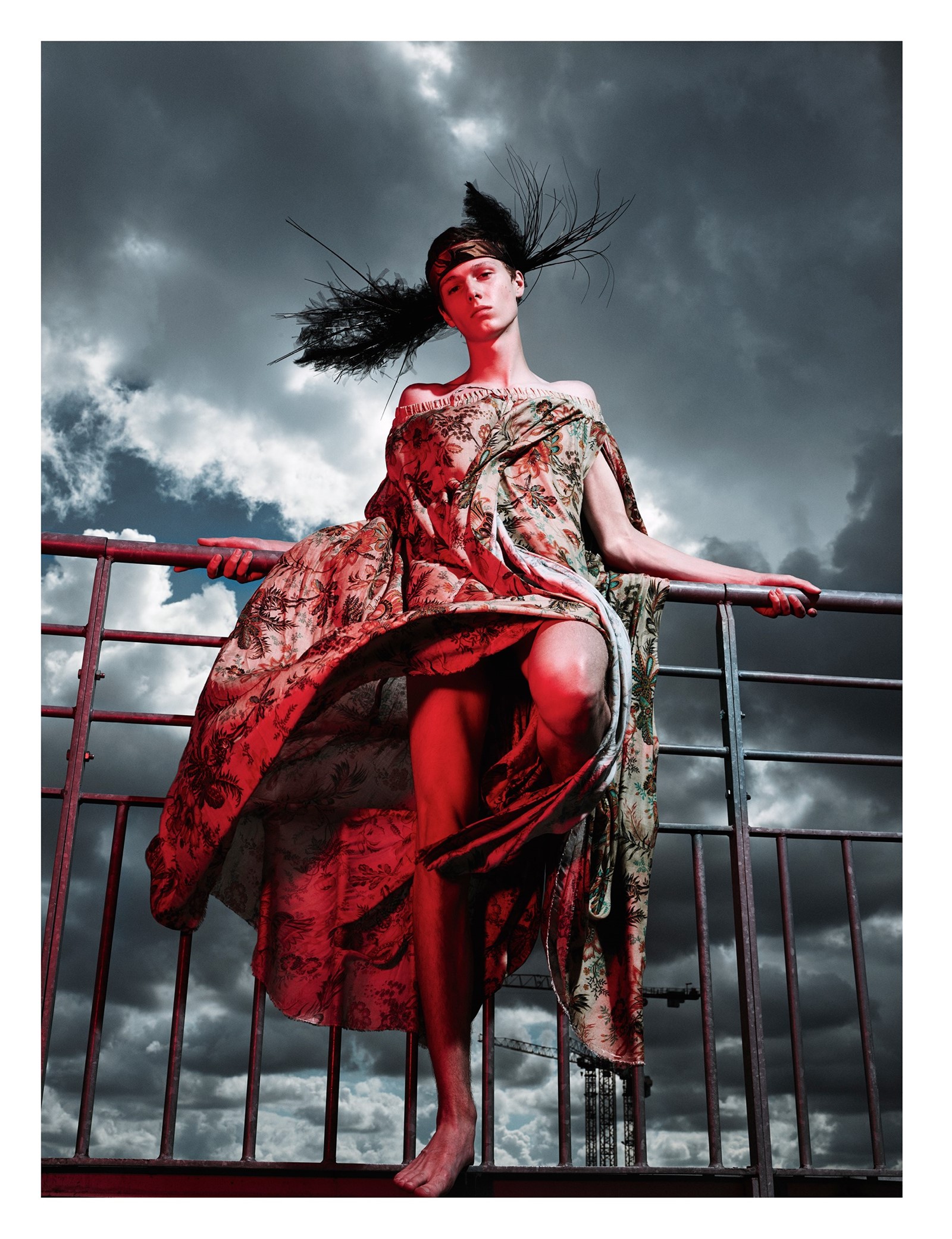

In pride of place on his wall was Klimt’s Danaë, inspired by Titian’s painting, Danaë Receiving the Golden Rain (Kronthaler describes her not quite so politely as “receiving the golden shower between her legs” and that sexual implication is in fact there). As a reference, it’s all present and correct in his latest collection – in the shimmering gold epaulettes, fringing, bows, piping and tassels on a Jester top; in the paint-splashed maillots; and, most dramatically, in the metal-thread garlands of leaves winding their way across an overblown black taffeta gown.

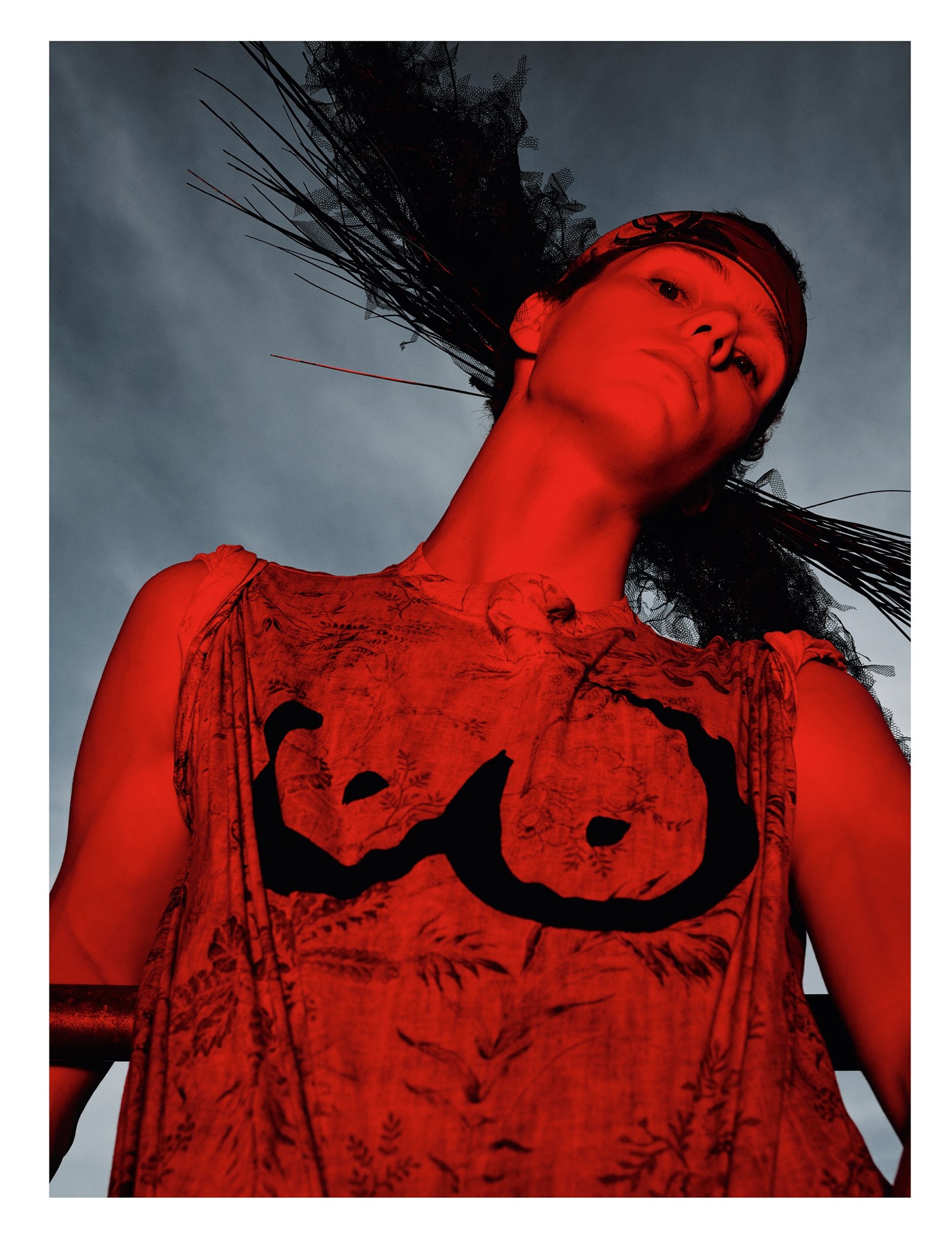

Next Kronthaler came across “two children’s outfits from the Wiener Werkstätte”. One was a felt two-piece costume, raw cut, decorated with Alpine flowers, and the second “a glorious little dirndl”. “We changed the cut and kept the childish proportions,” he states. And so he has. Here is a cropped jacket and skinny, high-waisted pants, there a zoot suit. Edelweiss, meanwhile, dance on pretty smocked skirts, a patchworked silk jacquard dress and oversized knits. There are hearts worthy of a modern-day Heidi too – frilled, woven, embroidered, appliquéd or in the form of heavy brass jewellery. It could all so easily tip over into the cloying, but the sheer energy, flamboyance and, above all, audacity on display make it anything but. Penises scrawled here, there and everywhere also cut through any sugar-coating.

“A penis isn’t a problem,” Kronthaler says happily. Like his wife, he is in no way prudish. Indeed, Westwood herself is fond of a penis: Back in 1989, buyers walked out of her Spring/Summer 1990 show due to a sequence of underwear defaced with similar phalluses. She’s also used them as buttons and jewellery.

With that in mind: “I did the invitation for the menswear collection in Milan one year, where Vivienne and Andreas nearly got arrested,” says Tracey Emin, who has modelled for Westwood and been friends with the couple for years. “The card had a really beautiful penis that I’d drawn – but an erect penis – and when it was sent out the authorities wanted to know about it. But it was Vivienne and Andreas. You know, it was funny.”

It would be entirely misleading to describe Kronthaler’s, or indeed Westwood’s, work as iconoclastic, although it has erroneously been defined that way. Provocation is clearly a large part of their story, but it is never forced. They evoke extreme emotion – and opinion – but to them that is natural, and indeed important. They also demonstrate great respect for any source of inspiration and for history, however – their own and that of the broader culture.

Vivienne Westwood arrives. “Here she is. The famous Vivienne,” her husband says, smiling. “I’m not usually late. But yeah,” she replies. For the first time, Westwood – who is dressed today in patchworked men’s shirting and has long been the best possible advocate for her clothes – was cast by her husband and modelled the collection in question. “He asked me to and I said yes,” she told Vogue Runway immediately before it was shown. “You know, she’s been doing the campaign for years,” he said. Diversity, another current buzzword in fashion, was something practised by this designer pairing many years before it was adopted by the industry more widely, and that applies to skin colour, gender, body shape and age alike. Westwood and Kronthaler like unisex clothes, too, not least because they mean less waste: buy fewer clothes and share them – “Unisex is good for the environment” Westwood’s blog (climaterevolution.co.uk) declared in May 2016. Women in boxer shorts, men in skirts… It’s such familiar territory now, but these two have been doing it for decades. “I love going out in boxer shorts,” Vivienne Westwood says.

Putting their money where their mouths are in a more literal sense still, both Vivienne Westwood and Andreas Kronthaler appear in Juergen Teller’s print campaigns for Kronthaler’s collection and for Westwood’s own. They look magnificent together. The collaboration with Teller is ongoing and celebrated in an exhibition at the Vivienne Westwood flagship store on East 55th Street in New York this month.

Teller encountered Westwood before Kronthaler did. He met her on a shoot for French Vogue in 1993. She later told him that the resulting image of her sitting on a park bench was “one of the sexiest pictures anybody had ever taken of her at that time,” he says. The two worked together again on several more occasions before the photographer visited her home and shot Westwood with Kronthaler and her former muse Sara Stockbridge for i-D. “It was just a really lovely day photographing them,” Teller remembers. “The house they live in was really nice and that was the beginning. I said, ‘I think if you want me to do the campaign you both should be in it. You wear the clothes fantastically well.’ Vivienne’s response was, ‘What a great idea. It will be cheaper,’” he laughs.

“Vivienne is such an inspiring soul. The way she looks, everything. What she stands for and what she has done in life” – Juergen Teller

“It’s really easy with us. We like the same things,” Teller continues. “Vivienne and Andreas have always had this sense of freedom and engagement with whatever we think is best for each scenario. I’m sure if they were starting out they’d have just the same attitude. It’s what it always was, the confidence to do what they believe in without compromising. I guess a big difference between them and other people is that they’re their own boss; they don’t have somebody looking over their shoulder and saying something, they don’t have to talk to their CEO. I think that’s the greatest strength. They can do whatever they want; we decide on the day. You know, I can’t photograph a camel – there have to be handbags and clothes. But we just use ourselves. I think the bottom line is to have fun together. They have an extremely good eye for casting. They do all the casting for their shows, they’ve got a big fan club and followers, and that all comes across. Sometimes I bring in people who they also find exciting.

“Vivienne is such an inspiring soul. The way she looks, everything. What she stands for and what she has done in life. I’ve been photographing her for so many years, through all the different collections, and always found her incredibly beautiful – her skin, just the way she looks. She is such a good looking, proud, mature woman.”

In 2009, and this time for a personal project, he captured Westwood naked: the images were published large format and shown at the ICA’s exhibition of his work, Juergen Teller: Woo!, in 2013. “I haven’t photographed anybody her age naked before. It was just an experiment I wanted to do. She was like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve never thought about that!’ And then she said, ‘Why not? Let’s do it. I trust you completely. I’m curious how I would look.’”

As for her husband, “We have a very, very lovely relationship, Andreas and I,” Teller says. “We understand each other very well. I come from Bavaria, he’s from Austria. We speak very happily in our Austrian-Bavarian way. We share the same language.”

If ever proof were needed that creative freedom reaps rewards, these campaigns are surely the finest examples of that. Westwood and Kronthaler, alone or surrounded by friends and professional models, from the famous to the barely known, all resonate with individuality, originality and, seen as a whole, are a celebration of brilliantly dressed humanity in its many different guises.

Pamela Anderson – a better-known subject who has appeared on more than one occasion – came into the fold when she was asked by Westwood to sign her Free Leonard Peltier petition. Peltier, a Native American, is an activist for the American Indian Movement who was imprisoned for the murder of two FBI agents during a protest siege. Convinced of his innocence, Westwood has campaigned for his release for many years. “Soon after I was invited to a Vivienne Westwood fashion show,” Anderson says. “We related to each other because we used everything we are, and everything we had and have, to try to make a difference in the world; a lot of gut instinct as well as art, intelligence, culture. I love shooting with them because it’s like telling a story. Vivienne and Andreas are always conveying a message, maybe Vivienne more than Andreas. Andreas loves fashion and Vivienne is political. I think it’s quite interesting to have these beautiful clothes on different types of people. I loved our last shoot in Hydra with all its history, but others have been very spontaneous: the three of us dressing each other in a very small space, in our underwear or less, pulling on stockings. Then Vivienne narrating the shoot: ‘We are warriors!’

“Vivenne and Andreas are a normal couple, full of passion and disagreements,” she continues. “They have separate interests. Vivienne is a force for culture, and Andreas is too. They both know so much about so many different things. Andreas is also very calming and reminds us to enjoy the world, as messy as it is. It’s beautiful and we must live joyfully. You can see that in his work – joy. I love being around them. They live very simply, they do not overindulge. They balance each other. These are only my observations but I feel close enough to them to say this. I think theirs will be one of the most fascinating love stories history will remember.”

Andreas Kronthaler and Vivienne Westwood grew up in different parts of the world but their respective upbringing shares distinct similarities. He was born on 26 January 1966 in Tyrol. “It was very liberal, carefree,” he says. “It was a rather idyllic world, in the mountains in Austria. Looking back one always sees childhood as a fairytale, and I suppose it was. I could roam around free. I had nice parents.” His father was a blacksmith, his mother dealt in antiques. “They were from opposite backgrounds. She was a farmer’s daughter and he was a workman. She married outside of her world. My father was a very artistic man, very good at what he did.” Kronthaler Senior travelled with his son around Europe, installing wrought-iron balustrades, chandeliers and more that he had made for churches. He would shout, ‘Andreas, Andreas, I’m going, do you want to come?’ It was in the van. We would go quite a long way, around the Tyrol, the South of Germany, Italy… I was most happy when everything was moving because I could look at things. I’d see churches and buildings and cities.”

“By the way,” Westwood chips in, “when he came home from school, if his father wasn’t there, Andreas made armour in his father’s forge, for himself and for his friends.” Her eyes brighten with admiration as she recalls this anecdote.

At age 14, Kronthaler went to art school in Graz, where he studied to be a goldsmith alongside his academic qualifications. That took five years. During this time, he experimented with various media, including sculpture, installation, sewing and textiles. To support himself through school, he made clothes and sold them in local stores. After completing his diploma, he entered the University of Applied Arts, Vienna to study industrial design. He continued his clothes-making business to pay his way, developing his tailoring skills. Soon he realised that his interest was in fashion above all else and reapplied for that course. In 1988, he met Westwood, who arrived to teach at the university in his first year.

While he had seen her work in magazines, Kronthaler was by no means an obsessive Vivienne Westwood fan, and was unaware of the history of punk. Still, while describing his first impressions of the woman he would go on to marry as love at first sight would be putting words in his mouth, there was certainly a spark. He addresses his wife directly: “There was quite a high windowsill in the studio and I was sitting up there. And you came in and you were looking very, very special. The way you looked, I thought, was incredible. She started to talk and it was the talk that captivated me more than anything. I just agreed so much with everything she said. It was a lot about history and how important history was and I was all fire and flame and thought, ‘Yes, this is where it’s all at, it’s history, it’s the best.’ Nobody valued that stuff until then. I didn’t have teachers who said, ‘Go back and look at this and copy it or make something out of it.’ They always told you to do your thing, be yourself. I didn’t know what they meant. What does it mean, ‘Be yourself?’” Ironically, it is difficult to imagine anyone more comfortable in their own skin than Andreas Kronthaler. Instead, and like Westwood, he is almost disarmingly honest, cutting through any surface niceties as sharply as a razor blade and going straight to the heart of things with a lightness that belies the often profound nature of his thought process.

“It’s a terrible thing,” Westwood adds. “It’s the new millennium saying, ‘The past is rubbish, we’re all perfect, we’re moving towards paradise. All you’ve got to do is catch the latest thing, keep on going, because everything is automatically going to get better and better. We’re all going to have two cars, we’re all going to have equality. We’re all equal, equally talented…’”

“I remember you started with a historical shirt,” Kronthaler continues, “a copy of a shirt made out of rectangles, this kind of rustic shirt with a gusset under the arm. And then the next thing to do was to individualise it, put something of your own into it.” Not insignificantly, that lesson informs both of their work some 30 years later.

“It was 500 years old,” Westwood recalls, “and what I actually said was to try to make it for a machine industry, because you can make it beautifully by hand but to work out how to make it in an industrial way, how to get that plaquette sewn properly, is more difficult.”

Vivienne Westwood (née Swire) was born in Glossop, Derbyshire, on 8 April, 1941. Her father came from a long line of cobblers; her mother worked at the local cotton mills when she wasn’t at home looking after her children. “I had a very, very loving mother and father who were also in love with each other,” she says. “They put their children first all the time. I lived between two villages and my mother, when I was a child, just used to put me over the wall, on the main Manchester-Sheffield road but right in the middle of the Pennines. I was immediately in a wood and I could climb a bank into the meadows. And she wouldn’t see me all day. I know an awful lot about the countryside and making miniature gardens. I used to spend the days underneath the trees on the moss. I was also mad about reading. I remember once my mother gave me five shillings to drop out of the mobile library that drove round to my village. She did it because otherwise I wouldn’t get enough fresh air. That was easy. I borrowed my friends’ books and read outside.” From an early age, she demonstrated the resourcefulness and determination that continues to drive her now.

It was a very different time. “You know, people don’t go around like they did before. After church, after Sunday school, we’d walk all over the hills in little white dresses and straw hats, and sometimes we’d have a picnic and stay by the pool and go in the water. We’d watch the little lambs at Christmas when they were born in the snow. There’s nothing better you can give to a child than to be born in the country. And it gives you a confidence as well. When I came to London I was really astonished by how frightened everybody was. ‘We can’t go in there’ and all this.”

“There’s nothing better you can give to a child than to be born in the country. And it gives you a confidence as well. When I came to London I was really astonished by how frightened everybody was” – Vivienne Westwood

“It’s true what Vivienne says,” Kronthaler agrees. “You don’t have that when you grow up in the countryside. You’re much more fearless.”

Westwood continues: “I went to a dance [in London] when I was 17 and I looked great, I did look good. And somebody came and danced with me and that was that, nobody danced with me again all night. That was it, because I didn’t dance like them. It was so cliquey. It was completely different up in the North, or in Manchester; we toured around with these real, proper bands, and kids would jive around outside. We had no worries about confidence. The world was my oyster. I didn’t feel like my back was against the wall like the kids in London did.”

By this point, her parents had bought a post office and moved to South Harrow in Middlesex. After leaving school at 16 and studying fashion and silversmithing for one term at Harrow Art College, she worked in a factory for a short while and then went to teacher-training college. In 1962 she met and married Derek Westwood and had their first child, Ben, in 1963. The marriage lasted three years, during which time she taught at a primary school and made jewellery that she sold on Portobello Road. She soon met Malcolm McLaren (then Edwards) and became pregnant with her second son, Joseph, who was born in 1967. In 1971 McLaren opened a shop called Let It Rock at 430 King’s Road, London, and Westwood filled it with her designs.

“Vivienne and Malcolm were selling Teddy Boy suits and brothel creepers to boys and girls to start with,” recalls Michael Costiff, who opened the World boutique with his wife, Gerlinde, as well as fronting the Eighties nightclub Kinky Gerlinky. “They were really good fun. They were full of changing the world. They didn’t approve of a lot of things, but there were a lot of things not to approve of.” Margaret Thatcher, the miners’ strike, power cuts and the three-day week presumably among them. “The King’s Road was really buzzy. It was the centre of everything, everyone went there. I think the first thing I bought was a skin-tight, wet-look T-shirt. And she did these fantastic Oxford bags [loose-fitting trousers] that were pegged at the bottom. I realised later that you can almost reach into the bags and feel a Vivienne Westwood outfit by the quality. They always used the most beautiful fabrics and everything was particularly well made. It was all properly done.” This is all the more remarkable for the fact that Westwood is entirely self-taught.

It is the stuff of fashion history that, in 1972, and in line with the fashion that was developing its own distinct character, the name of the store changed to Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die, and then, in 1974, to Sex. When, in 1976, the Sex Pistols, managed by McLaren, released God Save the Queen, it became known as Seditionaries: Clothes for Heroes. In the past, Westwood has only ever reluctantly spoken about the impact of punk although more so since the death of McLaren in 2010. In an interview for the Independent newspaper in 2011 she told me: “Johnny Rotten’s songs really were very clever, weren’t they? ‘No future. Your future dream is the shopping machine.’ That’s what he was on about and that is what we are. We’re a consumer society.” In 1980, however, disillusioned with the mainstream’s adoption of the movement and its principle protagonists, she renamed Seditionaries World’s End. “I realised that they weren’t real anarchists like we were. They just wanted to be a gang and smash up anything to do with the older generation, like kids do.” That name – and indeed the clock that hangs on its façade telling the time backwards – remains.

However establishment punk had become, “The fashion press were really, really slow catching up with Vivienne,” Costiff remembers. “The first time they did was when she did the pirate look [Pirates, Autumn/Winter 1981, was Westwood and McLaren’s first runway show, held at Olympia in West London] and that was because she did a lot of quite frilly shirts that Tatler and Harpers & Queen really loved. They wanted those shirts and then they started to look at her other things. Also, Sex and Seditionaries were quite fearsome to step into. We had friends who were scared to go in and would ask us to take them there.”

The milliner Stephen Jones, who worked with Westwood sporadically in the early years, understands this sentiment only too well. “I used to go to Sex on the King’s Road and to Let It Rock when I was still at school,” he says. “I’d put my head through the door and get very frightened and leave right away. I knew Sex from my first term at Saint Martins, but when it was Seditionaries I bought things there, I really got to know the world of Vivienne – and Malcolm. They were the only clothes made by a fashion designer that were relevant. Nobody else was important.”

The tweed crown that was to become one of Westwood’s most instantly recognisable signatures was their most well-known collaboration: Jones made the original pattern and prototype, though the concept was quintessential Westwood. “She said, ‘I’ve got this idea of doing some crowns out of fabric’ and told me about the tweed,” Jones explains. “So we worked on the pattern and developed a sample. Maybe one of the funniest times I worked with her, though, was when she started showing in Paris. I hadn’t done hats for her but was a guest. I’d borrowed Jeremy Healy’s Westwood outfit to wear because I couldn’t possibly afford it myself. We thought we would go backstage and say hello and Vivienne was there. It was absolute chaos, nothing was ready, everything was being finished off and she said, ‘Oh, you’re Stephen Jones, you can sew can’t you? Here’s this thing, can you go over it? There’s the pattern and there’s the fabric.’” The item in question was a mini-crini, first shown for Spring/Summer 1985, and inspired equally by Stravinsky’s Petrushka and the Victorian crinoline.

“The first time I remember seeing Vivienne Westwood, she was sitting on the doorstep of her shop on the King’s Road, surrounded by other punk-ish figures,” says Suzy Menkes, Vogue International Editor, who has written about the designer’s work from almost the start of her career. “She had blonde curls, a mini-skirt and hefty boots. But all I really remember was the punk sexiness that surrounded her. You could almost smell it. Nobody seemed even faintly interested in selling anything. It is difficult for anyone today to understand the importance of the King’s Road and what it stood for: the breakdown of the aristocracy, which used to own the territory, literally and figuratively; the crumbling of the class system; the social revolution; the way the young and well-born joined the youth cult. Mary Quant with her geometric cut and mini-skirts came first, then the sensual romance of Ossie Clark. They were both part of the King’s Road world. Vivienne came a bit later at the beginning of the Seventies. Compared to today, everything was on such a small scale. Local, Chelsea, not even London. International? Not at all.”

In 1976, Westwood was photographed in the store with the Sex and Seditionaries shop girls Jordan and Chryssie Hynde, pre-Pretenders. Westwood is wearing stockings, suspenders, elevated platform-soled shoes and a man’s white shirt printed with the French Situationist slogan, Be Reasonable, Demand The Impossible. It would not be unreasonable to argue that this marvellously impertinent sentiment still drives her. Certainly, she is indefatigable. She is a patron and trustee respectively of the human rights organisations Reprieve and Liberty. She supports Amnesty International; the Environmental Justice Foundation; Friends of the Earth; Greenpeace (for which she created the Arctic Campaign logo); and the rainforest charity Cool Earth. She works closely with Ecotricity and this season will launch a ‘Switch’ campaign at London Fashion Week, reaching out to the industry’s great and good to persuade them to switch – as the name suggests – to green energy. She also supports the WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange, to whom she dedicated her Spring/Summer 2017 menswear collection. It’s a wonder she finds time for fashion. “Andreas would like to know how I do that as well,” she once told me.

“She had blonde curls, a mini-skirt and hefty boots. But all I really remember was the punk sexiness that surrounded her” – Suzy Menkes

Westwood came into contact with Assange through her support of Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning, the American soldier who in 2013 was convicted of disclosing more than 750,000 classified military documents through WikiLeaks. Her 35-year sentence was commuted by Barack Obama in January this year, and she was released in May.

“I see Vivienne every few weeks,” Assange says. “She’s very bright and tough. She’s also very modest. She doesn’t try to talk up her fashion as having a political or moral dimension. But if you look closely at some of her writing, and listen closely to her, going back to her punk days, she produces fashion that makes the people who wear it feel bold. Coming from another fashion designer, that could be an empty marketing phrase. For Vivienne Westwood, it’s not. It’s how she’s lived her life and how she chooses to live her life now. She not only wants to display courage but also has the capacity to design things and run a company. I guess that puts you in a reasonably good position intellectually to see what might be unfolding in the world and then emotionally to sympathise with it.”

By the mid-Eighties, Westwood and McLaren had gone their separate ways, which brings us back to her initial experience of Andreas Kronthaler. “We were very attracted to each other, I knew that,” she says. “When I was teaching I pretended not to be, but he was the one I wanted to see. He used to meet me off the aeroplane when I was there. I didn’t want the others to know that I favoured him. Because you were very, very talented as well. He was amazing.”

“It was so special, really,” Kronthaler says to his wife. “The world you introduced me to. Extremely special. I loved the way she saw it all. I loved the way you saw the body alone. I just appreciated it so much. Everything was always so sexy and so funny. It had so much humour. And I needed that. I thought that was a quality that wasn’t around and that nobody cared about. And it’s still like that now. I find it very rewarding when something is not only very well or beautifully made but also humorous, a bit out there, not all just straight down the line.”

In 1990, Westwood invited a group of students from the school to see her Portrait collection for Autumn/Winter 1990. From that point on, Kronthaler never really left her side. To begin with he slept beneath the studio, then based in Camden. “There was lots of space and I had a great time,” he says. “I remember I rolled out this fur in the evening and that’s what I slept on.”

“Not real fur,” Westwood is quick to point out. “They all left at seven o’clock,” Kronthaler continues. “There was this big hallway and boxes full of old stuff, archive. Every night I would go through it, being nosy. And that was when I got to know your things really.” Westwood moved her company to Battersea in South London soon after. It is still based there today.

The archive in question is extremely precious. It has paved the way for everyone from John Galliano to Alexander McQueen, and continues to be among the most referenced, from the runways down. In 1996, even Comme des Garçons acknowledged Westwood’s influence, creating a collection of Westwood patterns in Comme fabrics.

“Think of Rei Kawakubo’s revision of punk and plaid,” Menkes says, “and the huge platform shoes, which only came back to fashion life when Naomi Campbell fell off hers. I remember Vivienne, wearing her school-marm face, giving me a lecture about Venice and how the prostitutes wore platform shoes to be seen above the crowd. She was always good at getting sex and spice into her stories.”

And so, after punk and Pirates, came Nostalgia of Mud (also known as Buffalo), for Autumn/Winter 1982. Later, Westwood reinvented the dress codes of the British aristocracy – from hunting jackets to ermine collars, from the aforementioned crown to Harris Tweed. She transformed French Rococo paintings into signature corsetry and overblown skirts. In fact, she credits Kronthaler with the latter. “You should see him with the ballgowns and corsets,” she says, “in front of a stand with all this fabric, throwing it all around. Incredible. He’s amazing.”

Kate Moss recalls, “When I was growing up in Croydon it was all about Vivienne. I’d save up; everyone would save up and spend all their money from their Saturday jobs on Vivienne. So after weeks and weeks and weeks you might be able to get, you know, a pair of shoes in the sale or, ‘Oh, I got an Orb T-shirt. Oh my God, I got the Brigitte Bardot jumper in pale blue.’ It feels part of my life. That’s why I’ve always loved her clothes. Even if you’re just wearing a pencil skirt, there’s something going on. I have a black velvet Westwood corset and when I put it on it feels like a flashback to Nineties raves. That’s probably my favourite piece. I’ve got the Hangman jumper. I’ve got the Seditionaries shoes, and the Sex Prostitute shoes, which I wear a lot.”

“When I was growing up in Croydon it was all about Vivienne. I’d save up; everyone would save up and spend all their money from their Saturday jobs on Vivienne” – Kate Moss

Of the woman herself, Moss says, “She’s an amazing, strong woman yet so gentle and sensitive. When you have a conversation with Vivienne it’s a proper conversation and that’s what makes her so special. You talk about stuff, about family. She wants to know about your life and you feel part of hers.”

Moss modelled for Westwood throughout the Nineties, appeared in the Teller print campaign as recently as 2013, and is a friend. “When we did the shows, Azzedine Alaïa and Jean Paul Gaultier would be on the front row, and I just remember being like, ‘Oh my God! I’m walking in front of other designers!’ Everyone loved Vivienne. John Galliano wears Vivienne Westwood still, often head-to-toe. It wasn’t like shows now. It was so theatrical and it would go on for hours. It was more of an experience and just so much fun. And always shocking. I mean even when Vivienne was doing dresses it was shocking. There was always an element of rebellion.”

Given the longevity of her career, three generations of models have walked the runway for Westwood.

“My relationship with Vivienne began as I was reapplying my lipstick at the dinner table at La Coupole in Paris when I was about 23 years old,” says Susie Cave (then Susie Bick). “I was trying to hide it when Vivienne said, ‘I really like the way you’re doing that. It’s very old fashioned.’ I was so excited to meet her. I’d known about her since I was 13 and my best friend, Tammy, arrived at school after half-term wearing a Pirate outfit from head to toe. From that moment Vivienne became my hero: the unabashed costuming of that collection showed us young girls that we could be anything we wanted. There were no boundaries, no borders. Tammy had been completely transformed.”

“Vivienne’s shows were insane, just sweet anarchy,” Cave remembers, “and to be a part of them, so early in my career, gave me a voice; allowed me to be just the person I wanted to be. She was the ship’s captain, our supreme leader, and we were her godless figureheads, dressed in her crazy, scandalous clothing. I wouldn’t trade those years for anything. They made me.”

And here’s Jerry Hall on the subject: “I first met Vivienne when she had the Sex shop with Malcolm in the Seventies. I was engaged to Bryan Ferry then. I loved her clothes as the cut was so good and sexy. Her fashion shows with Andreas are the best – a bit of history and lots of magic. I adore Andreas; he’s an extension of Vivienne, who needed a worker as she moved on to saving the planet. Vivienne used to be a teacher and at Sunday lunches at my house she taught my children about how powerful 18th-century women were. Her clothes make women feel powerful and sexy and give dignity to age.”

“Vivienne’s show backstage was always so fun and light,” says one of the children in question, Lizzie, “with everyone hanging out together, having such fun. It’s nice that there’s no uniform look to it, that every look is individual, just like every girl. You get to play yourself, only amplified. Andreas is so supportive of Vivienne. Every time she had an idea, he would run with it and get so excited and inspired. They’re almost telepathic now. I think they’ve worked together for so long that they look at an outfit, then look at each other, and then add something. They don’t even really need to talk about it any more.”

Sam McKnight and Val Garland have been responsible for hair and make-up respectively for Vivienne Westwood and Andreas Kronthaler’s shows for more than a decade.

“There was one show where Vivienne showed me an old drawing, probably from the 16th century, of a man or woman running down the stairs with their hair on fire,” McKnight remembers. “Vivienne said, ‘Oh, I like the look of that.’ So off we went and made some flame-coloured hairpieces. She loved that and had her hair done the same way as the girls. I mean, you’ve got to love, admire and respect her commitment. She’s so committed to whatever she does. Then, there was another time when she picked up a plastic garment bag and said, ‘I wonder if we could work this into something?’ We did this floor-length braid with Vivienne Westwood plastic garment bags in the hair. There are no boundaries when you work with Vivienne and Andreas, which for me is an absolute delight.”

“I remember there was one time when Vivienne wanted all the boys and girls to feel like they were at a festival,” Garland says. “They had all come together from different walks of life to be at this gathering, so we had lots of different characters. One of the girls looked very pretty, like a slightly slutty secretary, so we wrote the words ‘posh totty’ in metallic lettering above her eyebrows. When we came to the line-up, Vivienne and Andreas were looking at things and when Vivienne got to the girl with the ‘posh totty’ eyebrows she smudged it off. It still looked good, like a rainbow, a colourful smudge. I just thought, ‘Well, if that’s what Vivienne wants, that’s what Vivienne wants.’ The next season I went to work with her and she took me to one side and said, ‘Val, I’m ever so sorry that I rubbed your make-up off at the last show, but I didn’t understand what it said. I didn’t know what posh totty was.’

“It’s almost like Vivienne and Andreas are one person,” Garland continues. “They’ve both got their individuality but they’re a unit and she will refer to him as he will to her, they look to each other for acknowledgement. It’s lovely. You can see they have great admiration for each other and indeed love.”

“There are no boundaries when you work with Vivienne and Andreas, which for me is an absolute delight” – Sam McKnight

It wasn’t long before Andreas Kronthaler moved into Vivienne Westwood’s home.

Andreas: “Vivienne would get up and prepare me a cappuccino with a lot of foam. And every day she would draw me a picture on the foam with food colouring – a tree or a face; sometimes very intricate scenes, sometimes a lot of colour, sometimes not.”

Vivienne: “Do you know how I used to make the foam? We had taps with these pink rubber things on the end of them and I used to get the milk and just squirt it with those and then make it hotter afterwards.”

Andreas: “It was incredible. I looked forward to it every day.”

The subject moves onto marriage, which they decided on, in the first instance, for practical reasons. Austria was yet to become part of the European Union and they travelled often. There’s a rare pause in conversation and Westwood looks at her husband.

Vivienne: “You want to talk about Croydon, don’t you?” The UK Visas and Immigration Office, Lunar House, is headquartered there.

Andreas: “We had to go two or three times. And they called us in separately. They were testing our relationship. We weren’t allowed to go in together. It was really brutal.”

Vivienne: “They wanted to know if you ever had any pet cats.”

Andreas: “What did I say?”

Vivienne: “You said, ‘Yeah, I’ve got a wardrobe full of them, drawers full of them.’” She’s laughing.

Andreas: “And there was always something like, ‘What did you do last Christmas?’ And Vivienne, you’d never remember it.”

Vivienne: “They said that they were going to believe we were really together even though everything I said was not what he said. I mean, I would get the colour of the carpet right and things like that.”

Andreas: “Not true Vivienne! You didn’t. I think we amused them.”

“I didn’t want to get married particularly,” Westwood continues. “I was against marriage. To me it was just part of the system, which I hate. I was really cross when Jordan got married. I thought I might have to sack her. I was with Malcolm for 13 years and we never married. But then I thought, ‘Well, it is actually possible. I’m not married to anyone else.’ Then, when we did get married, it made a big difference to me. Going through that ‘till death do us part’ thing. Since I did that, I’ve put Andreas first. He’s been my priority. Well, I’ve always been a one-man woman.”

“It’s like Vivienne says, it’s a commitment,” her husband concurs. “And maybe I felt the same as you felt when we married. And it still feels like that. You know, she’s what my life’s about really.”

Vivienne: “You love cleaning.”

Andreas: “You know, when I clean is when I relax. If I want to take my mind off something… Vivienne has never cleaned in her life.”

Vivienne: “I cook. I get the food.”

Andreas: “Vivienne is the cooker. She’s really good at it. I don’t think she knows where the hoover is.”

Their life is also about work, and their passion for work is only equal to their passion for each other.

“I don’t really use this word very often, but Andreas is just ‘darling’,” Tracey Emin says. “He’s lovely and he loves Vivienne so much. Their relationship is enchanted but also professional. Vivienne told me he came into her life when she was feeling a bit in the doldrums and he really woke everything up in the studio; he woke her up. They work very well together.”

Vivienne Westwood and I first met in the mid-Nineties at a point when her business was struggling financially and her work, while always benefitting from a significant and fiercely loyal following, appeared somewhat at odds with the fashion zeitgeist – the rise and rise of Italian fashion and of minimalism, from Helmut Lang to Prada.

“Andreas made the collections seem more organised and comprehensive,” Suzy Menkes says, “and I felt that he brought in another strand: what 20 years ago was called ‘unisex’ or ‘gender-bending’ but now is considered ‘gender neutral’. The loyalty and energy of Andreas must have done a great deal to guide Vivienne through a period when the Italians came to the forefront, with Armani, Versace, Tom Ford at Gucci, and Prada. I’m sure he both supported Vivienne and worked with her. But it was inevitable – as with relationships like Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé and Valentino with Giancarlo Giammetti – that Andreas was put in a supporting, not a starring role.”

“Vivienne is the only person I listen to… She’ll ask, ‘Is it something you believe in? Or you think is a bit diff erent? Is it something that hasn’t really been seen that way before? Does it follow your instincts? Your beliefs?’” – Andreas Kronthaler

That is true, and while those outside their inner circle may have been unaware of his presence until relatively recently, this is no longer the case.

Still, “Vivienne is the only person I listen to,” her husband says. “She’ll ask, ‘Is it something you believe in? Or you think is a bit different? Is it something that hasn’t really been seen that way before? Does it follow your instincts? Your beliefs?’”

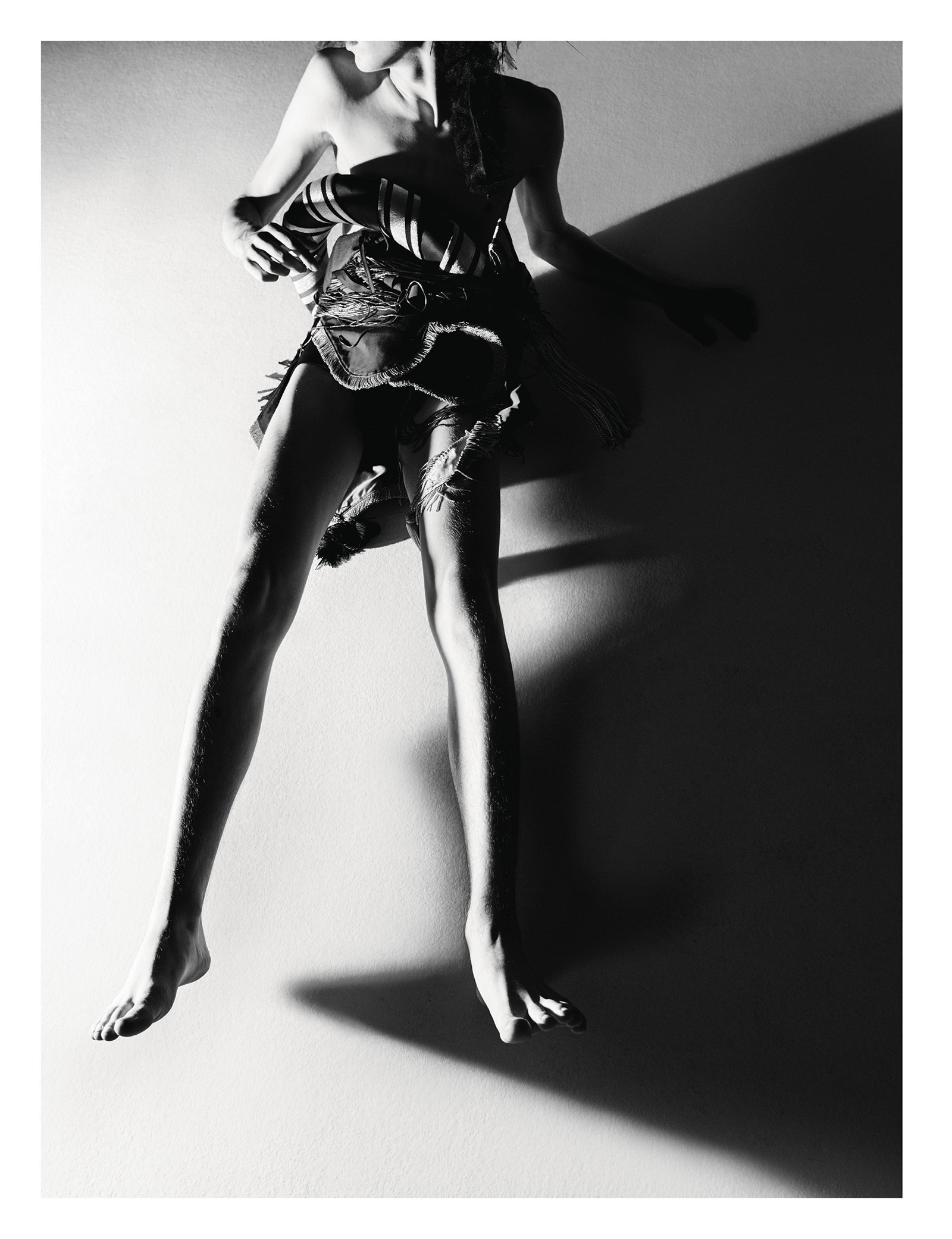

“I’ve always been an anchor for him,” she continues. “Like the corset, for example, is an anchor. It’s something to pin him down. One of the first things he did for me was to send trains down the catwalk, great big dresses. And that’s because this corset of mine, this ‘Stature of Liberty’, you could put anything on it and it looked light as air because it held it to your body. It wasn’t hanging off your shoulders or anything. The 18th-century corset, which I love, was made for boy children at first, to give them posture, and I think it’s lovely. A little girl with no breasts at all, or a woman with no breasts, can wear it and it just tells you: ‘This is my body. This is who I am.’ And Andreas immediately found this usefulness for the corset, the ability to build anything on it. He designed with me, and on that corset. He developed what I’d already done.”

Westwood and Kronthaler cycle to their offices in tandem every day – their bikes have weathered his and hers shearling covers on the saddles – and work on the top floor, where they discuss everything from the story behind a forthcoming collection to the cut and drape of a dress. He is responsible for his own collection, but also for casting more broadly. “Well, he’s just good at it and it takes the burden off me,” she says. “I just like everybody and can’t decide.” For her part, Westwood is increasingly interested in the management of the business and, currently, in simplifying her company structure and encouraging people to “buy less, choose well”.

“It’s an interesting contradiction,” says Philip Treacy, who makes hats for many of her company’s private clients. “When you work in an industry that is partly about superficial consumption, you end up not wanting that fill-in-the-blanks handbag. Vivienne is one of the rare designers in the world – and this is even more powerful today than it’s ever been – who has a singular handwriting. She has a way of cutting, a way of colouring, a way of expressing her creativity in a very singular, particular way. Only she does it like that. Vivienne’s at the top because she’s a different kind of designer – somebody who has been hugely influential. The whole world loves Vivienne’s clothes. We meet people from every culture and Vivienne has made them the ultimate dress for the ultimate moment in their life, a party or a wedding or whatever.”

“I know it sounds silly,” Tracey Emin says, “but when we were younger we had to save up to buy something and then, when it went out of fashion, we would alter it till it came in fashion again. If I bought a jacket, I loved that jacket. I wore it till it had holes in it. I wouldn’t just toss it away and buy something else. It’s about respect, not just for the culture of clothing or fashion, but also the amount of time it took me to save up. So that’s what Vivienne is talking about – not wasting funds, means, energy… All the green issues that go with that. I think Vivienne has made a massive impact on people of a much younger generation, and that’s the generation that is going to be in the position to change things in the future.”

“Right from the start, Vivienne was didactic,” Suzy Menkes explains. “She became very involved in global warming and has supported causes like saving the rainforest, putting notices about it on our show seats along with the fashion programmes. But she really is engaged in the various issues, especially about the effect of our mistreatment of the planet. I admire her for being so resolute. I am absolutely convinced that she cares deeply, that her concern is a genuine part of her character. Vivienne does not change course. She is a true believer.”

“Well that’s me, always trying to protect the underdog,” Vivienne Westwood says about everything she has ever done, from punk to Active Resistance to Propaganda. Referencing “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” – the motto of the French Revolution – she explains: “What the green economy does is give you liberty, which is freedom or control over your own life. What you earn, you keep. You’re not taxed on what you earn. The people who are taxed are people like Rupert Murdoch, who have the airwaves for free, and the people who obviously exploit the land. Fraternity is community. Once you get the land back for your own use, instead of all being on the housing ladder – every man for himself, everybody at each other’s throats – you get community, people helping each other. So this is the fraternity. And equality is equal distribution of wealth and opportunity. That’s what a green economy means.”

Given the location, in the end the subject moves back to Westwood and Kronthaler’s interest in fine art. “When Andreas likes a painting, he might talk to me about it later. And when he does, it’s absolutely incredible,” Vivienne Westwood tells me. “What he says, only he could say. He just sees something that is so essential and so crucial and amazing in things. And because he’s German-speaking, his English – he might say it’s a little bit awful – but it’s actually not, it’s much more poetic.

“Once you get the land back for your own use, instead of all being on the housing ladder – every man for himself, everybody at each other’s throats – you get community, people helping each other. So this is the fraternity” – Vivienne Westwood

“I always ask people, ‘Before you leave the gallery, if it was on fire, what would you choose?’” She pauses for thought before answering her own question. If the Wallace Collection was on fire, which paintings would Vivienne Westwood choose?

“The Laughing Cavalier by Frans Hals, Fragonard’s The Swing. Then I would choose another one of the 18th-century paintings – Watteau. It has to be Watteau. I don’t know which one it would be. They’re all perfect. It’s because they’re so true to life. It’s never self-conscious. There’s this little girl and there’s this dog and everybody’s sitting down. If anyone else had painted that, it would have been self-conscious. It’s his fête galante, the whole idea that gave the 18th century the sense of itself. After this was painted, this is how they saw themselves.”

Vivienne Westwood’s love of life, of the world she and her husband have created, seems, at this point, more magical than ever.

Her husband chooses differently – a piece of furniture, not a painting.

“Before you arrived I was looking at the [André-Charles] Boulle just next to us here. For some reason I was looking at it today having not seen it for years. Anyway, there’s a big wardrobe he made. I’d take that. It’s hilarious because it’s so crazy, the time it must have taken to make it, and then, in the middle of this wardrobe is this clock. It’s unbelievable. I’ve never really questioned it but today I thought, ‘Why is there a clock in the middle of this thing?’” Then, and as matter-of-fact as it is possible to imagine, all while basking in the joy of their world, he realises, “It’s about clothes. It’s about vanity and then there’s this clock. And then I thought, ‘Every time you open the wardrobe you get out a dress and you make the most of it.’ Because, you know, tomorrow, it might all be over.”

Additional interviews by Sophie Bew. Kate Moss interviewed by Olivia Singer.

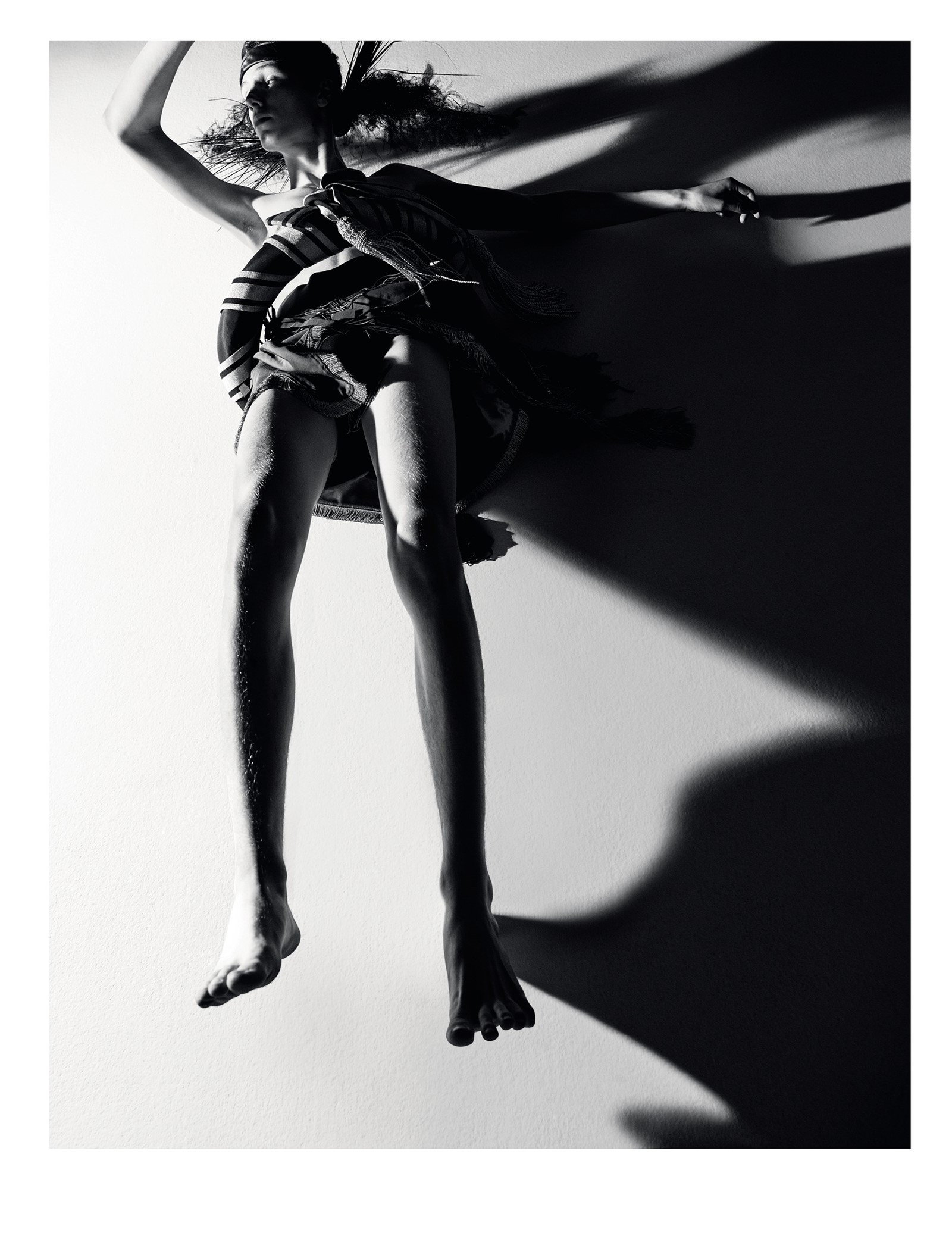

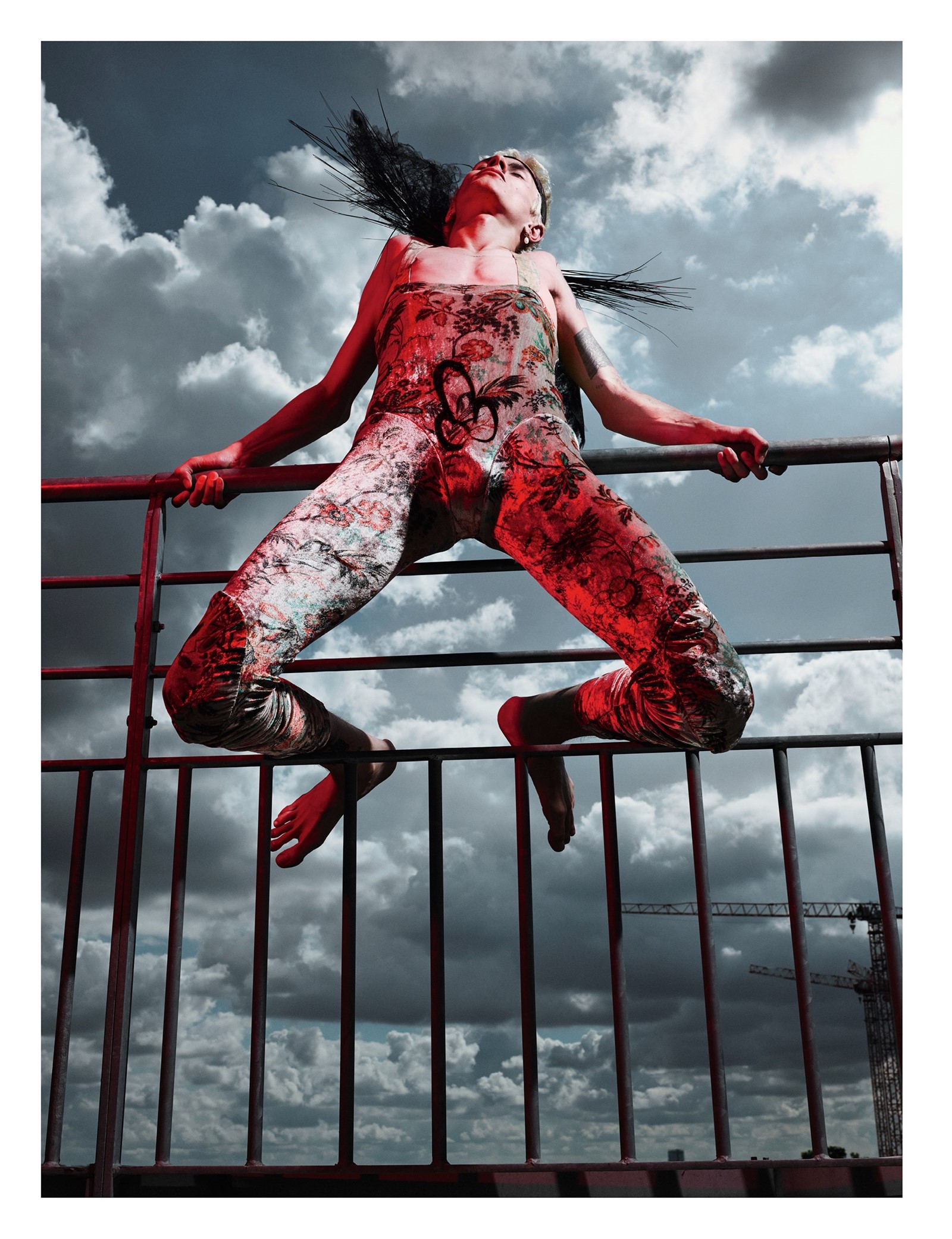

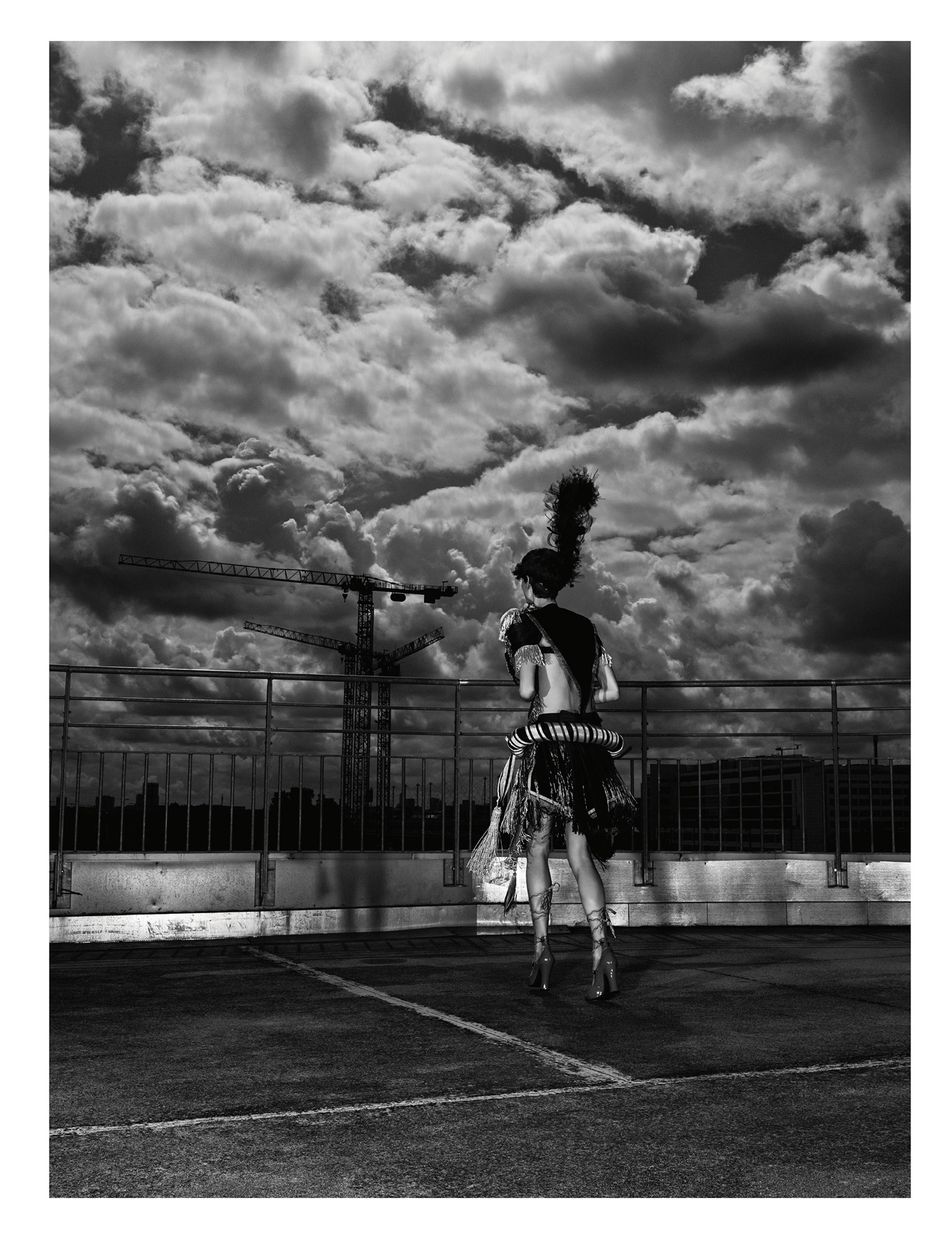

Hair: Tina Outen at Streeters. Make-up: Thomas De Kluyver at Art Partner. Model: Saskia De Brauw at Viva Paris; Daan Duez at Rebel Management; Henry Kitcher at Tomorrow is Another Day; and Joseph Signoret at Success Models. Manicure: Typhanie Kersual. Digital tech: Henri Coutant. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Photographic assistants: Corentin Thevenet and Mikael Bambi. Styling assistants: Niccolo Torelli, Hamish Wirgman and Sinead Allen. Seamstress: Laetitia Raiteux. Hair assistants: Claire Moore and Brendan O’Sullivan. Make-up assistant: Joel Babicci. Studio manager: Charlotte Arts. Executive producer: Jill Caytan at PRODN Paris. Production assistants: Blanche Stagnara, Iris Laverdant and Jade Hill at PRODN Paris. PA production: Yuk Kaij A Kamb. Location manager: Adrien Dournel.

The Autumn/Winter 2017 issue of AnOther Magazine is on sale now.