The 1960s masterpiece offers tutorials in everything from timeless styling to the hazards of heartbreak

When asked if there was a relation between his roles as a poet and a filmmaker, in what would be his final interview in 1975, the Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini confessed “there is a profound unity between the two [roles]. It’s as if I were a bilingual writer.” Never one to shy away from controversy, Pasolini’s visual poetry can be seen most clearly in his film Teorema. A film of few words but overflowing with arresting visuals, its debut rocked the cultural world in 1968, as it won awards at the Venice Film Festival while simultaneously facing criticism from the Vatican.

The fable-like tale follows a middle-class bourgeois family in Milan seduced by a mysterious visitor, played by the dashingly youthful Terence Stamp. In the relaxed Italian sunshine every member of the family falls for Stamp’s tight-trousered character. Awakened by their sexual encounters, the conventional family falls into disarray on his departure. The head of the household, a wealthy factory owner, strips himself of all his possessions – including his clothes – before running away from the comfort of his own empire. The maid returns to her hometown to perform miracles, and the mother, played by the captivating Silvana Mangano, is sent down a slippery slope of desire that sees her driving around backstreets picking up young men who resemble the visitor in an attempt to recreate the time they shared together. Here, we take a closer look at Pasolini’s surreal society and take note of his own sprezzatura (or studied carelessness) and the other style lessons to be learned from the auteur's first professional cast.

1. Style doesn’t age

The film famously features the designs of Roberto Capucci who revealed in an interview with the Italian magazine L’Unità in 1994 that Pasolini had specifically instructed that “the characters should not be dressed too fashionably so that 20 to 30 years later the film would not appear too dated”. Pasolini’s wish has been granted, as relaxed chiffon, peter-pan collared dresses, white woollen knits and camel coloured chinos comprise a wardrobe we’d happily wear today. It’s a welcome reminder that sometimes it’s good to resist trends and the temptation of jumping on the fast-fashion wagon: investment pieces stand the test of time.

2. Know the power of a palette

Another note that Capucci made was Pasolini’s insistence on dressing the mother Lucia “in pale hues” at the start of the film and “only put some colour into her clothes at the end when she discovered love”. Watching the subtle shades transform throughout the film as it moves from sepia news-cuts to elegant tableaus of blush pinks it’s evident that Capucci followed through. In his own words, the visuals shade from “beige and sandy colours at the start, then at the end coral red.” This final deepest shade comes in the form of an elegant skirt-suit worn by Mangano with matching lips, a true transformation from her beginnings in the purity of a white two-piece. Follow Capucci’s example and use colour sparingly for real impact.

3. Master the cat eye

Never underestimate the power of a statement look. Although the fashion of the film resists trends, its make-up embraces the 60s affection for a graphic cat eye. With liquid liner invented in the 50s, it’s no wonder the iconic flick is used to focus us on Mangano’s gaze in every scene. While everything else changes, this stylish mask remains a constant, an identity that her character Lucia is able to reaffirm daily at her dressing table as the security of her once simple bourgeois world collapses. Make-up covers all manner of sins but it can also comfort and enhance one’s sense of self. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, why not follow Lucia’s example and give them wings?

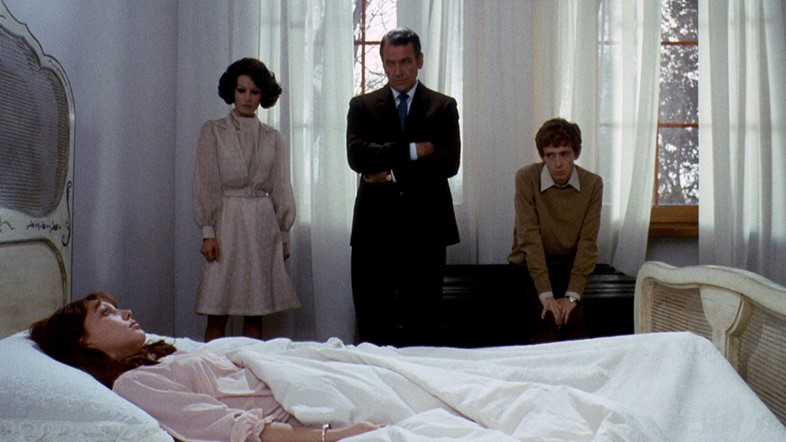

4. Don’t dwell on the past

Recording memories can be a powerful and pleasurable activity. Yet the family’s daughter Odetta finds she is unable to shake off her recollections of the past after her sexual encounter with the visitor. Rather than looking forward to her future, she immerses herself in photographs where she’s able to look back in detail and even physically trace with her finger the lines of the body she misses. Unfortunately the vividness of the memory causes her to be struck down with grief. In bed she becomes catatonic, her fists clenched and quivering. A modern sleeping beauty, lying in a rose-pink nightie with frilled lace, she stares dead-eyed at the ceiling, a healthy reminder that dwelling on the past is rarely productive. Focus on the future. Don’t look back and idealise old relationships (we’re looking at you, social media addicts), instead look ahead to what’s next.

5. Channel your emotions to positive effect

It’s no secret that strong emotions fuel creativity. Unlike his sister, the son of the family Pietro – pours his grief into creative projects. Art becomes a great release and distraction from the emotional upset caused by the stranger’s sudden departure. His memories of their encounter manifest in colour: “Blue reminds me of him”. A blue period begins for the budding artist, a blue that stems from Stamp’s blue eyes, his own blue knitwear and the blue jeans donned as the two looked at the works of Francis Bacon together. Memories can be painful, but as Pietro proves, put to good use they can create beauty.