They say never meet your heroes, but what about your Heroines? Opening the first page of Kate Zambreno’s 2011 book one summer, I was greeted with the dedication “for the girls who seem, as they did in Virginia Woolf's time, so fearfully depressed”; with that, I had found a philosopher who could write the world as my generation saw it, forwarding a new kind of feminism. Heroines felt like a clarion call for an alternative canon, giving new agency to the Tumblr girls, the self-conscious girls, and the girls who write and rewrite themselves every day, in some way or another. Across non-fiction, essays and fiction (Green Girl, O Fallen Angel), perhaps no writer working today understands so accurately how a girl’s selfhood is constantly sticking to someone else’s story: to other women, consumed and collected from films and books. Like Sofia Coppola, or Louise Bourgeois, the world Zambreno creates is so much to do with herself, as well as all of us.

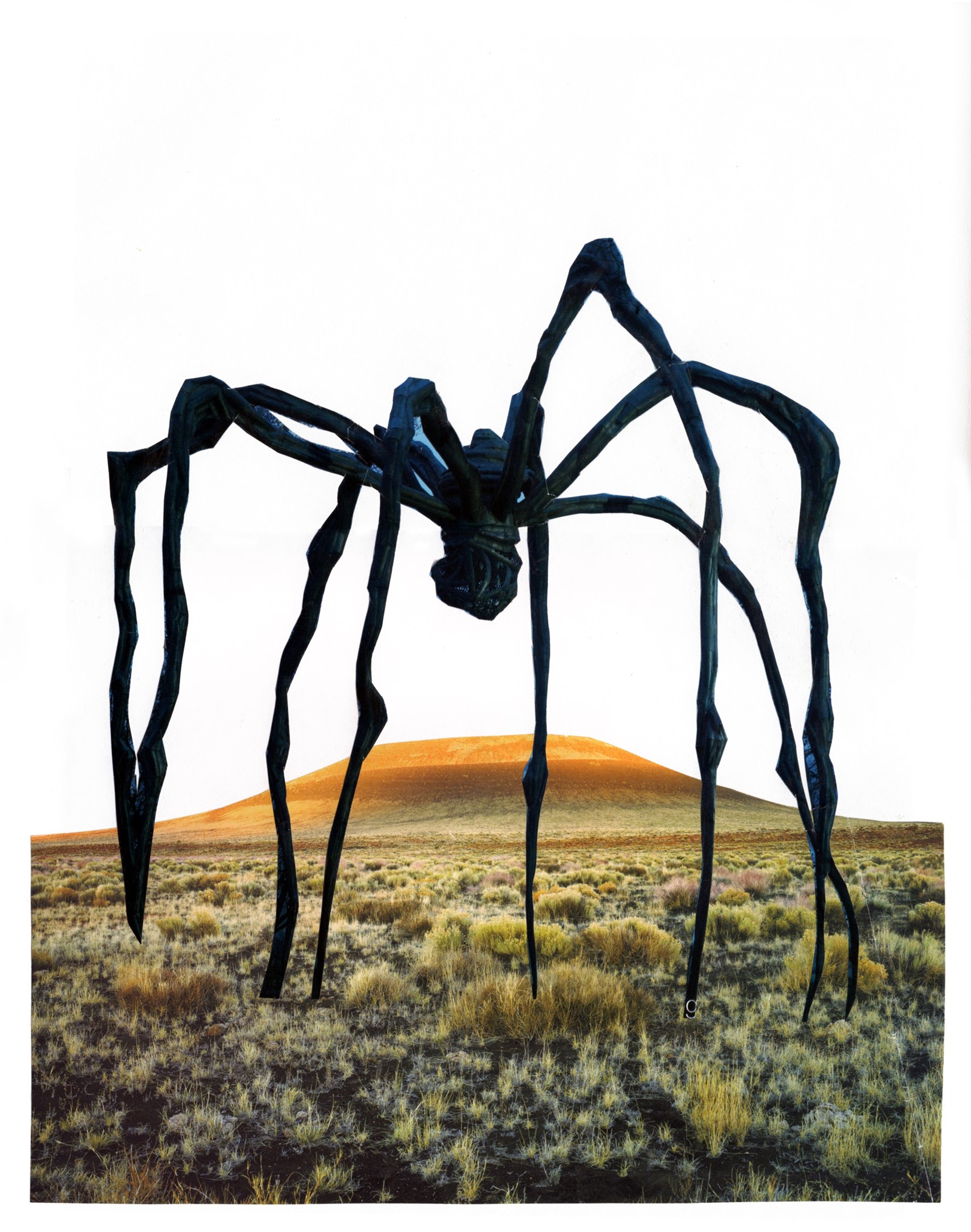

Now, with Book of Mutter, Zambreno is bringing her already subjective take on criticism into freshly personal territory. Composed over a 13 year period, the elegiac work combines essay, memoir and poetry to explore Zambreno’s process of mourning after her mother’s death from cancer. Through meditations on photography, clothing, and the daily routines of women’s lives, Zambreno pays tribute to her mother, unpicking her own relationship with her as well as confronting the secrets of her life. Louise Bourgeois plays a part – the structure of the book, designed to feel like “living through a series of rooms of memory”, deliberately echoes the artists’ Cells – as does Virginia Woolf, and controversial outsider artist Henry Darger. But the magnetising centre is Zambreno’s mother, who remains hard-to-capture, elusive. This ultimate unknowability, haunting all of us who lose someone close, is reflected in the restrained use of images and deliberate gaps, which lend the book an overwhelming sense of things left unsaid.

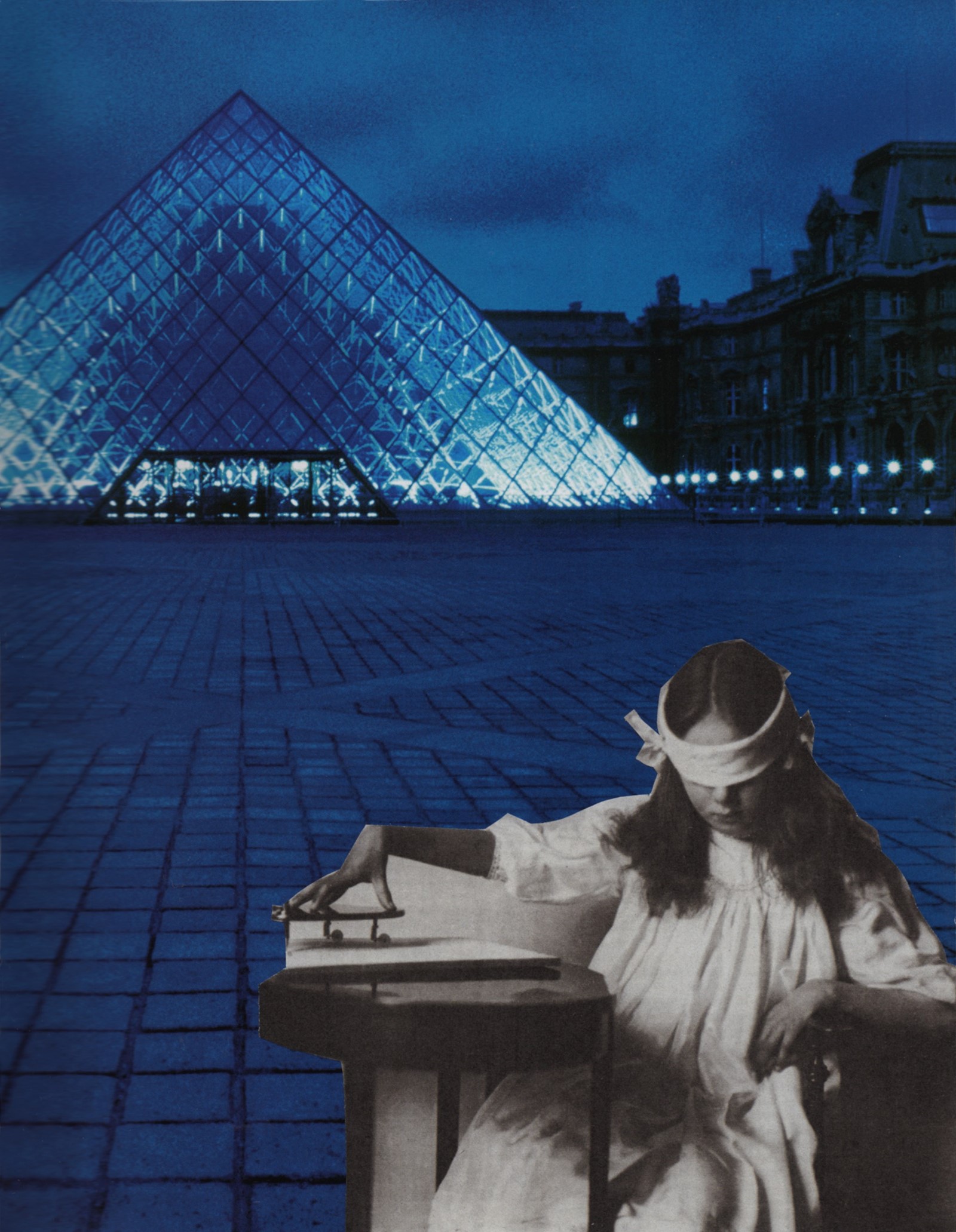

In the spirit of his memorable cover design for Heroines, Semiotext(e) editor Hedi El Kholti contributed some original collages to accompany mine and Kate’s conversation here – images which, from Renee Falconetti’s Joan of Arc to Rosemary’s Baby, respond to the world of references that didn’t make it into the book, as well as those that did. Unlike the opening of Heroines, Book of Mutter’s dedication doesn’t attempt to address the imagined reader, reading, simply, “For my mother”. “It’s a very blank dedication,” Zambreno admits, speaking to me on the phone from New York one Saturday morning in April. “But there’s a lot behind it.”

Claire Marie Healy: How did you come to write Book of Mutter? Is where you ended up anywhere near how you first envisioned it?

Kate Zambreno: When I started working on the book 13 years ago, it was pretty much parallel to when I started trying to write books at all. I try to work on many books at the same time, and they wind up taking a long time because of that. I work really well with (that) sort of chaos. But it came out of this intense feeling of mourning. I knew that I needed to write something about it, and I knew that the writing would be fractured and non-linear, and deal with different forms, and deal with ways that I read. For a while – and I think this is why Henry Darger and Louise Bourgeois are so pivotal in the text, in terms of both of their projects – I had no idea what form it would take. Book of Mutter was like, my whale. The thing that hung around my neck. For so long, I just wanted to get rid of it, but then I couldn’t, and it became very ritualistic. Every year, often during the anniversary [of her mother’s death], out of a sense of this inner compulsion I would begin working on it again. I wanted it to be [like] living through a series of rooms of memory, circling obsessively over this one thing. Ultimately, the book became about the processes of writing a book, and how writing a book can also be a form of mourning.

“Ultimately, the book became about the processes of writing a book, and how writing a book can also be a form of mourning” – Kate Zambreno

Your previous writing has had this interplay with a kind of struggle to write. In what sense is the process of writing almost mirrored in the process of grieving a loved one?

It’s interesting to me, that question of writing as mirroring grief, and how grief can come up again. [Recently] I went back and re-read Barthes’ Mourning Diary. And I felt it so deeply, this idea that he advances, that grief is non-linear, that it’s chaotic, and that it’s discontinuous, [as well as] the impossibility of writing it, but the need to. I’ve been doing this rather masochistic project, which is not what I’m supposed to be working on. It’s called The Appendix, and it’s a series of talks and essays about Book of Mutter – kind of what I didn’t do or what continues, [exploring] the notion of a text as ongoing. The first talk dealt with how I finished Book of Mutter, in its final form, after I had this intense desire to work on the text, not the previous February but the February before. The strange thing is I became completely consumed with it, working on it for 12-hour days for a month, when I had refused to look at it for a while. And I found out at the end of it that I was pregnant. I don’t interpret it to any kind of mystical connection, I think it was hormones, hormones doing something good as opposed to something bad, where I just had a lot of energy.

And do you have a little girl or a little boy?

I have a little girl. When I found out, I almost felt a sense of grief over that. She will be whoever she wants to be, and express herself in whatever way she wants to, but just the idea of a daughter felt too much. The circle of what I was thinking through. But it’s really uncanny, of course, to look at her and think of my mother looking at me, but it’s beautiful too. It’s intensely beautiful and painful at the same time.

Something that does come across in the book is the uniqueness of that relationship between a mother and a daughter.

I write just as much about mourning sons in Book of Mutter – certainly Roland Barthes, Peter Handke, and Henry Darger. But [when it comes to] the mother daughter role, there’s a devouringness, and a claustrophobia, and also this really intense sense of a mirror, especially within the notion of traditional femininity. The mothers and sons I write about in Book of Mutter are almost romanticised, but the mothers and daughters I write about, [like] Marguerite Duras’ The Lover, Elfriede Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher, [and] Violette Leduc’s The Bastard – these are much more violent and devouring relationships.

“Louise Bourgeois was a huge inspiration – how can a paragraph be a cell, how can writing be filled with objects?” – Kate Zambreno

Those fraught mother-daughter relationships remind me of Lenù’s relationship with her mother in Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan Novels – this very physical, violent fear she has of becoming her mother, reified in her phantom limp.

I’m afraid to read Ferrante. I’ve read The Days of Abandonment, which of course I loved. But since my father’s side of the family is part Neapolitan, I think it’s too close for me! It seems so much like depictions of my father’s side of the family, and of course also my mother, like this intensity and this devouringness – I can’t read it. I think a lot of people see their family relationships mirrored in her, but for me, it’s just like, that reminds me of my family!

Obviously photography in many forms is important to Book of Mutter, but you only display actual photographs three times. What was behind the decision to not reveal the images referred to, like the family photos, and to describe the visual rather than display it?

I’m really interested how Roland Barthes writes of the winter garden photograph in Camera Lucida. He says he can’t show the image because, when he looks at the image of his [late] mother when she’s five, this discovered image is still wounding for him. If he were to reproduce it in the text, it would not be wounding for the reader, and so he chooses to describe the image as opposed to showing it. That’s partially the spirit of why I describe so many of these childhood photographs in Book of Mutter. Because to show it would be just illustrative, but to describe it, it’s about what the limitations of language are, how language can become its own object, how it can be sculpted. Louise Bourgeois was a huge inspiration – how can a paragraph be a cell, how can writing be filled with objects? How would just showing a photograph just be illustrative, and doesn’t get at the ghostliness of what is not seen? And that’s what I wanted to have, that sense of absence, that sense that we can’t see the image.

That said, at one point you do show an image of your mother – the found image of her standing in front of a car, paired with an image of Wanda standing in front of the courthouse, in Barbara Loden’s 1970 film of the same name. Why?

My friend, the writer Sheila Heti, read Book of Mutter, and wrote me – I don’t think she realised it was already at the printer! – “You must not use this photograph of your mother. You can’t use it, because when I was reading it, I kept on thinking in my mind, ‘What [did] your mother look like?’, and I didn’t want to see what she looked like.” But it’s not an image of her as I knew her, it’s this mystery. For me this image looked like it was a film still. And I found it incredibly uncanny how similar the image was to a still from Barbara Loden’s Wanda, which is a continuing obsession of mine. And I realised that I always saw Wanda, and Barbara Loden as a surrogate, as a sort of blank character who is not seen as having an identity outside of men. [I’m] thinking of my mother as a film still, my mother as this interiority that I still cannot grasp because she’s gone, and my mother as an actress of sorts.

Diary-writing comes up more than once in the book – Henry Darger’s obsessive weather journals, for instance. How does notebooking contribute to your writing process?

For me, my notebooks are this elaborate practice for future works, and all the works do, at some point, seed out of the notebooks. I have little notebooks, I have a diary, a reading notebook... I have a notebook of notebooks! [They] are where I put my reading, which is where I put my thinking, or where I put my seeing – after I see something, or observe patterns and rituals. It is autobiographical, but it’s [also] like a poetic practice for me, how I try to think of how the work can have that dailiness. A tremendous amount of Heroines came out of my notebook, originally, but after years of working it over and over, Book of Mutter is less of a diary for me – there’s so much less of the noise of the everyday. But in new work I am continuing to think seriously through the day, how to write the day. How can writing be about the ongoingness of time?

Among those descriptions of her daily life, I found the references to your mother’s clothes and make-up among the book’s most affecting. Like the row of Clinique lipsticks she left behind, or the black skirt of hers that you try and wear even though it doesn’t fit.

A lot of stuff about clothing was taken out of Book of Mutter, just because I had too many threads – no pun intended. I think that there’s a lot of shame in the writing world, that women are not supposed to be excessive or care about clothes. Semiotext(e) had an event, a big dinner in New York and Michèle Lamy was there. I have never been star-struck like this in my entire life. I was shaking. I went up to her and told her how much I loved her. Everyone who I talked to there were these writers and interesting people, and all I could talk about was the fact that Michèle Lamy there, and no one knew who she was. I was like, how could people not know everything about her. Do you know she studied under Deleuze?

Amazing!

I wanted to just kneel at her feet. I was completely weird.

There does seem to be this shame around female authors writing about fashion, which does a disservice to the meaning-making of the clothes we wear. What continues to draw you to writing about clothing nonetheless?

There’s something about the worn clothes of someone, about clothes as witness to a life. In Heroines I talk about this Hussein Chalayan turtleneck that I’ve had for 15 years. It has sweat stains on it, and I love the sweat stains intimately. But when Heroines came out, someone interpreted it that I was obsessed with glamour. When I think of glamour, I think of something rigid and hard and about perfection. But [for me] its not only about the fact that I think of Rei Kawakubo as an artist, or that I’m obsessed with various garments and I love amazingly designed pieces, as artwork. I love this idea of what we wear, the fact that I’m still wearing the same cream robe every time I write, that sort of warmth, and smelliness in these objects. I wrote an essay on Kathy Acker for an anthology, and I was speaking to [her executor] Matias Viegener. Of course she was obsessed with Comme des Garçons, but also he said, and I always think about this, that when he thinks of her clothes, he thinks of her sweatpants. She loved leisurewear. There’s something there, I don't know what it is. Tenderness? But those things seem to repeat in everything I work on…

Book of Mutter by Kate Zambreno is out now, published by Semiotext(e).