We select our top picks from Fondazione Prada’s new film festival, a recreation of the groundbreaking New American Cinema Group Exposition held in 1960s Turin

Fondazione Prada is dedicated to educating modern audiences about Italy and Europe’s cultural heritage, particularly in regard to experimental art forms. In 2013 its artistic director, renowned art historian and curator Germano Celant, masterminded the reconstruction of revolutionary show Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form, curated by Harald Szeemann at the Bern Kunsthalle in 1969. For the foundation’s latest project, the focus has shifted to film, Celant recreating the New American Cinema Group Exposition, a festival held in Turin in 1967, whereby members of the group of young radical filmmakers, spearheaded by lauded auteur Jonas Mekas, were invited to show a selection of their work.

“I was there at the time,” Celant tells us over the phone from Milan, where the month-long festival is now in full swing. “There was a lot of artistic exchange between Turin and the US in the 1960s. Radical American artists were a bit like refugees. They could be arrested for the controversial nature of their work, and Europe was a place where they could exhibit freely, which is why Turin invited Mekas to curate this collection of films.” The original festival screened 63 films, presented in 13 different programmes, and almost all of these are being screened at the Milan revival, with around 60% of the works having been digitally restored by the foundation.

Mekas and his fellow pioneers, including his brother Adolfas, Stan Brakhage, Robert Breer, Bruce Conner, Marie Menken and Stan VanDerBeek, developed the NACG as a direct reaction to the Hollywood film industry, aligning themselves instead with countercultural literary, theatre and art movements of the time, from the Beat Generation to the Living Theatre to the Fluxus experience. “This is not easy cinema,” Celant explains. “After what is now 50 years of Hollywood movies, this kind of experimentation is very difficult to follow. My god, it’s like seeing a two-hour Kandinsky movie! It’s abstract: there’s no narrative, no story. It’s a fast-paced montage, where many of the filmmakers experimented with the film itself – playing with its surface. And it’s still a radical language today; which is why we felt it was so important to share these films with the world.” Here, we’ve selected seven of the most fascinating works from the festival’s line-up, spanning surreal animated collage assemblage and a psychedelic ode to nature.

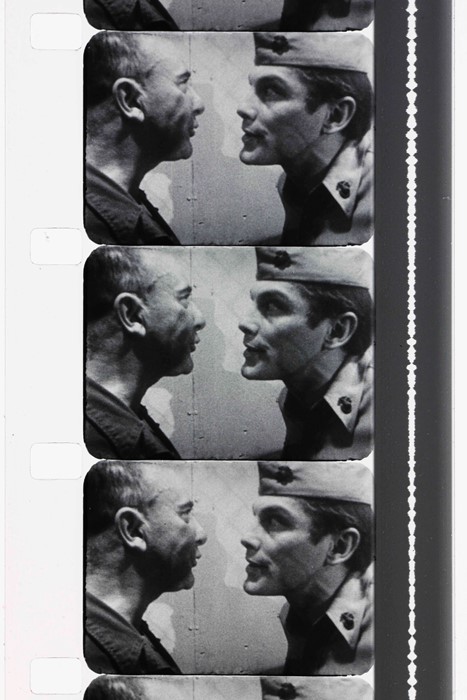

1. The Brig (1964) by Jonas Mekas

In 1964, Jonas Mekas attended the closing night of the Living Theater Company’s off-Broadway play The Brig – a harrowing study of life in a Marine Corps brig (or jail) in 1950s Japan. The stirring, ultra-realistic performance got him thinking: “Suppose this was a real brig [and] I was a newsreel reporter [with] permission from the U.S. Marine Corps to go into one of their brigs and film the goings-on: What a document one could bring to the eyes of humanity!” This idea so inspired the auteur that he walked out half-way through the play, determined to film it in its entirety; to find out what happen next “with my camera”. The result is this captivating, controversial and technically brilliant film, which won best documentary at the Venice Festival, and is, in Mekas’ words, “a record of my eye and my temperament lost in the play”.

2. Melting (1965) by Thom Andersen

Prior to watching Melting, one of the earliest films by influential filmmaker and essayist Thom Anderson, it’s hard to imagine how the gradual melting of an ice-cream sundae could make for compelling and aesthetically pleasing viewing. Anderson’s purpose in making the film was, in his words, to document “the natural, mono-structural disintegration of strawberry ice cream; its passage from rigidity to softness, from edibility to decomposition.” The effect is strangely spell-binding – a thoughtful reflection on evanescence – while the sumptuous colour palette is reminiscent of an Irving Penn still life.

3. Andy Warhol’s Silver Flotations (1966) by Willard Maas

New York filmmaker and poet Willard Maas and his wife and fellow filmmaker Marie Menken were described by Andy Warhol as “the last great Bohemians. They wrote and filmed and drank – their friends called them 'scholarly drunks' – and were involved with all the modern poets.” This four-minute film by Maas is the only visual documentation of Warhol’s celebrated installation of silver helium balloons, shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1966. Jonas Mekas described the dreamy portrait of these drifting silver vessels it as “a film about grace – if such a word exists”: an apt summary of its lyrical charm.

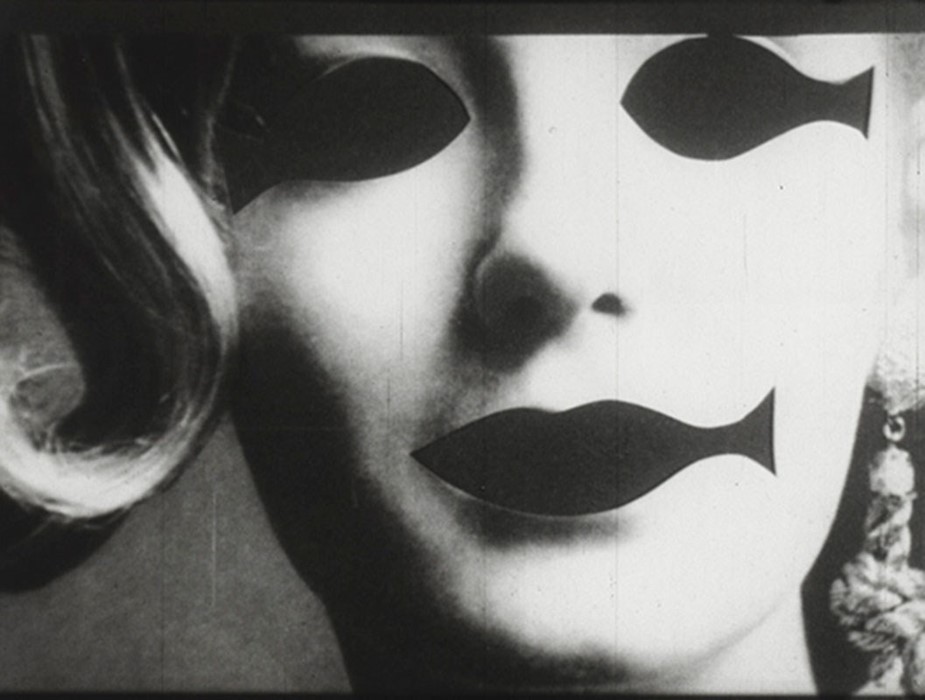

4. Vivian (1964) by Bruce Conner

In the original festival programme, Mekas describes multimedia artist Bruce Conner as a man who “doesn’t like to be taken seriously,” adding, “he even asked me not to write anything about his film, and not to provide any explanation of his work”. This three-minute film, a satirical quip about the sterile nature of the art world, is typical of his humour and wit. It depicts its titular subject, Vivian Kurz, placed on display in a glass case during an exhibition of Conner’s work in San Francisco – a literal demonstration of the ways in which curatorial preciousness can sap the life from an artwork. Conway Twitty’s rock ‘n’ roll ditty Mona Lisa provides an upbeat soundtrack, enhancing the film’s frenetic pace and the absurdity of the environment it’s critiquing.

5. Bridges-go-round (1958) by Shirley Clarke

Before turning to film, Academy Award-winning director Shirley Clarke trained as a dancer and as such approached the medium with an inherent understanding of choreography and rhythm. This early experimental work is a beautiful exploration of New York City bridges, which sees Clarke employ camera panning and superimposition techniques to mesmerising, kaleidoscopic effect. The same four-minute edit is played twice during the film, first set to a jazz score and then to an electronic one, the different genres prompting different observations of the vast, geometric structures. Writer Howard Thompson described the work as “a film that captures the bizarre magic of man-made spans with the movement of a lightning clap and with the same terrible beauty”.

6. Dog Star Man (1961-64) by Stan Brakhage

Stan Brakhage was renowned for his experimentations directly onto film, whereby he would scratch and punch holes into the reel’s surface to create extraordinary abstract imagery. This five-part film, created between 1961 and 1964 and described by Brakhage as his “cosmological epic”, is widely considered his great masterpiece. Notoriously difficult to describe, it follows a bearded woodsman (played by the artist himself) who experiences a number of mystical, psychedelic visions as he clambers up a snowy mountainside to fell a tree. As Hal Erickson critic once put it: “If you're looking for a plot, you've come to the wrong filmmaker. If you're looking for a fascinating mosaic of images combined to ‘interpret’ the creation of the universe, then Dog Star Man will be right up your alley.”

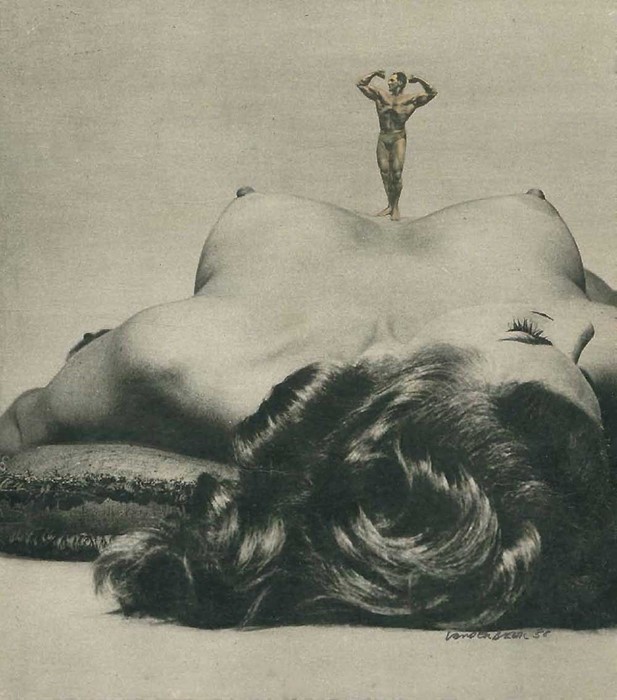

7. A La Mode (1959) by Stan VanDerBeek

Stan VanDerBeek began making his brilliantly surreal illustrated and collaged assemblage films in the 1950s, combining “slick magazine illustrations and animating them… with comic or satiric purpose,” to quote Dick Bergman. His rapidly cut short A La Mode – which sees, among other things, a woman’s chest become an uneven landscape as a small car ventures over its terrain, a pair of heads with arms for bodies busily conversing and various everyday objects emerge from eyes and mouths – is one of his finest works. Vanderbeek branded it “a montage of women and appearances, a fantasy about beauty and the female, a fomage, a mirage. An attire satire.”

The New American Cinema Torino runs until April 30, 2017, at the Fondazione Prada, Milan.