The Caravan Club was a Soho haunt billed as ‘London's Greatest Bohemian Rendezvous’ but closed down after only six weeks. Now, the historical hangout is open to visit once again

When the authorities describe a place as “a sink of iniquity,” surely only the most puritanical amongst us could resist a hankering to visit. That was one of the many accolades bestowed on The Caravan Club in London’s Soho when it first opened in the 1930s as a gay-friendly members club, at a time long before homosexuality was legal.

Then, anything outside of the heteronormative was often communicated through a highly creative series of verbal signifiers and physical gestures: Polari was a comprehensive form of slang adopted by gay people to subtly demonstrate their sexuality (today, we still use “naff”, “zhoosh” – as in zhooshing up your hair, and “slap” for make-up); while certain exaggerated physical gestures hinted at queerness to those in the know. Thanks to suffocating societal and legal curtailments, The Caravan Club had to convey its queer-friendliness using coded language: it was marketed as “London’s Greatest Bohemian Rendezvous, said to be the most unconventional spot in town.”

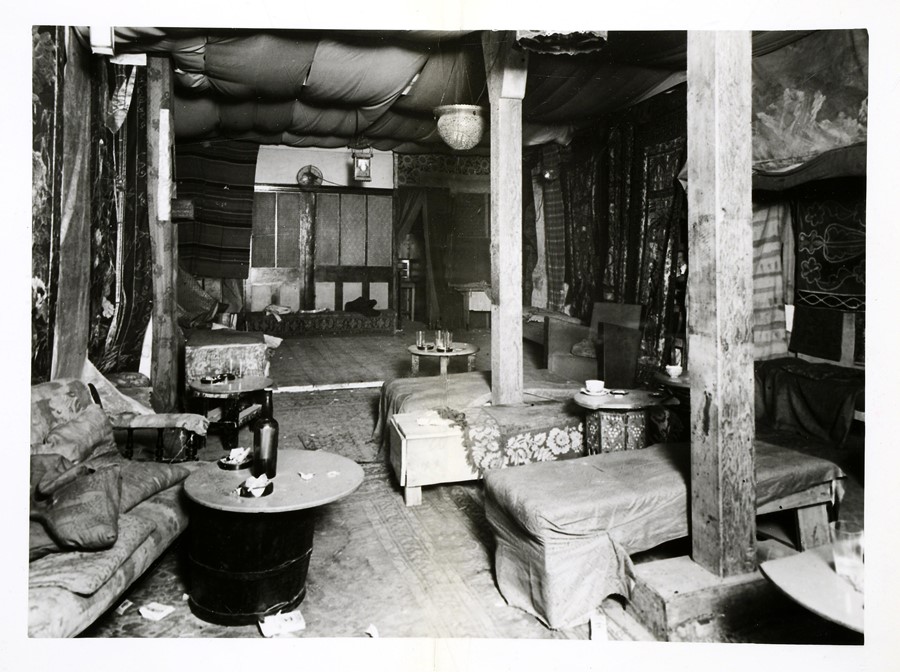

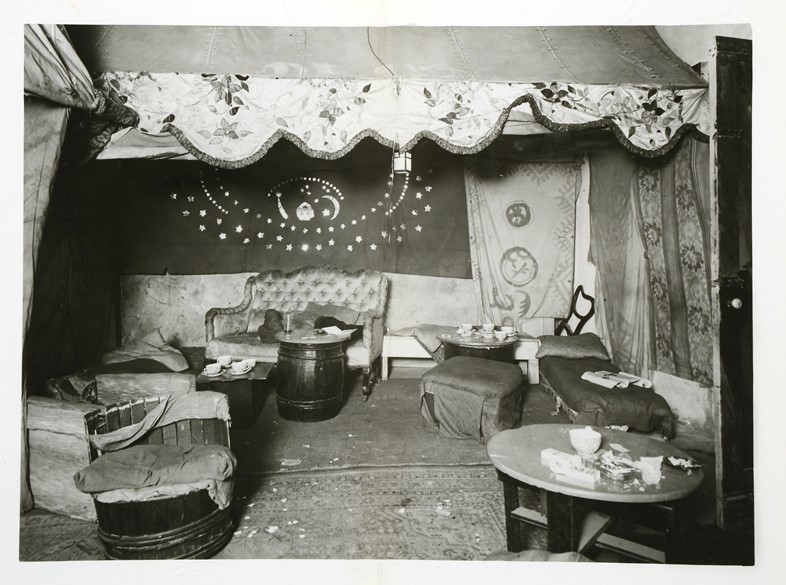

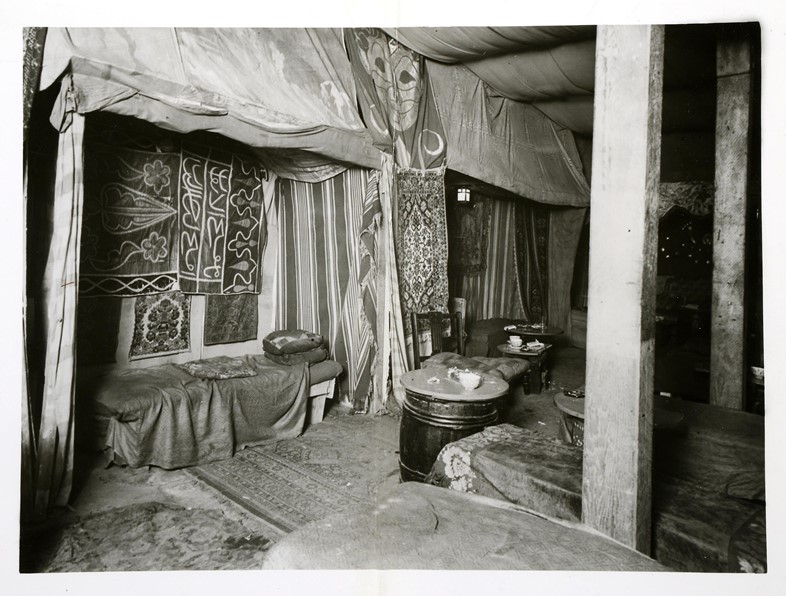

The name of the club was derived from “Caravanserai,” an antiquated term describing “a kind of nomadic community who moved around, pitched their tents and built their village in different places,” explains Joe Watson, London creative director of the National Trust. “It’s a reference to the tent-like interiors and the temporary nature of the club.”

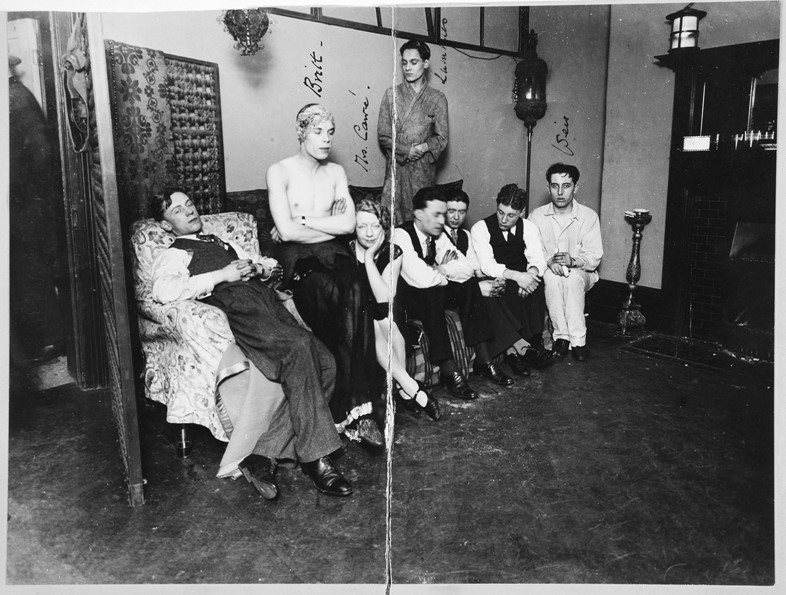

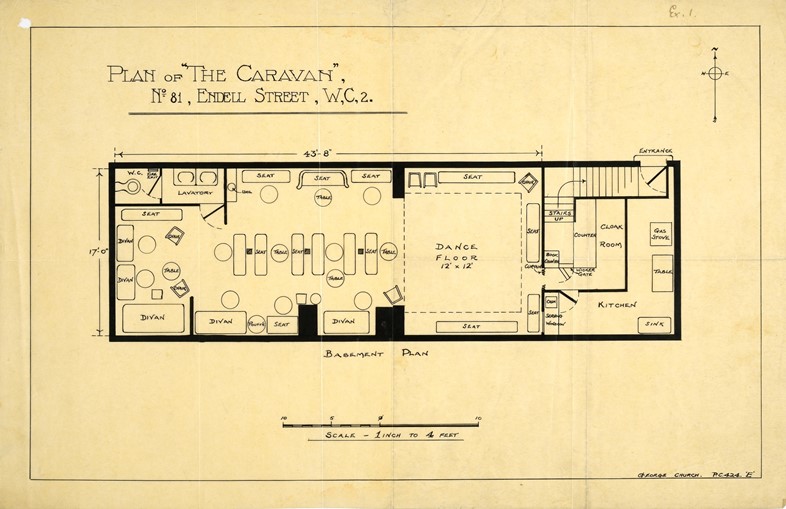

The Caravan opened on July 14, 1934, but closed after only six weeks. In October that year, its founder Jack Neave was sentenced to 20 months’ hard labour after being taken to court along with the club’s funder William (Billy) Joseph Clifford Reynolds, accused of “maintaining a place at Endell street for exhibiting to the view of any person willing to pay for admission lewd and scandalous performances”. 21 others were arrested in the last of many police raids at the venue, accused of “aiding and abetting” the pair. For its short life, the club made a big impact, and provided what sounds to be a wildly fun and most importantly, non-judgmental spot for gay people to dance, drink and enjoy the freedoms their heterosexual contemporaries could without question.

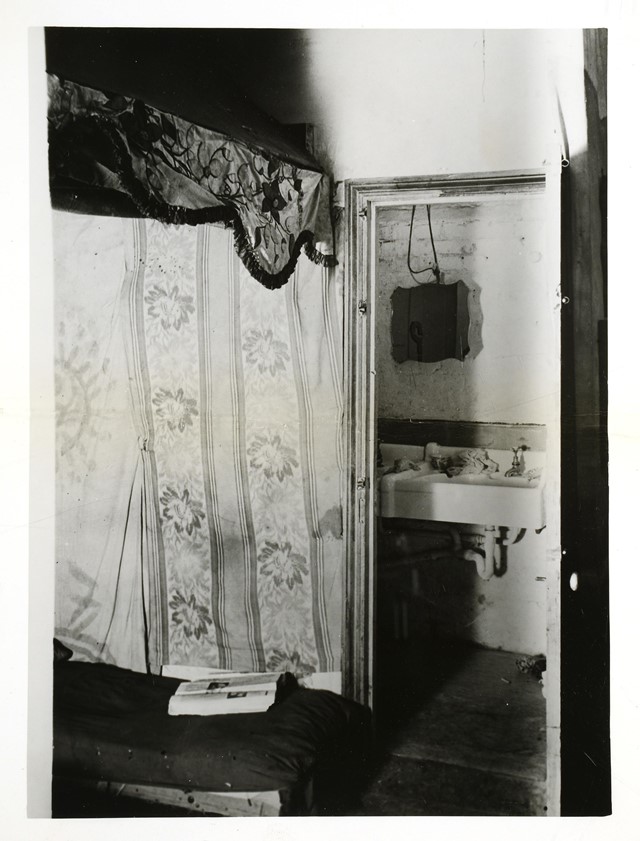

The Caravan Club is now being exhumed by the National Trust, which has reconstructed the venue using police photographs, court reports and witness statements as part of its Queer City project that marks 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales. The Sexual Offences Act was passed in 1967, ruling that “homosexual acts in private between two men” over the age of 21 was now legal (Scotland and Northern Ireland followed in 1980 and 1982 respectively).

“We really wanted to inject the human element into this story,” says Watson. “In The Caravan Club we know details like a torn-up love letter that was scooped up by the police and then used as evidence in court; and a quote from a person who didn’t know they were queer until they moved to London. That sort of connection between the city and queer identity felt like a really important thing to explore.”

Located on the cusp of Covent Garden, the 2017 version of the Caravan Club is almost at the exact spot of its original incarnation on Endell Street. Walking into the space feels magical: the interiors are swathed in coloured fabrics with a multitude of patterns, hung from the ceiling, draped across furniture, covering the floors and haphazardly strewn across the barrels that form makeshift tables. It’s like the languid aftermath of a decadent bohemian afterparty: the divans are deserted but hint at wild scenes, twee china cups and saucers bear the dregs of the whisky being drunk from them the night before. The lighting and the materials are soft and exotic, but even as a recreation everything is suffused with enigmatic sexuality.

Perhaps it was the transient nature of these spaces that enabled for such a potent distillation of this sort of liberated energy. Clubs like Caravan were founded in full knowledge that they would soon be closed down: “There’s a very strong sense of the resilience of that community, and the necessity for creating space in which they could operate,” says Watson. The owners and patrons simply moved on to somewhere new, navigating the city’s hidden queer spaces through euphemisms, codes, and word of mouth.

Clubs weren’t just important to the gay community as a place to drink, dance, flirt and have fun – as semi-public places they provided a refuge when even at home many people couldn’t be open about their sexuality. “At that time the gay community was identifying places or spaces and negotiating where they could be themselves,” says Watson. “Sometimes it’s in public spaces, but not in public ways – it feeds into longer narratives around cottaging or using public spaces for sex. It’s a very important and somewhat sidelined history we’re trying to tell here.”

It’s a vital story indeed, and one that underscores the significance of clubs that offer a safe space to the LGBTQ+ community. Although gay and trans people today have the same rights as hetero-folk, that’s not to say society is totally free from prejudice and discrimination. Dedicated queer spaces offer both a physical and metaphorical refuge and engender a freedom that even the 21st century outside world might not. In a climate where recent years have seen the closure of countless gay clubs and bars – among them Hackney’s The Joiner’s Arms, Soho’s lesbian Candy Bar and drag bar The Black Cap in Camden – recognition of these spaces’ importance both as part of a historical narrative and of an inclusive, liberated contemporary society is vital. “While any measure of prejudice or discrimination exists, those places are going to play a very important role,” says Watson. “They’re part of the creative engine of the city, and hopefully long may that continue.”

The National Trust’s recreation of The Caravan Club is open from March 2 – 26, 2017, in London.