Inspired by the Olympics, we champion the lesser-known athletic pursuits of Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso and Frank Stella

The notion that art and sport lay in opposition is not unusual – the painter’s inward directive contrasts with the outward nature of the strike of a baseball bat, for example – but the two are, historically, intrinsically linked. Take Edgar Degas’ renowned painting The Dance Class, and the fascination with dance that preceded it, or Jack Kerouac’s college football career, albeit short-lived, which provided plenty of inspiration for future works. Below, we look at three artists whose engagement with the sporting world was at once significant, and influential.

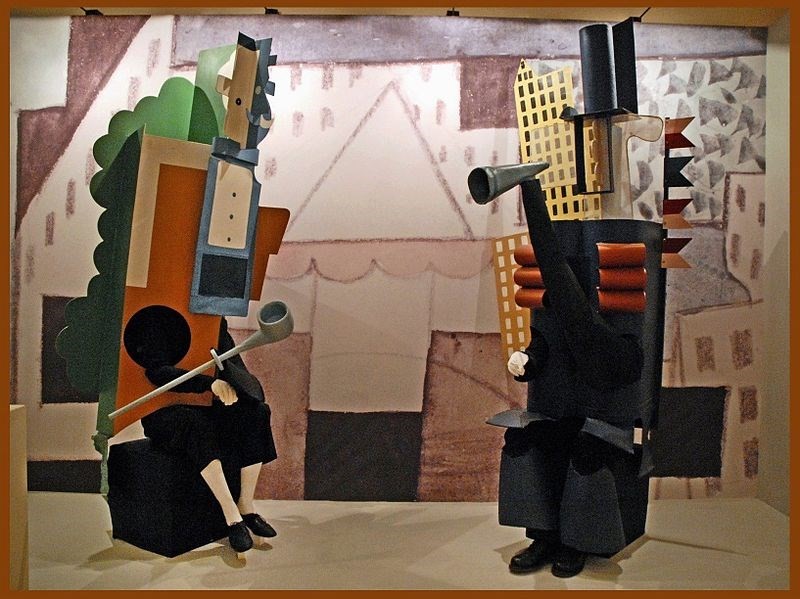

Pablo Picasso on the Ballet Russes (above)

At the height of his career Picasso sidetracked from his customary practice of paintbrush on canvas, undertaking set and costume designs for a number of the Ballet Russes’ productions. Perhaps most notable was Parade (1917), commissioned by artistic director Sergei Diaghilev. Picasso’s inclusion in the creative team is somewhat apt – the ballet itself was both whimsical and revolutionary, a vaudevillian concept that saw ‘circus performers’ attempting to lure the public into their curious and metatheatrical sphere. The production was an ostensible move away from the opulence of traditional ballet, alternatively focusing on popular culture. Picasso’s designs were characteristically Cubist; inspired by a marionette theatre in Rome (Teatro dei Piccoli), the stage curtain illustrated a group of performers dining before a show and the backdrops were decidedly distorted. Yet it was possibly the costumes that emblemized the most radical of concepts: constructed with cardboard, angular and imposingly large, the pieces conversely allowed the dancers only minimal movement.

The production suffered an unfortunate and contradictory fate: the choreography panned by critics, it survived for only two performances (later revived in 1920). Picasso’s designs were reportedly applauded for their daring innovation, however, rumours existed that his work was condemned and met with insults, something Diaghilev allegedly encouraged in an effort to further publicity.

Frank Stella on Squash

For some, sport is implemented into our lives out of choice, but for artist Frank Stella it became an enforced regiment caused by a back injury. Not that Stella is complaining – quite the opposite, it seems, as he repurposes his acerbic brushstrokes for the squash court. Celebrated for his minimalist and geometrical abstractions, Stella notes the correlating components of art and sport: ''a painting should move. It is an idealized version of action and gesture […] Squash has that same kind of focusing of energy in the right direction. You get tuned into the action". The match appears fitting: his minimalist approach is exchanged for the crisp white walls and squeaky reverberation of sneakers on lacquered flooring. Yet, Stella’s affection and association with the sport has likewise seen him act as championship promoter and designer of the 2007 Tournament of Champions trophies, his understanding and approach towards both sport and art solidifying their integral and collective natures.

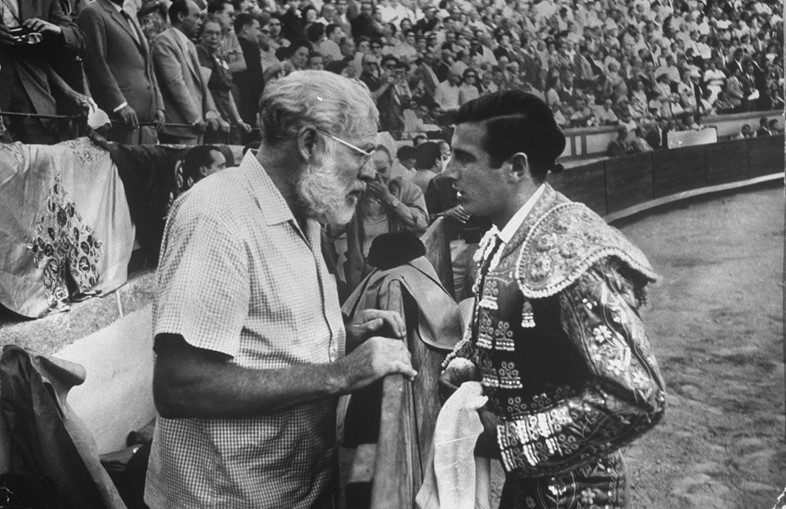

Ernest Hemingway on Bullfighting

Ernest Hemingway has become notorious for his lifelong love affair with bullfighting, controversial though it is; images of his attendance at innumerable events abound, along with his own commentary, and even advice concerning the activity. Author A.E. Hotchner describes Hemingway’s counsel to him (after he drunkenly agreed to a stint in the ring), wherein seemingly only three rules applied: “Number one: Look tragic. Number two: Don’t lean on anything; it’s ugly for the suit. And number three: if the photographers come toward you, put your right foot forward; it’s sexier.”

Hemingway’s authority on bullfighting appears indisputable if one has read his chef d'oeuvre The Sun Also Rises (1926), and later, Death in the Afternoon (1932), his passion and obsession for the sport is evident, arguing that it is a "decadent art in every way", and "if it were permanent it could be one of the major arts".