From a small-scale replica of Villa Malaparte, to the liminal space between hard and soft – meet the furniture designers learning to do more with what we already have

Soft Baroque, a studio for furniture that serves and surpasses its function, was founded in 2013 after co-founders Saša Štucin and Nicholas Gardner graduated from London's Royal College of Art, in Visual Communication and Furniture Design respectively. They describe their work as “future practical... sort of a contradiction. We are interested in modern luxury and inflated versions of reality, but without abandoning consumer logic or pragmatism”. The pair have previously shown at London, Milan and New York design weeks, the Swiss Institute in New York and Christies in London, as well as being designers in residence at Villa Lena in Tuscany, and they are currently developing a commission from Bloomberg, as well as preparing for an upcoming exhibition at Design Miami/Basel. In short, they have a lot going on.

Miniaturisation

Soft Baroque's first collaboration took the form of a miniature of Villa Malaparte, the peach, staircase-dominated house on the island of Capri which played a prominent role in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris. “Our friend was getting married, and we knew she loved the film, and I was really obsessed with the building,” Štucin says, recalling the decision to create a miniature of it as a wedding gift to her. “Nicholas had a studio at the time, and I’d always been obsessed with architecture, but thought it would be too big for me to do. This idea of miniaturisation was so convenient, and [the model] still served a function in the domestic environment – we made it with a marble top and our friend now uses it as a coffee table in her house.”

The idea of recreating buildings or architectural details in miniature has been around since the 1800s, when craftsmen would use the practice to show off their skills in processes such as marquetry. It continues to play a part in Soft Baroque’s work. “We have a few buildings on our list, but we just need to find a purpose,” says Gardner. “We always try to connect the materials with how we produce it, the idea behind it and the function – all of these things need to align. The Villa Malaparte was less aligned because it was just building and furniture, we almost needed another play to make it more of a story that made sense.” But the Villa Malaparte miniature was the project that triggered their working together, and on which they began working out how their backgrounds in graphic design and photography, furniture and architecture could be applied collectively.

Creative Process

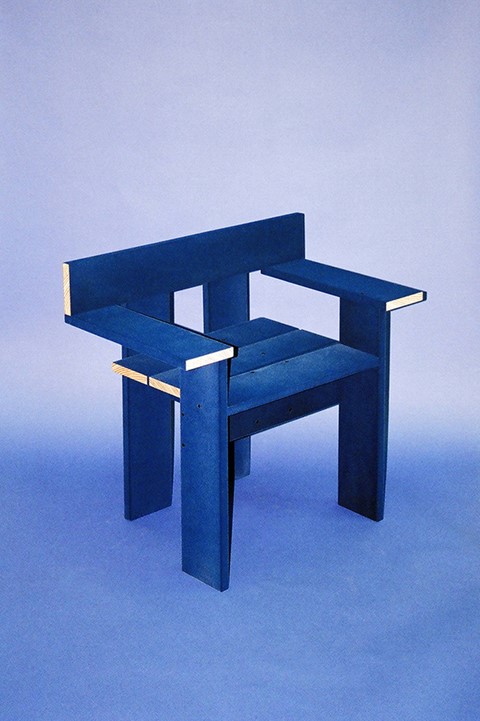

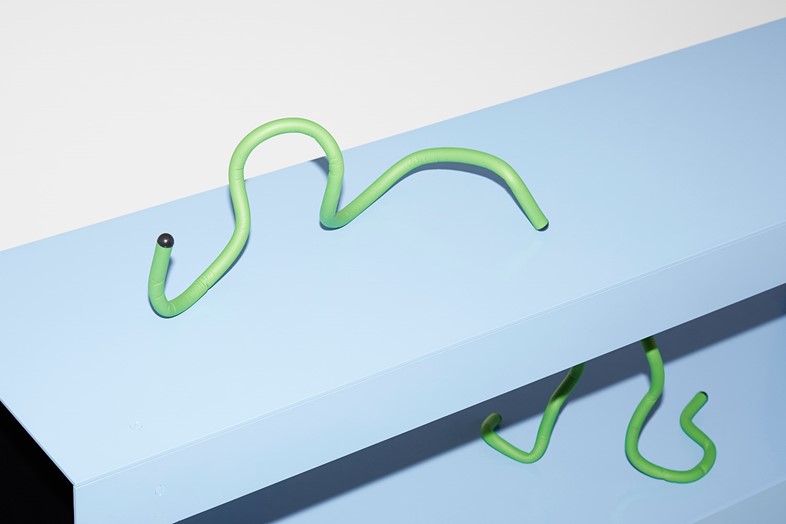

Soft Baroque's work combines materials and forms that already exist, which are then reapplied for more conceptual purposes. “We try to find materials, processes and shapes to fit the idea,” Gardner says. “We like the idea of our objects participating under the same capitalist rules that govern everything else; people buy something because they need the function of it, but they also want to appreciate the aesthetic. Even though our work mostly goes into galleries, we still think about these consumer paradigms as a fake set of rules, in a way. Like designers rather than artists.” This position the pair occupies between art and design, which in itself has become more of a recognised place in recent years, sets up questions about the limitations of each discipline. “In some ways you can get away with so much more in design because the critical level is not as vigorous. But on the other hand, to make something hold together and function can be so much more complex.”

The pair's focus on a level playing field between form and function, process and outcome means that work that they consider to be too indulgent –whether through overwhelming focus on process, or an excess of images – doesn’t really stand up. “I had this problem with graphic design and photography too”, says Štucin, “where I thought, ‘guys, we have too many images anyway, let’s stop. Let’s try to find a way to re-appropriate what already exists, because what’s the point of making more?' It could be seen as negative and non-progressive but I was looking at things and thinking, ‘why can’t we find new ways to use what we have?’”

Design Miami/Basel

Soft Baroque's exhibition at Design Miami/Basel this year is unfurling in collaboration with Copenhagen-based gallery Etage Projects, in its Curio booth. The focus of Curio is on immersive experiences, in which the artist takes care of the whole shape of the space, and Soft Baroque are developing something that will do exactly that. They have been looking into ways to blend the definitions of soft and hard materials. “The materiality of the objects and textiles will be the same. The point is to merge the two,” says Štucin. They will produce a series of furniture and wall pieces made of rosewood veneer, granite and stainless steel – objects that “play with digitising the decorative aspect of a material, and divorcing it a little from its function,” Gardner says. “They will be formal, high-quality pieces of furniture, but distorted, no longer working entirely with the constraints of the physical realm.”

For more on Soft Baroque, see their website.