After her inspired speech at the Parley for the Oceans summit during COP21, we revisit our interview with the brilliant oceanographer from AnOther Magazine A/W11

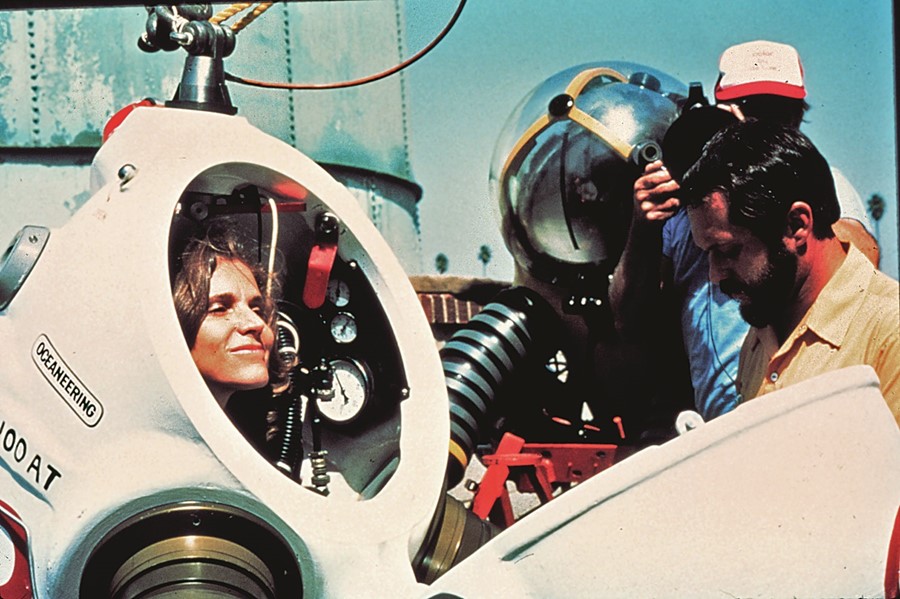

Few people on Earth can tell the kind of stories that Sylvia Earle can. We’re leaning forward intently as the legendary oceanographer recounts one of the most memorable moments of her long career. The year was 1979, and Earle was about to embark on the deepest undersea walk ever attempted. At a depth of 381 metres beneath the surface, she stepped off the edge of a submersible – and into the abyss.

“It was completely dark,” she recalls, “except for the flash, sparkle and glow of the bioluminescent creatures who make their own kind of firefly light. It was like gliding into another galaxy. I touched some of the corals that sprouted from the ocean floor like giant whiskers; they were spiralled like big springs and when I touched them they burst with rings of blue fire. It was just magical and it gave me an appetite for wanting to go deeper and to explore using whatever it took to get me down there.”

Even at 75, Earle exudes a persona that’s half James Bond, half Jacques Cousteau and half Charlie’s Angel – and, the maths add up because she’s already accomplished what one and a half people could hope to in a lifetime: from being named Time Magazine’s first “Hero for the Planet” to being officially classed as a “Living Legend” by America’s Library of Congress. Over a career spanning nearly six decades, she has spent countless hours below the waterline, pioneering early diving suits, living beneath the waves and fighting to protect the vast blue world out there – all while looking very glamorous indeed. It can all be traced back to an early affection for the sea that began long before her groundbreaking venture into the deep, and even before her first scuba dive.

“One of my first memories was hearing the sound of the ocean and then smelling it,” she reminisces, taking us back to her childhood on the Atlantic coast of her native New Jersey. “Soon I could see the ocean through the dunes, and the best part of all was running across the dunes and touching the ocean. I got knocked over by a wave, and my mother saw the expression on my face – at first scared but then realising it was exhilarating and then running back out into the ocean. I’ve been going back ever since.”

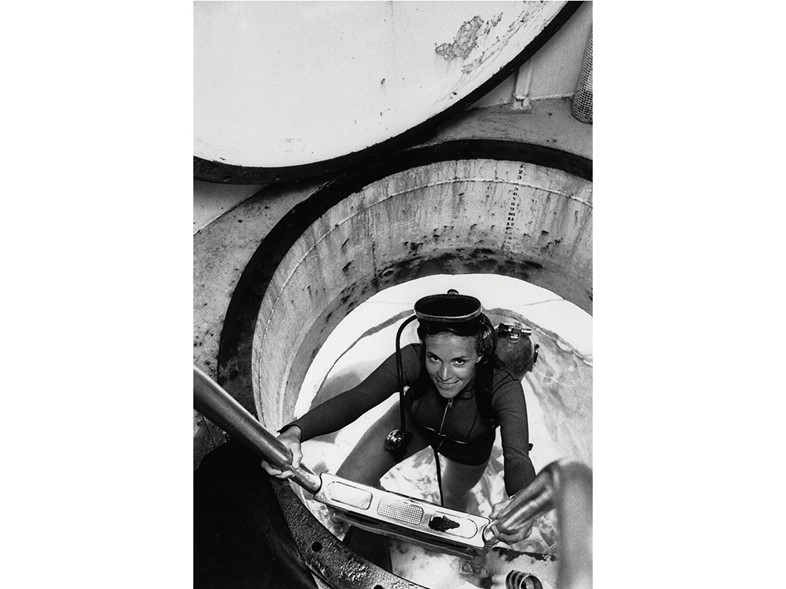

Following this first encounter, Earle – variously called “Doctor” by fellow researchers, “Mom” by her three kids and “Her Deepness” by The New Yorker – set out on a path that would take her to the top of the ocean-going world. After a degree in marine biology which included a memorable introduction to the then-new SCUBA system (“Just breathe normally” was the only guidance she was given) she completed a PhD and a stint at Harvard before eventually becoming chief scientist for America’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In all, she has led more than 60 underwater missions and logged nearly 7,000 hours under the waves – but still remembers her first time. “It was in 1953,” she recalls, losing herself in the moment, “and my first breath was just… it just seemed impossible that you could actually breathe underwater. I knew in my mind that it was possible, but actually experiencing it was such a gulp of joy and I feel it every time I go under the ocean. I love doing it, to be able to feel weightless, to spin on one finger, to do somersaults, to be like a graceful ballerina – even with a huge tank on your back you can do the most extraordinary things.”

"To be able to feel weightless, to spin on one finger, to do somersaults, to be like a graceful ballerina – even with a huge tank on your back you can do the most extraordinary things" – Dr Sylvia Earle

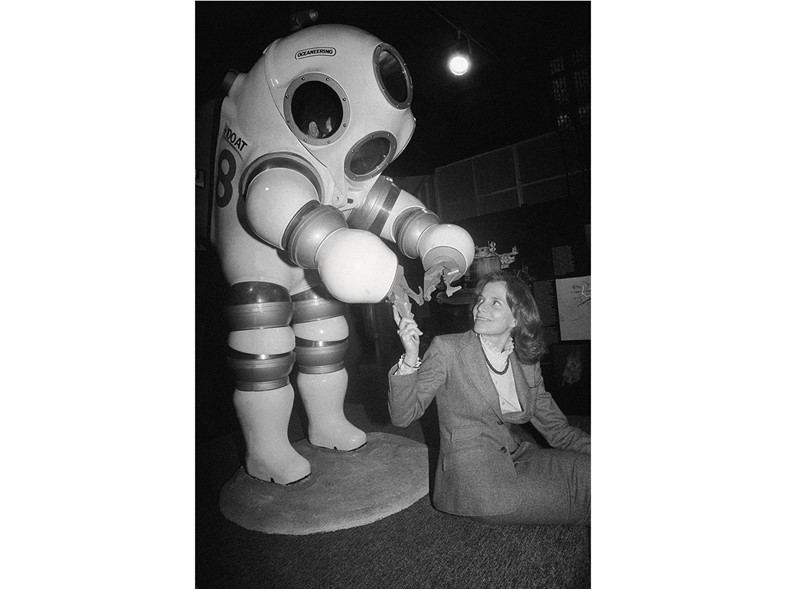

Since then, Earle has gone on to explore deeper and further into the ocean depths – both as a scuba diver and by creating robotic submarines to explore beyond the reaches of humankind. Much of that has been in submarines and diving suits that she and her British-born ex-husband Graham Hawkes designed through their own Steve Zissou-esque outfit, Deep Ocean Engineering.

“We can go down as far as 1,000 metres using subs like Deep Rover,” she explains. “This has allowed us to do 100s of dives in places that had previously not been explored, trying to assemble baseline data in places that had already achieved some form of protection, but also to look at enhanced protection in places that need to be given care.”

As a passionate campaigner, Earle’s main job these days is highlighting the plight of the world’s oceans – but she still manages to get out on (and, of course, under) the water once a month or so. Her record-breaking walk on the seabed remains the deepest-ever dive made by a woman, and Earle’s life work hasn’t just been pioneering in the exploration sense. In 1970 she led the first all-women team to an underwater habitat called Tektite II, located off the Virgin Islands, to demonstrate the use of cutting-edge technology. Nicknamed the “aqua-babes” by the press, Earle and her fellow female pioneers spent two weeks submerged at 50 feet in an inhospitable yet fascinating place – an experience which not only nurtured her growing passion for venturing into the water for the sake of exploration, but also instilled a deep sense of connection with the natural environment.

“I think the most important aspect of living underwater was the gift of time, of being able to stay long enough to get insight into the nature of a place,” she says of her days on Tektite II. “Things that you take for granted on the land, whether it’s going into a forest or climbing a mountain, you cannot do down there. But you can sit there for hours, days, weeks – you get to see the changes over time. One great breakthrough for me came in realising that all fish are different, one from another, and not just the fish, but even the little snails that lived in the vicinity of the lab, you could quickly see that there aren’t any two exactly alike, they behave differently, they look different, they occupy different niches in the structure of the reef. It just hadn’t occurred to me that the diversity of life extends to all life,” she says.

“The other great miracle that also came into focus at that time, is how we’re all connected. Whether you’re a little anemone living in the sand under the sea, a pine tree on top of a mountain or a human being living in a city, we all share the same basic DNA, with infinite complexity and infinite variation that sets us all apart not just as species but as individuals. For me it was just a time to reflect and that’s what has stayed with me ever since: an understanding of how connected all life is and how individual all life is.”

The first-hand realisation of the abundance and complexity of life on Earth became one of the key drives in Earle’s efforts to explore, research and protect the oceans. Today, Earle is enjoying her second decade as an Explorer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society in Washington DC – a coveted position that gives her the chance to reach a wide audience while leading valuable scientific missions.

“It’s a license to play, it’s freedom to explore,” she says in a warm, engaging voice that affirms her ongoing excitement with all things deep. “I have really been given the ability to have a home base at National Geographic with support to take on projects of my choosing, and actually keep choosing to find wet places, and to seek support for these big expeditions. The Sustainable Seas Expedition, for instance, enabled me to explore the coastal waters of the United States and parts of Mexico and Belize. We used some new little submersibles that had just become available – one-person systems that are so easy to drive that even a scientist can do it!”

"Less than 5% of the ocean has been explored, let alone mapped. We have creatures that are just so exotic you look at them and think ‘eat your heart out, Luke Skywalker!’" – Dr Sylvia Earle

Her work with National Geographic and myriad other projects led to an invite in 2009 to accept a TED Prize and make a wish. In a typically enthusiastic exultation she wrote, “I wish you would use all means at your disposal – films! expeditions! the web! more! – to ignite public support for a global network of marine protected areas, Hope Spots large enough to save and restore the ocean, the blue heart of the planet.”

Today, her focus on protecting these key areas (like national parks for the ocean) is chiming with a wider public focus on the importance of the high seas for humankind. From Selfridges’ Project Ocean season to hard-hitting documentaries like End of the Line and The Cove, the plight of the world’s oceans is definitely rising on the global agenda – a welcome development for Earle.

“It’s underway but it’s now time to reach a level of protection that will really secure an enduring place for us within the natural systems that keep us alive,” she pleads. “Only slightly more than 1% of the ocean currently has some form of protection and the part that is safe even for fish and lobster and crabs, oysters and clams and the things we so love to take from the ocean, it’s a tiny fraction of 1%. We have to do much better than this, and I was so pleased to see the UK step up and protect the Chagos Archipelago, currently the largest protected area in the ocean. It’s over 500,000 sq km in the Indian Ocean, where even the fish are safe, and it’s a bold, important move that needs to be used as a source of inspiration for other countries.

“We have a chance, with the Arctic for example, for nations to join together. We have one chance to get it right – we’ve never had access to that frozen ocean before, and now it’s disturbing to hear the interest is more ‘how quickly can we exploit the Arctic?’ instead of saying ‘how quickly can we explore this vast wild part of the planet?’ – that we know has an important role in governing climate, weather and temperature.”

Earle’s global outlook comes from a lifetime spent in the borderless world of the liquid part of our planet – a sentiment often reported by astronauts who return from orbit with fresh insight on the bigger picture. She was actually encouraged to consider a space career when NASA put out a call for female astronauts, but passed up the chance.

“I was honoured to be invited to participate and at least to apply for the space program at that time,” she says diplomatically, “and I was certainly tempted. But at the time in 1970 I had three small children, and the idea of a commitment to really do what it takes – I’m not sure I have what it takes to be an astronaut anyway. Having said that, if there were coral reefs on the moon I’d probably do whatever I could to get there!”

The comparison to the moon’s desolate surface is timely. In a cash-strapped era when her country’s future in outer space is all over the news, she isn’t alone in wanting to explore more of the strange world that lies just beyond our shores. Indeed, even future space airline boss Richard Branson is looking to the depths, with the predictably-named Virgin Oceanic set to use designs based on Earle’s early work to send missions to five deep points over the world’s oceans.

“There’s so much to explore in our part of the solar system – this part of the universe,” urges Earle. “I’m still dazzled by the awareness that less than 5% of the ocean has been explored, let alone mapped. We have creatures that are just so exotic you look at them and think ‘eat your heart out, Luke Skywalker’ – Earth is where the strange and wonderful creatures exist! You don’t have to use your imagination, you can just dive into the sea.”

This article originally appeared in the A/W11 edition of AnOther Magazine.