Gustav Metzger, the art world’s mischievous 89-year-old troublemaker, has been making radical, politically charged work for almost seven decades. When he was arrested and jailed for civil disobedience against nuclear weapons in 1961 alongside Bertrand Russell, he famously told the judge, “I have no other choice than to assert my right to live”. It’s a statement that might define his entire life.

Metzger hasn’t looked back since he fixed a collection of found cardboard boxes onto the wall of a gallery in 1959 and cheekily deemed them art, thereby starting his influential anti-capitalist art movement, auto-destructivism. He went on to create luminous liquid crystal projections and visceral photographic installations of violent acts in history. He has single-mindedly embarked on a one-man art strike to protest commercialisation, and upended 21 trees into concrete in the name of environmentalism – the list goes on.

Just this month, Metzger launched Remember Nature, a global call to action that he spearheaded with the Serpentine Galleries. It launched at Central Saint Martins, with Metzger encouraging hundreds of art students and art professionals to create work addressing extinction, climate change and pollution, all issues close to his heart. “The art, architecture and design world needs to take a stand against the ongoing erasure of species,” he said, adding, “even where there is little chance of ultimate success. It is our privilege and our duty to be at the forefront of the struggle.”

That idealism in the face of despair has marked Metzger’s body of work. After all, perhaps the biggest impetus behind any kind of activism is a refusal to give in to despair or apathy. “As an idealist I have to be optimistic that there is a future, or it just wouldn’t work out at all,” he explains to me, in his east London studio. The titles of his recent exhibitions – We Must Become Idealists or Die at Fundación Jumex in Mexico City, and Act or Perish, the title of a new touring retrospective, currently in Oslo – show that idealism mixed with the utmost urgency has become Metzger’s resounding conviction.

For Metzger, the notion of destruction – cultural, social or environmental – has never been an abstraction. Growing up as a young Jewish boy in Nazi Germany, Metzger’s life and work have been coloured by some of the major crises of our time, from early 20th century fascism and the Cold War’s nuclear threat, through to climate change and species extinction.

He escaped from Germany to England at the age of 12 with his brother. They were two of the 10,000 children rescued by the Kindertransport association in 1939. Their parents died at the hands of the Nazis. Metzger recalls watching the SS marching through his home city of Nuremberg as a child, a memory that continues to haunt his work.

As a teenager in Leeds, Metzger worked as a carpenter and a gardener before joining a left-wing commune in Bristol for a brief period. Then, inspired by a local exhibition of contemporary British art, he met Henry Moore at the National Gallery and asked to become his assistant. Moore persuaded the young Metzger to go to art school instead, and he ended up studying in Cambridge, Oxford, Antwerp, and London, where he studied under the seminal English painter, David Bromberg. After his student days, Metzger continued to paint while working as a labourer on the side, but it wasn’t long until he made a radical break from his contemporaries, abandoning painting to invent auto-destructive art.

The eve of the socially and politically ferment 1960s was an auspicious start for Metzger’s overtly political work. In 1959, in his early 30s at the time, he wrote the auto-destructive art manifesto, launching the influential avant-garde art movement. “Auto-destructive art re-enacts the obsession with destruction, the pummeling to which individuals and masses are subjected,” he wrote. A self-defined Marxist since the age of 16, his distaste for capitalism was clear.

Metzger envisioned auto-destructive art as non-elitist, public art that could last anywhere from a few seconds to 20 years, created using easily accessible everyday materials, like cardboard and industrial products. In his most iconic work, Demonstration at the South Bank, a gas mask-clad Metzger flung acid at sheets of nylon outside London’s South Bank in 1961, reducing the nylon to tatters.

Yoko Ono and members of avant-garde art groups like Fluxus and Viennese Actionism gathered in London in 1966 for the Destruction in Art Symposium, which brought auto-destructive art into the mainstream. Metzger took a leading role in the Symposium, and was fined £100 for organising a “lewd and indecent exhibition” thanks to Austrian artist Hermann Nitschʼs Orgies Mysteries Theater, in which he bathed in the blood of a dead animal. Metzger’s influence continued unabated in the 1960s. His student and friend, Pete Townshend of The Who, smashed his guitar on stage in the name of auto-destructivism, introducing it into the lexicon of popular culture.

Metzger’s ‘auto-creative art’, exists in direct opposition to auto-destructive art, showing that beauty and growth can be created with the technological instruments of our time, not just destruction and violence. The best example is Liquid Crystal Environment – large-scale projections of heat-sensitive liquid crystals that light up in vivid, luminescent patterns. Metzger worked with a Cambridge scientist to make these spectacular, psychedelic light projections in 1965, and they were then used onstage by The Who and Cream in 1966, before being reprised at the Tate in 2005.

While Metzger was making art based on capitalism’s destructive impact on individuals, he was also beginning to investigate industrial society’s catastrophic impact on nature. In 1970, he created Mobile, in which plants were driven around the city housed in a transparent cube on top of a car, hooked up to the exhaust. That informed an ambitious proposal that Metzger devised for the first UN environmental conference in 1972, in which he envisioned 120 cars pumping exhaust fumes into a transparent cube, a work that didn’t come to fruition until 35 years later, at the Sharjah Biennial in the UAE. Considering that our planet may well end up choking on more C02 then it can handle due to climate change in the future, the projects resonate more than ever today. In the early 70s, it was decades before the world would discuss climate change as a serious threat – it wasn’t the first occasion on which Metzger was ahead of his time.

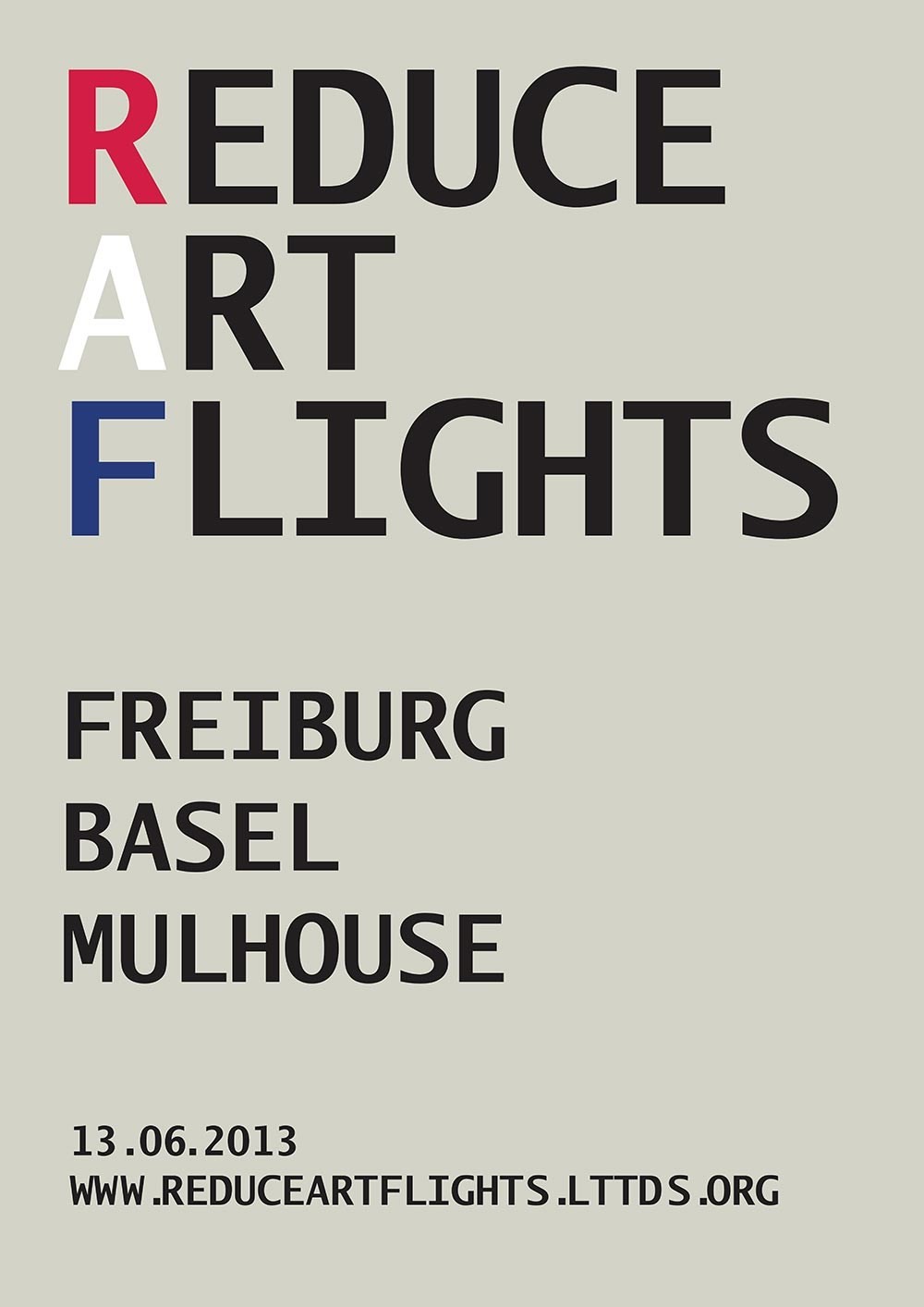

Metzger’s ecological beliefs have continued to come to fore even more in recent years. Along with tirelessly speaking out about species extinction, he started an environmental campaign to reduce flights to art biennales, complete with leaflets and posters. It has been greeted perhaps more with nervous laughter than unanimous enthusiasm from the art-world jet-set, but Metzger has been unfazed by the fact that merging art and activism doesn’t always sit cosily in the hyperluxe world of 21st century globalisation.

In the 2009 public art piece, Flailing Trees, commissioned by Manchester International Festival, the artist created a sculpture of 21 upended willow trees. With the tree tops buried in concrete, the roots helpless above ground, the work evoked the absurdity of what humans are doing to the planet. Art historian, Sir Norman Rosenthal, described Flailing Trees as “a 15th-century Gothic chapel, the trunks standing in for the columns, the upturned roots for the architectural tracery. The image is of a world upside down…”

Last year, Metzger was guest of honour and co-curator, alongside Hans Ulrich Obrist, of the Serpentine Galleries’ Extinction Marathon. The two-day event brought radical environmental consciousness into the inner circle of the art-world. The marathon built on Metzger’s previous work on climate change and extinction – such as, Mass Media: Today and Yesterday, in which he maps species extinction in newspapers in collaboration with gallery visitors, but it also became a call to action for a new generation of artists. It spawned a mass movement to fight extinction, the latest incarnation of which has been Remember Nature. The Extinction Marathon, attended by everyone from Whole Earth Catalogue founder Stewart Brand to model Lily Cole, was dedicated to the pangolin, the world’s most hunted animal. “Gustav told me it is just not enough to talk about climate change, we will never wake up. We have to talk about extinction.” Obrist told The Guardian at the time.

I meet Metzger to speak about a life bringing together activism and art on a bright autumn afternoon in east London. His assistant lets me into his studio, which is in one of Hackney’s indiscriminate new builds. The small figure sitting at a table in the bare bones room, staring ahead and waiting to begin, is Metzger. He is older and frailer than I expected, considering how much he still works, but he is also sharp-eyed, with an intensity that has likely brought him this far. The fact that he’s one of the last of his generation that experienced so much of the 20th century, makes him seem between two worlds. There is a holiness about him that charges the air in the room and induces reverence.

Metzger’s softly accented voice is a reminder of his first 12 years in Germany, he speaks so quietly that you strain to hear his words. Articulate and thoughtful, Metzger punctuates his replies with pauses, some of them long enough to wonder if you’ve asked the wrong question. His bearing and careful, considered phrasing, which doesn’t give much away, evokes a formality reminiscent of another era.

He will turn 90 next year, but his desire to engage with the world’s most pressing problems through art hasn’t waned with age. If anything, it has intensified. “We have the potential now of major, major transformations in understanding our world and in reshaping it,” Metzger points out.

There is an endearing self-effacement, whether Metzger is destroying his own work, consciously stepping out of the limelight, or mobilising, as he has done so often, to start larger movements for change. He says he feels he is simply a small part in a battle that will continue long after we’re all gone.

Here, he talks fervently about the power of idealism in dark times, and about a life in service of the desire to “go beyond”.

Do you feel part of a tradition of artists and other cultural figures engaging with political and environmental issues?

Yes, certainly. Yes, there is an endless flow of people coming and going, who are committed to understanding and changing the way things are done. I see myself simply as part of a stream, a worldwide stream coming and going, through the ages. It’s just a stream, a stream streaming along.

Why did you choose art, rather than say, purely focusing on political activism?

At the age of 17 I visited the Leeds Academy of Music. This was 1943, the middle of the World War, and I had an interview with the director about becoming a composer. He explained that you have to spend years learning about 15 instruments. I thought I could never do this, so I gave up that idea. My next idea was to consider working in social change, as a kind of revolutionary – I lived in a left wing commune in Bristol for six months, and came to realize that that wasn’t what I wanted. I really wanted to be active in art with bits of it being political, and essentially my life has been about art, and the politics came on the side.

"I really wanted to be active in art with bits of it being political, and essentially my life has been about art, and the politics came on the side." Gustav Metzger

Could you tell me how your environmental activism began?

I could tell you almost to the day how it all started. It started in a small town, King’s Lynn where I decided to settle (in the 1950s), I wanted to get away from London, as far as I could. I’d been living in King’s Lynn for some time, and saw a notice inviting people to a public hearing on the future of the North End where I had my house and studio. It was the fishing quarter of King’s Lynn going back centuries. They planned to demolish the entire quarter and replace it with a big road. I instantly decided to oppose this and gathered people to form a society supporting the North End. This was my baptism in activism - we lost the battle and the quarter was destroyed, so this is how it all began.

What do you see as the core problem in the relationship between humans and the natural world?

The main problem is that we think we are on top. We always dominate the natural world and we are determined to go on doing so. The problems are endless and cumulative. We believe that we know everything best. The animal world is endlessly bigger than the human world, and at least as important. The necessity to accept that is perhaps the greatest challenge facing the human world.

And yet, you’re still an idealist?

What is happening in a wider sense of the world is very positive. There’s never ever been so much attention given to these real difficulties. Huge changes are taking place and at the highest level. For example, there’s this immense climate conference in Paris. The more social groupings that unite in the fight for improvement and understanding is for the good. We have the potential now of major, major transformations in understanding our world and in reshaping it. It’s not all doom and gloom by any means, not at all.

"We have the potential now of major, major transformations in understanding our world and in reshaping it." Gustav Metzger

What do you say to young artists and others who feel fearful of climate change and disheartened by the political situation?

I say “Fight, come out fighting”, that’s all I can say. There isn’t much fighting spirit and that’s what is needed, especially from younger people. If we don’t get it, the world is in trouble. There is idealism in this country, it’s not focused, sharpened and applied as it should be. It’s diffuse and incoherent. “We must become idealists or die” – I believe this is the spirit with which to confront our world. It’s the starting point of a critique and of possible organisations. There is not enough idealism involved among young people to deal with the world, and that is required. Without idealism, you don’t have the energy to go forward, it needs to be encouraged, fostered and supported. And it is a fight, this is so important.

Over your lifetime, do you feel that you’ve seen significant change in how humans treat each other and the planet?

Generally speaking, the direction in which we are going is fatal, and needs to be opposed with all possible means. But do I have faith in humanity? If I didn’t, I don’t think we’d be talking here together. I must have faith in humanity, otherwise it just doesn’t come together. The opportunities for the world are immense and as an idealist I have to be optimistic that there is a future, or it just wouldn’t work out at all. I do believe in the future, I must believe in the future. I have to try and do my little bit to try and make the future as intelligent and as reasonable as possible, so I try and do that.

Two simultaneous exhibitions, “Extremes Touch” and “Liquid Crystal Environment” are on at Kunsthall Oslo and Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo, as part of “Act or Perish. Gustav Metzger - a retrospective”, on until January 31, 2016.