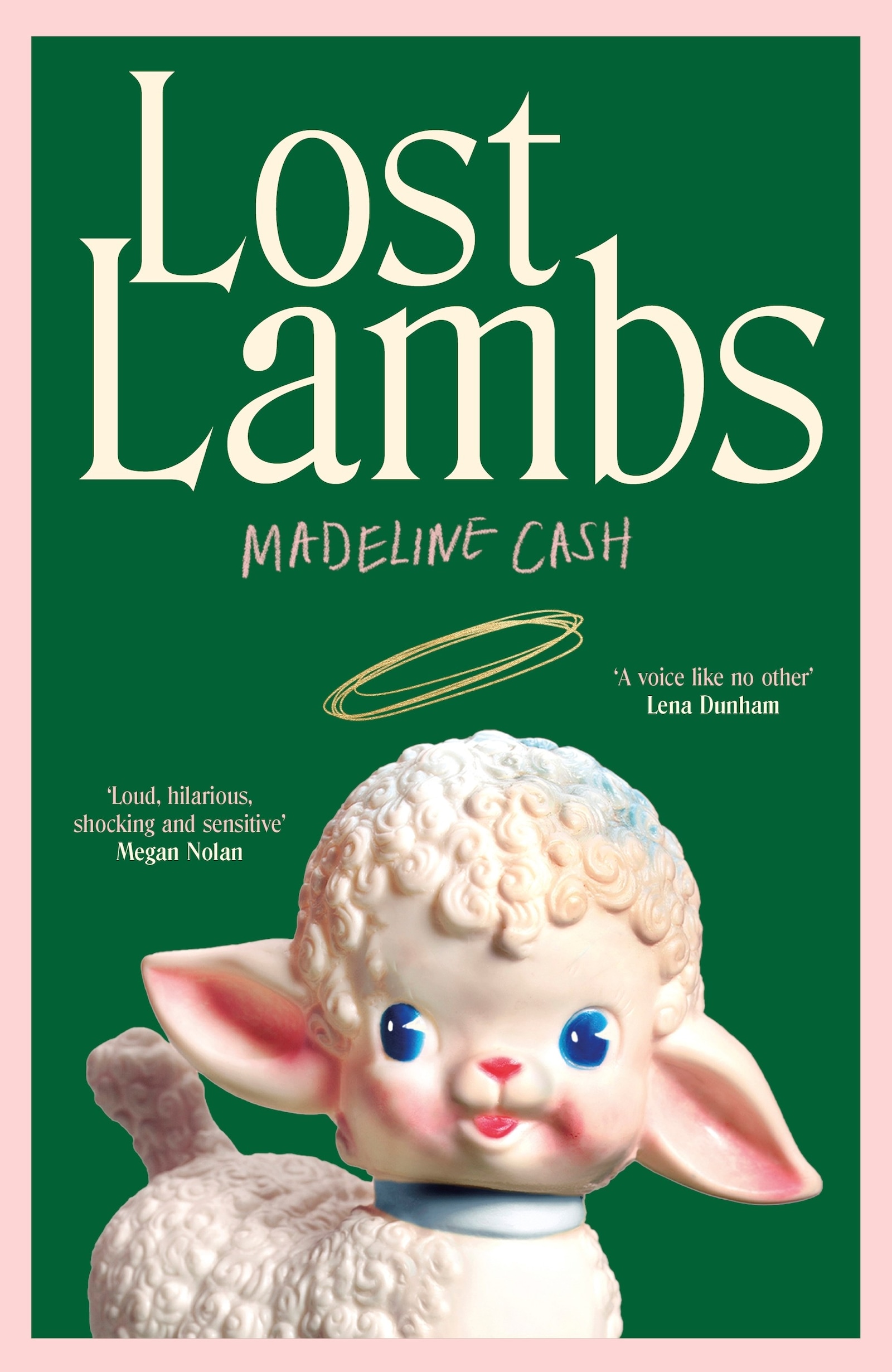

Madeline Cash’s debut novel Lost Lambs is the most successful recent entry into the pantheon of dysfunctional family novels. Tolstoy famously opens Anna Karenina with the truism that “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. The Flynns are certainly uniquely miserable: Bud and Catherine have decided to open up their marriage and the fallout is extreme because nobody is keeping an eye on their three teenage daughters. Harper, the youngest, is a precocious child genius and provides much of the novel’s driving action as her conspiracy theories regarding a nefarious local billionaire turn out to be true. Louise, the middle child, befriends a terrorist in a chatroom and makes bombs in the treehouse, while Abigail, the eldest, is dating a veteran everyone refers to as ‘War Crimes Wes’. No one is happy and everyone is misunderstood.

Cash’s novel has no singular protagonist; instead, we are given an ensemble cast and varying points of view. Lost Lambs is technically ambitious and linguistically playful, but, most strikingly of all, it is a 21st-century novel that is ultimately optimistic. Cash’s characters navigate one another and the novel’s satirical late capitalist world, and are ultimately rewarded with what feels like Cash’s oddest move of all: a genuinely happy ending that feels true. While Lost Lambs is Cash’s debut novel, she has also written Earth Angels, an acclaimed collection of short stories, and she is the founding editor of Forever Magazine.

Here, Madeline Cash talks to AnOther about wordplay, being compared to male artists and her recent move to London.

Marina Scholtz: When I try to explain the plot of your novel, it sounds absolutely wild. A small-town American family is torn apart by an open marriage. Meanwhile, a local billionaire is drinking the blood of teenagers in a quest for eternal youth. Yet, Lost Lambs reads like realist, comic, domestic fiction. What led you to the plot?

Madeline Cash: I wanted to write about community dynamics, and that sort of led me to this family saga. Meanwhile, there were all of these strange billionaires popping up in the American news who were experimenting with life expectancy drugs. I found this fascinating and sinister, and I thought that a character like this makes for a great villain. But a family saga doesn’t typically have a villain, so I had to subvert the genre a little bit and find a way for these two to coalesce and make one cohesive story. The two disparate storylines end up butting against each other, but we probably wouldn’t ordinarily live in tandem with age-defying billionaires.

MS: You’re often compared to Jonathan Franzen, which I think is apt, and the book is often compared to The Royal Tenenbaums. How do you feel about the comparisons?

MC: I think it’s funny that they’re mostly men. It’s a very male-dominated genre, the family saga, the American novel. I haven’t once been compared to Joan Didion or Lorrie Moore. I think it’s nice, and a badge of honour, for work to be read without considering the gender of the author. I didn’t set out to write a ’female’ book or a book with any slant like that. I mean, the comparisons are great. Honestly, I’m like Keith Richards – I’m just happy to be anywhere.

MS: It feels like very good comic writing is increasingly rare. Which funny writers did you look to?

MC: Donald Barthelme’s short stories, particularly The Balloon. I think that the way he takes an absurd story and then subverts the ending and somehow moves you seems impossible. There is this other short story by Daniel Orozco called Orientation that I’m a really big fan of. I think that he stopped writing or died, but it’s the only thing he’s ever written. George Saunders was a big early inspiration. When I was in high school, I honestly loved David Sedaris.

“Honestly, I’m like Keith Richards – I’m just happy to be anywhere” – Madeline Cash

MS: Is there anyone whose tone you wanted to copy?

MC: Everyone that I was reading when I was writing. The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt. I love her. The English Understand Wool is another great one of hers, it’s so funny. Nathan Hill’s new book, Wellness, which also deals with failing – or flailing – marriage.

MS: Lost Lambs is an all-American novel, but you just moved to London. You have such a keen eye for the absurd – what English things have you found the most odd, and do you feel more American for having left?

MC: I didn’t realise that I was such a true blue capitalist, but there you are. I really enjoy having things delivered on the same day; my instant-gratification itch is not being scratched here. What do I find most strange? Everything is strange. I don’t know why people don’t have dryers or air conditioners, but that’s kind of a basic one. Beans should not be eaten with breakfast, or really with any meal if you’re not a cowboy.

MS: I wondered if you talk a little bit about Oulipo and wordplay? The book starts with an infestation of gnats in the local church, and you pepper the word ’gnat’ everywhere where a ’nat’ occurs, as in ’gnaturally.’ This starts by looking like a typo, then the eyes adjust, and then it goes away when the gnat infestation stops. Why the word play?

MC: The Oulipo school just fascinated me. I love the books by those writers: Georges Perec wrote Life: A User’s Manual, which starts by describing every unit in this apartment building, and then you realise while you’re reading it that it’s moving like a game of chess and that it’s almost like a choose your own adventure, but written before that genre existed. I just really loved these playful but formal games that they used in writing. Restraint leads to more creativity. I often found that I would much prefer to have a prompt. In writing school, you usually have to write to some instruction, and I think that is easier. I follow instruction really well, for better or for worse.

“[The book] took a lot of world building, which is why I wanted to infest the text, as well as the town, with gnats. I wanted this feeling that something is not right to be with the reader persistently” – Madeline Cash

MS: Did you set yourself rules?

MC: The initial rule of the book was to not use any proper nouns, so every place in the town and the world is fictionalised. It took a lot of world building, which is why I wanted to infest the text, as well as the town, with gnats. I wanted this feeling that something is not right to be with the reader persistently. It was kind of nutty … People keep thinking the gnats are typos and DMing me to let me know that my book is filled with typos. I probably get three DMs a day.

MS: It does not interfere with the book’s propulsive readability. Was that a goal – entertainment?

MC: Yeah, I wanted it to be. It should be a pleasurable experience. If it ever felt not fun writing it, I felt like it probably wouldn’t be fun to read. I tried to pivot directions or subvert an expectation or hyperbolise the situation. That’s also why the gnats had to be killed – they were tiresome.

Lost Lambs by Madeline Cash is published by Penguin and is out now.