Not long after Toni Morrison died in August 2019, the novelist Elias Rodriques penned an elegy in which he asked: “What will I tell young people – how will I refer to her – who do not know who she is 20, 30, or 40 years from now? We had a Shakespeare, I would like to say. People called her Toni.”

This comparison is not hyperbole or irony: as the Nobel Prize winning author of iconic books like Beloved, The Bluest Eye, and Jazz, Morrison’s oeuvre has a magnitude and depth that few writers have ever touched. Her work has investigated the long afterlife of American slavery, the formation (and deformation) of community and family, and the jagged edges of love and desire with a strangeness and precision entirely her own. Morrison’s novels disturb, provoke, console, and confound: they do not just have impact, they have power.

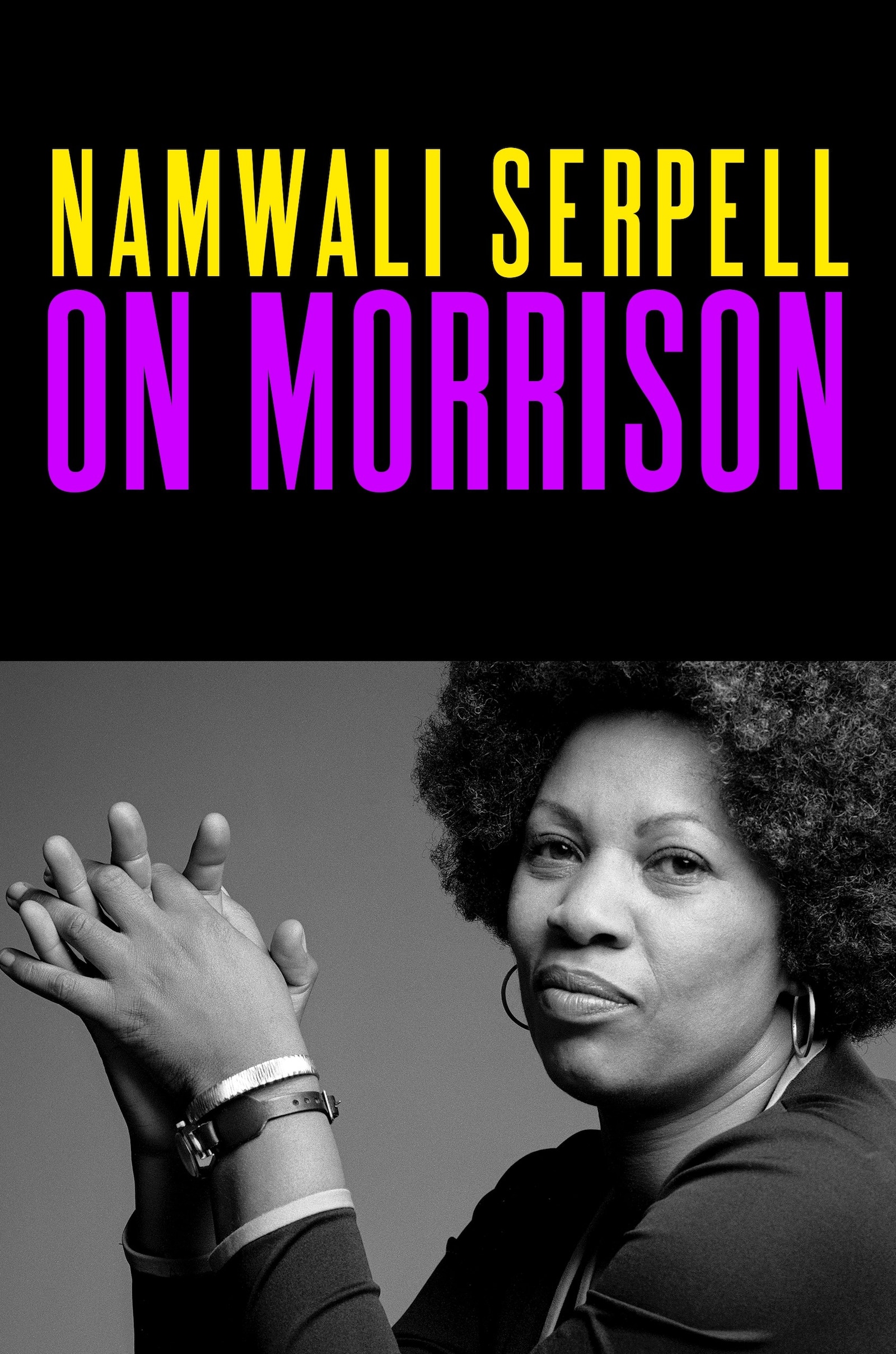

Yet in spite of Morrison’s stature among readers, much of the writing about her work is often wanting: as the critic and academic Namwali Serpell argues in her visionary new book, On Morrison, the great author remains woefully misunderstood, misread and not often met with the depth that her work demands. Instead of reducing Morrison to the tidy formulas and categories into which Black women writers are so often sorted, Serpell embraces the complicatedness and variation of Morrison’s genius, arguing that the difficulty and ambiguity of her texts is, precisely, their point, though not to the extent that they hold readers out. Instead, inspired by those iconic images of Morrison at a disco in 1974, Serpell explains that Morrison invites us into the difficulty, to sweat it out and take pleasure in doing so.

Here, Namwali Serpell discusses her masterful new work of literary criticism, an essential read for all those who have admired the genius of Toni Morrison.

Tia Glista: Can you tell me first about your own formative encounters with Morrison’s writing?

Namwali Serpell: Maybe the best story is of me reading Sula. I had read and studied some of Morrison’s other works in college, but it was when I was housesitting for my graduate advisor when I was a PhD student in my twenties, one lazy summer here in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I noticed a copy of Sula on her bookshelf. It was the wonderful 1970s cover with the Afro woman with the yellow flower, and I just loved it. One of the things that I love about being someone who comes to the [literary] canon from elsewhere – growing up in Zambia, coming to America – you learn things about the American canon, but you always have an openness to new works of literature. So I just opened it and read it in one sitting.

By the end, as is the case for many people, I found myself just weeping. It was such an exquisite experience of grief and love and resonance. It really pierced something in my heart, whereas my readings of her other novels had been much more cerebral, even more spiritual. This book was really my love, and I didn’t want to reread it for a long time; I like to preserve that experience, to read books sometimes without a pencil in my hand.

TG: You have all of these incredible close readings of Morrison’s novels, but your own insights are also interspersed with details from her archive, including some details not previously known by the public. How did you undertake this archival work, and what was it like to be amid such precious pieces of the past?

NS: We should keep in mind that she was very careful to separate Toni Morrison, the author, from Chloe Wofford, which is her birth name. She liked to think of them as two very separate beings. So the archives are really the archives of Toni Morrison, with some measure of connection to Chloe. What it comes down to is a picture of the author as she comes into being. What it created, for me, was what I would call more of a literary relationship, a kind of connection via reading, rather than a personal relationship. Even when you’re reading her journal entries, many of which include notes for the novels, it feels more like you’re eavesdropping in a conversation she’s having with herself, rather than having a conversation with her.

I never met Toni Morrison personally, and I think there’s something really precious about having a relationship to another person that is mediated entirely through language and art. Language, for Morrison, was essential to how she understood human beings and human relations. She says in her Nobel Prize speech, “We’re human. We do language.” I love “do language.”

“I never met Toni Morrison personally, and I think there’s something really precious about having a relationship to another person that is mediated entirely through language and art” – Namwali Serpell

TG: You quote Morrison’s claim that “the structure [of her work] is the argument”, and this becomes a guiding principle for thinking about how it is her use of aesthetics, arguably more than content, that offers the most profound insights about race, gender, sexuality, family, community, ideology, et cetera. For those who haven’t read the book, can you elaborate on this position and why it is so central to On Morrison?

NS: I can give one example, which is her novel Jazz. It would be really hard to say what the message or the single upshot of that narrative might be. One of the things that Morrison does is she takes the events and she treats them like she can riff on them, she can mix them up, she can tell them out of order. What she’s looking at is how events chime together, or how events can go back and repeat, how they can create a kind of leitmotif or a pattern that re-emerges, right? So she’s actually using the book as a manifestation of jazz itself: the book does not include the word jazz, it doesn’t actually refer to any specific jazz musicians, she said the book is not about jazz. The book is jazz.

We’re all familiar with the idea that jazz is all about riffs, or that improvisatory quality where you’re kind of making it up in a live performance. One of the things Morrison does is she allows the narrator of the book to stumble as they riff and progress, to get things wrong and to correct. For Morrison, jazz and improvisation includes in it this ability to fail, to briefly stumble. But what matters is what you do with that, how that then becomes another path or another riff that you can follow. So you have her articulating a theory of how we deal with failure, with stumbling, with making a mistake, with error, all within the structure of the novel.

TG: The emphasis on form, you show, also complicates a sometimes superficial politics of ’representation’ to which her novels might be reduced. Why do we need to encourage readers to pay more attention to form – and how might this be enabled?

NS: It’s really important to think of the attention to form as something you can do in the second read, or retrospectively. One way to think about it is like when you walk into a building for the first time, like the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and it’s got the spiral frame that makes you walk in a circle upwards: you experience what that feels like as the light is pouring in, the way that you look at the paintings, the motion of travelling up, right? You experience it. But it’s only when you’re leaving that you look at the building and you see what it is that you just experienced.

Having a hyper awareness of form as you’re reading is not what any writer wants. No writer wants you to be like, “Oh, that’s a metaphor.” They want the metaphor to make your brain explode, or, as Emily Dickinson said, to take the top of your head off. Morrison is one of the authors who most begs for re-reading. The structure of the novels produces a kind of desire to continue to debate and interpret what happened; Morrison never wanted you to close the book and be done. In this way, she connected her work to African folktales and Greek tragedy, which are all about community storytelling, and staging really intractable, important, knotty, binds that don’t have easy solutions. She wants to lay out the problems and have us talk about them, not provide a single message or a single flag or slogan.

“Having a hyper awareness of form as you’re reading is not what any writer wants. No writer wants you to be like, ‘Oh, that’s a metaphor.’ They want the metaphor to make your brain explode” – Namwali Serpell

TG: To that end, the other thing that becomes a kind of spine for this book is an insistence on the deliberate difficulty of Morrison’s writing, which other critics might try to get around. Why is this such a vital quality to preserve?

NS: We live in a world right now where I think people associate confusion, ambiguity and muddledness with the kind of propagandistic hypocrisy and deceit that characterises fascism. But it seems to me that instead of pretending that the way to counter that is by adhering to a rigid notion of certainty, truth and clarity, that actually, we would do better to understand how uncertainty works, how ambiguity works, how confusion works, and what it can do for us that’s positive.

How can it shake up some of our calcified beliefs about how things should work? Something that I learned in writing this book and in teaching and re-reading Morrison’s work is that she never stayed still. Every novel is different. She changed her political positions several times. She did not feel like consistency was something to hold on to. What you want to do is have integrity, and part of that integrity is always a form of self-doubt, self-questioning, and allowing other people also to interrupt your self-conception and to make you think again.

One of my favourite structural things she does in one of her late novels, Home, is that she’ll have a narrator tell a sequence of events, and then in the next chapter, the character will speak to the narrator and say, ’That’s all wrong. Everything you just said didn’t happen that way.’ What an incredible humility to be able to write these beautiful sentences and then have the character you’ve created undermine them. It’s a remarkable way to view the world, but it’s also a remarkable model for us about how to maintain integrity, precisely by allowing yourself to be open to change.

On Morrison by Namwali Serpell is published by Penguin and is out now.