As David Foster Wallace’s magnum opus turns 30, Sam Moore reflects on the book’s cultural impact and its uncanny prophecies for 21st century life

Infinite Jest is probably a novel that more people have heard of than have actually read. The 1,000 page-plus opus – that oscillates between a tennis academy, a halfway house, and the hunt for a lethally entertaining videotape, all with a dizzying number of footnotes for good measure – has, in the three decades since it was first published, become something of a meme; a shorthand for the kind of book that everybody talks about and that nobody has read. It cast a vast shadow over its writer, and over decades of literary fiction.

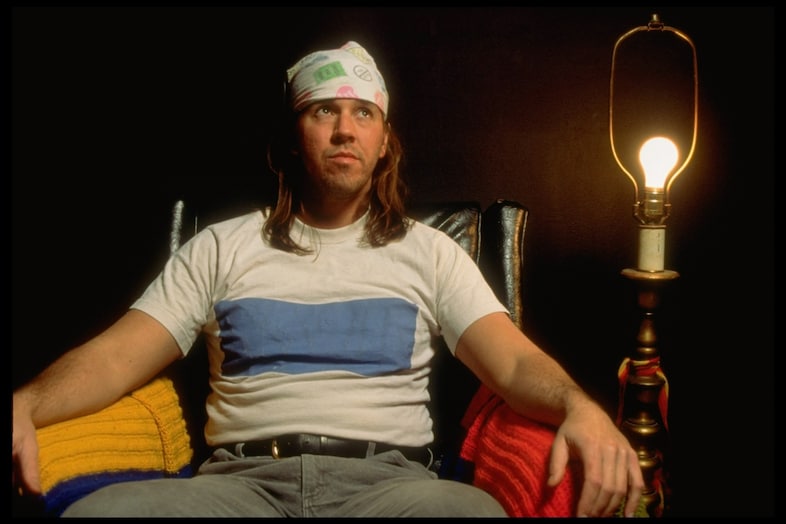

David Foster Wallace often feels like a difficult man to talk about; in the years since his death, more details have emerged about the violence he was capable of inflicting on those closest to him. Wallace was a man who wrote obsessively about his obsessions, whether in short stories like The Depressed Person, or his final novel, the posthumous and unfinished The Pale King, about boredom and beauty for characters working for the IRS in Peoria, Illinois in 1985 (the book even contains experimental cameo by the man himself in the fourth-wall-breaking, tongue-in-cheek Author’s Foreword – a foreword that doesn’t appear until over 60 pages into the book). And then there’s his non-fiction – often lighter than the novels – where he wrote with immense detail and wonder about cruise ships, tennis, dictionaries, and David Lynch. But, looming over all of it is Infinite Jest, a book that is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this week.

When it comes to Infinite Jest, the most tempting thing to do is talk about all of the things that Wallace was able to accurately predict about the 21st century. Through Videophonic technology, the InterLace media system, and subsidised time (in which corporations can buy a year in the calendar; much of the novel takes place in the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment) capture how it feels to live in the 21st century. And the eponymous film – dubbed ‘The Entertainment’ by characters – something so entertaining that viewers have no choice but to watch it eternally until they die, feels analogous to doomscrolling. But to talk about the book as merely a prophecy of what the world would become does a disservice to the real, beating heart of the novel; that it somehow manages to teach us what it means not just to live in this world, but survive it.

At its core, Infinite Jest is a book about addiction. In one memorable scene, a character describes his father’s obsession with watching reruns of the sitcom M*A*S*H, until “he was no longer able to converse or communicate about any topic without bringing it back to the program.” The novel is full of characters who are or have been addicted to seemingly every vice under the sun. And at first, its tempting to think of the act of reading Infinite Jest itself as a kind of addiction; its sheer length and the intensity with which it throws facts, figures, and seductive substances of the reader certainly does a lot to place them in a similar position to Wallace’s cast of characters who are, more than anything else, trying to fill an existential void in themselves. And reading Infinite Jest does feel like it casts a spell. But in the same way that treating the book as nothing more than a catalogue of technological and psychological prophecies undermines it, so too does thinking of it as a book that simply mirrors the idea of addiction.

Instead, what Wallace created is a book that offers itself as a remedy to addiction. More than just a warning about the way technology and pleasure would come to evolve – the book is full of jokes about jerking off, and Wallace himself mentions in a book-length interview with David Lipsky that “it’s gonna get easier and more convenient and more pleasurable to be alone with images on a screen” – Infinite Jest offers a roadmap to try and understand this version of the world, and even try to come out of it in something close to one piece. Wallace wrote with and about patience, about the importance of paying attention. In one of the novel’s tennis-focused sections, he writes that “how promising you are as a Student of the Game is a function of what you can pay attention to without running away.”

And there are lots of times when, reading Infinite Jest, it can be tempting to run away – its sheer length, the need to flick between the narrative and the encyclopedic endnotes, its bursts of horror and violence. The novel’s fatally addictive Entertainment – and the many forms it seems to have taken through 21st century technology – are what Wallace spends over 1,000 pages not just warning readers against, but teaching them to overcome it. When Wallace introduces Ennet House, the state-funded halfway house and rehab centre that is the novel’s heart – where the tennis academy is its brain – he writes that if one found themselves there, they might learn that “no single, individual moment is and of itself unendurable.” Infinite Jest teaches this through a succession of what seem like unbearable moments, stitching them together by demanding patience and care from the reader in a world that increasingly wants to offer the opposite.

Infinite Jest (30th Anniversary Edition) by David Foster Wallace is published by Back Bay Books and is out now.