As a new season at Barbican launches, we present picks from an unfathomably rich – and highly censored – period in Iranian filmmaking

Hear the term “new wave cinema” and a particular kind of film likely comes to mind: French, black-and-white, frenetically edited. Yet while the French New Wave was defining European cinema in the 1960s and 70s, a different wave was taking over filmmaking practices halfway across the world. The Iranian New Wave also emerged in the 60s and was the first major filmmaking movement to come out of Iran: although a cinematic tradition had existed since the early 20th century, strict censorship and limited resources meant that the national cinema before this period was largely popular, low-budget fare. With the filmmakers of the New Wave, however, creative, aesthetic and narrative experiments were developed that continue to be felt in contemporary Iranian cinema: an emphasis on allegorical storytelling as a means of making commentary that bypasses censorship laws; an emphasis on women, children and working-class stories that give voice to oppressed minorities; and, of course, a legacy of censorship that has made many of these films impossible to watch in post-revolution Iran.

Curated by Ehsan Khoshbakht, a filmmaker and director of Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna’s film festival dedicated to retrospective cinema, Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave is a season of films held at the Barbican in London dedicated to restoring, rediscovering and reframing some of the classics of this period. With works by seminal directors such as Abbas Kiarostami and Ebrahim Golestan, the season offers a rare glimpse into a culturally immense yet historically erased period in cinematic history. Here, we pick out some of the highlights from the season.

A Wedding Suit (1976)

A decade after his death, Abbas Kiarostami remains one of Iran’s most famous and influential directors. His films were essential in establishing the Iranian New Wave, pioneering devices that would go on to become extremely familiar – allegorical storytelling, everyday realism, the exploration of children’s interior lives – in Iran’s contemporary cinema. In this, his third feature film, three young boys – two tailors’ assistants and a waiter – hatch a plan to experience a brief moment of luxury by covertly “borrowing” a fancy suit the night before its wealthy owner is due to collect it. Kiarostami transforms this small moment of adolescent subterfuge into both farce and thriller, the setting of the shopping centre turning into a Rear Window-esque Panopticon as the boys scurry through to get both jacket and trousers on the hanger in time. Made three years before the revolution, the incendiary state of Iran’s class politics are writ large; the suit is a cipher for social and economic hierarchies that must be traversed but never overtly broken.

The Ballad of Tara (1979)

Playwright and filmmaker Bahram Beyzai is perhaps best known for his film Bashu, the Little Stranger, considered one of the best Iranian films ever made. In this lesser-known early work, Beyzai draws on his career-long fascination with Persian folklore and myth to create a fantastical tale of female desire and agency. Tara, a young and beautiful widow, returns with her children to her family home to find her grandfather has died and left her his belongings. Shortly afterwards, the ghost of an ancient warrior begins to haunt her, claiming he cannot rest until the sword left in her grandfather’s possession is restored to him, only to fall deeply in love with Tara herself. Here, Beyzai’s filmmaking interrogates the meeting point between tradition and innovation, using the familiar model of Shia passion plays to tell a story of female sexual autonomy. Released in the year of the revolution, the film has been banned in Iran ever since.

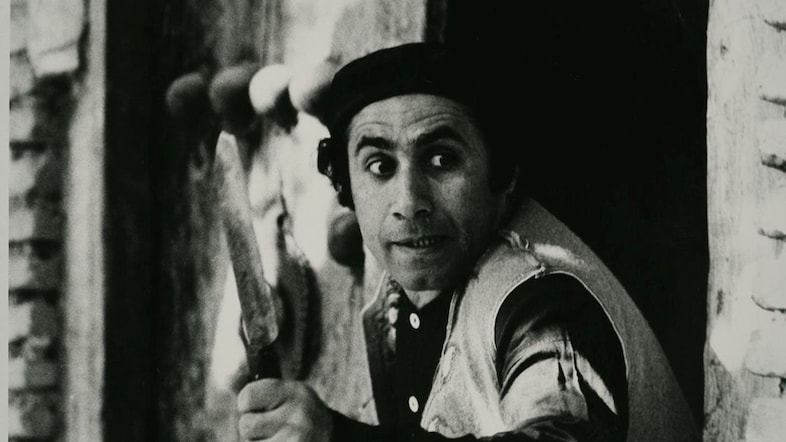

Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure (1974)

Ebrahim Golestan’s Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure has been cloaked in controversy since its brief release in 1974 (it was banned in Iran two weeks after it first showed). A weird and wonderful satirical tale, the film follows a poor farmer who discovers a chamber filled with treasure beneath his field and transforms into a tyrannical despot overnight. Upon release, it was seen immediately as a commentary on the corruption of the shah’s regime and their extraction of Iran’s oil resources for their own ends, and consequently banned. Yet like the best political satire, Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure is as funny as it is damning, documenting the increasingly chaotic antics of its protagonist with a Safdie-esque glee. In Golestan’s hands, wealth becomes a means towards indignity and stupidity, as the poor farmer acquires ever more possessions and loses everything else. It turned out to be the last film Golestan ever made.

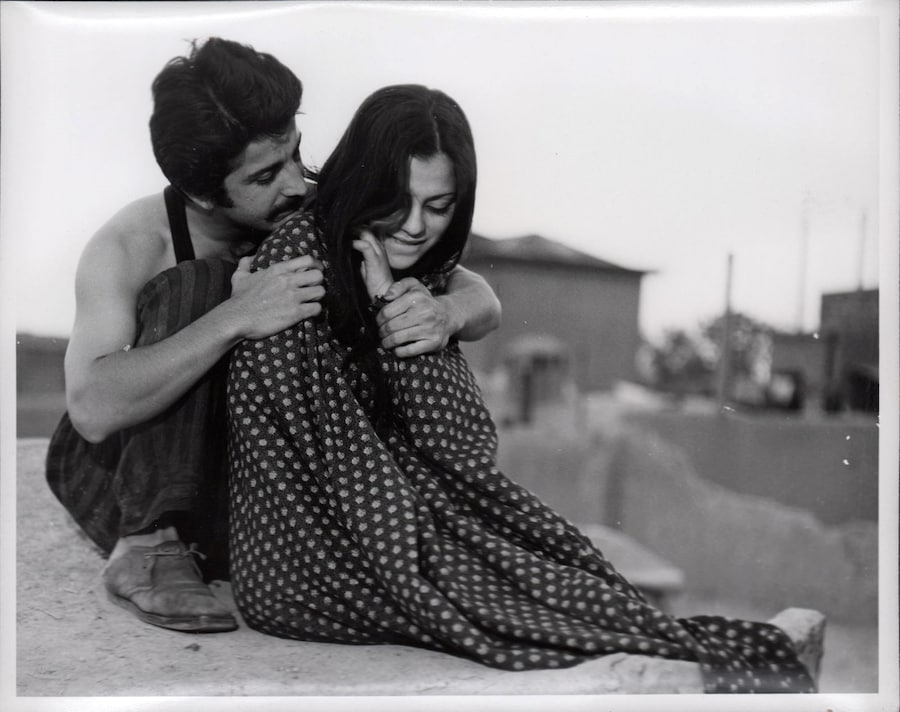

The Carriage Driver (1971)

For a film about two love stories, Nosrat Karimi’s The Carriage Driver begins – quite unexpectedly – with a funeral. Zinat’s husband and Morteza’s father has died, leaving Zinat a widow and the young Morteza as man of the family, with all the authority that living in Iran’s patriarchal society implies. When Zinat rekindles a former connection with a carriage-cum-taxi driver, Morteza is reluctant to give his blessing, but his refusal is complicated by the fact he’s in love with the carriage driver’s daughter. Iran’s complex sexual politics set the scene for a farce of entangled family dynamics in this shining example of Iranian popular comedy. It is not difficult to see why this film was also banned in Iran following the revolution: Karimi exposes the absurdity of female virtue and male dominance by subverting the typical generational power balance, moving away from traditional conservative ideologies of marriage and towards a freer imagination of desire and care.

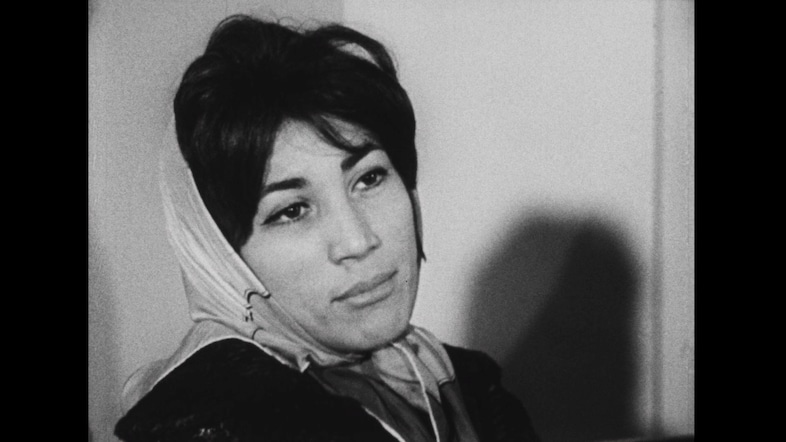

Courtship (1961)

Iran’s complex courtship dynamics are also placed front and centre in this short film by Ebrahim Golestan, part of a Canadian anthology film exploring marital rituals in four different countries. Golestan approaches the subject with delicate intimacy, carefully observing the conversation, gestures and anxieties that make up traditional Iranian courtship, in which a groom’s female relatives politely petition the father of the potential bride for a union between the families. Golestan’s gentle staging of these ceremonies stands in quite funny contrast to the English-language commentary imposed on the film by its Canadian producers, but this anthropological veneer aside, Golestan’s short captures the rich tradition of Iranian society at the time, including an appearance by seminal poet and filmmaker (and Golestan’s partner) Forough Farrokhzad.

Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave is at the Barbican in London until February 26.