One Saturday afternoon back in 2014, Tash Walker was midway through a shift at Switchboard, the UK’s national LGBTQIA+ support line, when their curiosity was piqued. Taking a break from answering calls, Walker wriggled into a crawlspace above the common room that was being used as a makeshift storage area. Here, Walker discovered the charity’s log books: pages and pages of call records written up by volunteers between 1975 and 2003. Collectively, they offered an evocative snapshot of LGBTQIA+ life in the UK during decades of great progress and seismic trauma: from the gay liberation movement of the 1970s to the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, and onto halting steps forward for trans and gender-nonconforming people in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Though there’s something romantic about the way Walker stumbled on this queer treasure trove, the fact that it was stashed away also feels telling. Queer history isn’t handed to us at school like stories of wars, kings and queens. Generally, we have to seek it out for ourselves. “When I started reading the log books and reaching out to past Switchboard volunteers, [former volunteer] Lisa Power said to me: ‘Tash, there’s a PhD in the project you’re embarking on,’” Walker recalls with a laugh. Power was absolutely correct, but Walker decided to disseminate the contents in a more accessible way. Together with fellow writer and podcaster Adam Zmith, they launched The Log Books, an informative and profoundly moving podcast that recently launched its fourth series. Now comes The Log Books: Voices of Queer Britain and the Helpline that Listened, a 400-page deep dive into our collective queer history. In a way, Walker and Zmith are taking us into that crawlspace with them, and shining a torch over the log books’ unseen stories.

Like the podcast, the book uses selected log entries, which were written down swiftly and succinctly while volunteers were on shift, as a jumping off-point to explore fascinating corners of our recent queer history. A chapter about the LGBTQIA+ community’s past persecution by the police begins with an entry from May 1988 about a gay sauna in south London being raided. “About 50 police entered premises at 8pm-ish and carted out most of the customers,” the log book notes. Walker and Zmith include first-person accounts from former Switchboard volunteers, longtime survivors of HIV/AIDS, and queer elders who created radical ways of living outside of the heteronormative family unit. They also offer personal reflections on how their own lives were shaped by Section 28, a cruel, ambiguous and confused piece of legislation that prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities. Enacted in 1988 and finally repealed in 2003, it effectively meant that the teachers who helped to mould a generation weren’t allowed to mention that queer people even exist.

Working on the book proved transformative for both of its authors. “I found this process to be a complete unravelling of self. I went to a very raw place where I realised that a lot of what has fuelled me in life is anger,” Walker says. As a teenager, when Walker turned to teachers for support in processing their queerness, they were sharply shut down. “But with that anger, there’s an element of forgiveness. All of us were victims of an oppressive state-wide system,” they add sanguinely. Zmith says the project has helped him to comprehend “the weight I was carrying around as a queer person growing up in the 90s and 00s in a homophobic household”. Both he and Walker also found the project nurturing because it contextualised their own places in a community rooted in struggle and mutual support. “It really helped me to understand my relation to the world as a queer person. I learned that my sense of duty shifted away from my parents and towards the LGBTQIA+ community,” Zmith says. “I feel so indebted to our queer elders, but it’s not really debt. It’s more of a bond.”

“[Making this], we’ve learned so much about what we’ve been through as a queer community and how resilient we are. Progress isn’t linear, but it does move forward” – Tash Walker

The Log Books will encourage a similar sense of reflection and connection in readers. Walker and Zmith’s extensive research uncovers queer stories that are rarely told – for instance, the courageous lesbian mothers who had to ‘out’ themselves at custody hearings in the 80s – while charting changing social attitudes. Log book entries reveal that Switchboard volunteers were always kind and empathetic to trans callers, even if the terminology they used to refer to them is now incredibly dated. However, Walker points out that behind the scenes, Switchboard was riven with the same “internal transphobia” that has infected many LGBTQIA+ organisations. When Diana James became the charity’s first trans volunteer in 1987, several incumbent female volunteers quit on the spot. It’s a chilling echo of the way trans people are treated today by some bigoted members of the queer community.

Switchboard’s role has evolved over the years. When the internet became widely available in the late 90s, it no longer needed to provide information about all facets of LGBTQ+ life, from gay bars to healthcare. But in 2026, two years after celebrating its 50th anniversary, its core purpose remains constant: to listen to queer people who need to be heard. Walker and Zmith hope their book adds to this proud tradition. “We’re listening to people from different generations, which is especially important at this moment in time,” Zmith says. “From working on The Log Books, we’ve learned so much about what we’ve been through as a queer community and how resilient we are,” Walker adds. “Progress isn’t linear, but it does move forward. When we come together and push against a united enemy, we’ve proven time and time again that we can resist.”

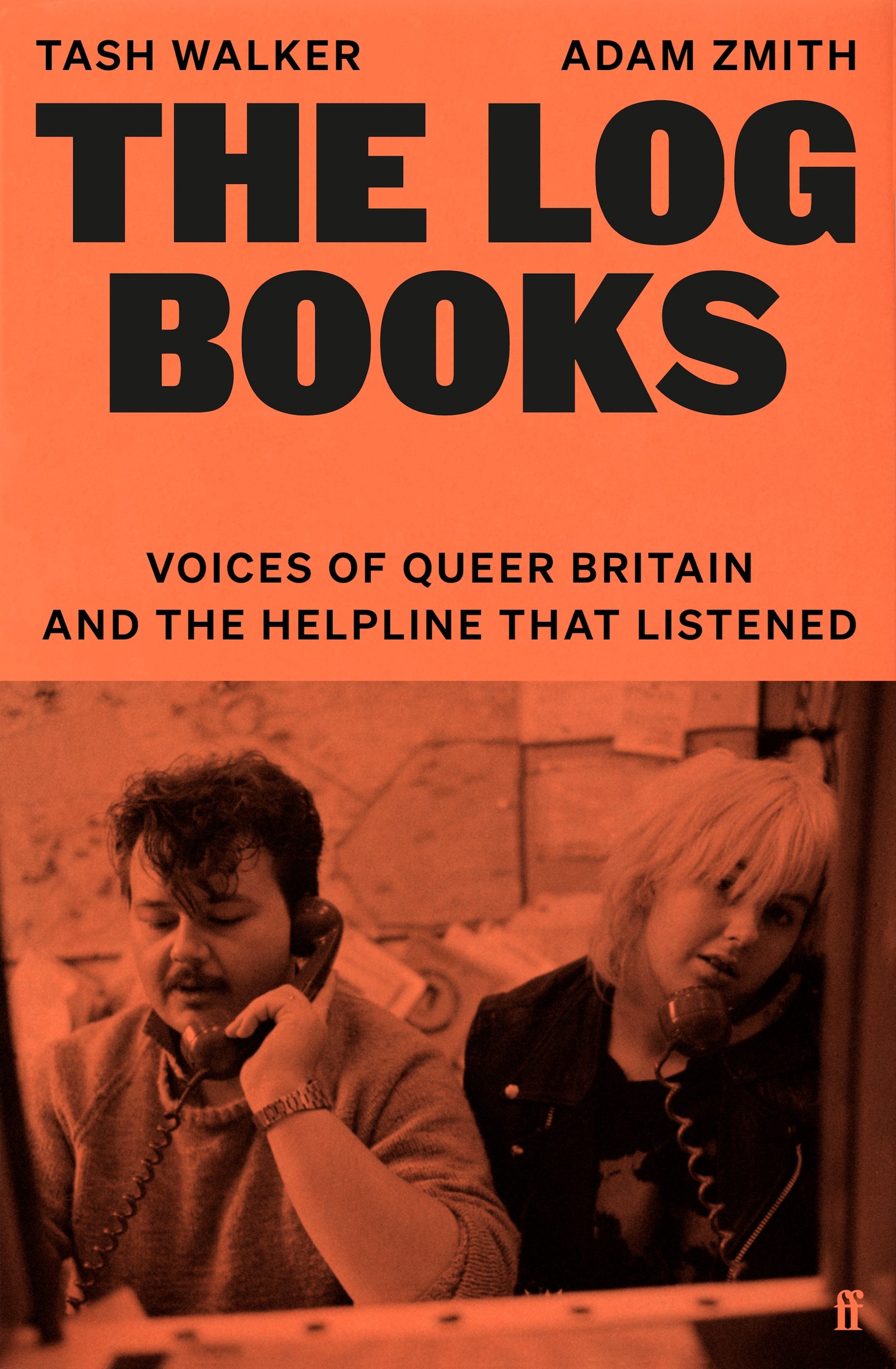

The Log Books: Voices of Queer Britain and the Helpline that Listened by Tash Walker and Adam Zmith is published by Faber & Faber and is out now.