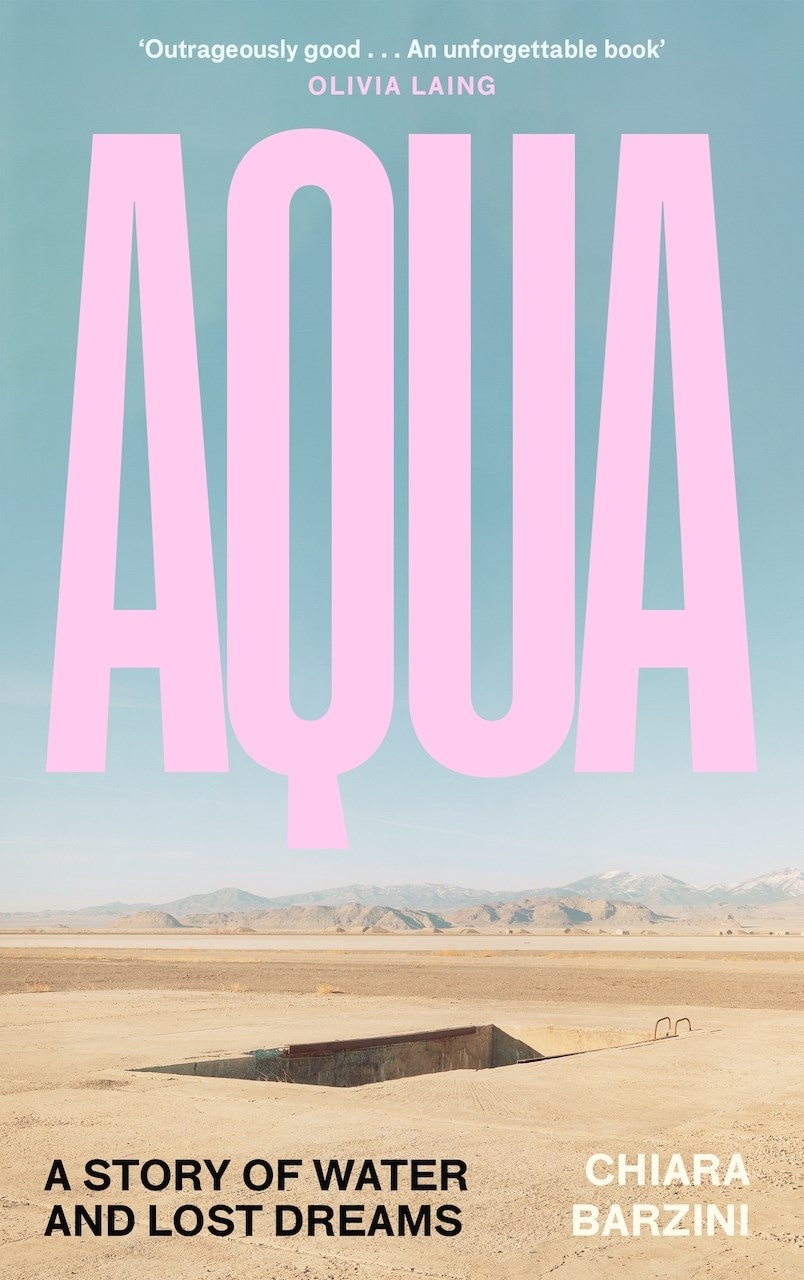

A few years ago, a friend gifted me a manual on the construction of the Los Angeles aqueduct written by William Mulholland, the founder of the city as we know it today. I was inspired by those pages to follow the path of California’s water, to write my book, Aqua, and take this series of photographs. These are images that speak of the end of water, of unbridled dreams and illusions of abundance. A reckoning with the catastrophic decline of the American empire.

During the trip, I made a pilgrimage to the environmental disaster of the Salton Sea and to the artworks of the Bombay Beach community, a trip that brought me into the orbit of renegade artists and philosophers, people who have turned the desert’s emptiness into an experiment in art, community and survival. The silence and emptiness of the place became a presence of their own. One morning, walking along the shores, I felt the pebbles under my feet ... or so I thought. My companion laughed and told me the sand was not made of stones but of crushed fish bones, the residue of mass die-offs brought on by years of drought. That fragile mixture of beauty and desolation became the pulse of the journey.

I got in a car with my two best friends and retraced the path of water to try to understand the most elusive and mysterious part of the city of Angeles, but also of myself. I met holy visionaries in the Mojave Desert – among them Sister Paula Acuña, a one-eyed mystic living in the outskirts (though everything is an “outskirt” in the Mojave) of California City who experienced Marian apparitions of the Madonna of Guadalupe. She blessed me with a poster of a flying Mary and warned, “You’re going to need this.” She was absolutely right.

California City itself is the city that never was, an unlucky twin sister of Los Angeles that fell prey to real estate marketing schemes and became the site of the state’s great disappointments and swindles. It is useless land sold to hopeful immigrants whose American home dreams went to waste, a place that promised water it never had to begin with. I was fascinated by the aerial images of Noritaka Minami, the great photographer who revealed California City’s urban-planning madness to museum goers and thinkers around the world.

I discovered the ruins of the Japanese American concentration camp of Manzanar from the second world war, a place of unbearable beauty and sorrow. Beneath the Sierras, I walked among the remains of barracks and gardens that internees had once tended in an effort to bring dignity to their lives. At the heart of the site rises the white obelisk known as the Tower of Sorrow, inscribed with the characters “to console the souls of the dead”. Nearby stands a small Zen garden, serene and haunting, and beyond it, a baseball field where Japanese Americans, imprisoned without trial, were forced to play and perform patriotic pageants to prove their allegiance to the very government that had detained them. Today, Manzanar is somehow designated as a national historic park, a surreal transformation that encapsulates both the remembrance and a kind of denial that California history does so well.

“These are images that speak of the end of water, of unbridled dreams and illusions of abundance. A reckoning with the catastrophic decline of the American empire” – Chiara Barzini

We drove to Owens Lake, once a bright alpine reservoir, now a mirage of almost completely dried-up water at the foot of the Sierras, and visited the Alabama Spillgates, where water once flowed luxuriantly in the last century. Now only a trickle remains. The gates themselves were often bombed in acts of rebellion by local dissidents, farmers and ranchers who felt robbed of their water rights and blamed Los Angeles for stealing what had once sustained their land and their lives.

In Los Angeles, I had the honour of sitting down with Robert Towne, the screenwriter of Chinatown, a film whose story forms a kind of mythic backdrop to my book Aqua. It was his last live interview. His daughter Chiara, who has since become a dear friend, likes to joke that the only reason her father let me into the house was because we share the same name.

I also tried to look at the brighter side of this apocalyptic story. I visited the 2000-year-old Roman Aqueduct at Ponte Lupo to find a sense of continuity rather than an epilogue. These images tell of mourning for the end of an era that always seemed invincible to us, but they are not without hope. The history of California, that of ancient Rome, of the communities of the desert and the Sierras are a vehicle for exploring the kaleidoscopic spaces of a collective unconscious that sounds the alarm of the apocalypse but fights it at the same time.

Aqua by Chiara Barzini is published by Canongate and is out now. Chiara Barzini’s photos are on display at Dorothy Circus Gallery, London.