Friendships are like romances – sprawling, intimate, devoted. “[They have] a definite sense of aliveness,” writes Andrew O’Hagan. In his new book, On Friendship, the author of Caledonian Road reminisces about the bonds that have shaped his life. Across eight essays, O’Hagan moves through laughter, loyalty and loss, charting the curious business of growing older while trying, and sometimes failing, to hold on to the people that once defined us.

Too young to have seen the moon landing but old enough to witness the “technological wonderment” that followed, O’Hagan recalls fondly the futuristic melodies of Ziggy Stardust, the appearance of new wave group Tubeway Army on Top of the Pops as they sang Are “Friends” Electric? in 1979, and being chosen for computer club in 1983 – only now recognising these moments as premonitory of the world to come. “Faster, more accessible, more democratic, the internet was a parenting device that felt like a pal,” he writes. “Soon, the hallmarks of friendship – proximity, shared knowledge, secret history – would be embedded in the machines themselves.”

But for all its promise, O’Hagan warns of the digital drift – the quiet substitution of real touch for digital tether. “Maybe it’s worth pausing, with each digital step, to ask if the thing that is swiftly and magically being replaced is not worth protecting. Friendship is one of these.” He wonders whether “friending” constitutes commitment, or if we can truly swear loyalty to someone whose voice we’ve never heard, whose name might be invented. The questions are pressing, even as he acknowledges the joy and optimism of the internet – its capacity for connection, curiosity and community-mindedness.

O’Hagan’s world is dotted with extraordinary friendships: Edna O’Brien, Seamus Heaney, Christopher Hitchens, members of The Stone Roses, and Colm Tóibín, to whom the book is dedicated. Put stardom aside, and what emerges is a portrait of ordinary, tangible, human intimacy.

He remembers the first moments of friendships formed, hooting with laughter as a boy, the sense of time being on your side, and the comfort of people who “could offer happy answers to ridiculous doubts about the future.” He tells us of good company, of dinner parties, trips to the pub, and conversations in the corner cafe. Through music, poetry and memory, he examines friendship as a lifelong act of refinement and calls on the necessity of bringing people, shared moments and touch back into view. On Friendship is part love letter, part lament, and a stark reminder of what makes us human.

On a dark autumn’s evening in his lamp-lit studio on Primrose Hill, Andrew O’Hagan discusses the internet, ‘friending’, and how friendship is the ultimate form of resistance to the straying pull of self-sufficiency.

Rose Dodd: I’d like to talk to you about the chapter ‘friending’, in which you discuss the dawn of the internet and its effect on friendship. How have you witnessed friendship evolve in this time?

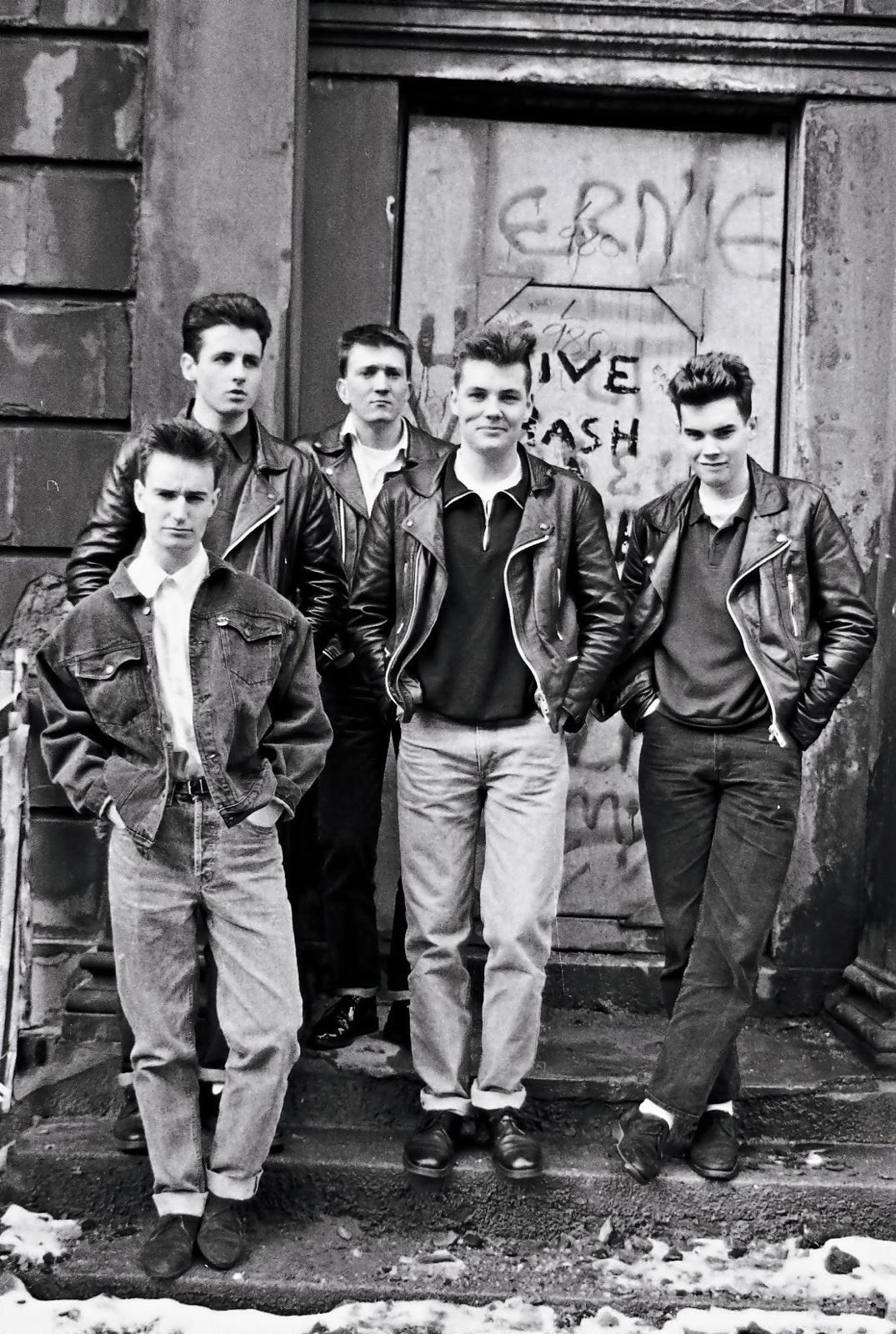

Andrew O’Hagan: I was really into the American novelist Jack Kerouac when I was a teenager. I wanted to talk to other people who liked Kerouac. There was this little fanzine, The Kerouac Collection, published in Leeds. I wrote to them and they wrote back. I went to the post office, put my letter in an envelope and sent it to these guys, who sent things back and introduced me to other guys who were into Kerouac. We started writing to each other, and created this little group where we’d talk about our love for The Dharma Bums or The Subterraneans, On the Road. It took us months and months to find this community. Nowadays, there would be a chat room for that – it would come up on your screen in about four seconds, and in six, you’d be talking.

RD: Suddenly you can connect with people not just quickly but all over the world.

AOH: I could be speaking to people who like Jack Kerouac in China or St Petersburg. Friendship has become something that’s potentially global because of the internet, and that’s great. But with this globality came an alienation effect.

RD: Not how it was first pitched.

AOH: All those Mark Zuckerberg types, the Silicon Valley boys of the late 90s and early noughties, they spoke as if it was this great communication tool that would make the world work, that would make the world friendly, connected.

RD: ’Connected’ – a buzzword. The connectivity boom.

AOH: I remember when ‘friending’ became a verb. It was all about connection but what it’s actually done is disconnected people from personal realities.

RD: I remember signing up for Facebook. Suddenly how many ‘friends’ you had, which included people you’d never met, became a measure of your popularity.

AOH: It’s a fantasy that the internet promotes. Before, you made friends in real life – if you were lucky – and you held on to them. People think that they have hundreds of friends because they’ve got followers on Instagram. The idea that your personal army are your friends – it’s fantasy.

“People think that they have hundreds of friends because they’ve got followers on Instagram” – Andrew O’Hagan

RD: We’re talking about phones here – not just the internet – which have also changed the nature of friendship.

AOH: I’m a middle-aged guy and I pick up my phone today, without thinking about it, four or five times an hour. Sometimes it’s in my hand constantly. It’s an extension of my body. In a very real sense, it’s a brain at the end of my hand. And over the course of the day, I rely on it, not only for communication in what is now an old-fashioned sense, but for self-awareness – for maps, banking, checking the weather, looking at my appointments, photographing friends, checking my heart rate.

I used to make a date down the landline. I would dial the number and say, “Fancy a drink later?” “Yeah, great.” “I’ll meet you in the pub at half seven,” then you’d put the phone down and there’d be no way of communicating. If the bus broke down, there was no way of warning – you were physically cut off from them. Now, when you’re not physically here, I still know where you are. We’re over in touch with our friends. We no longer have to wait for the gratification of seeing somebody. I wonder if a little bit of distance isn’t quite good for friendship, just as it is for other forms of love.

RD: I feel the wrath of uncertainty in friendships. And our connectivity makes for novel concerns like jealousy or FOMO.

AOH: The possibility of misunderstanding is heightened. Before, the clandestine life was very possible. You could go out with friends and not invite others but now on social media everyone sees everything. I actually lost a friend over this once. He cancelled on me – which is fine, I’m easy to cancel because I don’t mind. I understand the concept of the better offer, but he didn’t tell me and I saw him dancing at somebody’s birthday party on Instagram. It was the lie that was upsetting.

RD: The truth always comes out. What do you think this kind of ultra-connectivity – with friends and at once information – says about our nature?

AOH: There’s a promiscuity to online life. It takes accountability and personality out of the picture too much. People can say things under assumed names, they can hide behind masks. You can live a sort of ghost life. And that to me is anti-friendship.

“We’re over in touch with our friends … I wonder if a little bit of distance isn’t quite good for friendship, just as it is for other forms of love” – Andrew O’Hagan

RD: And anti-responsibility.

AOH: People are graffiting on a wall and then disappearing, saying things they’d never say in real life. Similarly, people in cars might stick their fingers up at people. You’d never do that if you bumped into each other on the street. Human beings seek spaces where they can behave unnaturally, where we can exercise our id. The internet is the ultimate vehicle for that. Yes, there’s joy on the internet, lots of splendid, beautiful, interesting, community-minded behaviour – but it is also a super highway of id. That’s to say, people who are so into their own one rubric, their own headline, utterly devoted to one single defining idea, that they will obliterate anybody who doesn’t agree with them without any space for listening.

The internet has the power to draw us into intolerant places where we think we can shout oaths and hateful statements as if into the void, only here’s the problem: it’s not a void, and these statements are landing on people’s phones and in people’s heads and they’re shaping and sustaining ideas.

RD: Do you think there should be some censorship or policing?

AOH: Look, I’m a big movie fan. And I think it’s probably right that young people who may have bad dreams don’t watch a movie with sexual violence and murder. That’s not censorship, that’s certification. With a tweet, you can take out opinions, opponents, ways of life, cultures, at a distance with telescopic sights. You can hurt people from a distance. That’s a breakdown in human communication. Where the internet was invented as the ultimate sublime virtuous communication tool, it ends up a weapon that creates mayhem.

RD: The question of freedom of speech comes up naturally.

AOH: But it’s an exercise of freedom of speech as a way of silencing other people’s freedom of speech.

RD: Do you think friendship is a remedy to this? Is that what your book is?

AOH: That little book is a sweet little call to arms, a reminder to reach out. From the minute we’re born, we’re on our own in this world, from beginning to end, which sounds like a gloomy thing to say, but it’s not because one of the first things babies do is put their arms out, and that is joyous. I don’t think I’d be here without my friends.

RD: What is good friendship then?

AOH: It’s an act of endless refinement, of reaching out, of deepening connections, until the day you die.

“Believing that a virtual reality, something artificial, can offer us friendship is a huge risk. Friendship is flesh and blood” – Andrew O’Hagan

RD: What is the best piece of advice a friend has ever given you?

AOH: The genius editor of the London Review of Books, who was at first my employer but quickly became a friend, once said to me about someone: “They believe too much in what they believe. They think too much like they think.” It’s a paradox, of course, but it comes down to truth and searching for the truth and trusting that the truth may not be in line with what you at first believed or thought.

RD: As you said, you lost a friend not over them cancelling on you but because they didn’t tell you why. Is falsity the enemy of friendship?

AOH: Believing that a virtual reality, something artificial, can offer us friendship is a huge risk. Friendship is flesh and blood. It’s organisms existing at the same time. It’s the simultaneity of it that really matters for me. Once you take reality out of it, we become lonely. We go back to that position of not having true human connection. Technology pushes us in the direction of being able to do more and more without each other, towards total self-sufficiency. We don’t need to be in an office. We don’t need to go to the restaurant. We don’t need friends in front of us. We don’t have to share anything with anybody. It’s the cult of solitude.

RD: You and your machine.

AOH: If I’m smoking a cigarette, I want someone to smoke the other half. Everything’s better if you’re doing it with someone nice. Because the machine is a piece of artificial brilliance but it’s still only a machine – it turns off. And when you turn it off, it feels nothing back.

On Friendship by Andrew O’Hagan is published by Faber & Faber and is out now.